A century has passed since Buster Keaton entered the plum decade of his career. Then in his twenties, he had outgrown his family vaudeville act, whose violent acrobatics had relied on a size contrast between father and son, and learned the art and science of making movies from Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, in his studio on 48th Street in Manhattan.

Thus schooled, Keaton began a rampage of comic invention. First came a flurry of now-legendary two-reelers—One Week (1920), Cops (1922)—then his full-length silent picture era, with Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), et al. It’s one of these, Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1927), his last independently produced feature, that contains the most famous of all Keaton’s many stunts.

The young William Canfield Jr. (Keaton) has gotten blown all over town in a thrilling action sequence set during a cyclone. During a brief moment of respite, he wanders a few dazed paces, before stopping. Behind him, the two-ton facade of a house tips, lurches, and then falls on top of him. An empty window frame clears him with only inches to spare, rescuing him from certain death. In one of Keaton’s trademark delayed-reaction routines, our hapless hero seems only mildly astonished as dust clouds rise around him—about the same way he looked when he wound up at a stable surrounded by horses 30 seconds earlier.

It’s a terrifying scene, both to watch now and to film then, but awash in the same kind of adrenaline-soaked magic you also get from watching vintage Jackie Chan (himself a Keaton superfan), or the classic Vine of a honking four-wheeler flying over a house, or the slapstick horror of the #milkcratechallenge on TikTok. It’s a fast-paced, nihilistic kind of absurdity, a form of comedy proudly whittled down for the attention span of a child, and as much reliant on surprise and contrast as on jokes strictly conceived.

We might call it conceptually unsophisticated, at least compared to the movie comedies of someone like Mel Brooks or Woody Allen. But in the 1920s, Keaton’s work in slapstick created a foundation that the whole ensuing business of film entertainment would lean on. Now the Hollywood blockbuster era of film entertainment is arguably over, subsumed into the infinite maw of internet content, and we have entered another era in comedy, a clowning era—one casting Keaton’s influence in a strange new, digital light. Whatever drew us to Buster Keaton’s body a century ago is again at the center of popular entertainment, whether or not we have a name for it.

