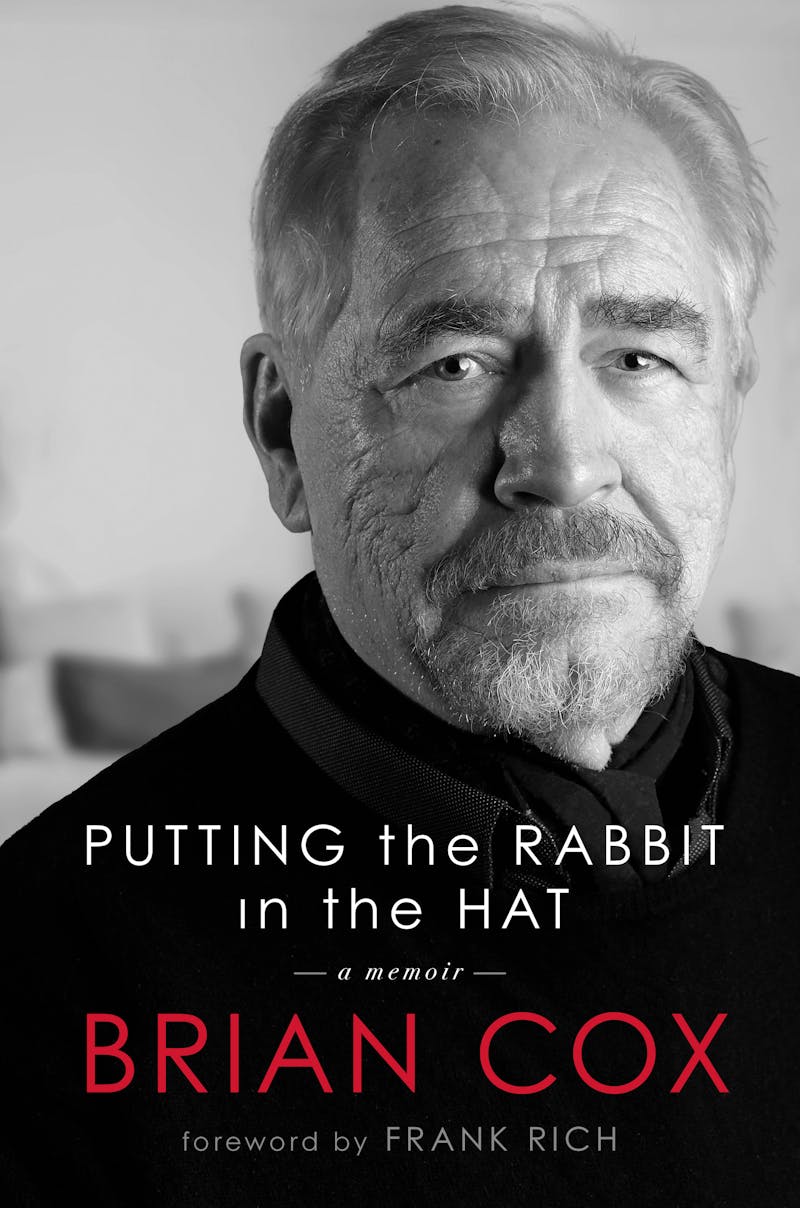

In his memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, Brian Cox recounts making The Boxer, a somewhat treacle-bound 1997 Troubles film set in Northern Ireland. As he has done throughout his entire film career, he played a significant supporting character—a local IRA patriarch whose daughter (Emily Watson) pursues a dangerous romance with boxer Barry McGuigan, played by Daniel Day-Lewis. “Back, then, Daniel was full method, of course,” Cox writes. One day, he and director Jim Sheridan watched Day-Lewis doing his thing. “Skipping. Shadow-boxing. The works.”

“‘You know, Brian,’ mused Jim, ‘I’m just not sure that boxing works as a metaphor for this film.’” Day-Lewis had now “slapped a rolled towel over his shoulders” in authentic style. “I’ll tell you what, Jim,” Cox said, “I think it might be a bit late for that.”

