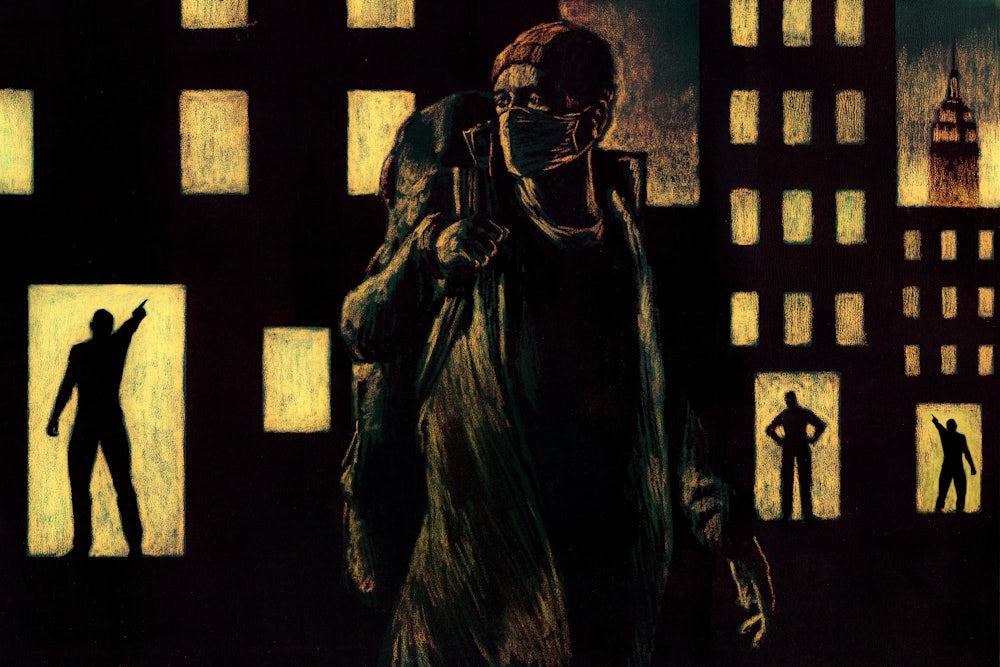

Last March, before the coronavirus was declared an emergency in the state, New York City seemed to be on the cusp of a gorgeous seasonal change. Thousands of hotel rooms across the boroughs had been booked for business trips, spring break sojourns, and weekend holidays. By the end of the month, many of these reservations would be canceled as the streets grew eerily quiet. Faced with bleak economic prospects in the tourism sector and hundreds of vacant hotel rooms, the mayor’s office saw an opportunity. It could move unhoused New Yorkers out of congregate shelters, where people share living space, and into hotels—an action that unhoused New Yorkers and advocates had been demanding for weeks.

In early April, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city would move 6,000 unhoused New Yorkers into hotel rooms. (In reality, this meant the city would be moving 2,500 people into hotel rooms. The figure the mayor cited included 3,500 people who were already living in hotels at the time of his announcement.)

Across the city, around 139 hotels were selected to serve as temporary shelters. One of them was the Lucerne, an imposing, clay-red building on the Upper West Side. The hotel, close to Zabar’s and a block away from the American Museum of Natural History, looms on the corner of West 79th and Amsterdam. The streets and avenues bordering the hotel have served as the charming, affluent setting for Nora Ephron movies: In You’ve Got Mail, Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan drink tea and mochaccinos at Cafe Lalo, just a few blocks from the Lucerne’s steps.

News of the hotel’s repurposing traveled fast: In July, a group of West Side residents and business owners assembled on Facebook, calling themselves “Upper West Siders for Safer Streets.” They intended to protest the move of 283 unhoused men into the neighborhood. The language of safety attempted to conceal, as it often does, the feverish prejudice fueling the project. Comments were racist, derogatory, and encouraged the use of violence against Lucerne residents.

“Maybe if people start being super aggressive and act very violently these vagrants will stop, or at least realize they may get attacked,” a member of the Facebook page wrote. “Kick them in front of a bus if possible.” The New York Post parroted their concerns and interviewed one of their leaders. The group, which soon evolved into a 501(c)4 nonprofit called the West Side Community Organization, opened a GoFundMe and, by the end of August, had raised over $110,000 and hired Randy Mastro, a lawyer who had formerly served as deputy mayor under Rudy Giuliani. Mastro wrote to de Blasio, promising to sue the city if it didn’t provide a timeline for eviction within 48 hours.

