There was something about the anti-writerliness of Céline that attracted many readers at the end of one horrible world war and well into the next. He never tried to elevate himself over his audience as an authority on anything, especially not art or literature; he never went to university or used academic jargon; and he professed to have read few of his fellow living novelists. A G.P. by profession, he suggested that while literature might be good at diagnosing society’s problems, if you wanted to do real good, you should focus on ameliorating the individual ailments of one patient at a time. “I started in poverty, and that’s how I’m finishing,” he confessed in his 1960 Paris Review interview. For Céline, the only “progress” any individual could hope to make in a solitary lifetime was just getting through it.

From his youth, Céline didn’t feel he belonged anywhere; and he was continually raging against wherever he already was. He was born Louis-Ferdinand Auguste Destouches, in 1894. His petit-bourgeois parents were both overworked and overprotective—his father an insurance clerk who, having given up on his youthful plans of teaching literature, blamed his failures on Jews and Freemasons; his mother was a seamstress who eventually opened her own barely solvent lace shop in central Paris. Forsaken by their dreams, they expected more of the same for Louis and provided him only a rudimentary education, preparing him for a career in the jewelry trade. When he proved rebellious, his father encouraged his enlistment in the French cavalry, and this led to his crippling physical and emotional injuries at the beginning of World War I. He was hospitalized and eventually remanded to a mental facility for a nervous condition that would develop into a lifetime battle with tinnitus. Most of Céline’s subsequent ailments might be diagnosed today as PTSD.

Feeling crushed both physically and psychologically, Louis reinvented his broken self as Louis-Ferdinand Céline—much in the same way that Eric Blair would reinvent himself as George Orwell only a few years later. (Orwell was a lifetime admirer of Céline’s work.) For the next half-century, the person known as Louis-Ferdinand Céline wrote bold, electric, almost psychotically intense novels about the world that had disillusioned him.

After being burned out and wounded in a pointless war, Céline supervised a cocoa plantation in Cameroon and made regular treks into Spanish Guinea, Chad, and the Upper Congo, trading for precious goods and sleeping with “my rifle in my arms for all eventualities.” Then, having trained as a medical doctor, he found work investigating health care in the United States for the Rockefeller Foundation, wrote a report on the Ford Factory’s treatment and mistreatment of employees, and spent time in Manhattan, which he describes in his first novel, Journey to the End of the Night (1932) as a vast machinery of crowds, industrial labor, and commercially designed meals antiseptically displayed in cheap diners where customers were provided “spotless” places to escape their mean lives and all the waitresses resembled “hospital nurses.”

The same author who presented himself as an authority on little more than the messy awfulness of human existence would, however, bring himself misfortune, at the height of his fame, by advocating Hitlerian eugenics in several escalatingly worrisome pamphlets, beginning with Mea Culpa in 1936, which was followed by Trifles for a Massacre in 1937. But most unforgivably, Céline stridently argued for a Franco-German alliance in School for Corpses (1938) with words that would dog him for the rest of his life:

What is the people’s real friend? Fascism. Who has done the most for the worker? The USSR or Hitler? It’s Hitler. You have only to look without all that red shit in your eyes. Who has done the most for the small shopkeeper? It’s not Thorez, it’s Hitler! Who is preventing us from going to war? It’s Hitler! All the communists (Jewish or Jewified) think about, is resending us to our deaths, for us to croak in a crusade. Hitler is good at raising a people, he is on the side of Life, he cares about the life of peoples, and even ours. He’s an Aryan.

