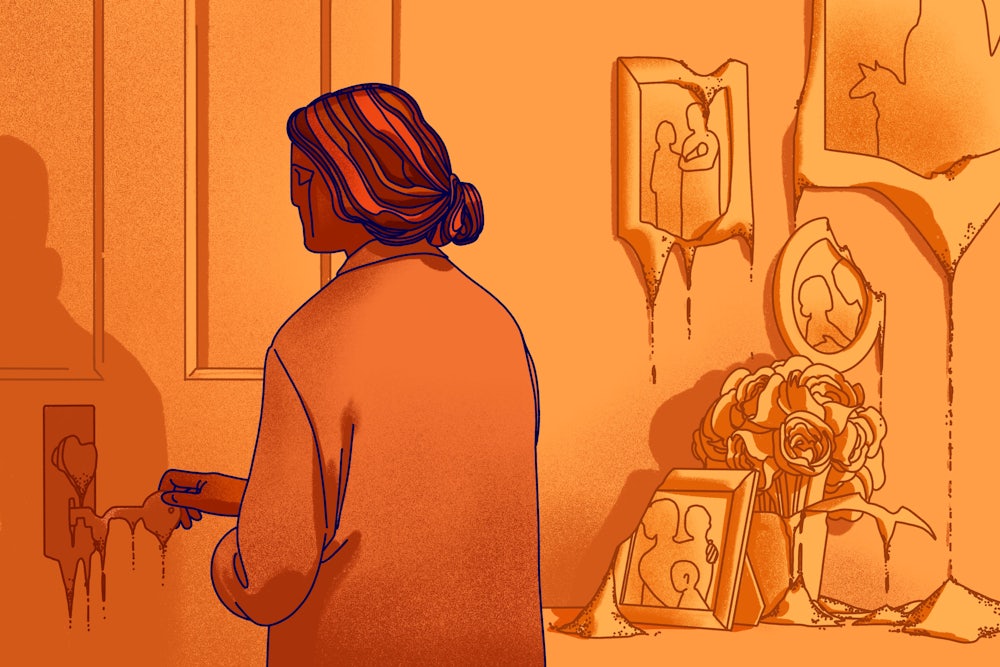

In October of 2018, Leslie Hernandez stood in the hallway of her building, an olive-green stucco and concrete complex in Los Angeles’s Chinatown, trying to communicate with her neighbor Benson Lai, an elder in his early 60s and a monolingual Cantonese speaker. She held up an official notice of a rent increase, which had been given to tenants throughout the building, and tore it in half. Then she took the pieces and tore those too. Lai’s “okay” in response is one origin story for the Hillside Villa Tenants Association. For over two years now, Leslie and more than 60 other households in the Hillside Villa Apartments have been organizing in three languages—English, Spanish, and Cantonese—to reject rent increases of up to 200 percent and stay in their homes. It’s a fight they’d never thought they’d have to take on: For 30 years, their building had been officially designated as Affordable Housing. Though privately owned, Hillside Villa’s 124 apartments were developed through a combination of subsidized loans and tax breaks, tied to a 30-year covenant to keep rents low. But that clock ran out in 2019.

Hillside Villa isn’t unique. Affordable Housing is a policy paradigm encompassing a number of financing strategies, from government grants and subsidized loans to tax breaks, local bonds, density bonuses, and other incentives. To use these benefits, developers are required to temporarily restrict rents on some of what they build, producing what is called “Affordable Housing”: privately owned, publicly subsidized rental housing.

The lion’s share of this housing is constructed through the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC, which helped produce more than three million apartments nationwide from 1987 to 2018. But the total amount of Affordable Housing is difficult to track. States and cities have their own incentive programs, which are often combined within a single development. In 2018, Los Angeles’s budget for Affordable Housing from both federal and state sources exceeded $1.2 billion. L.A. County boasts nearly 120,000 apartments with this designation.

The financing strategies of Affordable Housing constitute the government’s total effort to produce new housing specifically for those who can’t afford market rents. They account for billions in government expenditure and foregone tax revenue. Yet they’ve largely avoided public scrutiny. They seem to skate by on their imprecision, complexity, and branding—who would reject “affordable” housing?—and have largely avoided public scrutiny.

