In

1955, C. Vann Woodward, the nation’s preeminent historian of the South,

published a brief history of Southern segregation that Martin Luther King Jr.

would call “the Bible of the civil rights movement.” The Strange Career of

Jim Crow, as the book

was titled, was intended to counter a common defense of segregation at the time—that

it had “always been that way.” By

showing that legal segregation emerged only in the 1890s, and only after

attempts at interracial democracy during Reconstruction were overthrown,

Woodward provided civil rights activists with a usable past: a short but

rigorous history that could serve the cause of desegregation.

Kris Manjapra’s brief and important new book, Black Ghost of Empire, fits squarely within the usable past genre. To make the case for reparations in its broadest sense—not just for monetary compensation but also for a genuine repair of the relationship between Black and white people—Manjapra examines not slavery itself but the inequalities that arose during emancipation. Manjapra, an accomplished historian of race and colonialism at Tufts University, argues that wherever one looks, the legal process of emancipation was more or less the same: Slaveholders, not slaves, were given monetary compensation when slaves were freed, and new forms of racial exploitation emerged that only “prolonged and extended the captivity and oppression of black people around the world.” By highlighting the long afterlife of slavery—and the many new forms of racial oppression that emerged in slavery’s wake—Manjapra takes direct aim at the idea that abolishing slavery was enough.

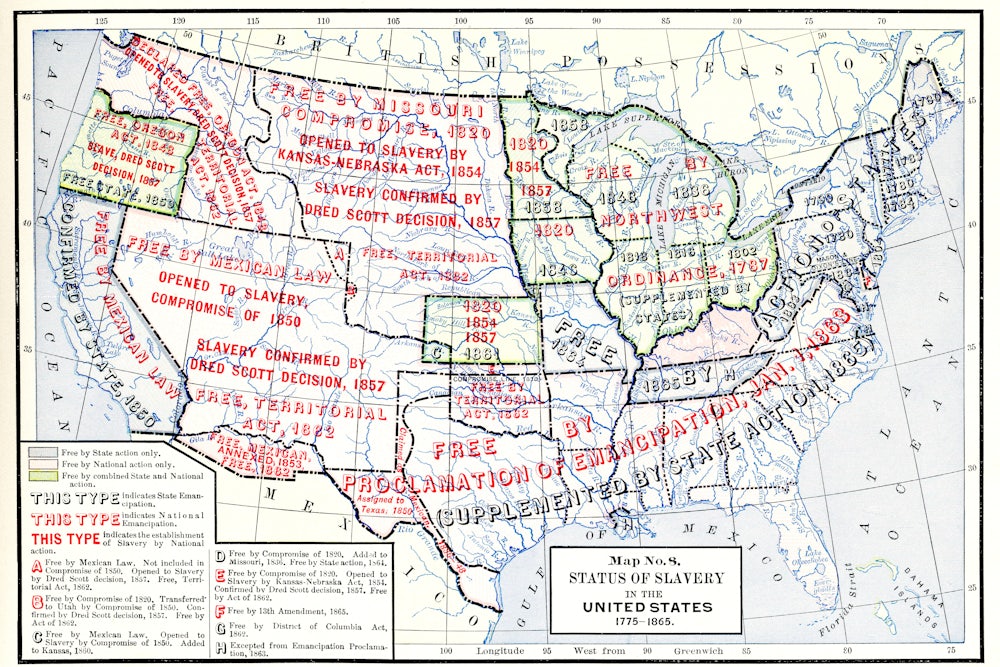

A great strength of this book is its sheer sweep. Manjapra details how emancipation unfolded not only in the Northern United States and then the entire nation but also in Latin America, Haiti, the British empire, and Africa. The gradual emancipation that began at the state level in the U.S. North, he argues, provided the template that other European colonies and states in the Americas would follow. In 1780, Pennsylvania enacted the nation’s first gradual emancipation law, in which slaveowners were compensated not with cash payouts but with the prolonged service of enslaved Black people. Only enslaved children born after the law went into effect were freed, and only after serving for 18 years.

