Joe Biden has the opportunity to be America’s first trust-busting president in at least 50 years. He could go down in history as the smiling man on the back of an Amtrak train, declaring war, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt did nearly a century ago, on the “privileged princes of these new economic dynasties, thirsting for power” and the “economic royalists” who had seized control of the lead institutions of the American political system to consolidate their grip on economic power. Biden could be a hero to corn farmers and laundromat owners who were almost crushed by Covid and Wall Street, a tribune for warehouse workers, truck drivers, and taxi drivers who almost lost all their organizing power—the man from Scranton who fought for the people against the powerful.

What’s more, he can do all this without much reliance on the slender Democratic majority in the House of Representatives—or an evenly split, at best, U.S. Senate. Using the long-dormant and atrophied regulatory powers of the executive branch, Biden can change the game for small businesses and workers, smashing up some modern trusts, while forcing others to divest themselves of vertically integrated market power under threat of more far-reaching regulatory breakups.

The basic approach here is entirely in line with Biden’s already announced first 100 days agenda, which lays out ambitious new enforcement initiatives across the federal bureaucracy. With the right appointments, Biden’s team can use the considerable powers at the Federal Trade Commission, the Treasury Department, and the Department of Justice to create a more level playing field for the dangerously top-heavy American economy—made all the more unequal by the Covid-19 crisis. And he can home in on the rigid monopolies that have overtaken key sectors of the economy by instituting ambitious models of fairness and equity within the Department of Agriculture, the Federal Communications Commission, the Department of Energy, Health and Human Services, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Education.

The basic methods at his disposal are the same time-tested means by which federal bodies have long targeted the unjust consolidation of monopoly power: enforcing existing laws, and bringing far-reaching new antitrust actions, while using the rulemaking authority of individual agencies to safeguard the interests of workers and smaller players in the sprawling U.S. economy. A trust-busting Biden White House can face down the anti-democratic excesses of big capital, stop the most extreme abuses of monopolistic power, and bring big ag, big tech, and big pharma and health care and hospital networks back down to recognizably human scale—and back within the sphere of basic civic accountability.

There may be, indeed, no other path forward, as Biden’s incoming Cabinet reckons with the many daunting challenges of engineering a new approach to Covid relief. If Mitch McConnell is again using a GOP Senate majority to thwart any direct stimulus packages, Biden will have to find ways to make big companies redistribute wealth via market mechanisms, as opposed to having checks sent directly to citizens, which propelled last year’s Covid recovery stimulus.

There is ample precedent for such an approach. The last time we were in a depression of this scale, Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried to stimulate the economy from the top down, with the command authority briefly granted to him under the National Recovery Administration, and failed. During the latter phase of his administration—the more successful one—Roosevelt came to understand that a thriving society could only be reconstructed via a head-on battle with big financial interests. That crusade worked to stimulate the economy by breaking the chokehold of well-funded monopoly men.

Just as important, given the precarious political footing of the incoming Biden administration, is the potent electoral appeal of such an agenda—something that FDR also well understood as he instituted federal income supports as the basis for a Democratic governing coalition that spanned generations. Antitrust is one of the few policy arenas in which aggressive action will win Biden the devoted support from the activist left wing of the Democratic Party, while splitting apart and exposing the always unsustainable economic arguments mounted against crony capitalism by self-styled populists on the right. For starters, this realignment of the Democratic Party’s vision of the American political economy would go a long way to help Democrats win the Senate in 2022—a cycle that boasts an unusual number of vulnerable GOP incumbents, weighed down with the dismal Trump-McConnell legacy on Covid relief.

The opportunity that Biden and the Democrats need to seize here stems from the basic fact that antitrust politics is not like other politics. Traditional left and right loyalties simply do not hold within its orbit. The economic populists of the right hate corporate monopolies as much as working-class progressives and immigrant small-business owners do. It’s not for nothing that Ted Cruz keeps yelling about monopolies—or that Trump, when he first campaigned in 2016, and when he was clearly losing in 2020, turned to attacking corporate monopolies. Trump of course reneged on his trust-busting promises, but he understood the rhetorical power of saying that “big media, big money, and big tech” were all against him. On the front lines of Democratic policymaking, meanwhile, a generation’s worth of neoliberal giveaways to these sectors is finally yielding to a new social democratic consensus. In antitrust politics, Amy Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders share their anger with Andrew Yang and Scott Galloway—a beloved tech business guru who rooted for Bloomberg.