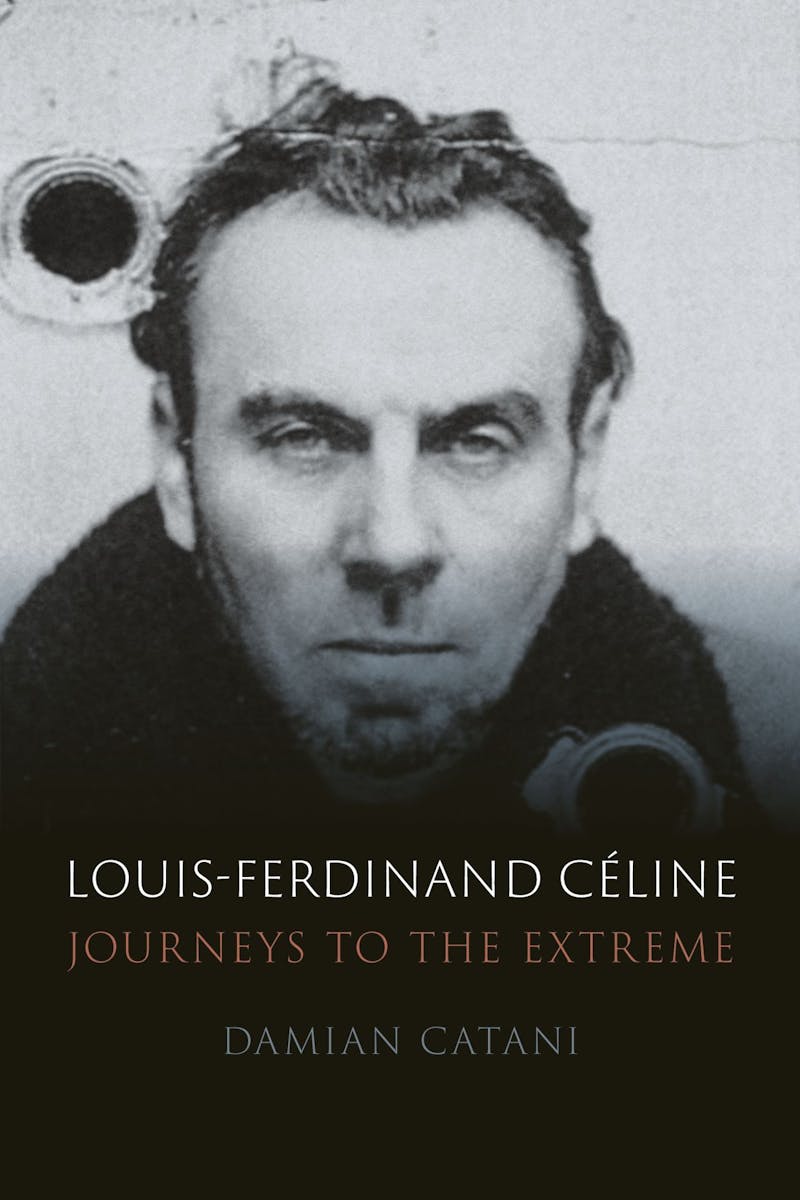

Damian Catani’s new biography, Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Journeys to the Extreme, is the first full-length examination of Céline’s life and work in more than 20 years, and the first to explore the fastest-growing debate of Céline scholarship—whether people should continue reading a Nazi sympathizer. A large chunk of this book considers various opinions, which fall into several obvious camps: those who argue against reading Céline; those who argue he was a nihilist but not a Nazi; those who argue his politics had little to do with the lasting greatness of his books, since the foremost among them—Journey to the End of Night—was published before his fascist polemics started coming along. Since much of the debate has taken place in France, there’s also a strong dose of lit crit terminology flung about concerning how “readerly strategies” should inform our “receptivity” to “texts” and so forth; and while Catani provides a fairly robust critical argument for continuing to read Céline, much of this book has less to do with Céline the writer than with our current anxieties about the responsibilities of literature.

It’s not easy distinguishing Céline’s life from his work: Like Thomas Wolfe, Jack Kerouac, or even Walt Whitman, he spilled his life into fictional forms, made willy-nilly alterations for aesthetic effect, and left readers feeling they were reading the fictionalized life of a man fictionalizing the person he was pretending to be honest about. Confusing? Absolutely. There are at least a couple of long passages in Catani’s book where it’s unclear whether he is recounting Céline’s life or summarizing Céline’s fictional versions of it.