In the subsequent two decades, all the other Northern states followed suit, enacting laws so lenient that slaveholders could, with minimal effort, recategorize enslaved people as “servants,” “indentures,” or “apprentices” and still remain within the letter of the law. In 1804, New Jersey became the last Northern state to enact a gradual emancipation law, but Manjapra shows that it was so meekly designed that by 1830, the state held two-thirds of the North’s enslaved population, and it did not fully abolish slavery until 1846—although, again, owners could keep their former slaves as “apprentices.” In truth, Manjapra writes, slavery did not completely end in the North until it ended in the South, with the Civil War.

Black Ghost of Empire gives very little space to Latin America, only to note that the emancipation laws of most Latin American republics explicitly followed the logic of the Northern U.S. The interests of slaveholders and the sanctity of private property, not the lives of Black people, were prioritized, usually in the form of “freedom of the womb” laws that gave children born to enslaved women freedom only after years of service.

Haitian emancipation is often seen as the one great counterexample to the gradual emancipations of this period. In Haiti, enslaved people staged their own war for freedom, winning not only complete, immediate, and uncompensated emancipation but also, by 1804, a free and independent Black republic. But that is not how Manjapra sees it. He focuses instead on what came after independence, noting that no Western country would give Haiti full recognition as a sovereign nation until it agreed to pay its exiled planter class and their descendants compensation. Only in 1825, after 20 years of isolation, did France begin the process of normalization by forcing Haiti to pay the equivalent of $37 billion in today’s dollars. Though later reduced to $22 billion, the payout at times consumed 80 percent of the Haitian government’s annual budget, prevented the nation from investing in its own schools, roads, and hospitals, and was not fully paid off until 1947. “To pay former French masters,” Manjapra writes, “Haiti would be forced to starve its children and deprive its communities for generations.”

British emancipation was strikingly similar. In 1834, Parliament enacted a gradual emancipation law in the British Caribbean with a transitional “apprenticeship” period. But in the face of enslaved resistance, Parliament emancipated all its 800,000 Caribbean slaves immediately in 1838, compensating slaveholders to the tune of $20 billion in today’s currency, which slaveholder families used to invest in American railroad companies and British imperial holdings in India, Egypt, and Australia. Meanwhile, after Brazil became the last nation in the Western hemisphere to abolish slavery in 1888, Britain and six other European empires turned their attention to Africa. Under the guise of liberal interventionism—in this instance, stamping out slavery—European powers colonized 90 percent of the African continent by 1900, technically ending slavery but in reality forcing Africans and imported Asian laborers to work the diamond mines and rubber plantations that continued to fuel European empires.

When Manjapra puts the Civil War’s emancipation in this context, he sees more similarities than differences. Though U.S. historians often characterize the postwar Reconstruction period from 1865 to 1877 as a brief if ultimately failed experiment in interracial democracy, Manjapra sees it as a process that simply “perpetuated the war on black people, rather than ending it.” Though Black Americans were granted freedom and full citizenship, and by 1870, Black men received the right to vote, emancipated Black Americans were denied the thing that the overwhelming majority of them demanded: free land, similar to the free land, or homesteads, granted to white Americans in the West during the Civil War. Instead, all they got, in Manjapra’s telling, was the government-run Freedmen’s Bureau, which under the guise of adjudicating fair labor contracts, forced Black people to sign oppressive contracts that kept them landless and dependent on their former masters long into the twentieth century. As the saying goes, the North may have won the war, but the South won the peace.

To its immense credit, Black Ghost of Empire shines a light on what popular understandings of emancipation often leave out: that emancipation both within and beyond the U.S. often sought to placate the economic interests of slaveholders, while denying Black people any sustained protection from their former owners or the economic means that might ensure genuine Black equality. To highlight this fact certainly adds weight to the moral necessity of reparations, but in its relentless focus on the real failures of emancipation, it privileges a deeply pessimistic interpretation of the past that may in fact undermine its cause.

