“Golightly? Fuck Golightly,” Natasha Lyonne’s Nadia Vulvokov spits, standing in a library and rifling through the g’s. Anybody who mistook her character in season 1 of Russian Doll—with her lost cat, her love of nightlife, and her tireless conviction that to belong to another human being was a fate far worse than death—for a millennial update on Capote’s flighty, frothy Breakfast at Tiffany’s heroine ought to interpret this as a sly correction. Nadia, who does not go lightly anywhere, is and always has been an entirely new creation, a foulmouthed and hedonistic wit with the delivery of a 60-year-old chain-smoker.

The show’s first season, which saw Nadia dying on the eve of her thirty-sixth birthday party and then finding herself looped into an endless cycle of rebirth and death, doomed to live the same 24 hours until she reached a necessary personal epiphany, was a bold and unusual piece of work. If it was yet another comedy about trauma, it was also a comedy about quantum physics—a curious exploration of the possibility of life in other time lines that was not exactly scientific, not exactly spiritual, but somewhere in between the two. Nadia was a sybarite who seemed poised to tip over into genuine addiction. Her many deaths reflected her own death drive; they were also a visualization of the very relatable feeling of being thirtysomething and perpetually circling one or another of life’s drains in a large city. Russian Doll, in other words, felt like a very funny, allegorical horror story in which the big jump scare was being a geriatric millennial with no plans, no prospects, and a less-than-spotless lifestyle. Who among us hasn’t woken up one morning and, tongue furred and temples pounding, momentarily wondered if he or she had actually died?

Russian Doll’s new season is, both temporally and conceptually, more difficult to explain clearly than the last; since I’m also loath to spoil it, I will preserve as much of its mystery as possible by saying very little about what actually happens. As far as its concept goes, it is a sort of time-traveling detective story, and its format allows Lyonne to reveal her character’s real antecedents, the most obvious of whom seems to me to be the shambling, dry, perpetually easygoing P.I. Philip Marlowe in 1973’s The Long Goodbye. Like Elliott Gould in that picture, Lyonne’s Nadia moves through life as if at a perpetual incline, terminally laid back, the cigarette dangling from her lips occasionally jerking upward to register either cool surprise or cool amusement. “I gotta take a leak,” she growls, stopping a hookup short. “My bladder’s really fuckin’ my dick tonight.”

Just as Marlowe lurched from one unsavory scene to another, barely breaking a sweat even when being roughed up by toughs, Nadia takes an extraordinary number of bizarre and logically impossible developments in stride. In the first episode alone, she is sent back in time to 1982 by a New York subway train, pops a Quaalude, meets and almost sleeps with a mysterious, greasy man, robs her grandmother, learns an explosive secret about the inheritance she mentioned losing in the previous season, and eventually catches sight of herself in a mirror to discover that she is not Nadia at all.

Natasha Lyonne has often seemed to be the result of a freaky body swap, as if a young woman from New York and, say, Peter Falk or Al Pacino had been hit by lighting simultaneously in 1973. A hilarious, sexy redhead with a 40-a-day voice and a history of addiction and arrests, she is in effect the White Lodge Lindsay Lohan, albeit five or six years older and a little closer to a female wiseguy than a broad. Sober since 2006, she is a poster girl for successful recovery but has not lost her edge—in an interview with New York magazine in 2019, she professed to being attracted to “a sort of male, ’70s typology, that kind of genderless sort of person,” and the disparity between her small, feminine form and this innate, out-of-time tough guy, eh? demeanor is the key to her appeal as a performer.

When Lyonne first created Nadia Vulvokov, it was a reaction to what she perceived as the industry’s inability to realize for her the specific kind of characters she wanted to embody: wounded chancers with smart mouths, the kind of people who were doomed to be ancillary characters as women but were allowed to sit front and center as men. Nadia’s tics and mannerisms are her author’s tics and mannerisms; ditto her heritage, mommy issues, former problems with addiction, and personal style. “To be clear, when I say sane,” she stresses to a shrink this season, “I mean eccentric, but, you know, lucid—it’s kind of my defining characteristic. Think good cop, crazy cop.”