Within the electorate proper, the depth of the emerging new antitrust consensus is even more striking. One recent poll by Data for Progress showed that 74 percent of Republicans and 80 percent of Democrats are “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about monopolies in the U.S. economy. The same survey showed the number of people who support breaking up big tech companies outnumbers those who oppose it by a two-to-one margin, again with no significant Democratic-Republican divide on the question. Indeed, some surveys now show that Republicans are more likely to see tech companies as having too much political power. A Harvard CAPS/Harris survey found similar numbers in 2019, with nearly 70 percent of voters saying that big tech should be subject to antitrust review, and had used market power to gain enormous profits. Almost two-thirds of Americans also told Data for Progress they wanted actions against big tech.

And while big tech soaks up a great deal of attention as the most recent monopoly player on the block, the same trend holds through most major sectors of the U.S. economy—voters see a plague of bigness, and are increasingly clamoring for the federal government to intervene. A 2020 poll by RuralOrganizing.org found that among rural voters, fighting corporate power is a top priority. Sixty-nine percent of the respondents in the survey believed that “a handful of corporate monopolies now run our entire economy.” Almost half said they’d be more likely to support a political leader combating this pattern of top-down concentration and endorsed “a moratorium on factory farms and corporate food and agriculture monopolies.” Opposition to the 2018 Bayer-Monsanto merger reached as high as 93 percent in one poll, with critics citing very sophisticated economic arguments for their opposition. More than 90 percent of respondents, for example, were concerned that the newly merged ag-and-medical giant would “use its dominance in one product to push sales of other products.”

These aren’t the voices of diehard Democrats with a few Republican crossovers, or vice versa. Within traditional political and policy disputes, you don’t see anything close to such openings for trans-partisan accord. In one representative 2020 Hill-HarrisX survey, for instance, 88 percent of Democrats supported Medicare for All, while 46 percent of Republicans did. Antitrust, by contrast, is foundationally bipartisan, interdenominational, cross-cutting—everything Biden said he wanted to be during his general election campaign and in his victory speech. Unlike other well-flogged economic or culture-war issues, antitrust affords an inviting path out of the bitter cul-de-sacs of prevailing political debate. In an age of trench-warfare–style base mobilizations, the antitrust agenda promises something else: a vision of widening opportunities for ordinary citizens, the basic American civic ethos of giving people a fair shot, and a governing plan that could actually unite Republican and Democratic support.

Why is it so different? People’s anger at corporate concentration comes more from their own experience than from political leaders, and the most partisan media outlets don’t cover it much, or in any appreciable level of policy detail. You don’t find much discussion of monopolization on either MSNBC or Fox, let alone CNN or NPR. People on their own have decided that we have a very deep problem of corporate concentration, and they want elected officials to fix it.

When I spoke to chicken farmers, taxi drivers, and Spectrum electricians for my book on corporate monopolization, they weren’t parroting talking points, but speaking from experience of abuse and humiliation. People know the basic truth of monopoly power in our time, even if three generations of economists have missed it: The more power big companies have, the worse life is for workers and small-business owners. Because the news coverage has been so limited, however, they don’t always know that their struggles are exactly what many other economically disenfranchised Americans are going through. Instead, they’re apt to see the scourge of economic privilege as bad actions of a particular tyrant, like Tyson, or Uber. But when I shared a draft chapter on taxi drivers with one chicken farmer, he told me he wept. “I had no idea they were dealing with the same thing,” he said. “This is un-American.”

What explains the unusual alignment is precisely the key feature of antitrust that I have found the hardest to communicate to elites who, in one way or another, seek to banish the antitrust issue to the sidelines of mainstream debate. Yes, sure, the refrain goes in such circles: but later, first the real stuff. The problem here is, as with all problems of economic concentration, the failure of political imagination. It’s true that monopoly isn’t a discrete “issue.” Monopoly isn’t a problem, the way that, say, tax evasion is a problem. Nor is it an issue the way that our total failure as a society to provide health care to sick people—and preventative care to all—is an issue.

Rather, monopoly is all of those problems—and more. It is constitutional, not epiphenomenal. It is the operating system of our economy, a Trump-level problem, an assault on the whole project of self-government. The four largest beef firms collectively control 85 percent of the market share in their sector—and the similarly top-heavy corn seed, soybean, and herbicide markets aren’t merely the popular winners in an evenly weighted contest for consumer allegiance. No, these companies control the men and women who depend on them. Farmers and farmworkers are abused serfs in the Tyson-Monsanto oligarchy, and they don’t like it. Farmers who are going bankrupt at the highest levels since the Great Recession and farmworkers who have been forced to wear diapers because they don’t have break times to pee aren’t living amid some outlying set of pathological conditions at the margins of otherwise fundamentally decent market competition and humane workplace regimes. Rather, they’re suffering at the hands of a pathological government that is designed to extract as much value as possible and leave the farmer only enough to survive—if that.