Many outlets have reported on Cox’s book’s indiscretions, including comments about actors like Johnny Depp (“so overrated”) and Ed Norton (“a pain in the arse”), as well as some choice words about his Succession co-star Jeremy Strong in a recent, now-notorious New Yorker profile. By his own report, Cox has received “a lot of flak about disrespecting some and all that.” But he’s not “having a go.” Instead, there’s a thrift to Cox’s remarks, which relates to their meaning. That quality’s in abundance in the Day-Lewis anecdote; the remark is both literally concise and implies that doing too much as an actor is almost antithetical to the whole activity.

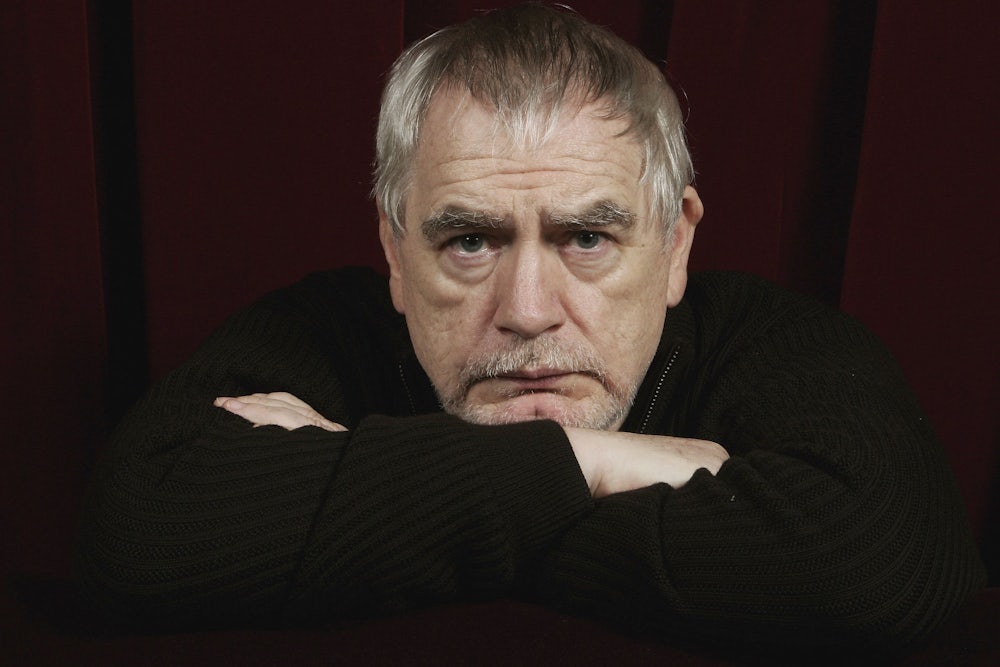

What explains the gruff-meets-bitchy tone of Putting the Rabbit in the Hat? Cox grew up poor in Dundee, Scotland, and is now 75 years old. Being willing to speak directly and with expertise, even or especially when the subject doesn’t want to hear it, is almost a moral tenet of his generation; Cox’s latest flush of fame as the mogul-patriarch Logan Roy on Succession has happened quickly, and perhaps he just hasn’t had the time or the inclination to adjust to the new niceness of public relations.

With his dry wit, down-to-earth, slightly macho vibe, and a technique honed across decades in provincial repertory, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Broadway, and the BBC, Cox is an economical performer and intolerant of profligacy. Like a champion swimmer, he simply has good technique and disapproves of splashing.

