Of course, January 6 was only the beginning. Republicans have turned against democracy, and peddlers of the Big Lie are laying the groundwork for the next coup. Experts tell us that a civil war might be around the corner, or that one is already here. After losing the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections, the GOP is using every tool at its disposal to impose minority rule: gerrymandering, voter suppression, a hammerlock on the judiciary, a Senate tilted toward small states, and an Electoral College biased in favor of rural America. If Democrats somehow manage to eke out a victory at the polls, state boards of elections honeycombed with Trumpists will simply throw out the votes. A second Jim Crow will arrive in full force, strangling the country’s dawning multiracial majority. It will be a tragic end for American democracy, but a fitting conclusion for a conservative movement born out of racist backlash and overseen by a reactionary elite that never reconciled itself to popular self-government in the first place.

At least, that’s the nightmare scenario keeping Democrats doom-scrolling late into the night and pushing liberal donors to open their wallets. But conservatives have their own story to tell. Yes, Republicans have struggled to win votes for the presidency, but the party has consistently pieced together national majorities in House elections, and it appears likely to do so again in the midterms this year. With centrist pundits fretting over the ascent of right-wing populism, a growing number of conservatives have cast themselves as tribunes of the people taking on the real ruling class—a Blue oligarchy wielding financial and cultural capital to stamp out the last flickers of resistance to its unholy union of woke capital, the deep state, and the mainstream media. If Republicans win a free and fair election, then liberals will write it off as proof that the voters just don’t understand democracy—and as another victory for the ghosts of Jefferson Davis and George Wallace in the battle for the soul of America.

It’s a game of “Choose Your Own Adventure,” except there are only two options, and they both end with democracy in ruins. Each vision of the future is shaped by a story about the past. Liberal dread of a gathering authoritarian revolt is the logical extension of a vision of American politics that centers on a clash between white supremacy and multiracial democracy reaching back centuries. Conservatives, meanwhile, depict today’s Blue oligarchy as the latest chapter in a history filled with liberals using lofty rhetoric—social justice, technocratic efficiency, “the science”—to slash American freedoms.

There is, however, one place where the stories converge. Left and Right both agree that what comes next depends on decisions made by the Republican Party—which is to say, by the conservative movement. Democrats warn that American democracy cannot survive another GOP victory. Conservatives, sensing Democratic weakness, are starting to catch glimpses of a reemerging Republican majority. Each has designed a strategy based on its story of how we got here. Which means that the future of American democracy could turn on which side better understands the history of the Right.