It makes sense, then, that as Natasha Lyonne gained more control over season 2 of Russian Doll, having taken over from the writer and director Leslye Headland as showrunner, it would become a little more eccentric, too. Balancing Netflix legibility with brainy cool, it plays both sides by invoking classic cinema or quantum theory or philosophy, and poking fun at itself for its highbrow aspirations at the same time. (Having one’s cake and eating it is, I assume, an easier feat when there are an infinite number of simultaneous time lines.) In a television shop, when an employee proudly informs Nadia that as well as selling televisions he is “the assistant editor of a zine about commodity fetishism and the Debordian spectacle,” Nadia replies speedily, with a shrug: “Alright, well, we live and we die, huh?” It’s a funny bit of hand-waving from Lyonne, and it’s also an informative character note for Nadia, who has tasted death over and over and can see no point in philosophizing in the face of its inevitable arrival.

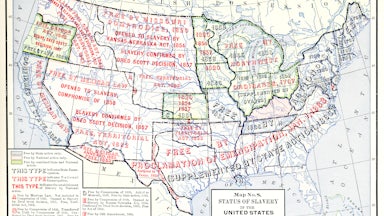

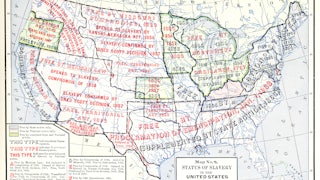

If the first season of Russian Doll had its own through lines about inherited trauma, the new season makes them a pervasive A-plot, the terrible engine of its shaggy and inventive story, which unfurls across the decades in order to take in Nadia’s—and by proxy, Lyonne’s— Jewish heritage, as well as her grandmother’s experiences in Hungary in World War II. “You’re not a creationist, are you?” a character asks Nadia at one point. “Ah,” she replies, a little wistfully, “wouldn’t it be nice to have someone to blame?” What the exchange made me think of was the Jewish joke about a concentration camp prisoner who meets God in heaven and then cracks a joke about the Holocaust. “That isn’t funny,” God chastises, and the man says, ruefully, “I guess you had to be there.” Whatever is cracking Nadia’s world open and sending her hurtling back into the past, forcing her to experience firsthand the pain she has inherited by birth, it is not God; the funniest joke in the entire season is a fuck-marry-kill riff on the age-old conundrum of going back in time and killing Adolf Hitler, but even minor changes Nadia makes to the history of her family do not stick the way she hopes.

Lyonne suggested in an interview with The New Yorker that she is prepared for Russian Doll to lose some of its earlier fandom with this series—for those who are tuning in for one more dose of madcap time-fuckery in contemporary New York to be turned off by a seven-hour exegesis on the immovable weight of human history, and the way that trauma trickles down through generations like hot blood. As in Michaela Coel’s equally autofictional I May Destroy You, which began as an unflinching exploration of the fallout from a date rape and unraveled—brilliantly, singularly—into a fragmented, quasi-Lynchian redemption narrative, the show still carefully replicates the nonlinear, loopy thinking that can result from addiction or abuse. Last time around, though, its internal logic with regard to Nadia’s temporal funny business was clear cut enough to warrant an approving piece in The New Scientist. Now less is explained and more is felt, as if Lyonne is reaching deep into her skull and pulling out great gloopy handfuls of her brain for our amusement, scrambled and a little gory and occasionally hard to look at.

It is this increased emotional involvement that, I think, makes this season of the show a triumph, an improvement on the original series because it is darker, wider in its scope, and generally more: more honest, more experimental, more reflective of its maker. Nadia’s laid-back cool has never felt like a more perfect foil for the magnitude of every situation she is put in, her easy rasp a metronome that keeps a lazy, groovy time even when everything around her is dissolving. She observes the degradation of her world, the shifting tide of history threatening to drag her under, and says, lightly, Well, we live and we die, huh? Wouldn’t it be nice to have someone to blame? Yes, says Russian Doll, but seeing as we don’t, maybe we should just get on with it. Survival! What a concept!