The young woman who narrates

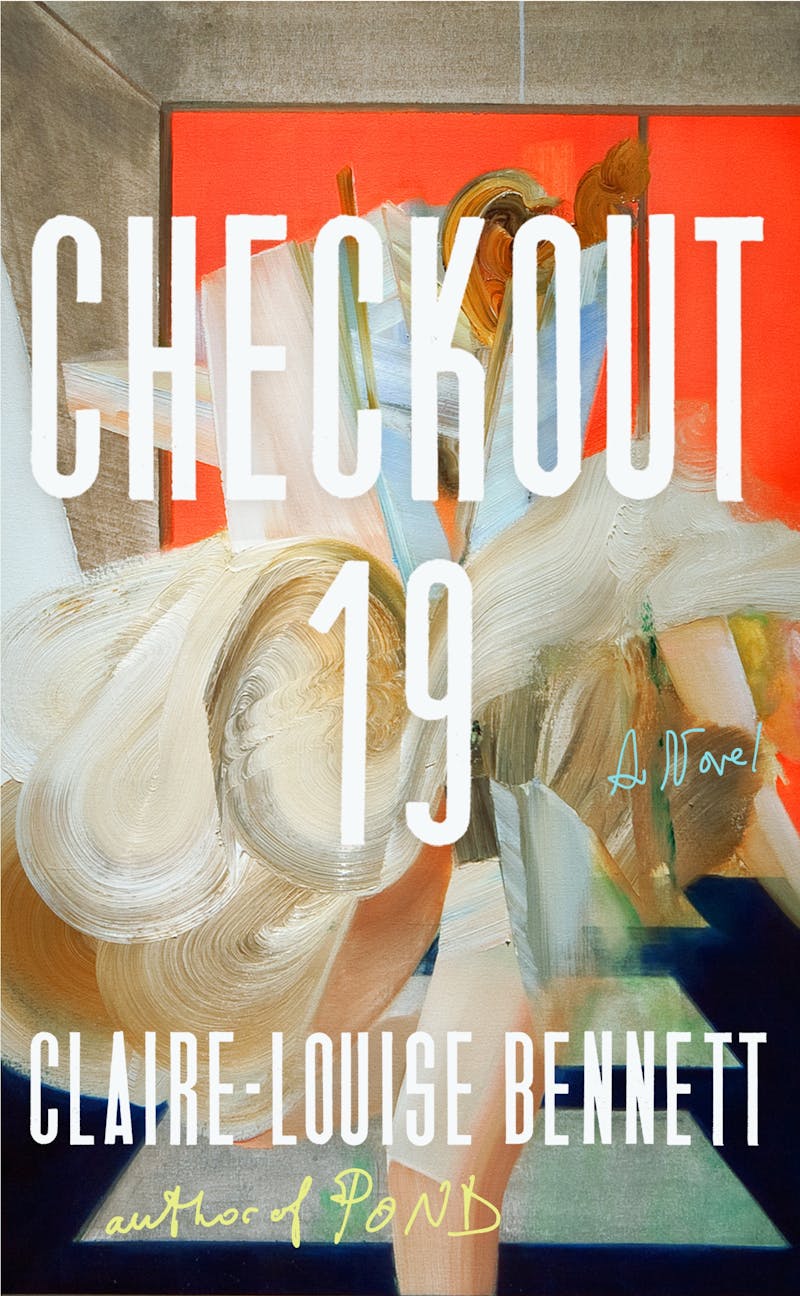

Claire-Louise Bennett’s novel Checkout 19

is both familiar and not. She’s precocious, grew up working class in southwest

England, and feels much like the woman we met in Bennett’s first book, Pond. We follow her from late childhood.

But the coming of age is not the one we might expect: Bennett reveals almost

none of her family life, briefly mentioning a brother near the end and making a couple of vague gestures

to parents. Instead, she tracks the narrator’s life almost solely through her

relationship to books: what she reads and writes and is told to read; what she

hasn’t read yet. For a while she only reads books about men. And then, for a

long time, she finds herself only reading books by women. Men try to tell her

what to read; sometimes she listens. She works briefly at a grocery store where

a Russian man who always finds his way to her checkout lane—19—gives her a copy

of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil.