This sleight of hand has consequences. Adela Cortez, a cancer survivor now on disability, has lived in the Hillside Villa Apartments for 34 years, longer than the landlord, Tom Botz, has owned it. If the increase goes through, the cost of her two-bedroom apartment will more than double to $2,450–an increase, for Cortez, which is tantamount to eviction. With doctors and family close by, she told me in Spanish, “I haven’t even given any thought to where I would move, because I love Chinatown…. I’m going to fight to stay.”

“The public-private partnership is the strongest current of federal policymaking” for rental housing, Marques Vestal, incoming assistant professor at University of California, Los Angeles and member of The L.A. Tenants Union (a dues-funded, autonomous union I helped start), explained. In the context of rising tenant militancy and permanent crisis, that history deserves retelling. What’s revealed is a bipartisan pattern by which Affordable Housing is weaponized against public housing, middle-class white tenants are held up against poor Black ones, and real estate—not tenants—become the policy’s ultimate beneficiaries.

Though not yet under the Affordable Housing moniker, 1959 marked the federal government’s first significant use of financial incentives—in this case, below market interest rates—to entice private developers to build rental housing for constituencies they failed to serve: seniors who earned too much to qualify for public housing but too little to rent in the private market. The first programs were limited to nonprofit developers, but over the next few years, for-profit builders lobbied for inclusion and shaped new programs with 1 percent effective interest rates, easy exit strategies, and other beneficial terms. Eligibility expanded, too, to all the “forgotten families,” as President Kennedy called them, of the middle class.

The elderly residents of the Concord Apartments in Pasadena, California, were among the first to live in apartments produced through a system of public subsidy for private ownership. They were also among the first to protest that system. In 1979, the Concord Apartments, a 14-story box tower lined with stout balconies, was purchased by a church foundation started by Reverend William Steuart McBirnie. McBirnie enjoyed a national platform delivering sermons at rallies for arch-conservative Barry Goldwater and was featured in The New York Times as an opponent of California’s Rumford Fair Housing Act, calling the 1963 anti-discrimination law “a giant step into socialism.” (When Tom Botz told Fox 11 the government efforts to protect Hillside Villa made him “feel like [he’s] in Cuba or Venezuela,” he paid tribute to a long tradition.)

Just three years after the sale, McBirnie’s foundation prepaid the subsidized mortgage, moved to auction the building at a significant profit, and demanded more than doubled rents. In response, the Concord’s more than 150 senior tenants launched an affirmative lawsuit against McBirnie, gaining the attention of national news. While few other landlords fit McBirnie’s caricature, early and permanent exit from subsidies was a nationwide problem. A congressional committee on aging even featured Concord elders. “There’s going to be a lot more of us older women…. and we are going to be poorer,” one local activist warned. “I think we all get hung up on the word ‘housing,’ but it means a lot more than a roof and a place to stay for older persons.” A Concord resident pressed, “What [is] the government or the city going to do in order to rescind that sale?”

In 1988, after six years of uncertainty and flip-flopping court decisions, the city of Pasadena bought the land from McBirnie, another foundation bought the building, and the tenants won the right to stay. Only public purchase, not the mechanisms of the market, won long-term affordability and security for residents. Yet national policy failed to prevent their history repeating. Instead, it has followed two central themes: the reduction of federal spending and the devolution of federal authority and resources to cities and states, both increasing reliance on private industry.

In 1973, a Department of Housing and Urban Development-sponsored report noted widespread critiques of past incentive schemes: “Private enterprise was ‘getting rich’ at the expense of low- and moderate-income families.... The subsidies offered were not sufficient and did not aid the families who most needed them.” But that same year, the Nixon administration placed a moratorium on public housing construction, which has more or less proved permanent. A year later, it issued block grants for states to run incentive programs themselves. “We’re getting out of the housing business. Period,” affirmed a HUD deputy assistant secretary in 1985. Privately owned, publicly subsidized production has been the only supply-side policy ever since.