In his autobiographical novels, Céline happily bent and even reinvented the “facts” of his life, presenting himself as an expert on human fallibility and awfulness. He professed that as a doctor, he might do occasional good, but as a man, he wasn’t much good to anybody, especially not to himself. He disdained pride—in one’s self or one’s country—since it fooled men into fighting wars for “Country Number 1” or “Country Number 2” and rewarded them with “a medal and a cough drop for the man who shouts the loudest.” He did not believe that men could bring progress to the world by committing violence against other men, for at the end of every war, as Bardamu (Céline’s fictional alter-ego in his first two novels) explains to a friend:

Nothing really changes. Habits, ideas, opinions, we change them not at all, or if we do, we change them so late that it’s no longer worthwhile. We are born loyal and we die of it. Soldiers for nothing, heroes to all the world, monkeys with a gift of speech, a gift which brings us suffering, we are its minions. We belong to suffering.

Being happy wasn’t what Céline was about. A strong current of misanthropy ran through his work from the beginning, and only the practice of medicine saved him from his worst tendencies. After returning from America, he established a medical practice in Clichy, one of the poorest parts of Paris, and during the first years of this practice, he wrote the heavily autobiographical novel that made him famous, Journey to the End of the Night (1932). Lacking any literary contacts, he hand-delivered the manuscript to publishers until he encountered Robert Denoël, an adventurous editor who took an immediate liking to the revolutionary manuscript and came up with several equally revolutionary ideas about how to sell it.

Denoël invented the figure of the modern literary outlaw as much as Céline, promoting him as an outsider who disdained the airy literary salons of Paris in order to mix freely with the common people as a “doctor to the poor.” Céline’s book shared the common people’s sense of outrage at the everyday horrors of poverty, a pointless war, and a ruling class totally cut off from the suffering it created. And like a French version of Whitman, Céline walked his own road and wrote in the language of common people. In the meantime, he exalted those small pleasures commonly available—sex, good simple meals, and a decent night’s sleep. To dream of greater pleasures (such as a fair society) seemed to Céline almost presumptuous.

Mostly it was Céline’s prose style that energized his admirers: a relentless crackle of observations and condemnations that assaulted the reader’s sense of apartness from words on a page; it upset the literary convention that prose provided fairness, balance, and carefully phrased consideration. Céline raged against his world in almost every sentence; he was robust, untiring, and hilarious in his attacks on everything from fashionable window displays to the wealthy, well-positioned men who directed poorer men to fight wars on their behalf. He careened, he veered, he crashed through everything he saw and heard and felt until it almost felt like his remembered experiences were happening to the reader. To many French people between the wars, it must have felt like sharing the trenches with another soldier who recognized all the pointless madness as they did. Céline made readers feel that, in their angry intelligence, they were not alone.

Céline’s admirers came quickly: Journey was a modest bestseller, receiving prestigious reviews and frequent comparisons to the works of Émile Zola; and Céline gained even more regard due to his failure to win either of the awards many believed he deserved—the Goncourt or the Prix Femina. And while Henry Miller was an early fan (he claimed that after reading Journey, he entirely rewrote Tropic of Cancer), the early English translation was considered inadequate, and it wasn’t until Ralph Mannheim’s version many years later that Céline caught on with disenchanted young American writers coming home from World War II, such as Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut (who wrote admiring introductions to three late Céline novels), and Philip Roth, who called Céline “a very great writer. Even if his anti-Semitism made him an abject, intolerable person.”

Céline’s influence on the Beats (or perhaps their recognition of him as a fellow-traveler) makes perfect sense. Like Kerouac and Burroughs, Céline wrote novels in what seemed like an anti-style—a loosely organized, abrupt, and even somewhat psychotic frenzy of thoughts and jagged observations of the world he saw around him—and mostly despised. The narrative looseness of Journey was one of its charms, swinging from one witnessed atrocity to another—trench warfare, life in a mental hospital (first as a patient, then as a member of staff), the brutalized lives of American workers in New York, and finally the almost helpless state of being a doctor in one of Paris’s poorest neighborhoods. Everything Céline did and saw and wrote bristled with rage at the injustices he witnessed and found himself complicit in. There weren’t many innocent people in Céline’s world, and most of the truly evil forces were always hidden away behind the facade of a stratified society maintained by soldiers, doctors, and bureaucrats like him.

