The summer of 1755 was a terrible time for George Washington. The 23-year-old Virginian slaveholder was serving as an aide to the British general of North America, Edward Braddock, in the Battle of the Monongahela. At the time, colonists like Washington still considered themselves proud subjects of the British Empire. But the routing that Washington was about to receive set in motion the steady unraveling of the imperial relationship.

French soldiers, along with their Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potowatomi allies, fended off Braddock and Washington’s assault near what is today Pittsburgh, killing a third of their 1,500 troops, along with Braddock himself. To many of the Indigenous nations involved in the battle, Washington was already a well-known figure. His family was one of seven wealthy Virginia developers that created the Ohio Company in 1748, which laid claim to millions of acres of Indigenous-inhabited land west of the Appalachian Mountains, including places like Pittsburgh. Iroquois nations even had an epithet for the Washington family: Connotacarious, meaning “devourer of villages,” a name Washington gleefully embraced.

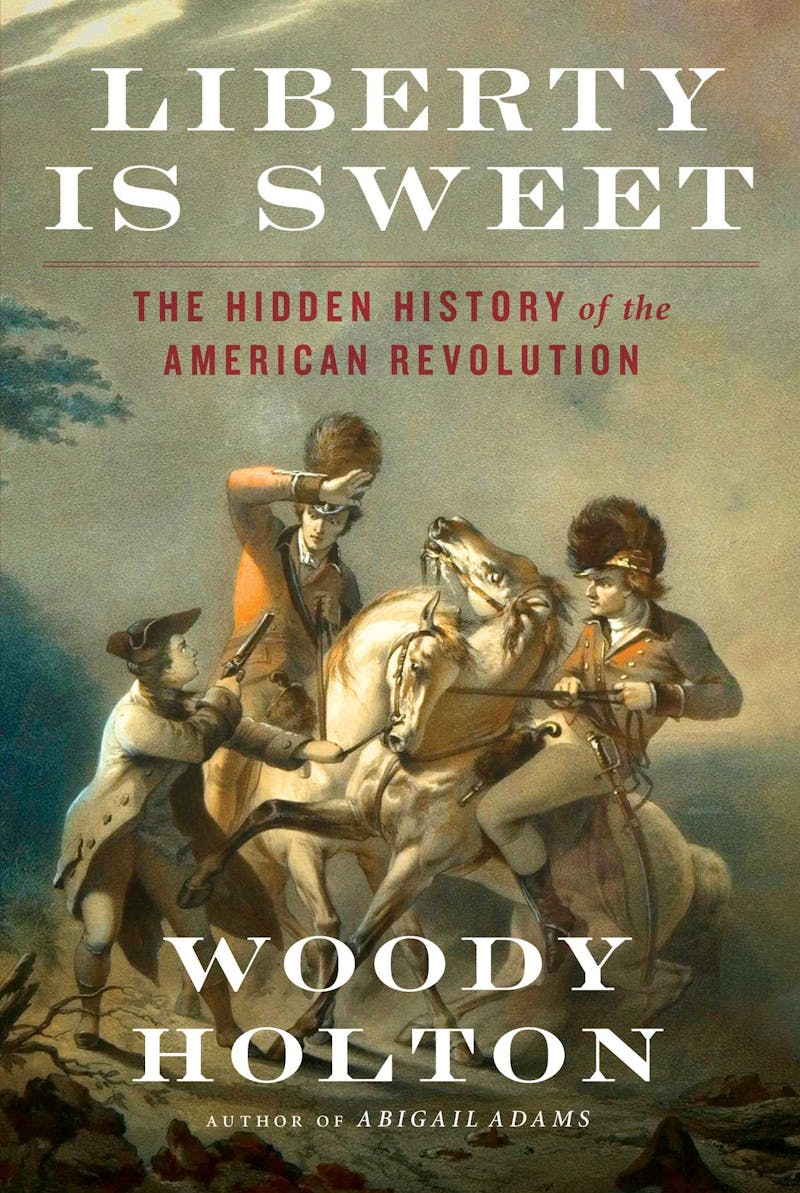

The Battle of Monongahela was the first major conflict in the French and Indian War of 1754 to 1763. But in his new history of the American Revolution, Liberty Is Sweet, Woody Holton sees it as the starting point for the War of Independence, which traditionally begins in 1775. In Holton’s account, the revolution had its roots, above all, in colonists’ desire for Indigenous land. By 1763, the British and their American colonists finally defeated the French and their Indigenous allies. But the British did not allow colonists to settle on the newly gained ground. They stationed 10,000 British soldiers in frontier garrisons, functioning as peacekeepers between Native Americans and backwoods settlers. To pay for those troops, Parliament issued the Stamp Act and the American Duties Act, the latter of which renewed taxes on New England’s chief import—slave-grown Caribbean sugar—and clamped down on its smuggling of cheaper French and Dutch slave-grown sugar. The final straw came between 1773 and 1774, with a series of onerous laws that Patriot leaders dubbed the Intolerable Acts: laws that forced colonists to house British soldiers, shut down New England town meetings, closed Boston’s ports, and not least, transferred prized western land in the Ohio River Valley to the new British colony in Quebec.