Shaped in turns by inflation, tax revolt, racism, and the red scare, Republican administrations in the ’70s and ’80s invented the housing programs that make up the overwhelming bulk of government response to the housing question today: Section 8 housing vouchers, by which the federal government pays the difference between tenants’ ability and market rent, and the LIHTC, the largest source of Affordable Housing in the country. LIHTC was a last-minute addition to Reagan’s Tax Reform Act of 1986, made famous for slashing the tax rate on the wealthy from 50 to 28 percent. LIHTC issues tax credits to developers, who can sell those credits to the highest bidder, raising capital for a project if they agree to income targeted rents on a percentage of apartments for a limited time—first 15, then since 1990, 30 years.

Unable to run a deficit to pay for social programs and unwilling to tax the rich, a few cities and states inaugurated local Affordable Housing trust funds from 1989 to the early 1990s, bent, like LIHTC, on harnessing private industry. The first large-scale federal law that named “affordable housing” as a specific policy outcome was the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990, further cementing the name “affordable housing” for privately owned, publicly subsidized housing. The bill also initiated the HOPE program—Homeownership and Opportunity for People Everywhere, later renamed Housing and Opportunity for People Everywhere—designed to privatize public housing. In his signatory speech, George H.W. Bush called public housing “a bottomless pit of dependency.”

Of course, the organized abandonment of tenants has been a bipartisan effort. Clinton’s HOPE VI synthesized all prior Affordable Housing trends, slashing funding for public housing and issuing block grants contingent on its destruction and replacement with privately owned, publicly subsidized housing. Rebecca Marchiel, assistant professor of history at the University of Mississippi who also sits on the board of a nonprofit housing developer, highlighted how in replacing public housing with Affordable Housing, policymakers emphasized “balancing budgets with the racial context where it’s assumed, and evidence bears out, that the majority of folks who are living in public housing are Black people in cities.” (The ballooning prison funding under Clinton’s administration suggests that incarceration, not affordable housing, was offered in substitution.)

Throughout the 1990s, tenants of the Pico-Aliso housing projects in Boyle Heights, once the largest housing block west of the Mississippi with about 3,000 residents, organized against the HOPE VI destruction of their homes. One of the for-profit Affordable Housing developers that won a contract at the site now describes that process as a “second chance,” a “turning point” to raise buildings “deteriorated beyond repair.” But residents themselves combated that narrative, leveraging a legal challenge to stall the demolition. Relying on a history of self-organization against gang violence and police abuse, tenants formed La Union de Vecinos de Pico Aliso, staged a series of protests, and pressed for a right of return. As residents and organizers remember, a few tenants even refused to vacate their buildings as bulldozers arrived.

Combined, the $50 million redevelopment of Aliso Village and Pico Gardens created a net loss of housing, removing nearly 600 apartments. The community was not given a second chance–it was removed. “My children were born and raised here,” 20-year resident of Pico-Aliso Manuela Lomelili told The Los Angeles Times. “Even though they say this is a bad area, it hasn’t affected us. I want to live in my community. I love my community.”

“I’m fighting for this because I’ve been here since I was a child,” Hernandez of Hillside Villa told me this March. “I came to this same unit with my parents when I was five years old. I’m thirty-six…. Half of these ladies have known me since I was a child, so to see them hurting hurts me.” With support from The L.A. Tenants Union and Chinatown Community for Equitable Development, the Hillside Villa Tenants Association has been fighting since 2019. Tenants have held a courtyard meeting every Thursday, where trilingual interpretation makes it possible for them to express their fears, build community, plan actions, and strategize. They used clerical errors and emergency anti-gouging laws to stall the rent hikes. When increases actually went into effect in February during the pandemic, many in the association had lost jobs or hours and had already committed to a partial or full rent strike, simply refusing to pay.

Last summer, after a group of tenants staked out his office and itinerary, Los Angeles City Council member Gil Cedillo offered Tom Botz $12.7 million in forgiven debt and payments to extend the building’s rent caps for ten years. But after the two shook hands and a press release circulated, Botz claimed they never had a deal, suggesting to press that the offer was prematurely celebrated and too low. The tenants responded with a visit to Botz’s Malibu mansion. Walking the hills, they shouted chants written by Hillside resident Alejando Gutiérrez: “Hillside Villa is our place, we will not be displaced!” The City Council declared its hands were tied.