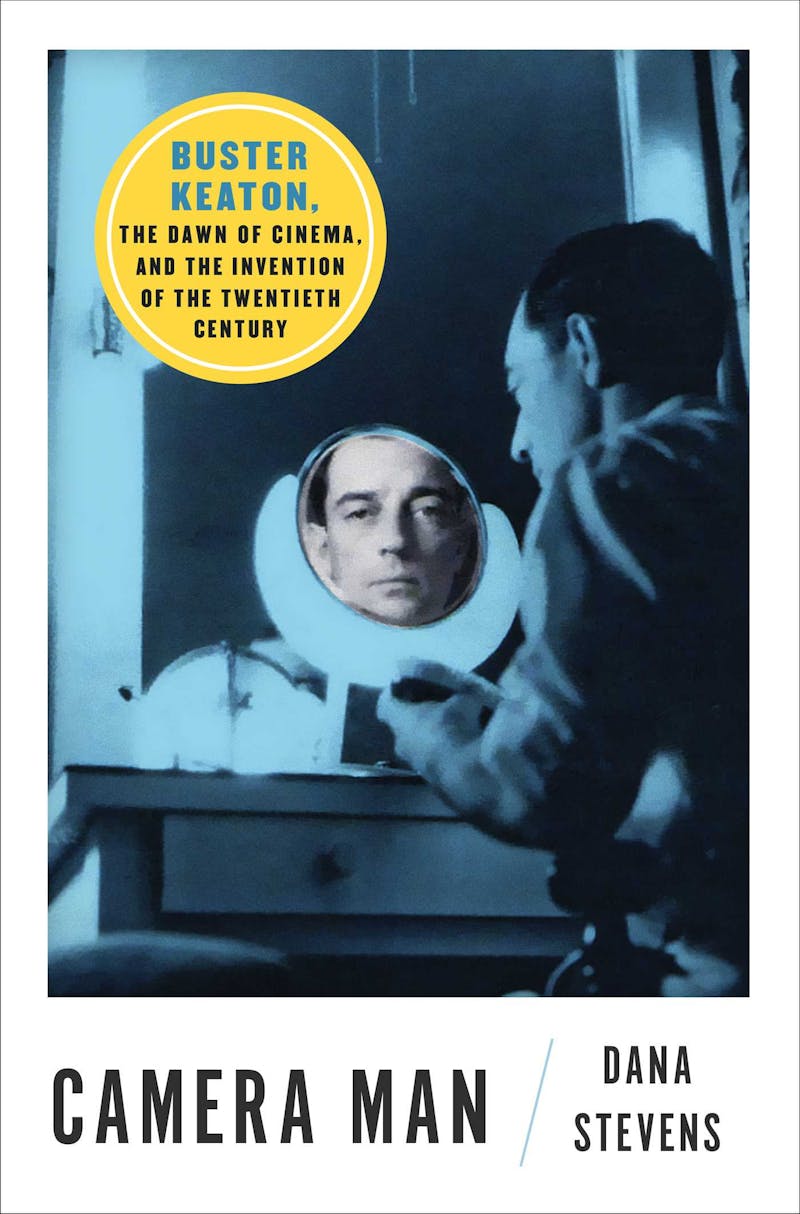

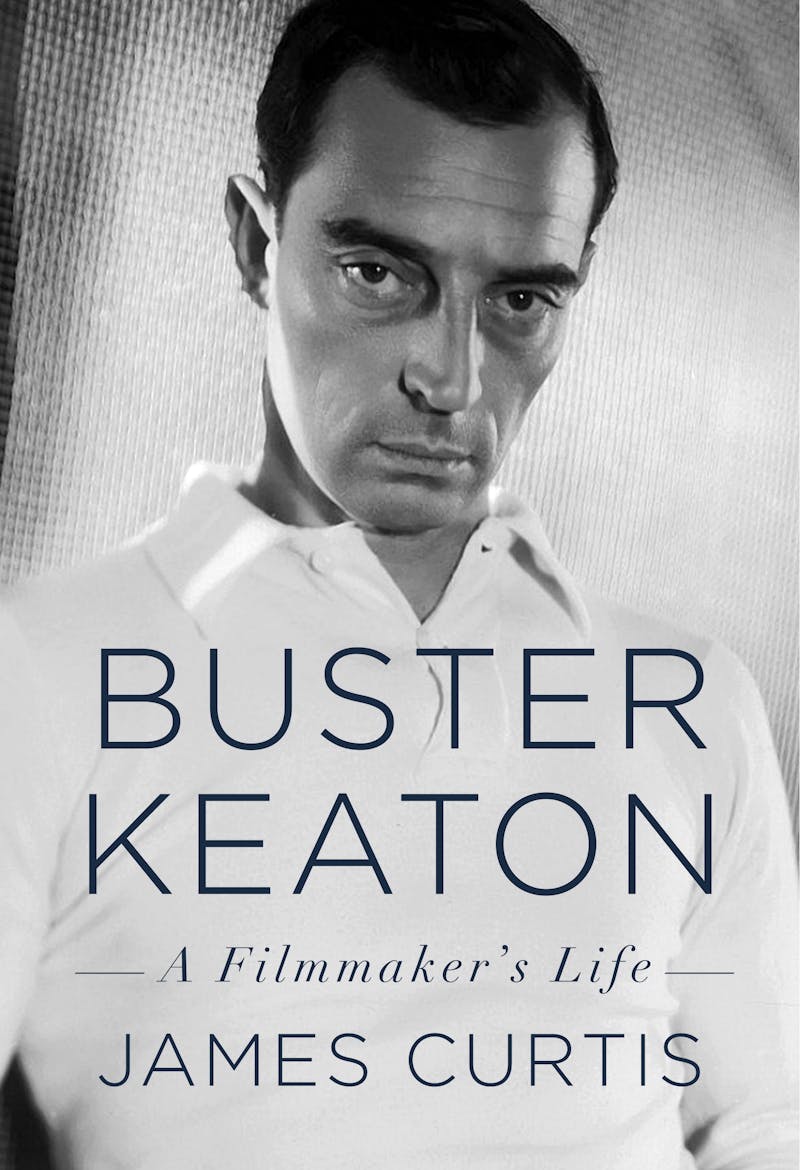

This spring sees the publication of two quite different biographies of Keaton, Dana Stevens’s Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century, and Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, by James Curtis. Stevens is a passionate Keaton fan, and opens her preface by explaining how she fell for him while taking advantage of a steep student discount at the cinema while studying in France. “Who was this solemn, beautiful, perpetually airborne man?” she asked herself. “From what alternate universe, seemingly possessed of its own post-Newtonian laws of physics, had he been flung?”