The tactic—a threat leveraged by a well-resourced group—worked: Facing a potential legal battle, in early September, the city announced that the residents living in the Lucerne would be evicted. The original plan was to move them to a shelter in Midtown, displacing the unhoused families and individuals with disabilities already living there. (This wouldn’t be the only time the city tried to forcibly relocate unhoused people during the pandemic. It had also threatened to move individuals and families from the Mave Hotel, a boutique operation in a wealthy shopping district, giving them same-day notice to pack up their bags.) After those living at the Midtown shelter protested their eviction, the city decided on a different site for the men of the Lucerne: the Radisson hotel, an imposing stone building just around the corner from the New York Stock Exchange.

Some Lucerne residents were confused by the eviction decision and dreaded being destabilized. Considering the move, resident Travis Trammell asked: “My thing is, I just want to know: for what, though?”

Later, when the relocation of the men was contested in court, a judge would ask the city’s lawyer the same question. Why was the city forcibly relocating the men of the Lucerne? The lawyer would struggle to answer. The decision to move the men into the Upper West Side hotel was made in the heat of the moment, she would claim: an emergency measure intended to save lives while the coronavirus streaked through the city’s shelters. The Lucerne was always meant to be a temporary situation. Now that the city had time to think, to consider, it had hit upon the Radisson as a more suitable location. At the Radisson, the city maintained, the men would be “closer to medical care” and have “more space for on-site services.”

For certain Lucerne residents, this post-hoc justification rang false. They didn’t recognize themselves in the descriptions put forth by posters in “Upper West Siders for Safer Streets.” They felt they already had services and community: They were working, meeting with housing counselors, and reckoning with the pandemic’s effects on their lives. The real reason they were being moved seemed to lie with the protests of their wealthy neighbors and the influence they exerted on the mayor. Yunierki Felix, a Lucerne resident, summarized the issue frankly. “They don’t like Black people around the neighborhood,” he told me. “They don’t like the image of us, of people who have no money, who live in this fancy neighborhood.”

According to NYU’s Furman Center, the median income in the Upper West Side was 91 percent higher than the rest of the city’s in 2018. That same year, the median sale price for a home in the same zip code as the Lucerne was over $1.4 million. Some housed residents of the neighborhood, with its expensive real estate, were worried that the presence of the shelter would drive down property prices. The issue with the Lucerne—like so many issues during the coronavirus pandemic—boiled down to profit over people. “Hotels in the neighborhood are being turned into homeless shelters,” an anonymous poster commented on an article about housing price discounts on the Upper West Side. “It’s no wonder people are fleeing and nobody in their right mind will move here. Covid is the least of the UWS’s problems. Expect more downward pressure on rents and housing prices.” As Zephyr Teachout put it at a press conference last October, the city appeared more amenable to “the demands of a group of people whose primary interest is protecting their property values, not their fellow New Yorkers.”

Less than a week after the de Blasio administration announced the Radisson as the new location, the community board in the Financial District convened a virtual meeting to discuss the move. An official from the Department of Homeless Services, members of the community board, and local legislators were present. During the meeting, Financial District residents raised concerns, many of which mirrored the campaign waged by the West Side Community Organization in its opposition to the residents of the Lucerne. One resident, Christopher Brown, said he was worried about “the integrity of our neighborhood.” He spent his time discussing the proximity of the proposed site to schools and to a plaza where kids play during the day.

This is how residential segregation works, an advocate told me. No one ever says: I don’t want unhoused people living in my neighborhood. They say: I want safer streets. I just want to protect my children. They say: There are schools close to where the proposed shelter will be. As Apoorva Tadepalli wrote recently for The New Republic, it’s rhetoric that frames campaigns of eviction and displacement as prosocial, even loving: “By cloaking the language of profit in the language of safety, these efforts are able to write out the poor and unhoused—those for whom the city is the most hostile and unsafe—from these most basic human identities.” Discrimination is glossed as concern, and advocating for short-term stays is presented as more humane than working with residents to deepen roots.

At the community board meeting, Brown served as a representative of Downtown New Yorkers for Safe Streets, a group that had formed to preemptively pressure the city against moving the men to the Financial District. By early October, the group started fundraising, just as the West Side Community Organization had done. Downtown New Yorkers for Safe Streets also raised a large sum of money: $1 million, nearly 10 times the amount its uptown neighbors had solicited in August. They also hired a lawyer.

