As 2021 comes to a close, Democrats are in an unenviable—in fact, downright brutal—position. Gubernatorial elections in Virginia and New Jersey suggest a red wave is coming in next year’s midterms no matter what they do. Still, congressional Democrats haven’t shown much ability to do things that might help some. Sure, they did ultimately pass a $1 trillion infrastructure package, but the budget reconciliation bill they’ve been working on for months—the Build Back Better Act—seems all but dead. Whatever you think of the utility of the political approach known as “popularism,” it’s clear that Democrats struggle to do anything—even (and perhaps especially) very popular things.

The overriding focus on Build Back Better has been a political disaster for the party and the president. Yes, the provisions in the bill are broadly—and in many cases exceptionally—popular. But Democrats’ inability to actually finish the bill has meant that attention has understandably focused on the many popular things they have cut out of it and, inevitably, the fact that the party is in disarray. Whether or not Build Back Better gets done in 2022—and whether or not voters give them credit for passing a transformative social spending bill—Democrats need to do more to convince voters to keep them in power in both the midterms and the next presidential election.

One issue is marijuana policy. “You would think that President Biden would embrace legalization, considering where his constituents are on this issue,” Chris Lindsey, legislative analyst at the Marijauna Policy Project, told me. Per a recent Pew survey, 60 percent of Americans favor full legalization, while 31 percent favor legalizing marijuana for medical use only, meaning that a whopping 91 percent of Americans are in favor. And while several states have relaxed laws or fully legalized weed, the federal government is trailing. “It’s not a question of when,” Lindsey told me. “It already happened. Two out of three [states] do allow access: They allow people to grow it, cultivate it, process it, and sell it to a certain subset of residents in their state that have qualifying medical conditions. There are a lot of states that have expanded it to allow all adults access. Whether or not the federal government catches up is really a question of, when is the federal government going to get into the business of regulating? That’s really the issue.”

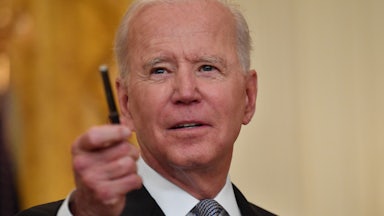

Joe Biden is hardly an enthusiast for relaxing drug laws; he referred to marijuana as a “gateway drug” as recently as 2019, though he quickly walked it back. And yet his administration has done less and more slowly than he indicated on the campaign trail, when he made modest promises to decriminalize marijuana and provide funding for states to expunge the records of nonviolent offenders convicted of marijuana-related offenses. Not only has his administration made little progress on the policy front, it has also been reactionary in terms of staffing: Five White House staffers were fired in March after it emerged, during the vetting process, that they had used marijuana.

But Biden’s antiquated attitudes toward marijuana—shared by some older Democrats who worry about being labeled as soft on crime or even as hippies—are increasingly out of step with the mainstream. Biden and his party both are in need of political wins, and relaxing marijuana laws—or fully legalizing the drug—is extremely popular. It’s also increasingly bipartisan. A majority of both Democrats and Republicans now favor legalization. Many of the leading political voices on the issue in recent years are Republicans: Nancy Mace and David Joyce, both Republican congressmen, have bills relating to marijuana legalization and expunging the records of past offenders.

For Democrats, this could mean that they would be unlikely to reap the sole political rewards for any efforts on marijuana policy. Lucky for them, many in the party—including the president himself—are desperate to notch bipartisan wins. Passing a bill in Congress would almost certainly garner sizable support from Republicans as well as Democrats and possibly even more than the infrastructure bill that was signed into law last month. There are several options. The most promising is the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, a bill being pushed by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Cory Booker, and Ron Wyden that builds on a legalization bill passed by the House last year. (There are also several other, less ambitious legalization bills floating around, including the MORE Act.) Unfortunately, a frosty reception from some Democrats, a lack of enthusiasm from Senate Republicans, and the continued existence of the filibuster means that these efforts have stalled out—for now. The bully pulpit, plus the midterm elections, could revive them.

There are other options, however. Mace is pushing a bill that would decriminalize marijuana, while Joyce has one that would reform the federal government’s incredibly outdated marijuana policies. Given the general sense of inertia in Congress, there are other less far-reaching but still important things the Biden administration could do. The Cole memo, issued by Eric Holder in 2013 and revoked by Jeff Sessions five years later, instructed U.S. attorneys not to enforce federal marijuana laws. That memo could be reinstated and even expanded to other departments. Biden could offer clemency to people currently imprisoned for nonviolent cannabis-related offenses and pardons for them and those who have been released.

All of this would be better politically and morally, and in policy terms, than what Democrats are doing now. “You would think that President Biden would embrace legalization, considering where his constituents are on this issue,” Lindsey told me. “There’s really no question [about] the level of support that they have, and yet the president seems to be AWOL.” After a year ending with political and legislative inertia—and with Biden’s tanking poll numbers, particularly among young people—marijuana policy would be the perfect place to start.