When Google and Facebook dominate digital advertising and social media, it isn’t an “issue,” it’s a democratic crisis. Handing over de facto top-down management of the public sphere to Facebook and YouTube, with their hundreds of millions of American users, is frankly nuts. Who would choose Mark Zuckerberg as king of the truth? What kind of healthy democratic communications realm is run by a handful of people—let alone a group whose job is to maximize engagement by maximizing conflict among users and fomenting paranoid conspiracy theories for profit? What could be more important than going at the root cause of why workers’ wages are stuck in the mud while CEO wages soar, and tech monopolies such as Uber are consolidating their power to exploit workers and punish labor organizers?

It looks as if America might finally be on the verge of doing something about this problem. Last December, 46 state attorneys general, led by Letitia James in New York, filed a lawsuit designed to break up Facebook for illegally buying and burying competitors. And on October 6, 2020, the House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law put out an astonishing product: a scorching, 450-page report that detailed in unstinting and precise prose exactly how the four largest tech giants—Apple, Facebook, Google, and Amazon—had built their extraordinary profits not just on ingenuity, but also on anti-competitive behavior. In the report’s foreword (composed jointly with New York Democratic Representative Jerrold Nadler), the subcommittee’s chair, Rhode Island Democratic Representative David Cicilline, did not mince words: “To put it simply, companies that once were scrappy, underdog startups that challenged the status quo have become the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons.” The Cicilline report did not just list a few problems together with a fistful of half-measures to create the appearance of official concern; it represented a profound split with 40 years of thinking on democracy and economics.

Since Ronald Reagan began overthrowing FDR’s New Deal consensus in earnest in the early 1980s, the official doctrine of the country has been that big companies are only problematic when there is overwhelming reason to think that they charge higher prices, or do something blatantly akin to price-gouging. The Reagan doctrine of corporate rule was that big is good, efficient—and that investors’ interests are radically aligned with the interests of the rest of society. It therefore stood to reason that self-interested investors would only pursue strategic choices that led to innovation for consumers—which led in turn to lower prices, and greater social well-being.

The Reagan doctrine of the American person was as crabbed and confining as his corporate vision was expansive and broad. Under this new corporate dispensation, Americans were understood solely as consumers, not citizens (let alone workers, small-business owners, or community members). And this premise led to the same basic conclusion that the new vision of corporations as Promethean engines of the greater social good did: Industrial policy should be a pure reflection of this suffocatingly narrow understanding of consumer welfare. The high priests of the doctrine were law-and-economics jurists such as Robert Bork and Richard Posner, who had both built on the work of Aaron Director at the University of Chicago Law School. Director and his neoliberal colleagues, such as economists Milton Friedman, James Buchanan, and Frank Knight, had long insisted that economic disputes were best left to the recondite deliberations of the market’s own practiced masters—and that the whole notion of any sort of public interest was a self-interested myth of scheming federal bureaucrats.

While there have been minor disagreements about the scope and meaning of consumer welfare as the ultimate standard of enlightened policymaking, this upside-down theology of neoliberal governance has been so complete for 40 years that the disagreements largely operate within the doctrine, not outside it. It is a powerful and self-reinforcing article of faith, because success in the marketplace becomes prima facie evidence of excellence in serving the consumer welfare standard; if people are buying it, it must be good for people, and since people are consumers, we need only look at whether they are buying it.

Cicilline’s report took this fraying ideology of market idolatry and turned it on its head, by delving deeply into the far-from-consumer–empowering business practices of the big tech companies. The report concluded that these companies were not successful by virtue of the service they provide to consumers, but rather because they were effective in bullying rivals, shutting out competition, and forcing their products on all of us as the only remaining options. Each of the big four companies had ceased to be operating within a market as classical economics understands it. Instead, they had come to control their respective markets. They mounted this crackdown via top-down measures to commandeer market share and cartelize labor markets, together with proprietary models of user-surveillance and targeted advertising, across social media, e-commerce, and apps, and vast swaths of the consumer economy. The big four used and grossly expanded their power, the report found, by “charging exorbitant fees, imposing oppressive contract terms, and extracting valuable data from the people and businesses that rely on them.”

The recommendations of the report include breaking up big tech companies, forsaking 40 years of bad Supreme Court case law, and making it easier to bring consumer and class-action lawsuits against unfair business practices. It proposed prohibiting these platforms from preferring their own products, eliminating forced arbitration in disputes with consumers, and making the enforcement agencies charged with regulating the big four more transparent.

Cicilline’s report also took the tech monopolies to task for their intransigence in fulfilling requests for documents from the subcommittee that would help shed light on business practices. It also called out federal regulators themselves for their own anemic performance in the tech sector, arguing that “the antitrust agencies failed, at key occasions, to stop monopolists from rolling up their competitors and failed to protect the American people from abuses of monopoly power. Forceful agency action is critical.”