A housing specialist I spoke to believed these tactics had ramped up in recent years. And the lawsuits have continued into 2021. In January, a group of landlords, residents, and a restaurant in the Lower East Side sued the city over the use of the Blue Moon Hotel as a shelter for unhoused New Yorkers. This had become the playbook.

How to react to such well-rehearsed motions is up to the city. In the case of the men living in the Lucerne, the de Blasio administration decided it was more convenient to destabilize the residents than to integrate them into the community for the duration of the pandemic. This decision—justified by the uncertain nature of the early days of Covid-19 and the need for ever-shifting measures—is consistent with the shape of New York housing policy writ large. Well before the coronavirus struck, the de Blasio administration privileged short-term fixes over long-term solutions. A year out from the state’s first Covid-19 case, a botched legacy of policy decisions has left unhoused and precariously housed New Yorkers on collapsible ground as they navigate the pandemic and its attendant crises. As the residents of the Lucerne continue to face an uncertain future, the city’s ingrained, historical emphasis on the temporary helps partially explain why secure, permanent housing is unattainable for tens of thousands of New Yorkers.

Back in mid-August, before Mayor de Blasio announced the evictions, Lucerne resident Shams DaBaron noticed chalk decorating the sidewalks around the hotel. The messages were hard to miss—bold lettering, sorbet colors—but he tried his best to ignore them.

DaBaron had been living in the hotel for three weeks. He liked the neighborhood—he knew it well from the decade he’d spent living there in the 1990s and 2000s—and his room in the Lucerne was a welcome change from the shelter space he had shared with 30 others at the start of the pandemic. He was finding his feet, settling in. But the response from neighbors was less friendly than the “Hate Has No Home Here” banners adorning their apartment buildings. So when DaBaron noticed the chalk that August day, he assumed the messages would be trucking in the same Nimbyist rhetoric floating around online. He had no interest in taking note.

One of the hotel security guards urged DaBaron to look closer. In shades of blue, purple, and pink, the messages read: COMPASSION OVER FEAR. Everyone DESERVES a HOME. Stenciled around the edges were pink and yellow hearts. UWS 4 ALL.

The security guard told DaBaron the chalkers were a group of women and their children. They called themselves Open Hearts, and they had formed to welcome their new neighbors to the community. DaBaron found the group’s email on their website and sent them a message. “We, at the Lucerne, need more than that,” DaBaron told them, “if you’re trying to help us.” Open Hearts replied, and the email exchange led to a question: Could he meet with one of the organizers in 10 minutes’ time? DaBaron had plans, but he put them on hold.

He met up with Amanda Fialk, a community resident of 15 years. She asked DaBaron: What can we do? DaBaron told her that he had been pushing for services on-site at the Lucerne since they arrived at the hotel. This was something Fialk, a clinician who has experience treating patients with substance use disorders, said she could help with. In that first meeting, she offered to set up free 12-step groups and AA meetings for any of the new residents who wanted to participate. “I walked away in a daze,” DaBaron said. “I had never seen someone commit to doing good for people experiencing homelessness, like us, so quick.”

After DaBaron’s conversation with Fialk, he and Open Hearts, a core group of around 60 people, began coordinating with the Lucerne’s provider, Project Renewal, and residents of the hotel to design programming. Over the fall, Open Hearts offered the AA meetings Fialk had spoken to DaBaron about; they ran creative writing workshops, art therapy sessions, and life skill seminars. Local faith leaders went on walks with residents three times a week. The Goddard Riverside Community Center, a social services organization primarily located on the Upper West Side, provided $150,000 for a workforce development project that supplied residents with training and wages for jobs.

There were free store events, where clothes, books, toiletries, and accessories were on offer. At one such event—a chilly day that threatened, and soon delivered, rain—members gave out 30 pairs of jeans and emptied two giant cases of socks. Volunteers brought hot coffee and snacks. The prevailing philosophy of the event was that anyone—shelter residents, housed members of the neighborhood—should take what they needed. The group was operating with a mutual aid mindset: The community, through donations, through relationship-building, was caring for one another. It was, as Corinne Low, an Open Hearts co-founder, put it to me, a simple demonstration of “neighbors helping neighbors.”

