When Mike Bush was 12, all knees and soft eyes, he won a scholarship to attend youth classes at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. It was the summer of 1968, hot and angry and hopeful, and while it would end with young anti-war protesters getting beaten with billy clubs by Chicago Police at the Democratic National Convention downtown, it began with Mike, a young Black aspiring artist from the Wild Hundreds by way of Memphis, slinging his bag of paper and pencils over his shoulder and stepping out into the sun.

“105th and Moore, to 111th and Michigan. Thirty-four [bus] from Michigan to 95th, 95th to Adams and Wabash,” Mike recites to me 53 years later. From there, he’d walk one block due east, the promise of the Art Institute’s tall columns and Lake Michigan’s cool waters pulling him home. Mike has lived in the Ewing Annex Hotel, located in the South Loop, for the last 24 years, working as the manager for 22. It’s the last of Chicago’s men’s-only hotels, left over from an earlier era in an earlier century when meatpacking and manufacturing were the city’s golden coin of promise, and hotels like this were a common way for men, single and attached alike, to live on the cheap as they saved up for an apartment of their own or sent their wages back to their country families. In this century, it’s the final refuge for many of the 200-plus men who live there now, between themselves and homelessness, where small rooms—sometimes called cubicles and sometimes called cages—rent for $19 a night and where many, like Mike, live for decades of their lives.

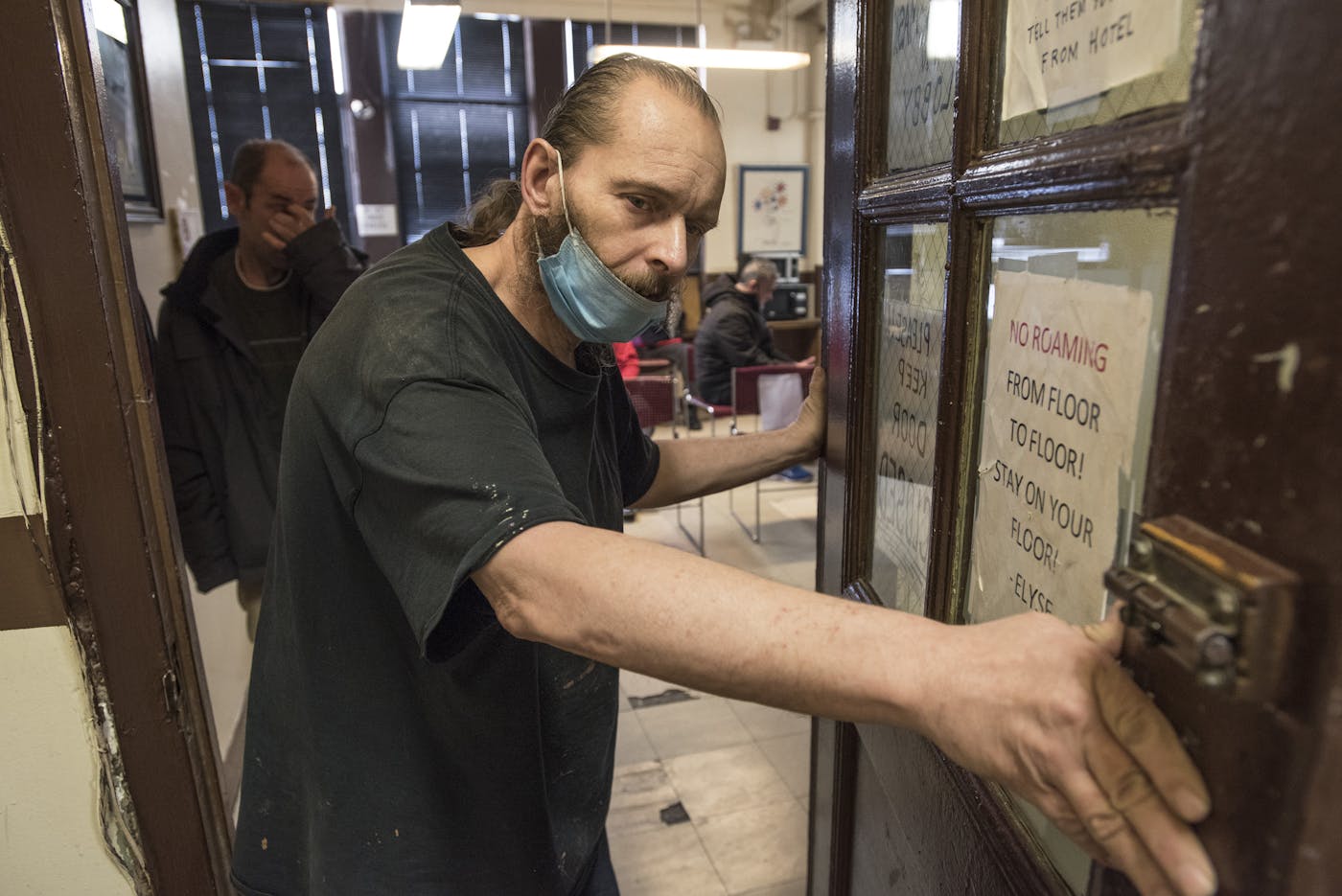

A single stairwell lit by fluorescent lights runs from the ground floor on up to the fourth, linking the hotel’s two wings like a spine. To choose your wing, your room, and your future, you must first open the thin glass door that’s sandwiched between Coco’s Fried Lobster and a nameless party store advertising scratch-offs and Bud Light. Follow the stairs to a landing where Mike, serene in his black zip-up and mask and lacquered behind Covid-protective glass, greets you. From here, any door besides the lobby requires permission from staff and a buzzer to open if you’re a male resident, or the buzzer plus the accompaniment of Mike if you’re a woman, like me.