She puts the book on a shelf next to her register.

The narrator writes her first story secretly, in the back of an exercise book at school in her favorite teacher, Mr. Burton’s, class. “It remained there on the page and the wound up fist sent the nib across the paper in a wavy line that flew up into exuberant loops,” she recounts, with an unusual focus on the physicality of the act and the appearance of her handwriting:

throwing off the tightness of the tight spirals that were a kind of steel wool obliterating the face that was so disgracefully wrong beneath, and then the loops sank down, calmer now, yes, calm now it seemed, a line again, a smooth line relaxing across the page and the line broke off into words, just a few words, then a few words more, and the words set out a story, as if it had been there all along. Within a matter of moments, there it was, a story—small and complete and indestructible.

When Mr. Burton finds the story, it is a shock at first: Her work is “something secret, something small that nonetheless disclosed the entranceway to an alluring and unmapped realm.” But then he asks her to share more with him. “I don’t know exactly how he put it. It was a very beautiful moment. It was beautiful at the time and now looking back it is perhaps even more so. It is precious. A precious moment.”

The language seems designed to unspool all the various layers of this moment. It’s too ornate to be consciousness; it feels instead like she’s holding the memory out in front of herself, trying to pick at all the various sensations it might hold: “He’d been somewhere he ought not to have been,” she reflects, as if talking about sex, a transgression, “and he wanted to go there again—that’s how it seemed to me.” He might want to transgress again, more risk and threat, but then she undercuts herself, puts the onus of this idea on herself. “OK, I said, I’ll bring some in for you to look at, and that’s what I did. I wrote stories and brought them in for him, every Friday.” Now the act of writing becomes something that she only does again because of him.

And so begins a journey, not just for the narrator of becoming a writer but also of the narrator grappling with the ways these moments have shifted and changed in her mind since. “I experience, every few years, an urge to recall this moment and the events that preceded it. Not only to recall it, but to write it down again. Again.” Nearly every pivotal moment that the book recounts is delivered this way: There is the thing itself depicted—often filled up with digressions—and then there is an often longer engagement with the way the thing itself now lives in the narrator’s body and her brain, how it has shifted and been altered over time and through the stories that she and others tell.

In many ways, much of this feels well worn in contemporary fiction: an unnamed narrator, hewing to the basic outline of the writer’s own life, focused on consciousness and not much plot. But if Rachel Cusk, as well as Jenny Offill, Kate Zambreno, Miranda Popkey, and Sarah Manguso all write sentences defined by a crisp cleanliness, Bennett’s sentences often feel like flights of fancy: They circle back on themselves, linger in uncertainties and contradictions—they feel like mismatched socks, a layered skirt, an oversize and multicolored cardigan thrown over an ornate silk button-up as opposed to Cusk’s unadorned simplicity. The excitement around Bennett’s books is connected in part to a sense of possibility: If a writer like Cusk confronts the reader with the power of a taut, single consciousness, Bennett is stretching the forms that consciousness can take to include effusion and hesitation, self-indulgence and equivocation. It’s just as brilliant, just as well read, but more willing to grasp for and circle sensations and ideas that don’t ever quite cohere.

At the outset, the unnamed narrator’s intellectual life is propelled almost solely by the writing and recommendations of men. There is Mr. Burton, for whom she started writing stories, but there is also the boyfriend who hates every book she recommends to him. There is Dale, the other boyfriend, whose “sense of narrative had always been much stronger than mine,” who tells her not to read Sylvia Plath or Anne Sexton. There are all the male writers that she reads.

I wanted to know about men, about the world they lived in and the kinds of things they got up to in that world.… I wanted to know the things they felt sad about, regretted, felt enlivened by, drawn towards, were obsessed with. I didn’t want to read about women. Women were sort of ghostly and they put me on edge.

It’s this very ghostliness that seems to propel much of this book: how to make sense of and acknowledge its amorphousness and also give it shape; the tenuous line between acting and being acted upon when you are trying to assert agency within systems built to constrain you.