On this latter score, Cicilline’s committee led by example. The subcommittee’s staff forced the companies to hand over a million documents and communications, without actually using a subpoena—probably because the companies knew that the committee wouldn’t shy away from issuing them. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos let it be known he’d rather not testify before the committee on his company’s competition-killing practices and well-documented labor abuses. But he came anyway, because Cicilline said no one was above the law and was prepared to ensure that his legal staff followed through.

And when Bezos finally appeared, he made a confession worth the entire project alone: He admitted Amazon’s algorithm that determines which seller is featured is based on whether a seller uses Amazon’s shipping and warehousing service, Fulfillment by Amazon. You don’t have to be an antitrust lawyer to see how that stinks of brute coercion (I’ll treat you well if you just use our service). And if you are an antitrust lawyer, you’ll recognize it as illegal tying—the very sort of market-rigging behavior that antitrust agencies are supposed to stop.

Even with such dramatic findings, it was all too easy to imagine Cicilline’s report getting swept aside amid a resounding (and lavishly tech-funded) Biden landslide. But we aren’t in October anymore. When the report came out, Joe Biden was polling up to 12 points ahead of Donald Trump, and had been winning in virtually every poll for more than a year. In the immortal words of CNN, there was “no indication that Trump’s four-year–long campaign for reelection has managed to garner him substantial new supporters.” The website FiveThirtyEight declared that Democrats would recapture a Senate majority in 67 out of 100 scenarios, and people were busy sending money to Theresa Greenfield, Amy McGrath, and Jaime Harrison—former long-shot Democratic Senate prospects who now seemed as though they could ride a Biden-led blue wave into a bold new Democratic Senate majority.

But the close results of the 2020 election make it all the more important that Biden embrace the substantive findings of the subcommittee report, because antitrust politics is good politics. It’s true that the Republicans on Cicilline’s subcommittee didn’t endorse all the report’s recommendations (like structural separation of business operations within big tech). But a concurring report issued by Colorado Republican Ken Buck signed on to the report’s key finding that big tech monopolies are abusive and bad for the economy, together with its underlying institutional argument—that Congress should reassert its power and stop letting the executive branch agencies quietly fail. This broad cross-partisan accord strongly suggests that Biden should throw his full weight behind the report, and force individual senators who are presently blocking its legislative recommendations to explain to their constituents why, exactly, they are siding with Google.

One important reason Biden could afford to take on this fight is that it wouldn’t require him to place any faith in Mitch McConnell’s roundly disproved record as an honest broker of bipartisan agreement. That’s because anti-monopoly politics is unusual in another way: It has sanctioned presidential industrial-policymaking power at its apex. Biden has a responsibility to fully exercise the powers granted to the presidency in a long-standing battery of antitrust legislation by the Congress of 1890, the Congress of 1914, the Congress of 1921, and the Congress of 1934. These measures, all aimed at curtailing the unchecked excesses of monopoly power in the American economy, grant presidential agencies a legislative brief: the responsibility to write, rewrite, and update the rules governing who can make what kind of contracts with whom, and what constitutes unfair behavior, and who can merge under what conditions. The latent power of these tools is extraordinary, by design.

Again, consider the legacy of Reagan. He flipped the script on antitrust immediately upon coming into office. He was very close to Edwin Meese—later his attorney general—whose priorities were ending affirmative action, scaling back the rights of prisoners and those accused of crimes, and freeing corporate power from the shackles of governmental oversight. Meese duly recruited Bill Baxter as the antitrust head of the Justice Department—who in turn issued new guidelines proclaiming that “mergers generally play an important role in a free enterprise economy.” Together with Reagan’s FTC chair, James Miller, Baxter placed consumer welfare at the center. The two men rewrote the industrial policy of the FTC, shifting it from “protect the economy from economic dictatorships” to “protect big corporations because they know what they are doing.” They wiped out the old practice of presumptively opposing certain mergers. Miller also directed his staff to be less adversarial with business, brought fewer cases, cut his own budget, and centralized control within the FTC to advance his own ideology equating big business with maximal market efficiency and consumer welfare.

Reagan, Meese, Miller, and Baxter worked swiftly to dismantle most other federal efforts to advance antitrust actions, and they succeeded. Baxter redirected the entire agency infrastructure toward consumer welfare—away from workers, small businesses, and democratic concerns, and away from enforcement generally.

Reagan also transformed an agency created by Jimmy Carter into a major deregulatory juggernaut. The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) carries out a mission every bit as Kafkaesque as its name. Virtually all executive branch agencies would now require OIRA approval for new rulemaking, and Reagan tasked the formerly obscure agency with evaluating all regulation on a cost-benefit metric, even in cases in which the agencies’ enabling legislation did not require any such analysis. And that mandate has had exactly the effect Reagan intended: making rulemaking slower, giving a greater administrative role to corporate lobbyists, and thwarting the will of Congress, by adding this potent requirement to justify all agency action in terms of prospective adverse market impacts.