To the right of the stairs are the private rooms, many of them offices until the 1980s, when this wing was purchased and renovated by Wayne and Randy Cohen, two brothers who own the hotel, the pawnshop, and four other businesses on the same block. These rooms range in size from space enough to host a small fridge, a desk, and a guest to just a couple inches wider than the twin bed. In the room of one man I meet, a 66-year-old artist named Louie Albarron, there is no bed—only art he’s made with what he’s found in dumpsters: paintings of the lakefront and La Madonna, jean jackets he’s embroidered with explosive reds and golds, earrings of twisted copper and small spoons that dangle from his ears. A single window shines clear sunlight on his guitar and photos of his ex-wife, her blonde hair piled dreamily on top of her head.

By day, Louis uses the room as his studio; by night, he blows up an air mattress and sleeps on the floor. Other rooms contain other wonders: pothos vines trailing out of water-filled jam jars; carefully constructed miniature trains lined up on tiny tracks; a family of black and brown belts, still pinned with their security tags, that slink over the backs of chairs like snakes. Some of the rooms on this side have windows; some do not. The price ranges from $400 a month to $450, with the higher end providing air conditioners and, perhaps, a sink. It’s quieter in this wing, where only five men live on each floor and where all the rooms have ceilings.

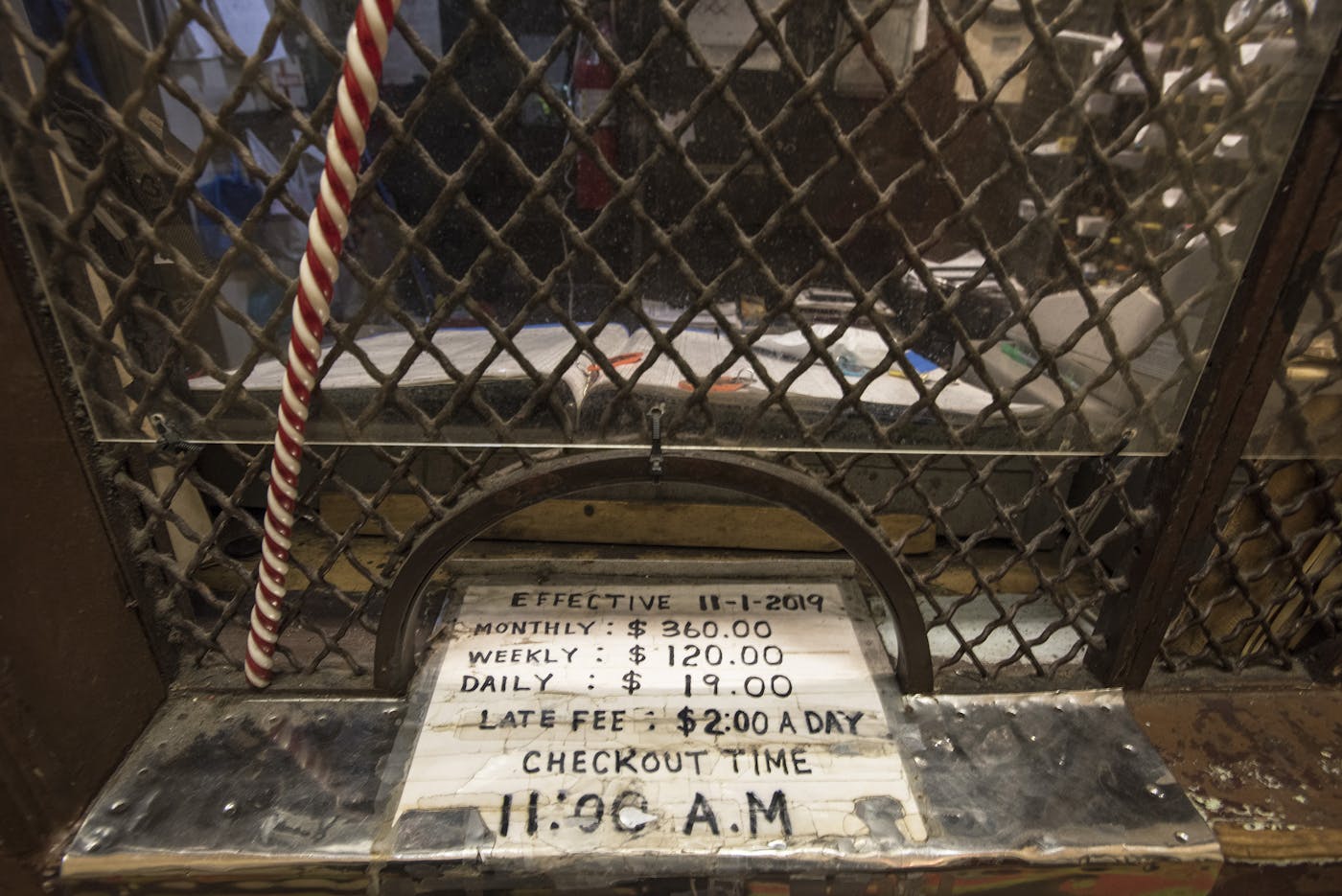

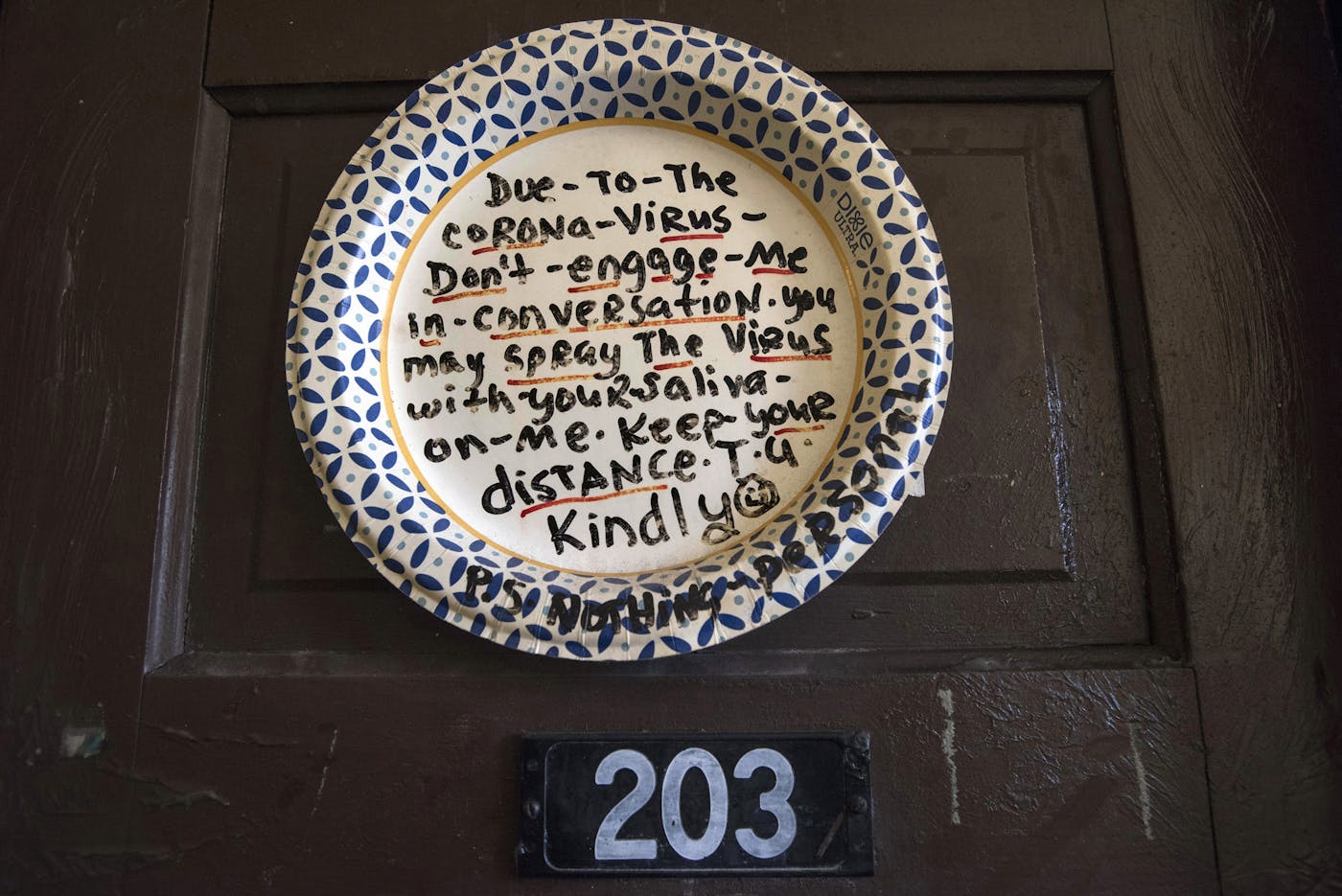