What isn’t quite clear is where Céline’s ugliest opinions about Jews were hiding in his first two novels, which never seemed to pick out any specific region of humanity for special condemnation. His almost conventional rages of antisemitism seemed to come out of nowhere. While he shared meals and friendships with some of Paris’s Nazi occupiers, he carried on friendships with Jews throughout his life, and many prominent Jewish intellectuals came to Céline’s defense after the war. It was almost as if Céline’s political pamphlets were an attempt to map out some of the barely human rage he had inherited from his parents–especially from his father. They confirmed that Céline was never an “intellectual” figure who lived by expressing ideas and philosophies. Rather, he was a poet of emotional human chaos.

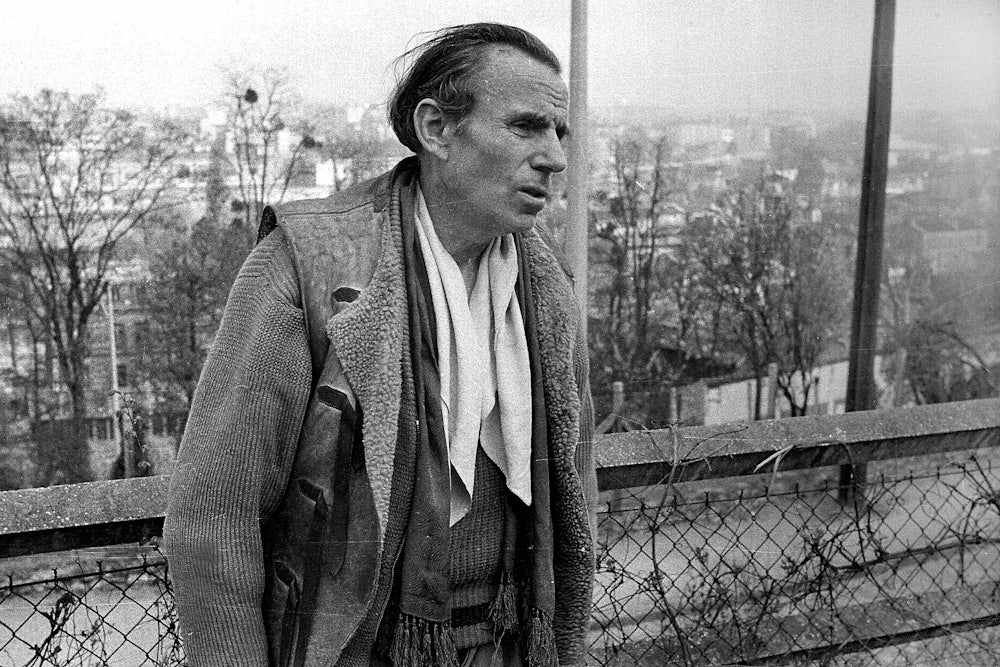

In 1945, Céline was arrested in Copenhagen after a request from France for his extradition for collaboration. While in prison, Céline found his usual solace by writing down his experiences “in fragmentary form”; and during a nine-month period in 1946 he produced 10 pencil-written booklets of thoughts, reminiscences, and experiences now referred to as the Cahiers de prison, from which he mined his final three novels—Castle to Castle (1957), North (1960), and the posthumously published Rigadoon (1969). Those works cover his years fleeing arrest by the Allies, often in the company of Nazi officers and their accomplices, and reflect the chaotic inner life of a man who never stopped running long enough to understand who he was, why he was despised, or where he was going. Céline wrote these last novels in a feverish rush of broken thoughts and sentences (the ellipsis was his preferred punctuation), producing the sensation that these hectic late years were breathless, disorganized, intensely felt, and little more than a series of disordered splashes of experience in a mad rush to the graveyard.