Rather than understanding Black people as agents of their own emancipation, Manjapra presents them as victims of the political processes that set them free. While Manjapra provides ample space for Black resistance, so concerned is he with prosecuting emancipation laws and the white abolitionists who advocated for them, that he either ignores or downplays the ways enslaved and free Black communities created the political context that made these laws possible and the ways Black communities often endorsed these laws and used them to push their struggle forward. Take Northern gradual emancipation laws. Despite their many flaws, they resulted in the overwhelming majority of Black Northerners becoming free by 1830, and the free Black communities that these laws made possible became central agents in the ultimate extinction of slavery nationwide.

Free Black communities housed the tens of thousands of fugitive slaves who escaped from the South in the decades before the Civil War, and these fugitives helped catalyze Northern opinion against slavery, if not racism itself. Moreover, it was free Black communities’ articulation of a more radical, immediate, and uncompensated end to slavery that convinced many white abolitionists, mostly notably William Lloyd Garrison, to adopt a similarly uncompromising position on slavery. The views of radical abolitionists, Black and white, were undoubtedly a minority in the moderate white North. But they had an outsize role inflaming the sectional divide, and ultimately their vision of emancipation—immediate, uncompensated, and full Black citizenship—won out during Reconstruction. No one doubted that Reconstruction laws were imperfect—most obviously in their failure to give freed people land—or that Northern white support for Black freedom might be fickle. But rather than reject Reconstruction laws and government entities like the Freedman’s Bureau, they used them to protect their fragile freedoms and fight for the ones that remained to be realized.

Under the Freedmen Bureau’s aegis, hundreds of thousands of freed Black people received a formal education. And during the Reconstruction period, poor Southern whites and freed Blacks created the interracial political coalitions that created the South’s first public schools, hospitals, and poverty assistance programs. Even after the federal government ended its military occupation of the South in 1877, effectively ending Reconstruction, powerful, working-class interracial coalitions appeared. Between 1879 and 1883, in Virginia, the Readjuster Party, a coalition of freed Black people and small white farmers, won the governorship and a U.S. Senate seat, using their power to progressively tax the former planter class and redistribute that wealth to poor white and Black sharecroppers alike. To boot, one of its leaders was a former Confederate general. None of this would have been possible had Reconstruction not occurred and had not freed Black people been willing to work with white politicians of whom they had every reason to be skeptical.

In Manjapra’s telling, there is little room for these interracial, populist coalitions, ones that achieved tangible gains. Instead, he is more invested in recovering pan-Africanists of the past whom he believes light the way toward true historical redress. Yet here too Manjapra gives us only a selective reading of the past. Many of the nineteenth-century diasporic pan-Africanists he highlights, whether the free Black American sailor Paul Cuffe or Nora Antonia Gordon, a Spelman graduate and Christian missionary, held views of Africans that were not dissimilar to those of liberal white humanitarians. By bringing Christianity, commerce, and civilization to Africa, many of these early pan-Africanists believed, they would regenerate the African continent and improve the image of Africans abroad. Manjapra does not stop to ask what indigenous Africans, in all their diversity, might have thought of these curious African American missionaries, and how indigenous African visions of the future might have differed from those of the diaspora.

Manjapra is rightly focused on challenging a liberal triumphalist account of slavery’s demise. But in the process he obscures how specific political contexts shaped Black emancipations. In Black Ghost of Empire, one hears precious little about how the American, French, and Latin American revolutions—to say nothing of the Civil War—provided Black people with both the political language and material circumstances to fight for and win their own freedom. Manjapra seems worried that, in highlighting how, for instance, the revolutionary-era rhetoric—freedom and equality—contributed to early Black emancipations, we rob Black communities of their independent movements for freedom. But one need not downplay the reality that Black people had been fighting for their freedom from the very moment they were enslaved to recognize that they were equally attuned to the broader political context around them. Black communities achieved their greatest acts of self-liberation not by ignoring these political currents but by seizing them and shaping them to their own ends. Eliding this broader context not only misinforms readers about how Black people actually won their freedom, it oddly robs them of the very political sophistication Manjapra seems intent on restoring.

The deeply pessimistic view of emancipation Manjapra’s book embodies will undoubtedly appeal to certain readers. But whether it will ultimately help the cause of reparations—a moral and political necessity—remains to be seen. Perhaps the most useful histories that might serve the cause of reparations will not focus exclusively on how slavery ended but on the nearly four hundred years of slavery itself.