To the left of the stairwell is the original hotel, the part that began as The Workingman’s Exchange. On this side you find wood floors, not tile, and narrow hallways, not wide. Two men can’t pass each other without at least one turning sideways. Each floor holds 54 of the famous cubicles; each cubicle, for $19 a night, $120 a week, or $360 a month, provides a door that locks, an outlet that works, a twin-sized bed with a sheet, and a ceiling of chicken wire that lets your neighbor’s conversations, odors, and dust drift through—hence the “cage” nickname. A century of graffiti painted over in brown and cream still glimmers through, and the new additions shine outright: “Christ is life” and “Don’t knock on this door unless you got a pussy.” Pictures of foreign cities cut from magazines are taped to one door, sunflowers on another. There’s no air conditioning here, though the windows at each floor’s end are frequently open and the whir of steel fans encourages the hot, heavy air to flow.

Mike lives in the quieter wing as does his son Demetrius, handsome with his father’s quiet manners and slow smile, who, now that he’s out of prison, is leaving the hotel soon to pursue a career as a personal assistant for people with disabilities. He stayed longer than he planned to help his dad, something Mike regrets now. “I feel like I’m kind of holding him back from what he wanted,” he tells me. I’ve never seen Mike’s room, which he lives in as part of his wages, but I know that these days, a friend in Englewood stores Mike’s artwork because his room is too small for most of his paintings, his drawings, and the found materials he wants to turn into large-scale sculptures. This friend touches the paint up and mows the lawn of every unoccupied home on his block. He uses solar light to power his home and a few of the others. Mike loves that this friend cares enough about the empty homes in his neighborhood to tend to their possibility, to work toward a future in which they’re homes again.

