Not quite the shortest of all Shakespeare’s plays, but the shortest of his tragedies, Macbeth doesn’t run much past two hours, making it tempting for movie directors in search of a little blood and magic. The plot is appealingly clever but simple, and open to all kinds of easy adjustments: Make Lady Macbeth young and lovely, as Roman Polanski did in his 1971 movie, for example, with Francesca Annis, and she seems like a lonely girl hatching an unrealistic plan. Make her a self-assured woman in her sixties, as Joel Coen has done in his new movie, The Tragedy of Macbeth, by casting Frances McDormand, and her scheme is a likelier proposition, and just that extra smidge more evil.

But for all that recommends it for movie adaptation, Macbeth has proven a poisoned chalice for many directors. There’s a tradition among theatrical types of calling Macbeth the Scottish Play or the Bard’s Play, based on the idea that using its name brings down a curse. But Ian McKellen—who played the lead in Trevor Nunn’s almost flawless 1979 production, directed for film by Philip Casson—was right when he wrote that Macbeth is probably considered unlucky less for occult reasons than “because it so rarely works.”

There are three chief difficulties with staging Macbeth, McKellen explains, which all also apply to film. “First: What do you do about Scotland?” The world of the play is explicitly rainy and miserable, and the temptation to rent a castle must be so strong. But straightforward interpretation risks inadvertent comedy, as in Orson Welles’s 1948 Macbeth, with Welles as Macbeth in a stupid hat and with an accent so poor that it was redubbed and rereleased two years later.

The second problem concerns genre. “How can modern skepticism cope with witches, cauldrons, and ghosts?” Without good witches, there’s no good Macbeth. Justin Kurzel’s 2015 very rainy–Scottish Macbeth, for example, led by a ferocious Michael Fassbender, took all the menace out of the witches by making them into realistic local waifs. Then again, if you take the magic element too seriously, as Roman Polanski did, you can end up with animated daggers wobbling, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?–style, through the corridors of Inverness Castle.

The third problem might be the toughest. What should a director do, McKellen asks, about the last act, “in which so many good Macbeths are judged to have failed to thrill?” Instead of a big denouement, as the audience expects, Shakespeare chops the third act into a clutch of anticlimactic scenes of gradual humiliation, as everybody gets a shot at the king.

Coen is the latest in a long line of directors to take a swing. His Tragedy of Macbeth comes to streaming on Apple TV+ from January 14 and was directed by himself alone; he usually works alongside his brother, Ethan. Together they are renowned for unsettling pictures that frequently knit murder with comedy, as Blood Simple (1984) and Fargo (1996) do. The new project was inspired by a production that McDormand acted in at the Berkeley Repertory Theater in 2016. (A frequent collaborator, McDormand has been married to Joel Coen for several decades.) Coen says that there has been no split with Ethan, just that his brother wouldn’t be interested in Shakespeare. Joel is the natural director of the pair, with Ethan credited in their early movies as producer. One can imagine Macbeth’s risks horrifying Ethan and provoking Joel’s interest, for all the same reasons.

To take McKellen’s three problems one by one: Coen transcends the dodgy kilt issue by setting his Macbeth in an abstract place, shooting the film in an almost-square 1.19:1 aspect ratio, in shockingly precise black and white, as if each shot were an etching. With cinematography by longtime Coen collaborator Bruno Delbonnel and design by Stefan Dechant (who, oddly, also did Jurassic Park), the first scene makes the aspect ratio very clear indeed: A plain white field yields to crows, lazily drawing circles in the sky. The clouds become fog, and the crows disappear as a head, then a body, appears, walking away from a battlefield, out of the white.