This is one of the most urgent problems with Affordable Housing: It expires. Almost a half a million Affordable Housing covenants will expire in the next eight years, including almost 9,000 in Los Angeles, putting up to 20,000 tenants in L.A. county at risk of displacement. As expected, landlords in areas with high or rising rents choose to opt out of incentive programs as soon as they can, displacing the tenants the programs claim to serve. Lawmakers have orchestrated multiple scramble sessions on the topic, yet none have fully prepared for the fallout nor challenged the absurdity of continuing to legislate like tomorrow will never come.

The ticking clock isn’t the only flaw; most housing produced under the Affordable Housing regime is not actually affordable. On top of the building-based subsidies her landlord receives, Hernandez also hands him a Section 8 Voucher, a surprisingly common situation. HUD’s own residency data show that nearly 40 percent of LIHTC housing is occupied by tenants who also receive Section 8 vouchers—though LIHTC itself costs $10.9 billion in foregone taxes revenue each year.

Affordability standards are determined by a HUD calculation of Area Median Income, or AMI, but the “area” isn’t an individual neighborhood; it’s an entire county—allowing a person making up to $63,100 a year in Los Angeles, 80 percent of the AMI, to qualify as “low income.” That is more than double what someone working full time at a $15 minimum wage can earn in a year. Where Hernandez lives in Chinatown, the median income was last recorded at $27,000.

While nearly 11 million tenants–a quarter of the U.S.’s tenant households–qualify as “extremely low income,” earning 30 percent of AMI, and while the median tenant made just $40,500 a year in 2018, the vast majority of Affordable Housing built through all mechanisms targets higher income thresholds. Of the almost 150,000 affordable apartments produced through inclusionary zoning over the years—laws that require a tiny percentage of Affordable Housing in new developments—less than 4 percent were for “extremely low income” tenants. A bias for higher income brackets has only increased over time, as nonprofit developers are increasingly crowded out of contracts. This bias perpetuates racist exclusion from Affordable Housing, as those who least benefit, “extremely low income” tenants, are overwhelmingly people of color.

Isela Gracian, who worked for 16 years at the nonprofit housing developer East Los Angeles Community Corporation, serving the last five as president, affirms the biases of financial incentives. “For some community members [our rents] were still out of reach, especially when we’re talking about folks that are on fixed incomes,” she explained. When putting together the “thousand-piece puzzle” to finance a single project, “the challenge is being able to get more units at the lower income thresholds. That’s largely because in this model of Affordable Housing development, the property ends up, in essence, with a mortgage. These are loans that the developer needs to pay back, so the rents need to be able to sustain that.” Even with Affordable Housing subsidies, the private market cannot meet the needs of the working class and the poor.

That contradiction means Affordable Housing helps accelerate gentrification. In poorer neighborhoods, and those where most residents are people of color, new housing that fails to serve the needs of the existing community will inevitably facilitate the influx of richer, whiter residents. While boosters celebrate the long-term, citywide impact of increasing housing supply, tenants face its immediate, local consequences: an increase in property values means rising rents, landlord harassment, eviction, and the loss of community ties. One stark illustration of this process is tax increment financing, by which resources for Affordable Housing are derived from property values rising in the surrounding community—“affordable housing” funded through its own gentrifying impact.

Often offered as a concession for market-rate development, Affordable Housing is leveraged as a tactic to manage rather than prevent displacement, deflect not incorporate community resistance. “They destroyed one hundred years of history,” Hernandez said of developers and politicians. “Chinatown isn’t Chinatown anymore.” Hernandez narrates the gentrification of her neighborhood as an onslaught against a long-term immigrant community, describing the closure of her favorite shops and restaurants and the displacement of her friends and family in tears. She points to the irony of new Affordable Housing built in her community just as hers expires. “Affordable for who?” she asked. “I don’t get how these politicians, how these people in power could say what affordable is if [they’re] not living in our situation, if [they’re] not walking in our shoes.”

The central beneficiaries of Affordable Housing policy are not tenants but developers and investors—a dynamic affirmed by the revolving door between policy benefits and real estate lobbying efforts. Indeed, one scholar calculated that tenants capture as little as 24 percent of the total value the government hands off in subsidies. Affordable Housing offers temporary relief for tenants but permanent gains for landlords, who receive millions in public funds to lower rents for a time, then reap the profits of market rents—often on what had been public land—in perpetuity. Rather than levy new taxes, incentive schemes entice the rich to park their money temporarily with a promise that it will be returned, exempt from taxes in the meantime. Rife with kickbacks and fraud, the programs also bankroll an industry of financial middle men to match investors with government programs. Within a global finance regime, Affordable Housing aids what David Harvey calls “geobribery,” a fix not for the scarcity of truly affordable housing but the abundance of global capital seeking to land.