Like his friend and like his son, Mike strongly believes in caring for what and who are already here. In every one of the many conversations we have from May 2020 to February 2021, he shares with me, in his quiet, passionate voice, his vision: shuttered schools across the south and west sides remodeled, their doors opening like petals for women and children fleeing violent homes or for other Chicagoans in need of shelter while they wait for housing vouchers to come through, classrooms converted to dormitories, cafeterias serving whoever needs to eat. With his words, long dark factories light back up in their second lives as clinics treating substance-use disorders. Other factories are once again noisy, this time with the sounds of job training, or maybe a second life in manufacturing masks and other high-demand health care products. Homes sunk by predatory mortgages could offer daycare or even, with city financial help, become homes again.

Mike’s home is the hotel. On any given day, the same is true for up to 210 men, some of whom stay for a night and vanish, some of whom check in and out and in again, and others who have lived there for decades. They are as old as 86 and as young as 18. At the front desk, they show driver’s licenses, state IDs, and passports. They were born in Cicero, they were born in Ghana, they were born on a table in Cabrini-Green. They work as substitute teachers, as security guards, as dishwashers, as panhandlers, as personal aides. They’re retired. Some are veterans, others former competitive swimmers. Many have been to jail. To stay alive, many rely on daily medications: for their heart, their blood pressure, the mental illnesses that make it difficult for them to distinguish reality from hallucination, threat from friend.

For 22 years, Mike has arbitrated fights, administered Narcan, arranged flu clinics and holiday meals, coaxed residents into taking their meds, connected those looking to outside housing, and, for some, made sure their bodies were properly cared for after being carried out the door. This year, he’s leaving.

The Workingman’s Exchange was built in the 1890s to make money and meet a need. Men needed cheap housing, and Alderman Michael Kenna needed their votes. Before his rise to City Council, he worked as a committeeman churning out votes for the city’s infamous Democratic machine. While Kenna didn’t run the hotel, he did run its adjoining saloon, nicknamed “The Hinky Dink,” a nod to the powerful Kenna’s slight height. “This was Kenna’s ‘philanthropic’ saloon,” Chicago’s first historian emeritus Tim Samuelson wrote to me, “offering huge, inexpensive glasses of beer and free lunch for the working poor of the area.”

The men of the Exchange were hungry and eager, with sweethearts they were moving toward or families they were fleeing, with the promise of a job but little money in their pockets or small fortunes and a desire to disappear. They spoke English, Swedish, Cantonese. They came from all over the country, they took boats across oceans, they hopped a train from Indiana, and they ended up here, at 426 S. Clark Street.

Like their historical brothers, the men of the hotel today are racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse. In a city notorious for housing segregation, the hotel is “the United Nations of Poor People,” laughs Mike. And, like in the past, there are rumors of idiosyncratic millionaires or the fallen rich living here from time to time. In 1946, the Chicago Tribune reported that after a man died in the cubicle he’d lived in for years, detectives doing a routine search of his room found $40,000 in bonds (worth over half a million dollars today), bits of bread and cheese, and a large box of cigarette stubs with traces of lipstick on their ends. Mike says two Enron executives flashed their work IDs when he asked for identification during their stay in late 2001.

The Ewing Annex Hotel exists today in a weird blurry space; beds are advertised for men in transition, but many residents stay for years. It’s a hotel that asks if you’ve been incarcerated in the last six months during check-in, a home where the front door to your building doesn’t lock and where you drop off your keys to your room at the front desk every time you leave. It’s a four-story building without elevators that rents to many with disabilities, including those who use crutches and wheelchairs, and those who are amputees.

In his two decades on the job, the number of elderly, disabled, or ill residents has increased so much that Mike has a collection of abandoned walkers and wheelchairs piled three high in the crawlspace above one of the lobby’s vending machines.

On one day I visit, Mike is on the phone with a resident recovering in the hospital from heart surgery. “Some of the equipment he’s gonna need outside of the hospital is too much for the normal size room even,” he explains to me. The man is adamant. He doesn’t want to go to a nursing home, which, to him, represents poor care and certain decline till death. He wants to return to the hotel.

The second time I meet Bob Boardman, he doesn’t remember the first. It’s May 2020. I’m at the hotel, with photographer Lloyd DeGrane, to talk to him for a story we’re working on about opioid users who’ve had access to their drugs or medications cut off by the early shutdowns of Covid-19.

Bob is white, 65, and wears great jackets and layers outrageous sweaters on his thin frame. He nearly always has a bandana around his long, gray-yellow hair and looks like an anti-war hippie but with no middle-class pretense and not all peace. He carries two doses of Narcan at all times. He’s a good listener and a good conversationalist, though his laugh sometimes has an edge to it. The pupils in his blue eyes are shrunken sometimes, the way a younger brother of mine’s are when he’s relapsed. Bob also has an older sister. “She worries to death,” he says, tiredly. That’s why they talk, depending on how his phone is holding up, about once a week. When needed, she helps pay his rent.