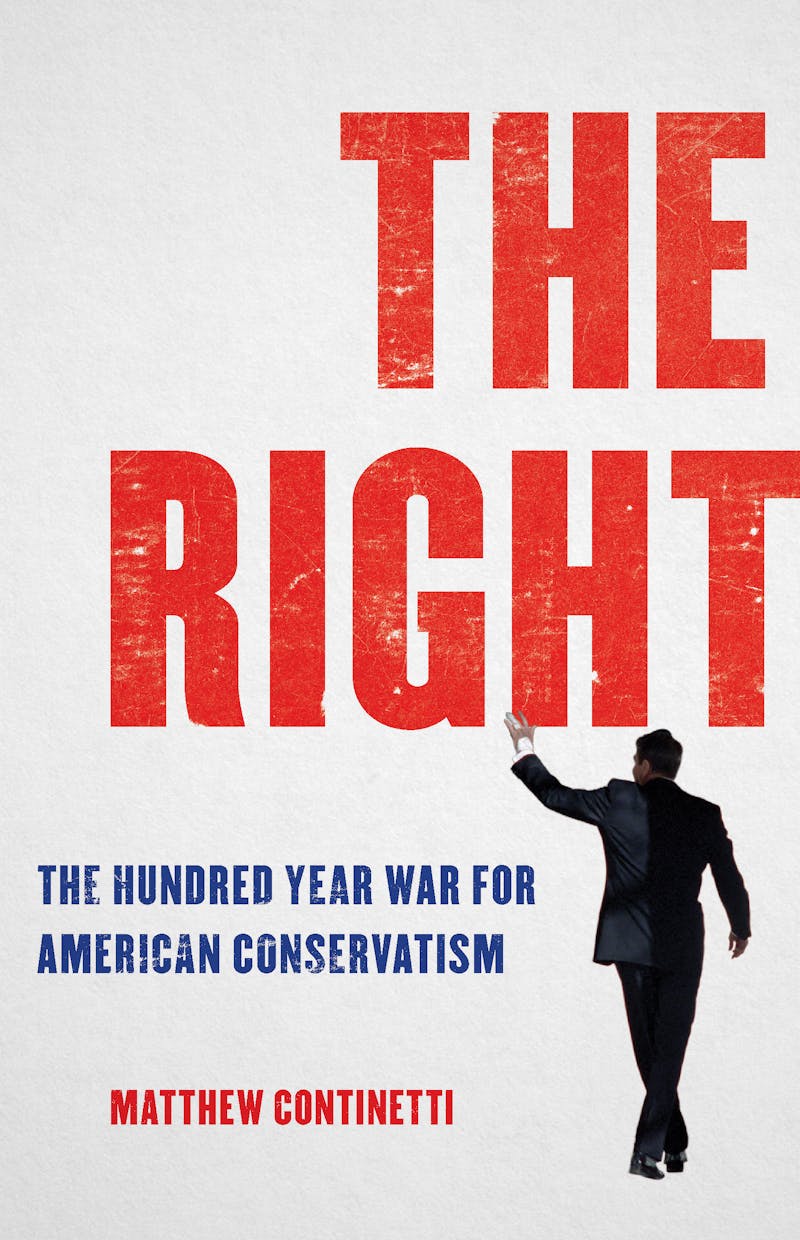

Matthew Continetti’s 500-page chronicle, The Right, arrives at a tricky moment for historians of conservatism. After languishing in historiographical backwaters for most of the last century, studies of the Right became fashionable during the George W. Bush years, when the conservative movement’s success forced an intellectual reckoning. Instead of tacitly assuming the inevitability of progress—with “progress” defined as secular, cosmopolitan, and liberal—historians looked to thinkers and activists they had previously relegated to the lunatic fringe. Typically, these accounts traced a journey from the margins to the center, following a road that led from the making of a self-consciously conservative movement around William F. Buckley Jr.’s National Review in the Eisenhower years to Barry Goldwater’s presidential run in 1964 and then to Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, closing with the Right’s permanent takeover of the Republican Party.

Then came Donald Trump. His victory in the 2016 GOP primary called into question the importance of the conservative elite that historians had just spent the better part of two decades legitimizing. And the short road from birtherism to the White House suggested that, by trying to take the Right seriously, earlier research had downplayed the conservative movement’s radicalism: too much Chamber of Commerce and National Review, not enough Ku Klux Klan and John Birch Society. For academics, the problem was as much a question of ethics as of scholarship. If Trumpism was the Right’s end point, then wasn’t it an act of naïvety—maybe even complicity—to pretend there was more to the story than crude bigotry?

Continetti has a different perspective. A senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, he is a creature of the conservative establishment. The Right begins in the summer of 2003, with his first day on the job at The Weekly Standard, where he had been hired fresh out of college. He promises an “insider’s perspective” on a history normally told at a double remove—by liberals rather than conservatives, and by academics rather than activists. “The conservative movement has been for me more than an abstraction,” he writes. “It has been my life.”

If anything, Continetti undersells his case. He entered the pipeline for young conservative talent while he was still in college, when he interned at National Review. And he eventually married the daughter of Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol, son of neoconservative intellectuals Irving Kristol and Gertrude Himmelfarb, making Continetti the Tom Wambsgans of the conservative establishment’s first family.

By his wedding day, Continetti had established himself as one of the Right’s rising stars. He had published two books and had just launched a new outlet, The Washington Free Beacon, backed by hedge-fund billionaire Paul Singer, and designed to serve as a conservative rejoinder to left-leaning websites like ThinkProgress. A presentable white guy with glasses and a full head of hair—imagine if Chris Hayes had a Republican cousin—Continetti was an ideal face for the respectable Right in the Obama era, a polite young man who happened to believe that fiscal responsibility entailed taking a meat cleaver to the welfare state. While Breitbart News was running a vertical on “black crime,” The Washington Free Beacon was earning praise from liberals for its commitment to breaking news. Continetti poked the establishment to get its attention, not to draw blood. “I don’t listen to talk radio,” he told an interviewer. “I listen to NPR.” To liberals, the signals were clear. He was on the Right, sure, but he wasn’t one of them.