Project Renewal, a nonprofit organization that serves unhoused New Yorkers, felt the work that the men at the Lucerne and Open Hearts were doing made the site a model, the gold standard for what community integration of a shelter could look like. The residents were taking a situation that was inherently temporary and, through community collaboration, building something that felt stable, supportive. Meanwhile, their property-minded neighbors, those who wanted them out, were promoting a parallel version of events. The offensive comments in the Facebook group continued; the West Side Community Organization threatened to legally pressure the city. The campaign worked. At the end of September, the mayor announced that the residents would be evicted to the Radisson. The date was set for the week of October 19. Buses would be ready to take them downtown.

For some, the situation at the Lucerne is an inflection point: a case study of the city government’s multiple, overlapping failures in homelessness policy. Ruth Messinger, who served as Manhattan borough president in the 1990s, said of the hotel, “This is a story about how the city could do things properly, but too often doesn’t.”

The cornerstone of homelessness policy in New York City is the right to shelter, which was established in August 1981, with the signing of the Callahan v. Carey consent decree. The policy requires the city to provide every eligible New Yorker with a roof to sleep under. While advocates stress that providing shelter for unhoused New Yorkers is a uniquely important and humane commitment, the city’s legal obligation has also meant that a similar level of energy isn’t funneled into housing policy. As Jessica Katz, executive director of the Citizens Housing Planning Council, put it: “The housing agency is not responsible for housing homeless people the same way that the homeless agency is responsible for sheltering homeless people.” In other words, the city is cyclically responding to the crisis of unhoused residents in New York because it is cyclically failing to implement long-term commitments to housing.

This is reflected in the city’s resource allocation. At the beginning of 2020, the City Council totaled the projected housing and services spending for the year. It included contributions from multiple city agencies: the Department of Homeless Services, the Human Resources Administration, Department of Youth and Community Development, and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The total budget, which came to $3.08 billion, included projected rental assistance and rental arrears payments, which help New Yorkers with back rent. Two-thirds of the budget went to shelter spending.

In 2017, the de Blasio administration announced its Turning the Tide on Homelessness plan. The initiative included the creation of 90 new shelters—a move that led critics to conclude de Blasio was more interested in managing the homelessness crisis than solving it. Dr. Deborah Padgett, a professor of homelessness policy at New York University, described the plan as a “huge disappointment.” She told me that the mayor had gradually lost an ability to chart a path out of the crisis “other than the status quo, which is shelters, more shelters.”

The shelter system is legally obligatory, large, entrenched, and expensive. This makes it difficult to change mindsets, to start asking at a wide, systemic level: How do we do things differently? How do we minimize—and eventually eradicate—homelessness and the need for a shelter system of this size?

For de Blasio, the answer seems to be in preventing people from entering the system in the first place. As the Coalition for the Homeless points out, his administration has put forth policies such as rental subsidies and arrears programs that are designed to keep people in their housing situations. But when it comes to helping people out of the shelter system, the city lacks the infrastructure and political will to ensure each New Yorker has a permanent housing solution.

Since the 1970s, the homelessness crisis has been a direct failure of the affordable housing market. During that decade, rents were rising faster than income increases were growing, and the attack on the city’s system of rent stabilization intensified the trend through the 1990s to today. Over the decades, as affordable permanent housing options have shrunk, the number of people experiencing homelessness has increased. (The crisis has disproportionately affected Black New Yorkers: Due to a history of racist housing, education, and criminal justice policies, approximately 58 percent of people living in shelters in 2017 were Black.) Today, for each vacancy in the supportive housing market, there are five approved applicants for a unit. And that’s just the number of people who have applied—there are far more people who haven’t but are still in need. The city’s record on affordable housing provision is equally paltry. Since 2013, there have been more than 25 million applications for 40,000 affordable housing units.

Ostensibly designed to combat this bottleneck, the city’s affordable housing plan, Housing New York, doesn’t do nearly enough for unhoused and extremely low-income New Yorkers—a reality that the mayor himself has acknowledged. The plan was released in 2014, when de Blasio came into office. It promised to build and preserve 200,000 affordable housing units over a decade. In 2017, the administration ramped up the commitment to 300,000 units over 12 years. The plan would create set numbers of housing units for different income bands—from extremely low-income New Yorkers to middle-class New Yorkers—as well as for unhoused people and formerly unhoused and low-income seniors. So far, according to official data from the end of last year, the city has financed 177,971 affordable housing units under the Housing New York plan, but only 8 percent of those units have been set aside for unhoused people.