Bob’s lived on the streets since he started running away from home as a kid, and he first went to jail when he was 15. He’s the one who told me the cubicles are the same size as the single cells at Stateville Prison. “Which I know,” he says, grinning wildly the first time we meet, “’cause I’ve been a bad, bad boy.” He runs with a younger white man named Jason, who stays in a small garden off of Congress near the busiest fire station in Chicago. We take a walk to go visit him and find Jason listening to music from a small radio and carefully cutting his own hair while eyeing a mirror he has balanced on a rock. All around us, lilac petals drift down.

Bob has lived at the hotel, on and off, for 20 years. He calls it a flophouse, an “old-fashioned 1960s dive.” “They used to have a lot of them,” he tells me, “they” meaning the city. “And they’re necessary, they still are. But they shut ’em down.” If the hotel didn’t exist, Bob tells me, he’d be back out on the street, with Jason in his park, building careful shelters on the nights when the falling petals switched to rain or snow. But the park’s been sold by the owners and will be a parking lot soon.

Bob likes the rent, understood by the men to be the lowest in the city, and after years of sleeping outdoors, he likes being out of the weather. When he’s not panhandling, he reads one of the many books the hotel has, donated by do-gooders or left behind after another man moved out. He likes adventures, crime stories, and spy novels. There’s no washing machine, so once a week, Bob takes a bucket and washes his clothes by hand. “As bad as the conditions are over there, you can kick back, relax, grab a book. You can read there for a while, block out the noise,” he says. “I’m good at that.”

When we talk, it’s been a year since bad drugs caused Bob to, as he puts it, flip out. “I went to the nuthouse for five days,” he says somberly. “This was like a hallucinogenic. I didn’t know. I haven’t had anything like that since ’71.” When Bob returned to the Ewing, he was late on rent. A year later, he’s still late and planning on using his stimulus check to catch up, plus buy a little something for himself. During his stay at the hospital, Bob told his doctors he was prescribed methadone, an opioid-dependency treatment drug, but they couldn’t get his prescription cleared in time to maintain his regimen. He went through withdrawal there in the bed. It wasn’t nearly as bad as when, a few years back, he went through withdrawal in prison. Knowing what was coming, he asked prison staff for methadone. “We don’t have that,” Bob says he was told. And so he just balled up in the bed and, once released, began using again.

The hotel is full of many men like Bob who, after surgery or rehab or in-patient treatment for mental illness, return. As he says, “I have nowhere else to go.”

Mike does everything he can to avoid calling the police. “Save tax dollars and their time,” he explains to me one day in mid-February, breath condensing in our masks. Out of every ten calls he does make to the cops, Mike estimates that five are related to a mental health crisis. While Mike says that many cops he interacts with show restraint and patience, other times, “A lot of them don’t know how to handle that situation. It’s not always pulling a billy club and taser out all the time. Sometimes it’s just a matter of talking to the person.” And so at first, he tries to de-escalate the situation himself with calm words and clear directions. If that doesn’t work, he has handcuffs. Handcuffs? “Yeah, I do,” he laughs. “Couple cases, I had to actually handcuff ’em to the radiators.” I ask him how he got the handcuffs, but his answer is murky: He says he found them, and he “always had a key.” Regardless of their origin, Mike is grateful they exist. “One day, I had to use them,” he tells me. “And thank god I [did], ’cause the guy was actually trying to jump out the window on me.” After being tackled, the man fought so hard that “I was getting ready to lose the fight, so my only recourse was to cuff him to the radiator.” Soon, an ambulance came, and the man was released from the radiator and taken to the hospital.

During every hotel check-in, residents-to-be are asked if they take any medication and, if so, what kind. Their answers are carefully recorded on sheets of paper Mike can refer to “in case somethin’ happens and the paramedics get there.” Mike notices when they’re not taking it, too. A few times, he tells me, he’s had to ask people to leave when the time they’ve paid for is up, “because of their behavior, getting aggressive, not taking their meds.” Over the years, Mike’s had men return and promise to stay on their meds. They show him bottles. “‘I’m taking it now, I’m alright.’” In that case, Mike says, “I give ’em a second chance.” This man Mike cuffed to the radiator, though, didn’t come back, he tells me.

One day in June, not long after Mayor Lightfoot’s decision to raise downtown bridges during Black Lives Matter protests led to police kicking, punching, and shoving protesters on Wabash Bridge, I bike to the hotel. The day is hot and bright, but the sunlight doesn’t glint off the glass windows I pass—they’re all boarded up. After locking up and nodding to the men smoking nearby, I head up the stairs, where I meet Lloyd at the desk. Mike is elsewhere in the hotel, putting out fires metaphorical or real, and Nelson is covering for him, so he’s who I hang with after Lloyd is buzzed in the stairwell door to go rouse Bob.

“Are you okay?” Nelson asks me. “I heard you sneeze.” I assure him that I’m fine—no Covid, just dust. He glances at my mask. “Try not to get the disposable ones,” he advises me. Nelson favors cloth masks he can wash every day, but he really wants one he saw a commercial for on the lobby’s endless TV. “It’s beautiful,” he tells me enthusiastically–black, $29 or less, with copper in it. “The copper, if you get sick inside, it heals you. And if anything touches you, you’ll still be healing.”

Nelson is 58 years old and white, with short hair, an earnest face, and movements that remind me of a rooster. A resident interrupts our conversation to check his mail. Nelson helps him, then starts talking again, only now, the subject has changed: “But you know, one of my best friends went into my room. ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ I mean, nobody’s ever, in twenty, twenty-five years, no one’s ever gone in my room while I was sleeping.” Like Mike, Nelson lives at the hotel.

