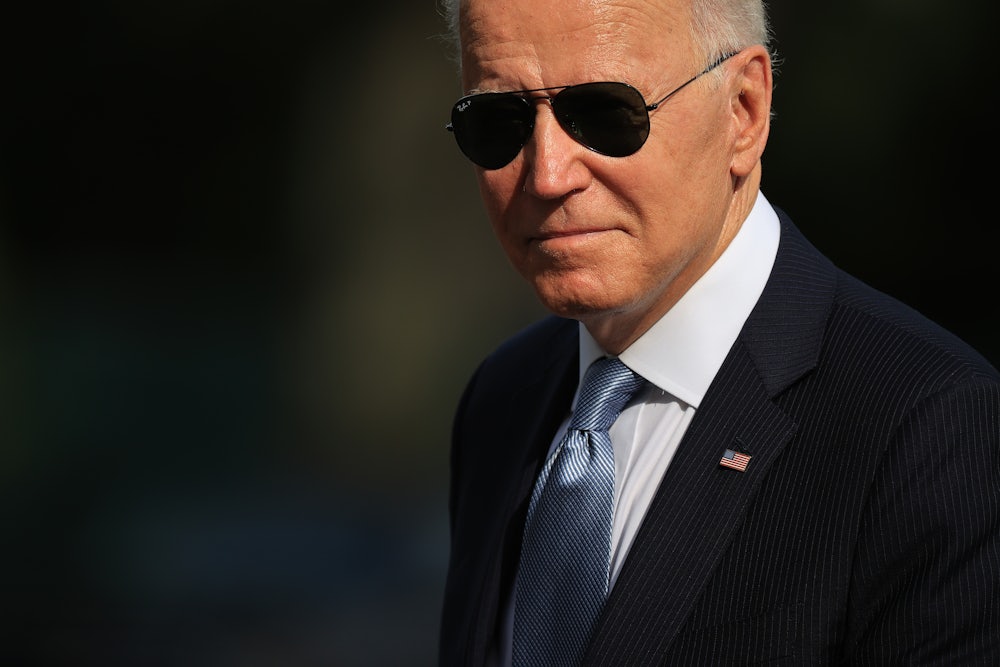

After six months of indecision, President Joe Biden announced on Tuesday—finally—a nominee for one of the most crucial positions in his administration. Jonathan Kanter, a plaintiff’s lawyer critical of the tech industry, will run the Department of Justice’s antitrust division. In that perch, he’ll be expected to lead the DOJ’s ongoing antitrust case against Google and to possibly pursue other cases and enforcement actions that could lead to the breakup of some of the massive tech companies denounced by Democrats and Republicans alike. Kanter, who held positions at the Federal Trade Commission and the corporate law firm Paul Weiss LLP before setting out with his own boutique antitrust practice, has sued Google—on behalf of Microsoft—and was widely seen as the favorite pick of anti-monopoly advocates, who see an opening to restore competition to the American economy far beyond just the technology industry.

In appointing a confirmed opponent of big tech to one of the most influential and important enforcement positions in the administration, Biden is firmly aligning himself with progressive consensus. Whereas the administration has seemingly been treading water on issues ranging from national security to immigration, Biden has avoided the temptations of industry inducements and regulatory capture by staking out a bold position that will undoubtedly send tech lobbying expenditures through the roof. The road to breaking up even a single overconsolidated tech giant is long—not to mention the path to reforming whole sectors of the economy—but Biden has given would-be reformers their best hope for success in a long time. With similarly minded appointments across his administration, Biden has found his trustbusters, a team who are likely to challenge the terms of our economic dystopia head-on.

To be clear, Kanter is no woolly academic or frontline activist. He spent years as a sort of resident tech gadfly ensconced in big law firms, and he’s represented companies like Yelp, News Corp, and Spotify. (In today’s attenuated tech landscape, these billion-dollar companies may count as underdogs compared to their overwhelming rivals.) But unlike other floated appointees, such as Renata Hesse, Kanter is not seen as friendly to industry. Google may very well follow the example set by Amazon and Facebook, which asked for newly installed FTC Chair Lina Khan to recuse herself. But they’re unlikely to put a dent in his or the DOJ’s agenda, which is firmly centered on reviving the activist antitrust tradition. Kanter’s feelings were made clear during a panel in 2018: “Monopoly cases are the equivalent of jaywalking,” he said. “You just don’t see them.... The last big Section 2 case brought by the United States government, under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, is the Microsoft case 20 years ago. So what has gone wrong? How have we lost our way?”