Josh Goldfein, a lawyer for the Legal Aid Society, connected the mayor’s inadequate housing plan and the plight of the men at the Lucerne. “The reason that we’re even having this conversation again is because the city has failed to put forward an affordable housing plan that matches who needs affordable housing in New York City,” he said.

Larry Thomas, a Lucerne resident, was grimly familiar with this state of affairs. Between entering the shelter system last April and October, Thomas was relocated four times. “I find it real ironic that the mayor can find a way to shuffle us around from hotel to hotel to hotel, like we’re cattle,” he said, “but he can’t find the resources or nothing for us to have affordable housing.”

The reliance on hotel rooms is a decades-old practice in New York. Since the 1960s, commercial hotel rooms have mostly been used to shelter families when there’s no longer room for them in congregate shelter settings. In recent years, however, advocates for unhoused New Yorkers have criticized the practice. The hotel rooms are plagued by a host of problems: They’re costly, displace families from their schools and communities, may present health or safety issues, and often lack kitchenettes, meaning residents can’t cook food during their stay.

Before the pandemic, in 2017, de Blasio had announced that the city was going to cut back on its reliance on commercial hotels for sheltering unhoused New Yorkers. He described hotels as “the last resort,” in line with the administration’s goal to shrink the shelter footprint and save money to invest in upgrading shelters. (The monthly cost of sheltering an individual in a traditional shelter is $3,700. Comparatively, it costs $6,464 to rent a hotel room for an individual per month.) But by April 2020, as Covid-19 cases surged in the city, hotel rooms had become an essential way to get people out of congregate shelters and allow them space to social distance.

That month, de Blasio had promised to move 2,500 people from congregate shelters into hotels by April 20. By that date, the city had moved 1,050 people, which was barely a dent in the number of unhoused people who live in New York. (Some estimates put the number at nearly 80,000.) In April, City Council member Steve Levin introduced legislation that would require the city to move all of its unhoused residents living in congregate shelters and unhoused single adults into hotel rooms as a way to stave off community spread. The de Blasio administration rejected the proposal, claiming it would be too expensive. (The Intercept has reported, however, that the Federal Emergency Management Agency likely could have covered the entire cost of sheltering people in hotels during the coronavirus pandemic.) One advocate I spoke with suspected the city refused to extend the hotel shelter programming for public relations reasons: It didn’t want to deal with the optics of sending such a large number of unhoused people back into the shelter system once the FEMA money ran out.

Regardless of the reason for its reluctance, the past year has shown that the de Blasio administration has the capability to rapidly shelter thousands of people in hotel rooms across the city. For many advocates, this moment has encouraged them to push for more permanent housing solutions. One such option is purchasing hotels the city is currently renting and converting those buildings into affordable or supportive housing—permanent housing that includes on-site services like mental health counseling and employment assistance.

As Eric Rosenbaum, the president and CEO of Project Renewal, the provider for the Lucerne hotel, explained in an op-ed last summer, converting hotels into long-term affordable housing is faster and cheaper than building new units. It’s also something New York has done before. In the first wave of government-funded supportive housing creation, in the 1990s, which resulted in the creation of 3,615 units for unhoused people with mental illness, the buildings bought by the city included rehabbed single-room-occupancy hotels. In midtown, the Times Square Hotel was converted into a 652-unit supportive housing building.

Last summer, the de Blasio administration briefly considered hotel conversion, but, so far, no concrete proposals have been offered. One advocate told me that the purchasing prices of the hotels haven’t bottomed out enough for the city to seriously consider buying and rehabilitating them. (In the first batch of supportive housing, the units had shared kitchens and bathrooms, which would have posed health challenges during the pandemic.) Another told me the city was reluctant to purchase hotels because they were still stuck paying rent on shelter spaces, many of which have multiyear leases. (As the tourism sector inches toward a gradual revival and unhoused individuals will be forced to vacate hotels, the purchase of hotels for housing conversion looks like an increasingly distant prospect.)

In his State of the State address, Governor Andrew Cuomo offered a brief endorsement for converting empty office spaces in Midtown into affordable housing units. The de Blasio administration has said it is “reviewing” the proposal. But while New York flirts with the idea of rehabilitating buildings for housing, California is implementing it. The state has used FEMA money to purchase hotels it was previously using as temporary shelters. In Minnesota, Hennepin County has bought properties it plans to convert, including a motel and a treatment facility, to provide permanent living situations for unhoused people in the county. Other states, such as Washington and Oregon, are considering doing the same. Though these purchases and conversions will only affect a fraction of the country’s unhoused population, the decisions made by these states prove that hotels can become homes if those in power have the political will to make them so.