Recently the guy in the cubicle next door to him died. “Russian guy,” Nelson says. “Always taking his medication with that booze like it was water. He fell between the bed and the stand.” His friend, I realize Nelson is telling me, came into his room to check on him, worried that it was Nelson’s body who had made that thump.

Nelson says he always carries Narcan and always wears gloves. He’s one of four or five clerks who work the hotel desk in shifts. He grew up in Rogers Park without biological family, moving through five different foster homes across the city until the age of 21. After that, he was on his own. “All I used to do is swim,” he tells me, and laughs a little at the memory. “Thousands and thousands of miles. And I won a lot of gold medals.” Fake gold, he assures, me, handed out by park district staff. “But man, I just had a stack of ’em, like Mark Spitz, you know? I was just taking it all.” One day, his apartment got robbed. Gone were the medals he’d carefully brought with him through every move. Later, he saw them in a pawn shop. “I said to myself, how much they give you, a dollar? I said, man I earned those. I really earned those.”

Despite growing up in The Great Lakes State, I didn’t learn how to swim until I was nearly 30. When I go home, I look Mark Spitz up. I learn about his cheeky mustache, his nine Olympic golds, his perfect white teeth. Nelson would’ve been ten in 1972, the summer Spitz won seven gold medals and set a world record with each. I like to imagine Nelson diving into a city pool, feeling his body slice through the water, his triumph golden and real.

Sometime in the ’80s, after moving around the south side throughout his teens, Mike left high school for Uptown, where he lived alone. He wanted to get away from crime and from the police harassment that came with living in a neighborhood associated with crime. But, as he says, “I jumped right into the frying pan up there.” On his way to the train, people would offer him drugs; on his way back, cops would stop him. “‘Hey, you,’” Mike says, sticking out his chest and deepening his voice. “‘Come here.’ Jump out of a car on you. I thought I was leaving that, when I left Woodlawn. I thought I was leaving that behind.”

Mike took a job working for an adult bookstore that also sold sex toys. The company required employees to periodically rotate to locations across the city. On the day Mike was arrested, he was working at the shop on the corner of Irving Park and Sheridan, talking to a man who stopped by to chat every other day on his way home, the man told him, from work. He didn’t know it, but the man was using their conversations as cover—he actually sold drugs outside of the shop.

Swept up in the raid was another shop regular, a sex worker who sometimes asked Mike if he could front her a couple of condoms until she made some money. When she told the police Mike sold her the drugs they found her with, he believes she was protecting herself then, too, by not turning on the man who was her actual supplier.

“So they kept searching me. ‘Where’s the money? Where’s the money?’” Mike’s voice grows deeper, louder, his shoulders thrusting out as he imitates the cops of his memory. “What money?” he continues in his normal tone. “What happened was, she came in and asked me for change from a bill that they gave.”

He was arrested on the spot. While locked up, Mike says the state’s attorney kept pressuring him to plead out. “‘Well, if you don’t sign these papers to agree on this,’” Mike recounts, “‘then you gonna wind up getting thirty years.’ And I’m—I’ve never been in trouble before, so I’m scared for my life, you know? Thirty years? I’m in my thirties now! You know what I’m saying?” And so Mike pled guilty to something he says he didn’t do. In exchange, he served three years probation. “I even lost a job because I didn’t put that down [on my application] at the time,” he tells me now, in the lobby of the hotel. Recently, he heard some senior housing won’t admit residents with a felony on their record. He’s worried.

“Do you think you will fight it now?” I ask.

Mike nods. “Yeah,” he says, “Imma have to. Before I leave—”

“Chicago,” I interrupt, thinking of his upcoming move south.

But Mike continues: “—this earth. Because I don’t want to die with that on my name. I didn’t do that. I didn’t do that. I didn’t do that.”

The sound of floor fans hum here year round; the TV in the lobby is always on, always loud. The lobby smells like whatever was microwaved last. In the winter when I come home from the hotel, my coat and hair smell like cigarettes, even though no one I interviewed indoors was smoking. The aroma, seeping out of the walls like an invisible fog, is stronger when it rains.

I do most of my interviews in this lobby, crisscross from a donations table where church groups and other organizations drop off clothes and packaged food and where hotel staff puts goods salvaged from cleaning out rooms after residents leave. Decades of handmade and printed signs are taped or nailed up–for veterans’ help hotlines, information about free meals in the city, a chicken curry special from the Indian restaurant a few storefronts down.

The third or fourth time I’m here, Wesley Duran comes out from behind the desk with a clear plastic trash bag. He spreads it out like a picnic blanket, wrists snapping, over one half of my table, securing the edges with clear tape. He leaves, returns with another bag, repeats the routine. He does my chair next, slipping a third bag over the rough plastic. He does this as an added layer of protection from the coronavirus, which has yet to rip through the hotel. “When you’re having guests,” he says when I thank him, “you wanna keep the place clean, you know? You wanna put the good china out.”

Wesley works his ass off. Everyone who works at the hotel does, but Wesley–or Wes–tends to be working the shifts I drop by, so I see him most often: hustling to mop the bathroom, giving returning residents their keys to their rooms when a clerk needs to step out, offering me an orange pop from the vending machine and refusing my money for it. I’m not sure what his exact title is. He’s white, wears a thin ponytail, and favors baggy T-shirts.

