Well, 2021 is ending with a decided whimper in Bidenland—no Build Back Better, as timid or bullheaded Senate Democrats continue to insist that the filibuster fosters unity. It’s a long way from how the year started out.

It also means that the prospects of legislative accomplishment in 2022 are something less than bright. Maybe some form of Build Back Better will still pass, after Joe Manchin killed the current version, but it will be a fraction of what once seemed possible. Manchin has only emerged from this process stronger than he was before. The system, from the elite media to the folks back home, who gave him a 61 percent approval rating in November, has reinforced the idea that obstinacy equals leverage—giving him nearly single-handed power over the legislative process in 2022.

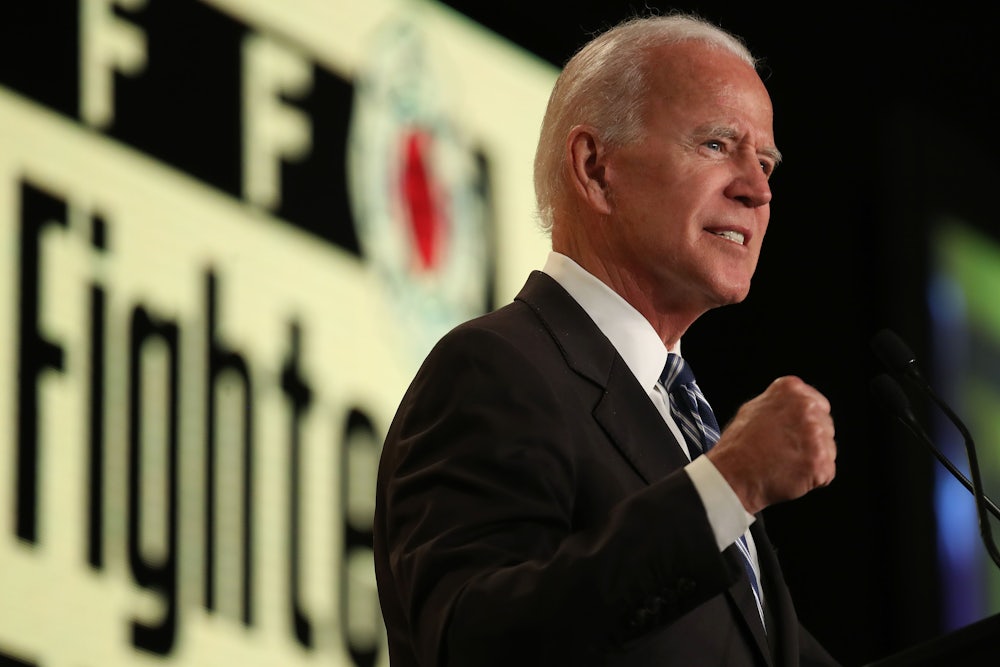

What is Biden to do? Most people think that when a legislative agenda stalls, the presidency itself is dead. But that isn’t true here. There’s a set of issues that Biden can at least begin to address largely without Congress, and they are vitally important issues whose reform can make more—possibly far more—difference in people’s day-to-day lives than anything Congress could do: The Biden administration needs to turn aggressively to taking on monopolies and oligopolies.

Most Americans are unaware of it, but monopolies and oligopolies run their lives to a staggering extent, determining their consumer choices and how much they pay. And it’s not just consumers—it’s small-business people who have to deal with monopoly or oligopoly corporations (Google “Tyson Perdue Cargill chicken farmers”). It’s not for nothing that one of the eight items in FDR’s “Economic Bill of Rights” of 1944 was “the right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad.”

Biden is serious about this stuff. Last July, he issued an impressive executive order on competition and monopoly power. In a speech accompanying its release, he said: “The heart of American capitalism is a simple idea: open and fair competition. That means that if … companies want to win your business, they have to go out and they have to up their game; better prices and services; new ideas and products. But what we’ve seen over the past few decades is less competition and more concentration that holds our economy back. We see it in big agriculture, in big tech, in big pharma. The list goes on. Rather than competing for consumers, they are consuming their competitors.”

It’s the right framework. “It was a reenvisioning of how we use the state,” Barry Lynn of the anti-monopoly Open Markets Institute told me. So what can it mean, specifically?

The short answer is: just about everything. At this point, 40-plus years after Robert Bork (yes, that guy) turned U.S. monopoly law and policy on its head, monopoly has seeped into so many aspects of our commercial lives. Everyone points to Big Tech, and sure, it’s pretty evil. But one thing about Big Tech is that, for the most part, it’s free. We don’t pay Facebook anything (except our data and our privacy). But other monopolies and oligopolies make us pay through the nose, or they limit our choices, or they squeeze out small competitors. Prescription drugs. Hearing aids. Hospital beds. Airline tickets. Eyeglasses. Beer. Candy. Cheerleading uniforms!

Americans don’t like this. They’re not that wise to it, but to the extent that they are, they smell a rat in a big way. A CNN poll from early November was brutal. When asked whether they thought Facebook made American society better or worse, just 11 percent of respondents said better and 76 percent said worse (no wonder the company changed its name to Meta). And when asked if government should regulate Facebook more, less, or no change, only 11 percent said less, while 35 percent said no change—and 53 percent said more.

Biden has the right team in place. Jonathan Kanter at the Justice Department’s antitrust division has a reputation as a real crusader; ditto Lina Khan at the Federal Trade Commission. Another appointee, Tim Wu, who joined the National Economic Council, coined the term net neutrality. It’s about as encouraging as a team could be.

Not a lot has happened yet. Kanter was just confirmed in November. At the FTC, Khan has taken some steps, for example warning business owners about using fake customer reviews. This sounds pretty mild to you and me, but to a corporate America that’s had most things go its way for four decades, it’s a declaration of war, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has responded by FOIA’ing some of Khan’s communications with colleagues.

That shows what a fight this will be, if Biden decides to truly engage it. The administration has to pick the right targets—not just Big Tech, which everyone knows about, but the things that people have no idea about. Something that hits people emotionally. Conservatives are so much better at this kind of symbolic stuff, the way they find the one sympathetic needle in a haystack of shysters and grifters around which to build their P.R. case. Biden and Democrats need to make the cost of monopoly power real to people.

The economist Thomas Philippon estimates that monopolies cost the typical family $5,000 a year. That’s more than most people would get from a Democratic child tax credit expansion or a Republican tax cut. That’s how big this is. Biden and team should pounce on that figure and break it down for people in a massive public education campaign. If they do that well, public opinion will be firmly on their side and will support whatever actions the administration takes. Being known as the champion of consumers and small-business people against giant monopolies could do wonders for Biden’s image. And who knows? I’m not aware of many huge monopolies based in West Virginia, so if Biden ever needs Congress’s votes on an anti-monopoly measure, he might even get Manchin’s.