On October 14, five days before the eviction date set by the de Blasio administration, Downtown New Yorkers sued the city, claiming the shelter would do “irreparable harm” to their community. As part of the suit, they asked for a temporary restraining order, to stop the men being evicted from the Lucerne from moving to their neighborhood. Two days later, the request for the restraining order was denied: The men would still be required to move downtown during the week of October 19. The judge did rule, however, that she would hear arguments for their lawsuit claiming “irreparable harm” starting on November 16.

The web of legal challenges only grew more complex from there: The day before the eviction, DaBaron, Thomas, and Trammell hired a lawyer who successfully filed a motion to intervene in the November case hearing. On the day of their planned eviction, he also obtained a temporary restraining order so that the men would be allowed to stay at the Lucerne for another month before the court case was heard. The yellow school buses, lined up along the side of the hotel, eventually drove away without any passengers on board. The displacement process was temporarily put on hold.

While Lucerne residents were putting energy into fighting their eviction, they were also working jobs and seeking permanent housing. They wanted their next address to be their own, not the Radisson or another bandage solution anywhere else in the city. Thomas, shortly before he went to court, managed to secure an apartment, a one-bedroom that he describes as “spacious, quiet, and comfortable.” It felt like a victorious moment of stability.

Over two days in mid-November, arguments were heard on Zoom court. Four different groups of lawyers were in attendance: those representing the city, the residents of the Lucerne, Downtown New Yorkers, and the West Side Community Organization (who were ultimately denied standing). By the close of the second day, Judge Debra James suspended judgment until the day before Thanksgiving, when it was announced that she didn’t have jurisdiction in the case and dismissed it. The men, it was decided, would be forced to move downtown, whether they wanted to or not. “The intervening residents have no right to choose their own temporary placements,” Judge James wrote in her decision. The city could continue to move unhoused people around wherever and whenever it pleased. Even during a pandemic. Even when the conditions of their eviction would, almost certainly, be replicated in relocation after relocation. Thomas, speaking in October, said the city treated him “like a pawn,” moved from square to square, neighborhood to neighborhood.

Months before the decision was handed down, Mastro, the lawyer for the West Side Community Organization, had argued that the men needed to stay somewhere less “temporary” than the Lucerne; in arguing that the men could be moved downtown, Judge James called the Radisson a temporary placement. The slippery rhetoric of temporariness, instrumentalized to justify evictions whichever way you turn it, doesn’t describe the length of time unhoused New Yorkers spend in shelter more than it describes the length of time spent in one shelter before being moved to another.

In 2019, Nikita Stewart of The New York Times reported that, for years, city officials had shuffled shelter residents around from facility to facility without consideration for their place of work or where they went to school. Removals were sometimes initiated without an adequate explanation—or without any explanation at all. Keeping unhoused New Yorkers in a constant state of transience feeds the homelessness crisis, creating ever-more temporary disruptions in a situation that, for many, becomes a sustained period of impermanence. The impermanence itself grows increasingly permanent, the temporary increasingly long-term. “I don’t like moving,” an unhoused middle schooler told Stewart, “because I’ve been moving my whole life.”

Determined to avoid another cycle of disruption—“I was never moving to the Radisson,” DaBaron told me, “I would have moved back into the streets”—the lawyer representing DaBaron, Thomas, and Trammell appealed the decision. In early January, a state appeals court ruled that the men would be allowed to stay at the Lucerne for as long as it took for the case to move through the courts. (Those who preferred to leave for the Radisson were also allowed to do so.) In conversation, DaBaron and an Open Hearts member stressed how vital this decision was. The men had taken on the city and been granted a stay; they had won around six more months of stability after a period of being told they would have to move in a matter of days. But it was a win with an expiration date—the decision would come under review again in six months and, even if the stay was extended, the hotel would eventually reopen to tourists. The Lucerne could never be their permanent home.

After the men won their appeal, the West Side Community Organization told the West Side Rag that the ruling gave Lucerne residents a choice and that those who chose to stay would “continue to be in limbo with no certainty as to their permanent residency plan and displaced from vital on-site recovery and medical services.” The group, despite setting off the cycle of displacement, has been consistent in its gauzy statements of “concern” about the well-being of the residents, content to weaponize impermanency as a reason to uproot people seeking its opposite.