Wes is from Cicero. “I grew up on very strong fundamental groundwork in loyalty, in being someone you can count on,” he says. He moved into the hotel in 2006. He’s an avid reader and a studier of philosophy, and he’s deeply suspicious of cable news. Wes loves that I’m a writer. Like Nelson, like at least half a dozen other men I meet over the course of the year, for the majority of his adult life, Wes’s career was delivering the paper.

“I’ve got thirty-three years between the Tribune and the Sun-Times,” he tells me. Thousands on thousands of days loading up trucks and riding out in the predawn dark to make sure the rest of the city had the day’s news to read over their coffee or on their commute. “That had purpose,” he says. “I had a point.” When he started at the Tribune, Wesley says there were eight unions. He liked working at a place with such collective strength.

He lost his job on October 18, 2010, when the Sun-Times merged delivery services with the Tribune. These days, there’s no Tribune trucks rolling, either; both papers have switched to independent contract drivers.

“When someone moves, Wesley cleans the room, he scrubs it down, he burns what has to be burned,” Bob says, including torching floorboards and baseboards. “He’ll spray, but he can only do so much. He’s one person. It’s a big turnover.” He drags on his cigarette, looks somber. “I feel sorry for the guy. I used to tell him, ‘Man, they doggin’ you.’ And they do. ‘Get Wesley, get Wesley!’ He’s doing everything. Sometimes, he explodes.”

Mike doesn’t want to be in a position where he’s handcuffing people to radiators to save their lives, to protect his own or other residents’. Mental health services and addiction services rank high on the list of resources he wishes the city provided to his residents, but the list is long, full of items he’s been pushing for years. He wants to install elevators. He wants to repaint the walls. He wants to put in water fountains–with no kitchen, the only water for those in the cubicles comes from bathroom taps.

“Usually during the hot summer, I fill those containers up there with ice water and allow people to sit in here where the air conditioner is. Some people have health issues–they can’t be in the heat. That’s why I was trying to access the TIF funding, to put the air conditioning, industrial air conditioning, in the upper floors. So it would make it more comfortable for the people that live here,” he says.

TIF, or Tax Increment Financing, is a funding tool used by the city to “promote public and private investment” via development. Under state law, an area must meet numerous “blighting factors” for TIF consideration, but the 2018 approval by former Mayor Rahm Emanuel of a $1.3 billion TIF in Lincoln Park—one of the wealthiest and whitest neighborhoods in the city—continues to raise questions about the equity of this process. Several years ago, Mike says he asked the city how to apply for TIF funding for the hotel, but he was told it wasn’t eligible.

The Ewing is not technically an emergency shelter or a congregate living center, even if it frequently functions like one. For example, back in 2005, “The city of Chicago brought and introduced a person that was heading funding for housing for the Hurricane Katrina victims,” Mike says. As he tells it, after that initial official meeting, one survivor was relocated to the Ewing with the understanding that the city would foot his rent for the duration of his six-month stay. “He stayed here, but we never received payment.”

It’s not a mental health services center either, though, according to a survey of the hotel completed by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless in 2013 (the most recent year for which information is available), 25 percent of residents are veterans and 42 percent identify as having a “mental or physical disability.”

During my visits, I met several men who told me that after completing programs at Thresholds, an Illinois nonprofit that supports people with mental illness and substance-use disorders, they were “sent” by Thresholds workers to the hotel. From that point on, they live at the hotel while social workers managing their supplemental security income money come in once a month to pay their rent. Thresholds told me that while they don’t have a “formal relationship” with the Ewing, they do manage rent payments on behalf of some men who live there, who are also enrolled in Thresholds programs, via a process known as representative pay.

“During this pandemic, a lot of these guys work either day labor places or in factory settings where they wasn’t able to go to work,” Mike tells me. Although the CDC moratorium on evictions doesn’t include hotels or motels, no one was evicted from the Ewing. Indeed, resident after resident tell me stories about how at some point during their tenure, they were unable to pay rent for weeks that turned into months, but they were never threatened with eviction. Instead, Mike works out deals with men who need them. If a resident usually pays by the week, for example, when they start making money again, they would resume paying by the week, “plus a couple few dollars toward what they owe.”

Over the years, in an attempt to help his aging, ill residents thrive, Mike has connected regularly with local organizations like The Night Ministry, which provides health care to people who are homeless or in poverty. In 2020, they stopped by twice to administer Covid-19 tests, but he wants more care, and he wants it from the city. Mike’s angry. “We should be able to get somebody to come, a company to come through that specialize in sanitizing hospitals for the virus,” he says. Even though they’re eligible, it would be very difficult for many residents to make an appointment at the United Center, where the city has set up mass vaccinations for eligible residents, let alone to get there and back twice. He wants the health department to come by and vaccinate residents but tells me he’s given up on calling them. For now, The Night Ministry has been able to provide first doses to a handful of men at the hotel.

In 2013, two aldermen tried to shut down every cubicle-style hotel left in the city. One of them, Alderman Brendan Reilly, whose ward borders the Ewing, said, “Average Chicagoans wouldn’t want to house their dogs in this type of facility.” Housing activists, along with the residents of these hotels themselves, pushed back against that language, which they found insulting, and against the closure of their homes without any input from the residents themselves. Mike shows me the handmade T-shirts he and others wore to ensuing City Council meetings and protests. “Please Don’t Make Us Homeless,” they read. Ultimately, the proposed ordinance did not pass, but eight years later, the Ewing Annex Hotel is the last of its kind.