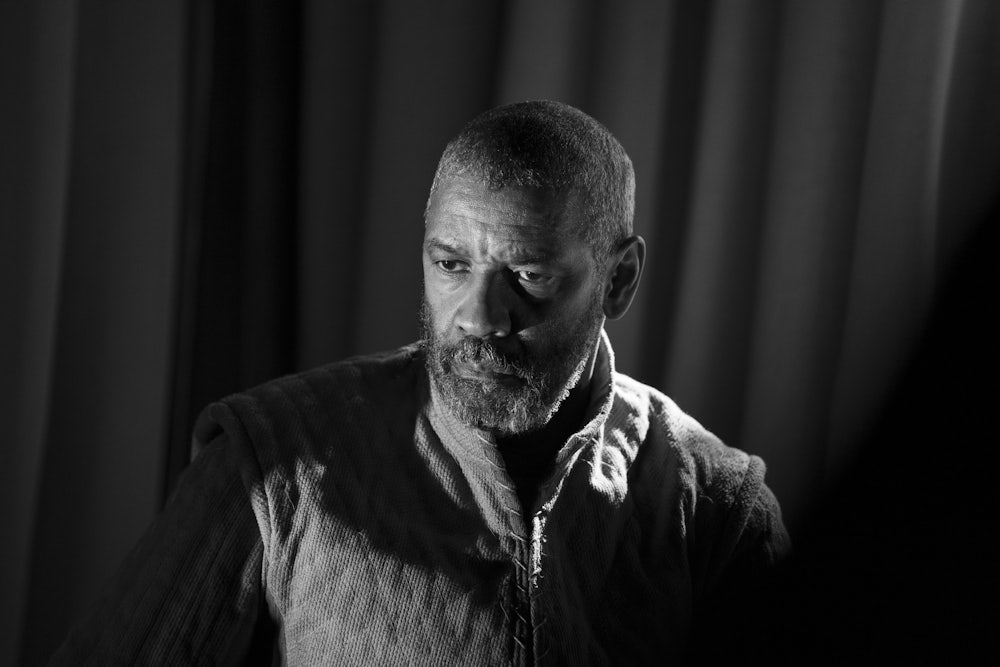

Denzel Washington is from the start a restrained Macbeth, with an expressive voice but an impassive face, except for his eyes, which blaze, but sadly. A muscle in his cheek twitches when he agrees, “’Twas a rough night,” while chatting about the weather, waiting for Macduff to stumble over Duncan’s dead body. Because it’s shot in black and white, and the detailing is so obsessively fine—Banquo has the most extraordinary eyebrows, for example, and you can somehow perceive every detail of their salt-and-pepper hairs—the whole movie has the atmosphere of being very, very tightly controlled, giving new meaning to the words “the charm’s wound up.”

The set is tonally similar to Washington’s acting, being craggy and stark, stylized but minimal. Strongly influenced by the scenic design of Edward Gordon Craig, who exhorted directors to “forget all else and positively look” at the way light works in on their stage, the set is minimal-classical. It looks like a desaturated de Chirico painting or a modern production of Julius Caesar, with exaggerated colonnades picked out in long shadows. Its neoclassicism recalls the 1997 Titus Andronicus movie, in which Alan Cumming’s Saturninus gives fascist speeches in a place like twentieth-century Italy. The square frame contains rectangular scenery; skin texture ripples in high contrast, but nothing is exactly naturalistic.

As far as the problem of magic and disbelief goes, Coen has solved it by casting the legendary Shakespearean actor Kathryn Hunter as all three of the Weird Sisters. She flaps and twists and croaks like a crow, explains the meaning of unknown words with her face, and her sheer presence is explanation enough for the role of magic. She seems to encompass the movie, rather than act within it. It was Hunter who introduced Coen to Craig’s work. In an interview with Vanity Fair, she summarized Craig’s message: “We’ve been spoiling Shakespeare for years by putting him in real rooms, in real castles.… If you get somewhere near what a dream does or music does, then you are getting closer to Shakespeare.”

Because Washington is an actor experienced enough on film that he can change the timbre of his on-screen personality through undetectable alterations in physical and facial expression, problem three—the final act—works. His is a lumbering, sad Macbeth, who spends the movie indoors exhibiting restrained dignity, until finally his shoulders slump, and he gives up. It seems almost a grim joke to him in the end, how completely he’s undone, as Macduff comes at him with the sword.

Macbeth is a dream about power and temptation, a dream that Shakespeare treated from many angles, as in Hamlet, Othello, and every single succession plot in the history plays. We know from Game of Thrones and The Witcher and a hundred other hit stories and video games that dynastic bloodshed in castles sells—Coen could easily have made this a wet, outdoor affair, with snogging and flashing swords and so on. Instead, he has made his star couple into real adults, who seem to drag real responsibilities behind them. In their gravitas, McDormand and Washington are more like the warriors of Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood, which transposed the action of Macbeth to formal sixteenth-century Japan, than the romantic hyperventilators of medievalesque popular television.

Less a portrait of power struggle than a sad dream about greatness in decline, The Tragedy of Macbeth is a gift to fans of slower, starker Shakespeare and a rare exploitation of the benefits to art offered by age.