These statements often hid tactics that were considerably more sinister. In the early days of the court case, a West Side Community Organization member bought Lucerne residents burner phones, meals, and ride-share trips to facilitate their signing affidavits that attested to a desire to move downtown, as confirmed in the organization member’s own court-filed affidavit. (Two Lucerne residents had previously filed affidavits claiming she had offered them money or food if they submitted documents to the court expressing a wish to move downtown; they said other men in the hotel had been offered the same.)

In March, after DaBaron was able to secure permanent housing, a small studio, he received a knock on his door. He was on the phone with Thomas at the time and, thinking it was an Amazon package he’d been waiting for, rushed to answer. Outside were two men. DaBaron said that the men identified themselves as plumbers, there to check on an emergency leak. There was construction going on outside and, concerned that the workers had hit a pipe, DaBaron said he stepped aside to let them through; the men spent approximately a minute in the bathroom before emerging and asking for confirmation on his name and that he lived in the apartment. He confirmed, they left, and DaBaron didn’t think anything more of it. He went back to chatting with Thomas.

A short time later, DaBaron received a call from his attorney, who told him that the men were actually private investigators hired by the West Side Community Organization to gather proof that DaBaron had a permanent address. As Trammell, Thomas, and DaBaron had all found apartments since the beginning of the legal battle, and were therefore no longer residents of the Lucerne, the West Side Community Organization was attempting to void their appeal. Confirming DaBaron’s address was the proof they needed to make a legal challenge that, they hoped, would ultimately force the 48 remaining residents of the hotel to move to the Radisson. As DaBaron opened the door to the two men, unbeknownst to him, the private investigators captured an image of him inside the residence.

Another private investigator working for the West Side Community Organization, DaBaron also learned, had previously visited his building, encountered his super, showed him a photograph of DaBaron, and inquired whether he lived there. The incidents left DaBaron feeling unsafe in his new home and paranoid while out in the city. The West Side Community Organization had corrupted his sense of personal safety, he said, and recklessly unsettled his life in the place where he had finally found stability. Their statements of “concern” meant nothing.

In early February, DaBaron hosted an online event in which unhoused New Yorkers asked current mayoral candidates about the homelessness policies they would enact if elected. (“Today you’re not talking over us, you’re not talking about us, you’re talking with us,” he told the candidates in his opening remarks.) Near the close of the first half of the forum, the candidates were asked what they thought about the congregate shelter system and what the system would look like under their administration. Each candidate who spoke talked about stepping away from congregate shelter and redirecting focus to the development of permanent housing through purchasing vacant buildings. (One of the pillars of de Blasio’s housing platform during his 2013 mayoral run had been a promise to “unlock vacant properties and direct new revenue to affordable housing.” He described, on his campaign website, the cycle that he would soon become a part of: “For years, the city has treated only the symptoms of homelessness—simply building shelter.”)

Maya Wiley opened her response by saying she had spent a lot of time with the men of the Lucerne and members of Open Hearts. She could see something that the West Side Community Organization had spent the better part of a year trying to erase and deny. “What you’ve established, I think, is a model,” Wiley said, “and that model is not congregate shelter.” It was housing “where you have your own apartment and where the services that are necessary are on-site.” It was a model “where there is a relationship with the community.” Under her administration, she intimated, the future of housing policy would look like what unhoused and housed residents had built together on the Upper West Side.

And yet imagining and implementing an alternative to the current congregate shelter system, firmly rooted and diffuse as it is, will take effort, money, and political spine. It seems unlikely that when the Lucerne legal battle is over, when the remaining residents are moved out of the hotel and the rooms overtaken by the usual flow of tourists, a simple change in administration will fix a system that is steeped in such detrimentally short-term thinking. Unhoused people have been advocating for the city to pivot from a right to shelter to a right to housing for years. So far, politicians have failed to deliver. It remains to be seen whether a new mayor will fare any better.

Still, despite relentless opposition and unprecedented circumstances, a model that was stabilizing, a model that privileged mutual aid, took root on the Upper West Side, if only for a short while. At the mayoral forum, Wiley pointed out that it was the government’s responsibility to foster conversations around such possibilities for community-building and integration practice. Open Hearts and the men of the Lucerne “did it on [their] own,” she said, “but it’s a model that shows what works.”