A great strength of Liberty Is Sweet is that it refuses to paint either the colonists or the British Empire as simple villains or victims. Indeed, Holton believes that too many popular histories of the revolution have become a “revolt against complexity.” The British, he tells us, may have acted reasonably by raising taxes on the 13 colonies, but they were also in league with Caribbean slaveholders. Rural colonial farmers, meanwhile, were justified in opposing imperial policies, which were, after all, meant to bail out slaveholders and bankers. Yet just when we think we have found Holton’s heroes, we are reminded that many of these same rural farmers are the ones who most desperately craved Indian land, as well as enslaved people to work it.

What is striking is that this complexity has been entirely missing in the recent public debates surrounding Holton’s book. In July, Holton published an op-ed in The Washington Post arguing that British officials’ offers of freedom for service to enslaved Black Americans pushed many white Patriots to declare independence. Immediately, critics from across the liberal-to-left spectrum pounced, seeing Holton’s op-ed, and the yet-to-be-published book it promoted, as reviving the argument made by The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which also highlighted slavery’s role in prompting the declaration. Socialists accused him of being a race-reductionist, seeing racism as the central explanation for all of American history. His liberal scholarly critics sympathized with his goal of highlighting racism’s role in America’s past but argued that he was grossly distorting the facts to do so. Holton has since doubled down, engaging in a recent, heated debate with Gordon Wood, another prominent scholar and fierce 1619 Project critic, who has long battled revolutionary histories written “from below.” But to see these debates, which center around slavery’s role in the American Revolution, as a reflection of the book’s main content is to miss the many causes and characters Liberty Is Sweet actually covers.

As Holton moves from the French and Indian War to the War of Independence, he spends much time on the battlefield. Though he has a gift for pacing and narrative detail, this section, by far the longest of the book, can begin to feel antiquated. But Holton is attuned to what is sometimes called the “new military history” and therefore offers intriguing details about how people and events off the battlefield—wars in India, slave revolts, women’s boycotts—as well as the resistance of poor white soldiers to duplicitous recruitment schemes, shaped the war’s outcome. Indeed, one of Holton’s aims is not simply to offer an “inclusive” history—one where ordinary people are just added to a familiar frame—but to show us how including a wider swath of society can help us rethink the picture itself.

Like many scholars, Holton underscores the critical role that slavery played in hastening Southerners’ support for the Patriot cause, even if slavery was not the only factor. Many Southern whites worried that the British would end the institution of slavery; as early as 1774, white Virginians reported a rumor of a planned slave revolt “when the English troops should arrive.” A year later, Lord Dunmore, the Virginia governor who stayed loyal to the British, offered freedom for service to any enslaved man belonging to a Patriot owner (but not a Loyalist). Dunmore’s proclamation sent shock waves throughout the South. “The Proclamation,” wrote one Virginian Patriot, “has had a most extensive good consequence.… [White] Men of all ranks resent the pointing a dagger to their Throats, thru the hands of their slaves.”

Four years later, as the war dragged on, the British General Henry Clinton expanded the proclamation, offering freedom to “every Negro”—man or woman, with or without military service—“who shall desert the Rebel Standard.” Indeed, it was Clinton’s proclamation, as much as Dunmore’s, that transformed the war. By the war’s end, at least 20,000 enslaved men and women, and perhaps many more, had escaped to British lines. The Continental Army, meanwhile, refused to offer a similar freedom-for-service decree, fearful that it would alienate Southerners (although desperate for troops, it eventually allowed at least 5,000 enslaved men to enlist). Meanwhile, Southern Patriot leaders became so starved for soldiers that they began to offer hundreds of acres of Indian land—as well as one slave—to any white man who would fight. In the South, then, it is entirely reasonable to argue, as Holton does, that many white Patriots fought to preserve slavery as much as they did to attain their own freedom.

But there is much more to Holton’s narrative than slavery. Ultimately, Holton contends, the Patriots won the war in large part because the British military was stretched thin, fighting not just within the 13 colonies but in other reaches of its global empire. Britain had taken over much of France’s Indian colonies in 1763, but Haidar Ali, the ruler of a town in southern India, continued fighting, mounting a series of devastating military blows against Britain’s East India Company, the private corporation that governed India for the British. Ali’s military campaign between 1767 and 1769 effectively bankrupted the company, pushing Parliament to bail it out, in part by forcing American colonists to purchase its tea. Then, in 1780, Ali orchestrated another devastating strike against the company’s headquarters, compelling Parliament to pull troops from the American theater and redeploy them in India. Though it’s largely forgotten today, Patriot elites celebrated Ali as a hero of their own revolution: “Heyder Ali is the standing toast of my table,” said Benjamin Rush, a Patriot leader, upon hearing of Ali’s victories.