Several men told me that although the Ewing is noisy, at times dirty, and the bedbugs drive them nuts, here they’re able to come and go as they please, with their autonomy and dignity intact. There are no benchmarks to meet, no curfews, no religious services they’re required to attend in order to keep their beds. This is their home; they choose it. In their home, these men deserve, like everyone else, to live safely and well.

Death comes to the hotel unevenly, but it does come. Some years, two men die. Last year, it was eight. They pass from old age or overdose, heart attack or stroke. This is why he asks for emergency contacts during check-in, Mike explains to potential residents. He’s seen too many men buried unclaimed, unmourned, but not alone—in Cook County, unclaimed remains are cremated and buried up to 20 urns per casket—to not try and get a name and number for each resident’s records, just in case.

Several years ago, an 86-year-old named Sid Weinstein called Mike from the hospital and asked him to bring something. He’d lived at the hotel even longer than Mike, and while Mike used to sometimes give him rides back and forth to doctor’s appointments, they weren’t exactly friends. Sid didn’t really have those. Fairly regularly, Mike would be in the lobby, checking someone in and minding his business when the sound of stomping and shouting would drift in through the old floorboards above his head.

“Two old guys, slipping and sliding on the floor,” Mike tells me. He shakes his head, but his eyes are smiling. “One throw a punch and miss, the other throw a punch, he misses.” Each time, Mike would give them a minute of dignity before breaking it up. “Okay. You swung enough, guys?” Panting and glowering, Sid and his neighbor would slink back to their rooms.

A Jewish, white, hot-tempered veteran and a Black artist whose whole life had been a lesson in the necessity of de-escalation for survival, they had little in common but the address they shared. But when Sid called, Mike answered. Mike no longer remembers what it was that Sid asked him to bring to the hospital that day. He only remembers what Sid told him once he was there.

“‘Before you leave the hospital today, I need to talk to you about something. I’m gonna trust you to take care of my business when I pass. Here’s my bank card. There’s enough money to bury me decently,’” Mike recalls. “‘Do that for me,’ Sid said. ‘Whatever is left in the account, I want you to have.’”

Mike knew Jewish burials had to be done a certain way, but he didn’t know what that way was, and Sid died in the hospital before Mike could ask. In between his duties as the hotel manager, he tried to learn. He also wanted Sid to get a military burial, full honors, but he says the V.A. never returned his calls. Finally, the funeral home rang. They couldn’t continue to hold Sid for much longer.

So Mike, the way he’s done countless times before as manager of the Ewing Annex Hotel, made the best decision he could with what he had. He took out a plot for Sid in the military section of the cemetery, thinking that at least then, he’d be among comrades. He picked a nondenominational service. Mike felt bad that time had run out before he could sort out what Jewish rites to follow. He felt worse on the day of Sid’s memorial when, among all the chairs the funeral home staff had set up for mourners to come and pay their respects to this old, fighting man, he mostly sat there alone. “Nobody should have to go like that,” he says.

As Mike sat at the service with his artist’s eye for detail, he paid attention. He noticed the light coming in the windows and how it hit the floor. He watched as a woman with long, gray hair and a fur coat strode in, whispered something to Sid’s casket, and took a seat, where she remained until the memorial’s end. And he saw, once outside after the memorial’s end, the Star of David engraved above the door. It was then that Mike realized: In a previous life, until the mid-twentieth century, it had been a Jewish funeral home.

Mike is really good at his job. He notices detail and cares about people. “Well,” he says quietly after I tell him this, “somebody cared about me at one time.” After the summer of 1968, Mike qualified on scholarship to attend weekend classes at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago for three more years. During those classes, he made sculptures, watercolors, and sketches.

The care Mike takes of the Ewing and the men who call it home is obvious but so is the labor required to, in so many ways, pull it off alone. It’s why he’s quitting, I think, or part of it. He’s excited to leave. He’s excited to pursue his art; to mount an exhibition; to live out a wonderfully boyish dream of living in a repurposed firehouse, sliding down a pole from his bedroom to his art studio every morning; to finally go home to Memphis, the place he’s never quite gotten over. But while avoiding sanctifying him, I don’t know what the hotel is going to be like without him.

In my eyes, the city, and perhaps other institutions with power, have come to rely on the hotel to catch men they otherwise would let fall through. But it’s a reliance based on evasion; as long as they don’t look too closely, they don’t have to do anything about it. When they do look closely, some see a hotel from a nearly bygone area that’s “not fit for dogs” taking up space where high-price condos, and the different clientele they bring, might be. But these men aren’t bygone. They’re still here, in this hotel that some of them hate and some of them love and all of them call their home.

Mike is right, of course, to remind me that it takes no special goodness to pay attention to someone–only effort, repeated, ordinary, every day. It’s also right to note that the fate of hundreds shouldn’t rest on the effort of one, especially not when powerful institutions seem to quietly rely on that one to do their work. Perhaps this effort to pay attention only seems natural to Mike because he’s done it all his life–so much so that it’s become a reflex of his, allowing him to see deeper, look further, walk by empty schools and imagine finally housed families, to look at closed factories and see something life-giving and real underneath the surface of what’s been present all along. The drawing he made and submitted that summer, just shy of 13 years old, when the rest of his life was wide open and waiting to begin? A beautifully rendered, anatomically correct drawing of a human heart.

This story was published in collaboration with the Chicago Reader.