And yet he could always be trusted to advance the conservative line with absolute sincerity. His second book, The Persecution of Sarah Palin, offered a prickly defense of “an unpredictable and courageous politician” in the grand American populist tradition. After the Tea Party made its debut, he celebrated the emergence of a grassroots movement devoted to “self-reliance, fidelity, piety, industry, and responsibility.” Continetti’s dreams of a populism fueled by entitlement reform had zero space for Occupy Wall Street. “Inequalities of condition are a fact of life,” he lectured as protesters were streaming to Zuccotti Park in 2011. “Some people will always be poorer than others.”

If one figure stood for Continetti’s ideal politician, it was Paul Ryan. A decade older than Continetti, Ryan was another clean-cut veteran of the conservative establishment. Continetti described him as the brains behind the Tea Party and called Ryan’s budget program—including major reductions in government spending, tax cuts tilted toward the wealthy, and privatization of Medicare—the GOP’s only “ambitious and intellectually coherent policy response” to a looming fiscal crisis. (Steve Bannon, who had a very different view of what fueled the Tea Party, called Ryan a “limp-dick motherfucker who was born in a petri dish at the Heritage Foundation.”) The details of Ryanism were politically toxic, but Continetti didn’t worry about the polls. “Ideas, even controversial ones, are not hindrances in politics but boosters,” he wrote. “They propel you to the top.” When Ryan looked set to take over as speaker of the House in October 2015, Continetti saw it as a coming-of-age moment for the Right’s next generation. “Liberals are terrified of what these young conservatives might accomplish,” he wrote. “Liberals should be.”

On the day Continetti proclaimed the onset of the Ryan Revolution, Donald Trump was the clear leader in Republican primary polls, pulling in a higher total than Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, and Jeb Bush combined. Continetti greeted Trump’s candidacy with equanimity at first. Of course, a reality TV star with a penchant for ludicrous conspiracy theorizing and crude racial demagoguery could never win. But a leader from the statesman’s wing of the GOP (maybe even—swoon—Paul Ryan) could translate Trumpian grievance mongering into a populist platform that would clobber Hillary Clinton in the fall. This was a common view in the establishment Right, one Continetti shared with his old boss at The Weekly Standard. “I’m once again drifting into the anti-anti-Trump camp,” Bill Kristol said at the time, describing Trump as a welcome challenge to “the cocktail partiers at Davos.”

Like his father-in-law, Continetti lost his composure when the bubble failed to burst. “The spectacle made me ill,” he wrote after watching Trump dominate a debate midway through primary season. “On screen I watched decades of work by conservative institutions, activists, and elected officials being lit aflame.” As Continetti fumed, the Free Beacon was paying the private research firm Fusion GPS to dig around in Trump’s background, not knowing that Democrats were also on the case.

Anger gave way to black-pilled acceptance for Continetti by the summer. “It’s a joke. All of it,” he wrote shortly after Trump clinched the nomination. “What disturbs me most is the prospect that Donald Trump is what a very large number of Republican voters want.” But he took comfort in the impending GOP debacle. “This is self-immolation on an epic scale,” he announced.

When it turned out that history had other plans, Continetti’s allies on the Right dwindled away. Some discovered a newfound appreciation for Trumpism. Others migrated to the left, or withdrew from politics. Over six months in 2018, anti-Trump conservatives lost one of their favorite pundits (Charles Krauthammer, to intestinal cancer), one of their favorite politicians (John McCain, to brain cancer), and one of their favorite periodicals (The Weekly Standard, to the whims of a billionaire owner who could see where the GOP was heading). Paul Ryan left Congress shortly afterward, ending the Age of Ryan before it started.

To be part of the mainstream Right now meant rejecting key tenets of the movement that Continetti had built his life around. He stepped down from editing the Free Beacon and took his post at AEI, a mainstay of the conservative establishment that has provided safe harbor for critics of Trump. The move freed up time for him to investigate where the Right had gone wrong, a problem that began gnawing at him even before Trump’s election. “The triumph of populism has left conservatism marooned, confused, uncertain, depressed, anxious,” he wrote in an agonized essay published in October 2016. “We might have to return to the beginning to understand where we have ended up.”

Continetti has returned from his voyage into the past with a history that portrays Trumpism as an understandable but not inevitable destination for the Right. It is, for reasons that we’ll come to shortly, far from a perfect book. But Continetti’s experiences have given him a valuable perspective on his subject. And in the education of Matthew Continetti—his time as a boy wonder for the conservative establishment, the shock of 2016, and his years of semi-exile—there are important lessons for the rest of us.