We have been living in the industrial policy built by Reagan, Meese, Baxter, and Miller ever since: No later president has changed the fundamental orientation of all industrial policy toward consumer welfare, or relinquished the Reagan White House’s pronounced reticence about opposing mergers, or dissented from the worldview that big business is efficient and “intervention” is bad.

What would the opposite of Reagan look like? What would a trust-busting Biden FTC do? Sandeep Vaheesan, a lawyer and scholar at the Open Markets Institute and the leading proponent of the use of regulatory powers to achieve fairness, says the first step is openly rejecting the Reagan philosophy, and instead embracing a structuralist approach, using bright-line rules to define and rein in monopoly concentration and looking at consolidation with suspicion. One early test of a new and robust approach to antitrust on Biden’s watch will be in book publishing: Last November, Penguin Random House announced plans to acquire Simon & Schuster, creating a mega-publisher that would control one-third of the U.S. market for books. This scale of consolidation could create the same top-down chokeholds on the free flow of printed information that the big four’s rise has done within the digital sphere.

But beyond individual cases, here’s a draft blueprint of some of the rules a Biden FTC could promulgate under Vaheesan’s approach:

- The FTC could ban employers from forcing workers to sign noncompete clauses that make it difficult to shift jobs, and effectively impossible to negotiate for better benefits. Noncompete agreements suppress wages at a time when wages are the key to economic recovery and survival.

- The agency could issue a rule banning exclusive agreements by dominant firms. These “agreements” lead to scarcities within supply chains, because they mandate things like manufacturers and suppliers limiting who they can contract with—a special problem in a pandemic—and farmers being kept from repairing their own tractors.

- FTC officials could restore the commonsense model of merger review developed in the Kennedy-Johnson era, under which company mergers in high-density markets were presumptively challenged because they were likely to lead to monopoly abuses. The agency could create bright-line rules for guidance.

- The FTC can institute rules that recognize the growing evidence of big companies suppressing wages by having so much market power, and promulgate rules using labor markets as a way to identify consolidation. Or, as a minimum requirement to approve a merger, the FTC could require card-check—i.e., simple opt-in systems to establish collective-bargaining units in most workplaces—to enable unionization at any acquired firms.

- The FTC could outlaw exploitative and predatory franchise terms, and prohibit franchisors from disrupting or abolishing collective-bargaining relationships of franchisees with their own workers.

And the FTC is just one case in point—the president’s rulemaking authority to create anti-monopoly policy runs throughout the executive branch. Biden can take away OIRA’s veto power over rules, and enable agencies to do their statutorily mandated jobs. Biden should direct the new secretary of agriculture to use the agency’s authority under the Packers and Stockyards Act to ban abusive contracts between monopolists and farmers. He should direct the new secretary of transportation to overturn an existing rule that gives airlines antitrust immunity. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has enormous powers, but big fossil fuel interests have largely reduced it to a rubber-stamp captive regulator that acts chiefly on their behalf. However, things don’t have to be that way: FERC rulemaking could structure the energy sector so as to boost decentralized sources of power, green technologies, and more robust supplies of renewable energy. The Department of the Interior can use rulemaking to govern how the enormous swaths of federally owned land are used for responsible and decentralized green economic development. The Department of Defense can issue new contracting guidelines that forbid contractors to have too many contracts, forcing decentralization in a highly concentrated defense contracting industry.

Creating an antitrust regime that undoes the damage of the Reagan legacy also means ensuring that anti-monopoly policy prioritizes those industries in which market concentration has exacerbated racial disparities of wealth and power. Forty years of runaway mergers have meant 40 years of destruction of Black-owned businesses, 40 years of decreased working-class power, and 40 years of franchise abuse, with franchise operations heavily concentrated within the Black, Latino, and Asian American communities. It’s also meant four decades of big monopolies using lobbying power to push for voter suppression and dilution. The American Legislative Exchange Council—the state-level network coordinating the racialized war on ballot access—isn’t funded by your local funeral home, but rather by a battery of big corporate interests headlined by the Koch brothers’ energy and commercial empire. As the think tank New Consensus recently recommended, Biden can use existing powers within the Federal Reserve System to direct lending toward the small and medium-size businesses and communities that most need it.

Of course, when people think of trust-busting, they don’t think of rulemaking, or using the Fed’s lending facilities, but of the landmark federal prosecutions of Standard Oil, IBM, AT&T, Microsoft, and the like. Columbia Law professor Tim Wu has persuasively argued that these big cases are themselves a key part of industrial policy, because they shake up highly concentrated markets, spur innovation, and let the forces of capital know that monopolization is not a safe bet. The policy upshot of these market disruptions, Wu argues, is to push capital to the edges of the market, further decentralizing power.