The announcement of Kanter’s appointment was immediately hailed by a who’s who of the left-liberal establishment, including Senator Amy Klobuchar and Senator Elizabeth Warren. “Jonathan Kanter’s nomination to lead @TheJusticeDept’s Antitrust Division is tremendous news for workers and consumers,” tweeted Warren. “He’s been a leader in the fight to check consolidated corporate power and strengthen competition in our markets.”

Advocacy organizations focused on economic competition and fairness published a flurry of supportive statements. “The public needs an Assistant Attorney General with both strong legal know-how and the requisite boldness to challenge gatekeepers and consolidated markets, including broadband providers and digital platforms,” said Public Knowledge, a nonprofit that works on internet and copyright issues. “Jonathan Kanter fits that bill.”

Others have gone even further in calling Kanter’s appointment a fulfillment of Biden’s pledge to remake the economic landscape in a spirit of fairness and democratic participation. “In naming Jonathan Kanter to run the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, the Biden administration proved that they are truly serious about fully restoring American democracy,” said Barry Lynn, executive director of the Open Markets Institute, in a statement. “As Open Markets has long made clear, today’s monopolists pose the greatest domestic political threat to Americans since the Civil War. Jonathan Kanter is the right person for this moment—someone who knows how to break the fist of private power and build a rule of law for the digital age.”

Along with FTC chair Lina Khan and Tim Wu, who sits on the National Economic Council, Biden’s team has assembled a troika of leading thinkers on antitrust and economic competition, who together are known as part of the New Brandeis antitrust movement. Born in the last decade out of concerns regarding overconsolidation across the American economy—and a sense that existing antitrust policy had proven insufficient to the challenge—“the movement believes that excessive concentration is not just an economic threat, but a threat to democratic values,” according to one manifesto. “Subjecting private power to antitrust scrutiny and ensuring ‘fair competition’ is both an economic and political imperative.”

It’s that awareness of private power, and the imperative to challenge it, that seems to excite supporters of Kanter, Khan, and Wu. It’s not just that companies like Google and Facebook are so big and powerful (though neither matches the $2.1 trillion market capitalization of Microsoft, which survived its own late-twentieth-century brush with antitrust scrutiny and deserves to come in for another drubbing). It’s that these enormous conglomerates represent an entire way of economic organization—an unjust one—in which private monopoly is allowed to exercise tremendous influence over how people live, work, and consume without being subject to democratic or legal accountability.

The New Brandeisians would argue that monopoly itself is the problem, as it was during the first Gilded Age. It compromises democratic decision-making, undermines labor power, erodes competition, rigs markets, and funnels outsize profits to a small ownership and executive class. That’s why Biden’s recent executive order on economic competition, which mandates an array of initiatives across government to promote everything from net neutrality to the elimination of noncompete agreements, has also activated supporters (as have a handful of antitrust bills introduced in the House). In moving from that executive order to Kanter’s appointment, Biden has shown a surprising willingness to push ahead on policies that could have enormous economic impact and do as much to burnish America’s wounded democratic image as preserving voting rights would.

As of now, this idealized future of tamed corporate power is a notional one. But we are witnessing the emergence of a broad and coherent plan finally to put teeth to regulatory and antitrust policy. And unlike other Democratic initiatives, challenges to big tech tend to pick up a few sympathetic votes from congressional Republicans, so while Kanter’s appointment is far from a fait accompli, it seems likely to move forward. That is not to forecast some coming era of bipartisan comity on how to challenge tech monopolies: Petty squabbles and Republican obstruction are likely to remain enduring features of the landscape. But if Democrats were savvy, they’d recognize that they have the makings of a real populist movement here, one founded on ordinary people’s material interests, not empty culture-war issues. If executed and sold properly, it’s a potential rarity in politics: a winning policy, and a just one.