The driving force of Continetti’s narrative is a war lasting the better part of a century between what he calls “conservatives” and “the Right.” Conservatives are the Continettis of yesteryear, institutionalists quoting Edmund Burke to explain why staying credible with the mainstream is essential to moving the cause forward. The Right stands in for activists at the grassroots, latter-day Jacksonians willing to burn the whole system to the ground. Picture George Will on one side, Steve Bannon on the other. Continetti’s attention is most drawn to figures who tried to act as peacemakers in the battle between elites and populists—members of a conservative establishment speaking in the name of a right-wing base they didn’t entirely respect or understand, public intellectuals who wanted academic credibility without ivory tower isolation, activists taking donor cash while trying to maintain their independence.

Continetti’s story begins with a rosy account of life before the New Deal, in his telling a time when both the American public and its governing elite possessed an innate conservatism. The federal budget was just 3 percent of GDP, and rapid economic growth eased tensions between capital and labor. Republicans were the party of the mainstream, and they reaped the electoral rewards, winning three presidential elections in a row by landslide margins and controlling the House and Senate for the entire decade. Continetti acknowledges that this conservative Eden had its share of snakes—a resurgent Ku Klux Klan, the Tulsa Massacre—but the abiding impression is of a lost golden age whose faults could have been corrected through incremental reform.

The Great Depression shattered this world, and gave New Dealers the opportunity to make a different one. By the time Harry Truman left the White House in 1953, Democrats had transformed the country, including the elite, which now had a decidedly liberal (though far from radical) orientation. But after decades of political dominance, FDR’s majority was coming apart. McCarthyism had given conservatives a populist makeover by linking anti-communism to the campaign against big government. Civil rights activists were pushing debates over racial justice to the foreground, providing Republicans with an opportunity to break open the solidly Democratic South that had been the base of Roosevelt’s coalition. The establishment was becoming more liberal, discontent with the status quo was bubbling, and the GOP was poised to attack a New Deal order that was already cracking under the weight of its contradictions.

Here is where the dynamic that powers Continetti’s history—the tension between “conservatives” and “the Right”—locks into place. In the 1920s, he notes, conservative thinkers typically looked at democracy with contempt, while grassroots activists took second place to Republican bosses with a firm grip on the party machine. Jump forward to the 1950s, and the revolt against the liberal establishment had drawn the intellectuals into politics while strengthening populists in their battle against the GOP’s old guard. These two unlikely allies were joined together by their commitment to overthrowing the New Deal, forging a marriage of convenience that gave rise to the modern conservative movement.

It was never going to be a blissful union. “To live,” Whittaker Chambers told a young William F. Buckley Jr., “is to maneuver.” Buckley referred to the line often, and it’s easy to see why. While he was trying to bestow intellectual legitimacy to the conservative movement through the urbane journal he founded, National Review, the head of the John Birch Society was telling his followers that Dwight Eisenhower was in all likelihood a Soviet agent. Conservative elites were forced into the role of gatekeepers, trying to harness popular discontent without handing control of their movement to lunatics muttering about fluoride. In Buckley’s case, this meant taking to the pages of National Review to warn Birchers that they could not succeed if they listened to “a man whose views on current affairs are ... so far removed from common sense.”

Buckley’s move went down in conservative lore as the purging of the Birchers, after which Republicans settled into an informal arrangement whereby populists supplied the votes and elites dictated policy. In the 1970s, grassroots activists calling themselves “the New Right”—ERA-slayer Phyllis Schlafly, Moral Majority founder Jerry Falwell, direct-mail guru Richard Viguerie—brought activists to the polls. But it was neoconservative intellectuals who shaped the conversation in the Capitol and scored the sweetest think tank sinecures. Under Reagan, the conservative movement grew into a proper conservative establishment located in Washington and dominated by Ivy Leaguers speaking on behalf of the heartland. A dissident intellectual wing of paleoconservatives bemoaning the rise of “Conservatism Inc.” later rallied behind Pat Buchanan. By the time George W. Bush was sworn into the presidency, however, Buchanan had been driven out of the Republican Party, and Buckley’s heirs had matured into what Continetti describes as a “self-confident conservative ruling class.”

Although Continetti steers clear of insider gossip, his description of life in the conservative machine has the feel of an eyewitness account. “Young conservatives,” he writes,

started off as reporters or production assistants at a newspaper, magazine, radio show, or television network. Then they moved to the Hill as speechwriters or legislative assistants. Then they took a turn at a consulting shop or as corporate speechwriters. Then perhaps they advised a donor, or managed a campaign, or someday ran for office themselves. At any point in this journey, their connections, ingenuity, and good luck might make them fantastically rich. Then they would pour their resources back into conservative foundations, networks, and institutions.