With the antitrust arms of the federal government poised to shake off four decades of Reagan-induced hibernation, there’s no shortage of similar antitrust actions waiting to be brought. For starters, Biden could double down on the Google lawsuit brought in a rare burst of antitrust vigilance by Trump’s Justice Department, and set out to dismantle the self-dealing schemes of Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple. But the Biden administration has to quickly show leadership outside of big tech, too—in hospital consolidation, big pharma, and agriculture.

Bringing high-profile antitrust cases against today’s concentrations of corporate power is the fight that Americans from all backgrounds desperately want their government to carry out on their behalf. These cases are also a form of stimulus. Economists Hal Singer and Marshall Steinbaum recently made this argument in a post on the University of Chicago Booth School of Business blog ProMarket. “By attacking power imbalances,” they wrote, “competition policy can steer income to workers and independent merchants who are more inclined to spend.”

When the government went after AT&T in the 1970s for its monopolistic practices, the settlement of the case resulted in a huge spur to innovation, a stimulus for the telecommunications industry, and a redistribution of wealth all at once.

Even the act of bringing a lawsuit can create a powerful stimulus. Last November, after Epic Games filed suit against Apple for antitrust violations, the computer giant swiftly lowered the licensing fee it charges vendors from 30 percent to 15 percent for smaller-scale developers. That marked an immediate infusion of cash into the coffers of small developers—money that can go to medical bills, food, and other outlays sure to spur economic growth in local communities. Now imagine the stimulus effects of similar lawsuits—except backed by the full weight of the Department of Justice.

Using the same theory that Epic used, the Justice Department could sue the global tractor manufacturer John Deere for forcing farmers to use its repair services. Department lawyers could launch a major investigation into how Amazon uses the choke point of its platform to direct business to sellers who use the gargantuan retailer’s suite of advertising services and its shipping and warehousing service.

Amazon is extremely sensitive to public pressure. When Bernie Sanders attacked the company for its scandalously low wages, Amazon promptly enacted a wage increase for its (now) million-plus workforce. After it elected to open a second corporate headquarters in Queens, New York, it revoked the plan—together with billions in public subsidies underwriting it—rather than face ongoing protests and public inquiries. So in all likelihood, a simple antitrust filing from Biden’s Justice Department could be enough for Amazon to suspend its ancillary services racket, where it effectively forces sellers to use its fulfillment service, by rewarding those who use them with higher search results—a mechanism that ultimately takes money from small businesses. Recent research by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance showed that Amazon keeps, on average, 30 percent of each sale made by an independent seller. There are more than two million active Amazon sellers. So reducing an average seller’s payments from 30 percent to, say, 10 percent of sales cost would be a major, direct boost to sellers. And that stimulus effect would reverberate widely, since those sellers hire workers and purchase consumer goods throughout the country.

If Biden’s Justice Department takes an across-the-board, aggressive approach to the problem of monopoly concentration, it could prompt bad actors atop the economic food chain to relinquish their abusive behavior—another reordering of priorities that would leave more money on the table for the businesses and workers.

For all the promise of reinvigorated antitrust actions, the challenges are enormous. The consumer welfare model of merger promotion pioneered in the Reagan years has taken over the courts. In a critical series of rulings, the Supreme Court has made it much harder to bring cases, changing the standards of proof, distorting the meaning of monopoly, and relying on economic theories with no grounding in statutory history.

Documenting the baleful impact of this misguided legal reasoning was a key aim of the Cicilline report, and Biden has to use the bully pulpit of his presidency to enact a major raft of legislation to overturn this body of bad statutory interpretations. In the meantime, Biden cannot shrink from bringing cases. There’s no legal or economic rationale for another unilateral government retreat in the face of growing monopoly power. Even less is there any cause to follow the dismal precedent set under Biden’s former boss, Barack Obama, and suspend continued and vigorous antitrust prosecutions out of fear of industry backlash.

And this poses an additional challenge: For Biden to take this path with any conviction, he’ll have to admit that Obama’s FTC and DOJ did a bad job. Biden ran his campaign on a very explicit framework of nostalgia for the Obama years, and his transition has so far maintained that tone. “America is back!” is how he announced his incoming national security team—eschewing the opportunity to suggest, let alone declare, a Biden doctrine, he chose instead to broadcast, both with personnel and language, a continuation of the Obama doctrine.

But Biden can’t declare he’s bringing America back again and have any credibility with workers and small businesses crushed by monopolies. Obama’s antitrust failure with farmers is well known in rural communities, and even managed to puncture the media’s usual cone of silence enveloping questions of antitrust enforcement.