The great thing about an artist’s autobiography, or really any nonfiction book about the arts, is that you can put the book down to watch (or listen, whatever) along as you read. In this respect, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat is an exemplary syllabus. As a kid in 1950s Dundee, Cox recalls his father, who died when he was 8, throwing huge Hogmanay parties, at which the young Brian would burst into medleys of Al Jolson songs (not, it is specified, in blackface). His mother was not well, and Cox recounts an education interrupted by long stretches spent in the local cinema and running errands (“messages”) for teachers and others. In one very sweet moment, he describes a note he left for one of his older sisters, who left him to his own devices. “Dear Irene, you’ve never looked after me, you don’t look after me probably [sic]. I’m not going any more messages for you.”

The movies that Cox describes altering his chemistry as a child at the cinema cohere around a sort of passionate, independent masculinity: He describes being overawed by James Dean clunking his head against a tree branch in East of Eden; the slick, working-class macho of Albert Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

The book is written in the style of an “as told to”—a series of reminiscences, expressed in Cox’s own charming Scots idiom, progressing from babyhood to the present day. After his Tiny Tim years, Cox got involved with a local theater in Dundee, which unfortunately burned down but not before the young man had been hooked on the stage. Though he’s a cineaste at heart, his silver screen dreams set alight by Albert Finney’s and Richard Harris’s working-class heroism, the theater brought him into the world of Michael Gambon and Laurence Olivier (Gambon, Cox says, deliberately stepped on Olivier’s cloak during a production at the National Theatre). Of them and of his years in famous productions like Titus Andronicus and Rat in the Skull, he has much to say, and none of it discreet.

Theater isn’t often taped well, so it’s almost peculiar that there’s no way to see the work on which Cox made his name, while his lesser work in film and television is so freely available. His first role in Hollywood probably remains his best: His turn as Hannibal Lecktor in Manhunter is quite different from Anthony Hopkins’s Hannibal Lecter (note the difference in spelling) in the Hannibal films, which he doesn’t think much of. “Tony played him crazy whereas I played him insane,” Cox writes.

Manhunter was beset by distribution problems and didn’t translate into an immediate boom in Cox’s career. Slowly, he became a character actor. You can tell that he’s one of those because he dies in so many of his movies. In The Long Kiss Goodnight, Geena Davis plucks a pistol from the trousers of his drowned corpse. In Rob Roy, he gets it in the throat from Jessica Lange. In Coriolanus, he commits suicide by a depressing canal. The Autopsy of Jane Doe, Troy, Terèse Raquin, X2, The Bourne Supremacy: In each, he’s a goner.

His best roles since Manhunter have been on television, not film. In Deadwood and Succession, he plays male leaders of totally opposing characters, making them brilliant side-by-side viewing. Special mention must go to his valiant performance of Hermann Göring in the otherwise appalling 2000 miniseries Nuremberg, which starred Alec Baldwin as chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson. In much of the rest of his work, and especially in the dross he’ll happily admit to having made for money (The Glimmer Man, a lot of horror movies), he has been harvested for his gravitas in Hollywood, like zest grated off a lemon. He’s a supporter: With the possible exception of Logan Roy, there’s been no leading-man film equivalent to his Titus Andronicus, a stage performance so good that my auntie who saw it in 1987 still talks about it.

Cox has a sort of old-fashioned masculinity that means he gets to have it both ways—to be a gossip and a down-to-earth shopkeeper’s son. In the book, he’s pleasingly horrible, often in ways that are genuinely insightful. But the bluster can all be a bit convenient, especially when it comes to the stickier wickets of his acquaintance.

His excursus on “woke” is lamentable and best passed over quickly. Meanwhile, Woody Allen and Mel Gibson both come in for hearty rounds of endorsement, while he claims grandly and hazily that Harvey Weinstein gave him the creeps. The way he writes interchangeably about his wives and children (he has a passion for “absence,” in his words) is a bit unsettling. It’s in these sleight-of-hand moments, where Coxian acuity might actually be helpful for understanding his place in the culture, that he slips into vagueness.

If the point of the exercise of autobiography is to record the truth as it has felt to one individual, then one that conveys the subject’s failings should be measured a success. A curious product of contrasting times, places, and styles, Cox is a heavyweight who is clearly enjoying his limelight reprise.