This was the conservative establishment that Continetti joined when he moved to Washington. And it’s the system that Trump drove a bright-red truck through.

Continetti has a more favorable opinion these days of the man he once called “a misogynist and bigot, an ignoramus and doofus.” With Trump’s presidency safely in the rearview mirror, for now, Continetti describes the doofus of 2016 as “a disruptive but consequential populist leader,” who was only forced into “the ranks of American villains” by his crusade to overturn the 2020 election. (He notes, too, that most of Trump’s signature achievements could have been the handiwork of a President Rubio: tax cuts, deregulation, and a litany of judges stamped with the Federalist Society’s seal of approval.) But he cannot resist casting a mournful look at the institution that Trump did the most to disrupt. Even if the White House borrowed much of its agenda from GOP orthodoxy, Trump’s rise “disestablished the postwar conservatism of Buckley and Goldwater, of Irving Kristol and Ronald Reagan, of William Kristol and George W. Bush”—and, he could have added, of Matthew Continetti and Paul Ryan.

Except the story of the American Right isn’t so simple. Because, as Continetti’s own research shows, even when gatekeepers tried to draw a bright line between a respectable establishment and unhinged populists, time and again the divide broke down in practice. Historians will already be familiar with most of Continetti’s examples of collaboration between elite conservatives and the grassroots Right, but seeing them parade one after another through the decades makes its own kind of argument. Conservatives and the Right weren’t fighting a war. They were partners in a joint venture kept alive by strategic silences, willful blindness, and mutual self-interest. Together, they cleared a path that led directly to Donald Trump. And Continetti is a good enough historian to mark the key points in this itinerary, even if he isn’t willing to reckon with the implications of his own findings.

Consider, for instance, the purging of the Birchers. Continetti is clearly on Buckley’s side, but even his sympathetic account leaves the mythology in tatters. Buckley’s turn against JBS founder Robert Welch came after years of dancing around the issue. When he was finally dragged into the fight, Buckley took pains to exclude Welch’s followers from his critique. This was less of a purge than an attempt to maintain plausible deniability. As Continetti explains, Buckley was responding to the logic of his situation. “Conservatism could attain neither elite validation nor nationwide success if it was associated with Birchism,” he writes. “But it also could not sustain itself if Birchism was excised—it would have no constituency.”

Buckley was used to dealing with this kind of problem. Birchers were following a template set by Joe McCarthy, and in the months before National Review was founded, Buckley took time out of a busy schedule to speak at a dinner in honor of McCarthy’s chief legal counsel, Roy Cohn—not a surprise, given that he had published a book-length defense of McCarthy earlier in the same year. National Review’s first contributors included an antisemite who endorsed the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (the palindromically named Revilo Oliver). Its chief political correspondent, James J. Kilpatrick, was a proponent of “massive resistance” to school integration who in 1964 wrote, “the Negro race, as a race, is in fact an inferior race.” Buckley himself drafted the magazine’s 1957 vindication of white supremacy below the Mason-Dixon line, “WHY THE SOUTH MUST PREVAIL.”

Although Buckley later recanted his views on segregation, influential figures at National Review took the lead in arguing that Republicans should build a new majority by weaving together supporters of Ronald Reagan and George Wallace. “The only practical solution,” the magazine’s longtime publisher William Rusher wrote in a 1975 New York Times editorial, “is for conservative Republicans (broadly represented by Reagan) and conservative Democrats (most of whom have in the past supported Wallace) to join forces.”

Reagan, National Review’s most famous subscriber, took Rusher’s advice to heart. The young man who came of age idolizing FDR grew into the politician who rode the support of New Right favorite Jesse Helms to victory in the North Carolina primary in 1976. The New Right brought Reagan votes and gave him a strategy for building, as he put it, a “New Republican Party” with “room for the man and woman in the factories, for the farmer, for the cop on the beat,” united “against the tyranny of powerful academics, fashionable left-wing revolutionaries, some economic illiterates who happen to hold elective office, and the social engineers who dominate the dialogue and set the format in political and social affairs.” Without this mix of New Deal style and New Right substance—the happy culture warrior—Reagan would have run into the same electoral dead end that Barry Goldwater did.