Under Obama, traditional private-sector mergers continued in an unchecked wave, concentrated corporate power increased throughout the American economy, airline prices rose, insulin prices rose, wages stagnated—and big tech gobbled up hundreds of companies without any serious merger challenges. The Sherman Antitrust Act lay dormant, as the DOJ brought no major monopoly cases during the eight years of Obama’s presidency.

A forthcoming 150-page report from American Economic Liberties Project, gently called “Courage to Learn,” goes into painful detail on this legacy, examining the sector-by-sector regulatory failures of the Obama White House amid steadily advancing corporate consolidation.

The professional pride of the lead policymakers called out in such reports is not a trivial barrier, given that they are now sitting atop perches at many of the fanciest universities in the country. If, as Jeff Goldblum told us in The Big Chill, rationalizations are more important than sex, then the deep investment in rationalizing their refusal to stop monopolistic growth and abuses presents a formidable barrier to change.

And when the momentum of professional self-justification is combined with cash incentives, the barriers become tougher still. Former Obama DOJ economist Fiona Scott Morton has styled herself a devotee of FDR-era trust-busting, even naming the center she now runs at the Yale School of Management after Roosevelt’s crusading trustbuster Thurman Arnold. But she has claimed she favors greater antitrust enforcement while opposing breakups. Her aggressive support for the creation of a new agency, as opposed to the deployment of long-latent regulatory powers, seems like a status quo maneuver aimed at sidestepping prior regulatory failures. It’s a bear hug of reform designed to kill it. Not for nothing has Scott Morton taken undisclosed amounts of consulting cash from Amazon and Apple, according to reporting from Bloomberg News. Berkeley professor Carl Shapiro, also a former DOJ economist who later served on Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, now pretends to denounce the scourge of concentration while assailing anyone who dares to challenge the Reagan consumer welfare standard, and refusing to apologize for the DOJ failures. He’s been a paid consultant to Google.