Stevens is Slate’s longtime film critic, and a popular voice on that site’s “Culture Gabfest” podcast (where, full disclosure, I once interned, and adored her). Hers is a critical biography, less bound to the track of chronology and more nimble, alert to parallels and crossed paths. She goes on long discourses through the life of Keaton’s colleagues and contemporaries, like Roscoe Arbuckle or F. Scott Fitzgerald, but her flair is for close reading.

For example, Stevens explores the architectural symbolism of the dangerous Steamboat Bill, Jr. stunt. Whenever the young Keaton approaches a potential home in his movies, she writes, it transforms into “a space of danger and transformation.” Sometimes the walls spin on invisible axes, as in his many revolving-door gags; always they misbehave. “Structures that seem to offer shelter and physical safety reveal themselves to be nothing but heaps of wood on their way to becoming splinters.”

Only a few years removed from the childhood he spent being flung around the stage by his father, Stevens argues, Keaton was still playing the same vaudeville gag, about “the boy who couldn’t be damaged,” only “projected on a cosmic scale.” For her, the “ephemerality of the built world reveals the foundational homelessness of Buster’s character, whose defining trait is his ability to move through chaos”— violent fathers, weather, physics, the twentieth century—“while remaining miraculously unperturbed.”

Curtis’s book is much less essayistic, and more traditional. A longtime film historian and biographer of Hollywood legends like W.C. Fields and Spencer Tracy, he has produced a book almost 700 pages long and obviously slower, stodgier. If Stevens’s is a work of criticism and context-building, Curtis’s is a narrative history, working interviews and sources into a storyline. There are certain factual parts of the story that Stevens skips over which Curtis clarifies, like the way Keaton actually survived all those extreme stunts as a child. (He claimed never to have broken a bone on stage: “I always avoided taking the impact of a fall on the back of my head, the base of my spine, on my elbows or knees. That’s how bones are broken.”)

Though there are a few discrepancies between the two books—was silent actress Constance Talmadge nicknamed “Dutch” by her mother, Peg, because of her haircut or her “childhood chubbiness,” as Stevens and Curtis have it, respectively?—they mostly make a beautiful pair. Curtis substantially updates the previous “authoritative” life of Keaton, Tom Dardis’s 2002 Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn’t Lie Down, with new source material. Stevens has the flair and comparative approach that as a critic I’d naturally favor; historians might prefer Curtis. Both do excellently in handling the sadder second half of Keaton’s career, after he signed away creative control over his movies to MGM, and gravity, mixed with alcohol, finally began to do its work.

Why Buster Keaton, why now? There’s the centenary of all sorts of events in his career coming up, but the connection to our own era feels deeper. Buster Keaton made entertainment out of nothing, using his body, and the way he combined traditions and invented new ones ended up codifying certain choreographies of movement into something we just today call “comedy.”

For all the business news churn around TikTok and the related turn to short video in social media culture (see: Instagram reels, Facebook Live), there has been little consideration in the critical press of what it all means for motion picture culture more broadly. That’s partly because an influence so ubiquitous is difficult to trace, and the line between social media entertainment and film stardom has become more porous.

In other words, modern entertainment celebrity has become a little more like it was for Keaton, or Arbuckle, or Harold Lloyd, or Charlie Chaplin, people who were their characters. Curiously, like many celebrities of viral comedy content now, Keaton was also professionalized as a child—a much more common phenomenon in the social video era than it has ever been before.

The idea of the raw physical charm of a baby, or a dog, or a clown, is involuntarily compelling to us inhabitants of the twenty-first century. There’s a sense that we still don’t understand why we keep watching this kind of content, but cannot stop. It’s there in the internet-popular, improvisatory comedy of John Wilson or Eric André or Quinta Brunson, performers who carry their act with them. Like Keaton, they might be existentially tortured or deadpan clowns, without a home in entertainment; like a figure in Samuel Beckett, who dressed his lost and confused characters just like Keaton, in battered hats and oversize coats, they stay “miraculously unperturbed” amid chaos.