For more evidence of the messy overlap between populists and the establishment, Continetti could have looked to The Weekly Standard. He notes that David Brooks was once a senior editor at the magazine but doesn’t say that Tucker Carlson—now far and away the most influential right-wing pundit not named Trump—was one of its first writers. “Kristol was always encouraging me to write hit pieces on Pat Buchanan,” Carlson has said. “He saw himself as the ideological gatekeeper of the Republican Party.” The problem was that, aside from foreign policy, Kristol and Buchanan didn’t disagree on much, including social issues. “In private,” Carlson says, “Kristol was as witheringly antigay as Buchanan was in public.” (It must have been awkward, too, that Buchanan’s sister Kathleen was Kristol’s assistant.)

Continetti doesn’t comment on his father-in-law’s language behind closed doors, which is understandable. But he also doesn’t mention that Kristol spearheaded the campaign to choose Sarah Palin as John McCain’s running mate in 2008. Although Kristol and Brooks have moved toward the center-left, many of the leading thinkers on the Trumpishly inclined Right—including Sohrab Ahmari, Michael Anton, and Christopher Caldwell—were published in the Standard. “We’d like to dislike Bill Kristol,” one of the young attendees at the National Conservatism Conference told Brooks. “But he got us all jobs.”

Meaningful silences with respect to his old employer aren’t the only times when Continetti shades the narrative to place his subject in a softer light. He acknowledges that conservatives have appealed to prejudice, but for the most part he spares readers details of the paranoid theorizing and violent extremism that have always been part of the movement, and that loom so large today—leading, for instance, to a discussion of the Trump era that leaves out QAnon, the Proud Boys, and the Oath Keepers. While he’s too gentle with the Right, he’s often just clumsy with the Left, from wrongly suggesting that New Dealer Adolf Berle was a communist fellow traveler to lumping poor George McGovern alongside the Weathermen and Black Panthers as examples of left-wing extremism.

This, in short, is a book that gets a lot of things wrong. But it gets one big and important thing right. By illustrating how much today’s right-wing populists owe to yesterday’s establishment conservatives—their successes, failures, and all the compromises made along the way—Continetti demonstrates that there are no sharp breaks in the history of the Right, only partial victories in a constant struggle. Trump’s election wasn’t divine retribution for conservatism’s original sins. It was just politics, the result of both long-term structural trends and choices shot through with contingency. Which means the fate of the Right is still up for grabs. And so is American democracy.

“When you study conservatism’s past,” Continetti writes, “you become convinced that it has a future.” Trump’s shadow hangs over that future today. It’s easy—very easy—to imagine Republicans succumbing to an electorally toxic embrace of Trump, then tipping the political system into chaos by refusing to concede defeat.

Continetti is pinning his hopes on a different outcome. Too young to retire, too sincere an ideologue to join the Resistance grift, he has traded his orthodox conservatism for a buttoned-up populism that steers a middle course between NeverTrumpism and full-bore MAGA conversion, heavy on a tempered version of the culture war but willing to ditch the authoritarianism: yes to campaigning against critical race theory, no to overturning elections. A movement of Glenn Youngkins and Ben Shapiros isn’t quite the cause that he signed up for back in college. But, with The Weekly Standard now a footnote in conservative history and Paul Ryan making the rounds on corporate boards, it’s a gamble that Continetti is willing to take—and it might pay off.

Trump’s autocratic instincts made it difficult to see that he pointed the way toward a plausible strategy for building a new Republican majority. By breaking zombie Reaganism’s grip on the party (at least rhetorically), he created space for a platform that ditched entitlement reform while ratcheting up the attacks on a clueless establishment—not a bad formula for winning at the polls, especially in the swing states that decide national elections. With voters on their side, it would be possible for Republicans to drop the direct assaults on democracy and go back to doing what, over the last half-century, the party has done best: convert cultural grievance into tax cuts for the rich. The United States would become a meaner, harsher, crueler place to live, all without a single militiaman having to storm the Capitol.

And it’s not clear how liberals would respond. However nightmarish the Trump years were for Democrats to live through, they were a heady time for activists on the left. Trump’s open race-baiting combined with his loss in the popular vote allowed liberals to assume they had a righteous majority on their side. Billions of dollars sluiced through a network of think tanks, activist groups, and foundations, creating a whole ecosystem filled with reformers who believed the country was waiting to be called to a higher purpose by leaders with a bold agenda for resolving a crisis of democracy. Now we just might find out whether the public agrees.