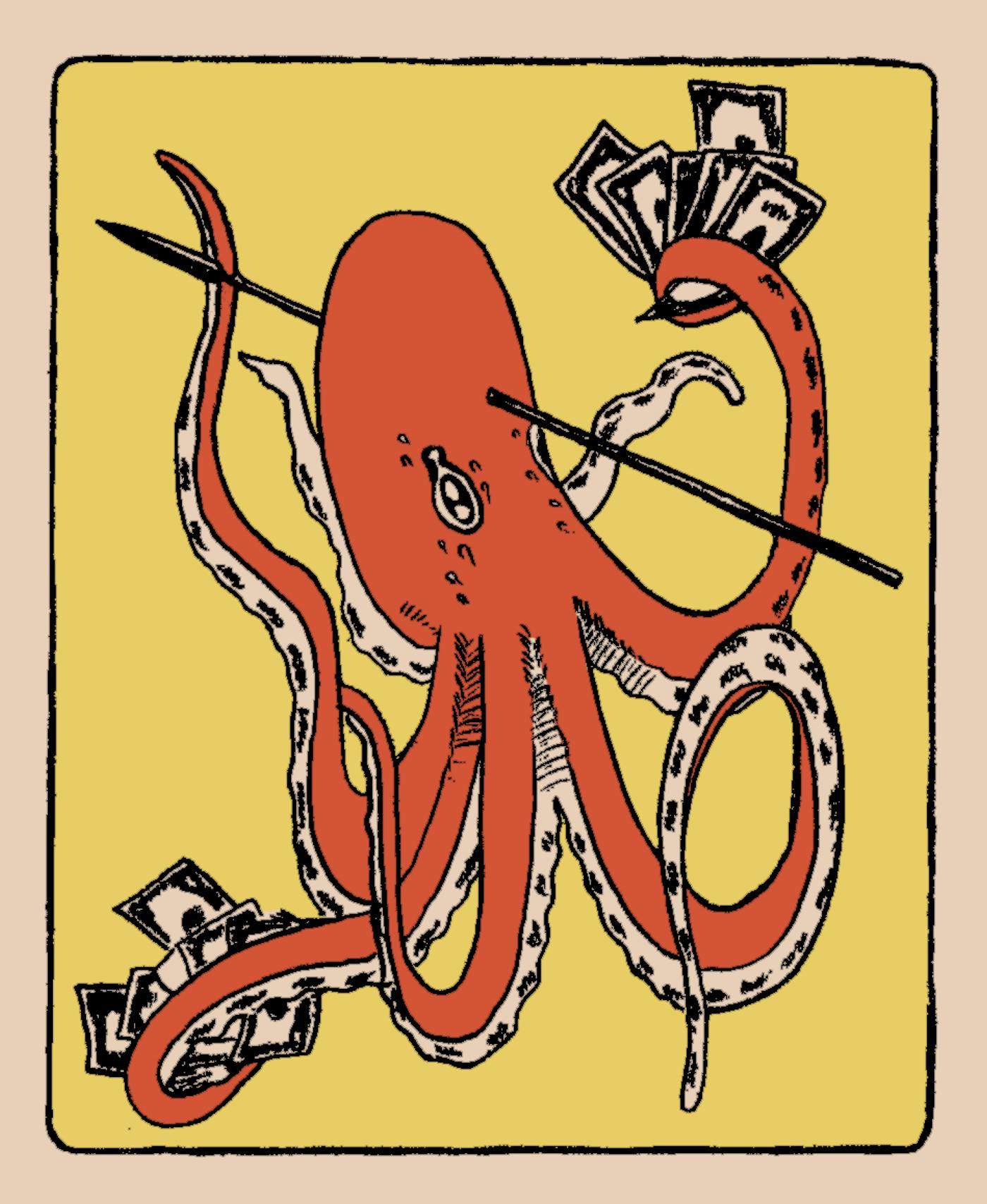

There’s an epidemic of big tech money in antitrust economics circles: Amazon, Google, and the rest know the power of funding high-profile enforcers, and they have flooded the field. (Google alone funded 329 public policy papers between 2005 and 2017.) The same market-capture strategy is also overtaking the nonprofit sector: Public Knowledge, an ostensibly progressive D.C. think tank, is supported by “$25,000+” from Amazon, Google, AT&T, Netflix, T-Mobile, and the Consumer Technology Association. Concerned citizens are left guessing what the “+” means.

The recipients of all this big tech largesse naturally deny that these financial entanglements influence their findings in any way. And, to be fair, they probably are totally unaware of how that happens, because crude quid pro quos wouldn’t work for them. At the same time, of course, any defiance of big tech mandates in these rarefied policy circles would fly in the face of history, received wisdom, and human nature.

It’s no surprise, then, that American voters are already sounding the alarm on corporate influence within the Biden Cabinet, with around 60 percent of respondents in a recent Data for Progress survey saying a Biden administration led chiefly by corporate CEOs and lobbyists would undermine the president’s campaign messaging—and 68 percent saying that nominees with such a monopoly-friendly résumé should be held up by the Senate.

Such sentiments again reflect the lived experience of many Americans over the past generation of steadily advancing corporate power. While Obama stood still before this threat, the lead enablers of global monopoly did not. They have been amassing political clout and influence at levels never seen before in our country, even during the Gilded Age.

Scott Morton, Shapiro, and others still aligned with the big market players clearly want to be back in the driver’s seat, but their corporate gigs should make them ineligible—to say nothing of their past failures to act. As Shaoul Sussman, a plaintiffs-side antitrust lawyer (and my former law school student), says, it would be “like letting a pilot fly a plane after a crash—they blame the engines (which might be true) but reject any human error. You can’t let them into the cockpit again without first confronting and analyzing the reasons for their failure.”

The good news is that there are brilliant, experienced lawyers who are not entangled in the tentacles of monopoly money, or the tentacles of Obama-era rationalization. FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra, Columbia Law professors Tim Wu and Lina Khan, and Brooklyn Law professor Frank Pasquale all have the background and expertise to lead in this moment. Jonathan Kanter, a private attorney with decades of plaintiff-side antitrust experience, would be an outstanding hire. So would Sally Hubbard, a nationally recognized antitrust expert who cut her teeth in the New York attorney general’s office. Biden should put people from labor and small business into the policymaking apparatus, instead of letting industry-aligned economists and technocrats fall in line behind an agenda to shore up the unsustainable status quo.

The real reason Biden should act is not that it is good politics, or that he has the vast regulatory state suddenly at his disposal, but because the crisis of entrenched corporate power is at bottom a mortal threat to a fair society and anything resembling a functioning democracy. As FDR said in that speech, the “new industrial dictatorship” is incompatible with democracy, and when “opportunity [is] limited by monopoly,” private enterprise becomes “privileged enterprise, not free enterprise.” People are suffering because big pharma demands outrageous prices, big ag and big tech steal their wages, and their communities are hollowed out by the great sucking sound of Wall Street’s private equity combine. And they are mad because they are also getting shut out of the democracy that is supposed to stop this from happening.

Joe Biden has wanted to be president his entire life, and when he set out on this third journey to the presidency, he had a vision: restore the America he knows. But he can’t. There’s no going back to Kansas—or Scranton, as the case may be. But there is a clear path to a more viable and equitable future—a unique chance not merely to build back better, as his campaign slogan had it, but to ensure that the American economy, like the government Biden is poised to lead, actually works for the American people.