But as Catani’s new book makes clear, the most significant period of Céline’s life occurred after he was dead.

Much of the controversy around Céline crystallized into a series of open literary discussions known as the “Céline affair,” when Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld convinced then–Culture Minister Frédéric Mitterrand to remove Céline from a list of French authors in “national celebration of culture,” in 2011. This action prompted several Jewish authors to object on the grounds that Céline’s political opinions shouldn’t determine the merit of his literary work; and the prominent novelist critic, Philippe Sollers, reminded everyone that there were plenty of other politically questionable authors still being read after the war, such as Jean Genet, who had reportedly slept with Nazi soldiers, and Jean Cocteau, who had freely socialized with Nazis, collaborators, and resistance fighters alike. André Gide defended Céline’s pamphlets for their “aesthetic playfulness,” while one group letter, signed by André Breton among others, claimed that there was not a single line in Céline’s work that “indicates anything other than a purely physical capacity for holding a pen and dipping it in mud.” Only Camus seemed to come down on the fence at the right spot for straddling: He expressed equal disgust for antisemitism and what he called those efforts at “political justice” that sought to punish Céline.

Arguments arose about whether it was more proper to “commemorate” Céline rather than “celebrate” him. Many who argued for Céline’s importance were denounced as “far right,” and those who denounced him as a national traitor were called hypocrites—such as Frédéric Mitterrand, who decided to remove Céline’s name from the “celebration” even while his uncle, François, remained friends with René Bosquet, who reportedly “collaborated in the deportation of Jews.”

Catani argues that French readers stopped trying to decide whether they wanted to read Céline; it became more important to decide whether he was a “good” man. Many similar writers, such as Ezra Pound, had managed to outlive the memories of their most heinous statements; others, like Wyndham Lewis, never recovered; and still others, such as Paul de Man, would only suffer censure after they were dead. But no living artist bore greater witness to debates about the relationship between his fictional and nonfictional writings than Céline.

Catani’s book spends more time wrestling with these political ghosts than it does addressing the specific merits and demerits of Céline’s work. And so Catani defends Céline’s ability to “reappropriate modernity for aesthetic purposes” and for his “recuperative aesthetic strategy”; and claims that his “sentences not only depict the sinister destructiveness of modernity, but they assimilate and devalorize it … and then gradually transform it into an aesthetic spectacle of unprecedented beauty.” The longer the “Céline affair” continued (and in many respects it never ended), the less anybody seemed actually to read his books. Instead, they were working out a linguistic chess game against one another about “valorizing” or “deconstructing” “modernity.”

Céline often claimed that he wasn’t writing novels so much as communicating raw emotions to his readers. As he told a friend: “What interests me is a direct message to the nervous system … I can’t stand idle chattering.” But of course “idle chattering” is a big part of what most conversations are all about: Hi. How are you. Where you been? What’s that on your shirt? Have you seen Betty? And whatever readers decide about Céline’s worthiness or his politics, he no longer reads as well as he once did. Nor does he provide very good company.

Today, even the best of Céline’s books feel too long, meandering and repetitive. No matter how readers approach him politically, it is hard to see that he remains as challenging, provocative, or even as profane as he once did. And while the books deliver long passages of raucous good fun and occasionally surprising and beautiful prose, they don’t measure up to the work of many of his admirers, such as Henry Miller, Vonnegut, or Roth. And when considered alongside other modernists—such as John Dos Passos, James T. Farrell, or even Zola—he seems an inferior and less inventive novelist.

It is often interesting, or even exhilarating, to witness genuine human emotions pouring forth from raw, unusual books like Céline’s; but after a few hundred pages or so, all that emotional intensity seems like too much of a good thing. Like the surprisingly articulate drunk person who sits down next to you in a bar and starts emoting about his recent rages and anxieties, it grows tiresome when those expressions lose focus or detach themselves from any coherent narrative. When that person never leaves and never stops talking, he might even start to sound a little like Louis-Ferdinand Céline.