Early in the book her grandmother talks of how, especially with women, “there is always more to this or that than meets the eye.” Bennett says later of this grandmother:

She didn’t talk about men much. I got the impression she was of the opinion that, as far as men were concerned, you could tell exactly what they got up to just by looking at them. And of course you could tell what they got up to just by looking at them since they went around getting up to whatever they pleased with no compunction whatsoever—women, on the other hand, were secretive and hid things and though it may have looked like they were doing one thing they were in fact quite often doing something else entirely.

Her grandmother sounds as if she is echoing a sentiment John Berger has expressed in Ways of Seeing: that men act and are; women are always appearing and also always cognizant of that appearing first.

A part of our narrator’s coming of age is her grappling with her body—how it holds both the brain that reads those books, that later writes them, and all its other messier, equally complicated parts. Threaded through the narrative of that story in the back of the narrator’s workbook—a secret then discovered to be a power—is the story of the narrator’s relationship to her menstrual blood: a pooling of it on the classroom floor, borrowed underwear, the washing of her skirt in the school bathroom, the switch from tampons to pads. The book does not equate the writing and the blood explicitly but is unrelenting in its willingness to linger in this space, to consider and then reconsider the different colors that the blood takes, interrupting the story of her writing; the power, fear, the thrill and violence of both of these experiences become inextricably entwined.

The middle of the book recalls the narrator’s years writing a story about a man named Tarquin Superbus. Bennett doesn’t tell the story itself but evokes the memory of the story, interspersed with the memory of its writing, interspersed with thoughts the narrator has had since. Tarquin Superbus is a wealthy man from “long ago” from either Venice or Vienna. The whole thing is absurdly fanciful, a lark—that name! One feels less enmeshed in Tarquin’s story for its own sake and more as if we’re being given a tour—as if it were an artifact or European castle—of what the story was or might have been.

Tarquin has a library filled with expensive books, but all the pages are blank. There is a single constantly disappearing (but magic and extraordinary) sentence that roams through them. The story cannot be offered to us in full, though, because the manuscript was destroyed by the narrator’s former lover, another man: “My boyfriend liked me being a writer, but didn’t very much like me to write. Writing took me away from him, to a place he didn’t understand and couldn’t get to, plus he was convinced I was writing about men all the time, and perhaps I was, some of the time.” And so we only get the memory of this story, its remnant, instead. “Yet I couldn’t quite discard the idea that in it somewhere there might have been a sentence, of such transcendent brilliance it could have blown the world away. And that idea burned in me on and on,” Bennett writes. And here’s the ghost again: She no longer has this story that she wrote because a man destroyed it; she still has the memory of it, but she also has the lingering ache of what the story might have been.

There was a point, rereading Bennett’s earlier book Pond, when I was grateful to remember it was a collection of stories, that the conceit of the form was one that I might dip into and out of, that I did not need to expect consistent forward momentum as I read. Because of Bennett’s ornamented, recursive style, there was a moment about three-quarters of the way through Checkout 19 when I got worried. OK, I thought. I get it, but where will this go? It began to feel like provocation: The affect never lets up—was it the book’s fault or mine that I felt the need sometimes to ask it to settle down?

Language and narrative are imperfect constructions, the standards of which were for a long time mostly policed by men. Checkout 19 follows the love of language and of books—the thrill of that love—with the realization that it’s all been built for someone else. For Bennett this is as much about the body that she lives in as the place and class she came from: “Imagine someone day in day out making you feel ashamed of the sound of your own voice.… We suspected that back then didn’t we … we were already angry. We were.” The fury and the devastation, the sense of loss and the uncertainty that comes afterward.

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche tracks two types of youth: a youth of saying yes to everything around you, of obeisance and placation, and a youth of saying no to everything, of refusal and rebellion. Until, he says, you realize that “no” was also youth, until you find a way to move forward without either self-abnegation or whole-scale rejection, you have not yet learned to live. Checkout 19 so thoroughly dispenses with so many of our linguistic assumptions and constrictions that it ends with an internal conflagration. It’s a story of compulsive intellectual consumption, followed by anger and rejection, concrete violence, but then for all the ways the end seems to be about burning and destruction, it’s also about what comes after that. Throughout Checkout 19 stories function as a catalyst not just for thinking but for acting, choices, lived experiences; it feels thrilling to imagine all the books and stories, the reconsidered ways of being, that might come after this.