This lesser-known story is a reminder that the War of Independence was not only fought between Loyalists and Patriots. It was a global war, in which the involvement of several other powers proved crucial to the Patriots’ success. When Patriot leaders finally got France and Spain to aid them, in 1778 and 1779 respectively, the British realized that their entire global empire, not just the 13 colonies, was at stake. With good reason, the British worried that both the Spanish and French might try to seize territories lost to Britain in the century’s previous wars. By 1780, the British removed a third of their troops from the 13 colonies, restationing many of them in the Caribbean in order to protect their most valuable colonial asset: their slave-based sugar colonies. Holton also reminds us that the final major battle at Yorktown, in 1781, was won largely by the French military, who outnumbered Patriot troops two to one. In many ways, Holton suggests, the Patriots won their independence not because they were militarily strong or ideologically committed but because they were weak and unimportant.

Liberty Is Sweet takes us through to the mid-1790s, but its final section reads more like an afterthought than a fully integrated part of the story. These 60 pages, of a nearly 600-page book, cover the economic devastation that immediately followed the war; the Constitutional Convention that in large part sought to rectify that problem; and the new federal government’s final wars against its own revolting citizens and Western Indigenous nations, who had not given up the fight. Rather than offer a novel take on what the American Revolution all added up to, Holton summarizes what is for many academic historians today a commonly held position: Not much changed. For most Americans, whether rich or poor, Black or white, male or female, their status remained largely the same. Only for Native Americans was the Patriots’ victory a total disaster.

That is not to say that the revolution’s egalitarian potential was entirely unrealized. Holton concedes as much but emphasizes that the most democratic reforms happened at the state, not federal, level. Several state constitutions written during the war made it easier for common white men—and in New Jersey, wealthy white women—to vote, and most Northern states began to phase out slavery. But the federal Constitution snuffed out whatever democratic impulses some state governments harnessed. It seized enormous power from state governments. It allowed white male citizens to directly elect only one of the four main houses of governance (the House of Representatives). And it strengthened slavery throughout the nation—through the three-fifths clause, which gave slaveholders disproportionate representation in the House and Electoral College; the fugitive slave clause, which allowed slaveholders to retrieve enslaved people who escaped to Northern states; by authorizing the federal government to help suppress slave rebellions; and by allowing the Atlantic slave trade to continue for at least another 20 years.

By ending his account in 1795, Holton brings his story full circle. That year, the federal government found itself, ironically, in exactly the position the British government had found itself in 40 years earlier. Its own citizens had recently waged a revolt against the federal government’s tax on whiskey; meanwhile, George Washington was still engaging in a military battle for Indigenous lands, fighting against an alliance of Indian nations in the Ohio River Valley, this time led by the Shawnee leader Weyapiersenwah (Blue Jacket) and Miami leader Michikinikwa (Little Turtle). The only difference now was that Washington’s army won, forcing several Indigenous nations to cede millions of acres to the U.S.—and to men like Washington, who finally held full possession of the 52,000 acres of Indigenous land he had spent a lifetime pursuing.

Holton has set himself an admirable challenge. He wants to bring together all the recent scholarship on the American Revolution and present it in an engaging, accessible style for the general public. Despite decades of scholarship, including his own, that has challenged triumphalist narratives of the nation’s founding, there are still relatively few mainstream histories that bring all these multiple pieces together. The best of them do not simply summarize what others have said in bits and pieces: They push the scholarship forward by offering a bold new interpretation.

In this regard, Liberty Is Sweet underwhelms. It demonstrates Holton’s enviable grasp of the scholarship and his skill at narrative prose, but it offers no larger argument, only a myriad of smaller rejoinders to popular myths. It is full of interests but no big ideas. One senses that he is giving us a souped-up version of his college lectures rather than a fully thought-through narrative history. Indeed, it is the very familiarity of his story—its conventionality to anyone who has sat through a college U.S. history course in the past few decades—that makes the criticism that Holton received in the run-up to the publication of Liberty Is Sweet both strange and unsurprising.

Strange because his socialist critics

insisted that, based on his Washington Post piece, he was reducing

the revolutionary war to racist backlash in defense of slavery—something that

the book carefully avoids. Socialists should in fact find much to admire in the

attention he gives to the moneyed elite’s attempts to undermine the working

poor’s calls for more freedom. Meanwhile, the scholars who critiqued Holton for

similarly overplaying slavery’s role in the Patriots’ cause will also find a considerably

more complicated tale.

But the vitriol is as also unsurprising. His argument that many white Patriots, especially Southern ones, were partly motivated to break away from Britain in response to acts like Dunmore’s Proclamation would have been, only a few years ago, hardly contested. It is an argument so widely accepted among historians today that, when a writer trots it out in public these days, the best a critic can do is find a minor error or overstatement to undermine its basic truth. In this sense, the intense criticism Holton has already received says far less about the novelty or provocativeness of his arguments than it does about the times in which he is making them. In another era, Liberty Is Sweet would have been an unremarkable book. But these days, it will perhaps inevitably be met with rage.