Los Angeles now boasts the world’s most expensive home—a $340 million spec mansion complete with five pools, 42 bathrooms, and a moat—while four unhoused tenants die on our streets each day. Nationwide, there are 30 or fewer apartments accessible for every 100 “extremely low income” tenants, and two affordable apartments are lost for every one created each year. Vouchers serve only one quarter of those who qualify, and waitlists for Section 8 or what little public housing remains stretch a decade long. In the meantime, tenants go without food, medication, and basic necessities to keep themselves housed. Vestal of UCLA calls these deaths and indignities “the body count” of “relationships administered under the institution of private property.”

Affordable Housing helps manufacture consensus around more of the same injustice. Gracian of the East Los Angeles Community Corporation describes how the Affordable Housing granting process compels narrow thinking: “How am I going to get the financing to put this credit, how am I going to get it to the finish line…. that’s how [within] the landscape of Affordable Housing, imaginations get so sucked out of a room.” For Marchiel, these limitations came to constrain activists themselves, who began to use “developer-speak” and “parrot back the language that was circulating in public policy debates.”

The strategic myopia of offering technical solutions to political problems, valorizing the expertise of financiers and economists over that of residents, and situating the private real estate market as the cure rather than cause of the housing crisis, is baked into the Affordable Housing project. Rather than resist the community’s exploitation or eviction, Affordable Housing encourages us, as Leonardo Vilchis, supporter of La Union de Vecinos de Pico Aliso and cofounder of the L.A. Tenants Union, often puts it, to “negotiate the terms of the community’s defeat.”

Instead, the tenants of Hillside Villa have offered a radical vision for the future of their building: take it out of the landlord’s hands, so the tenants can take control of their fate. “What do we want?” “Eminent domain!” “When do we want it?” “Now!” On a Saturday night this March, Hillside Villa tenants gathered in front of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, chanting, giving speeches, and projecting slogans onto the iconic building, which had been subsidized with taxpayer funds on land acquired through eminent domain.

Thirty-four years ago, Hillside Villa resident Adela Cortez was ejected from her home in downtown Los Angeles when the city used eminent domain to appropriate the land underneath it to build the Los Angeles Convention Center. She told me that city officials helped her secure an apartment at Hillside Villa, but no one ever told her it would be temporary.

Situating their struggle within a long arc of dispossession in Los Angeles, the tenants of Hillside Villa are demanding the city turn its powers of expropriation, so often used against poor communities of color, to protect them. When Tom Botz rejected the $12.7 million deal, Hillside Villa called for City Council to buy their building and keep it permanently affordable, using eminent domain to force the sale. This February, after another year of protests—many highlighting the vast expenditure of public resources on police—the tenants won a symbolic victory when City Council passed a motion to support the idea. But officials have yet to appropriate the funds, continuing to cite budget shortfalls, dodge meetings with tenants, and pass the buck.

Like all forms of nostalgia, the idea of past public housing as truly dignified policy is an operation of fantasy, a longing for a past that never existed, or was never allowed to exist. Yet the trilingual, multiracial, and multigenerational organizing of Hillside Villa offers a new vision of what public housing could be in service of tenant power and community control. Hernandez told me, “You know, we don’t have any markets around here; we don’t have childcare. We don’t have any place where seniors can just go hang out. We’ve been fighting for a freaking community garden. We want to better our community because we know what we need.”

The Affordable Housing paradigm is not a benign compromise between public and private interests; it is the institutionalization of racism and the red scare, a system bent into shape by the power of real estate not designed to serve tenants’ human needs. Putting expropriation on the table as a policy tool, demanding eminent domain to ensure a permanent right to stay put, the tenants of Hillside Villa have refused to become Affordable Housing’s collateral damage. They encourage us not just to imagine but to organize for a new kind of housing governance–one that enshrines collective stewardship and self-determination, one that doesn’t cajole, beg, or incentivize, but provides. In Adela Cortez’s words, “first our building, then the city.”