In 1937, America’s first drug czar, Harry J. Anslinger, published a feature story in The American Magazine titled “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth.” The article featured a vicious ax murderer with a drug problem. “An entire family was murdered by a youthful addict in Florida,” Anslinger wrote. “When officers arrived at the home, they found the youth staggering about in a human slaughterhouse. With an ax he had killed his father, his mother, two brothers, and a sister. He seemed to be in a daze.” At the time, Anslinger was the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the institution that preceded the Drug Enforcement Administration. The same year, he drafted legislation that effectively made cannabis illegal at the federal level.

Anslinger had plucked the story of the ax murder from his “gore files,” a collection of 200 grisly homicides committed by alleged consumers of cannabis. Keeping a list of supposed crimes committed by a scapegoated group is a tried and true strategy of strongmen waging a battle for hearts and minds. In 2017, for example, President Trump announced that his team would publish a weekly report of crimes committed by immigrants, singling out Mexicans. (Although it should be noted that, like many of Trump’s projects, this one appears to have fizzled out.) Gore files and the like are also useful in stoking moral panics about stigmatized behavior. The Prohibition era teemed with lurid anecdotes about murderous drunken rages.

The encroaching specter of mass legalization of cannabis has triggered a strange reprisal of the alarmist themes of Anslinger’s assault on the plant over 80 years ago. More curious still, our celebrated latter-day apostle of Anslingerism—the thriller novelist Alex Berenson—has been embraced by a credulous mainstream and liberal press, which gets routinely lambasted in another redoubt of culture war combat as faithless, elite-decadent merchants of “fake news.”

Anslinger was himself a font of fake news. Historians who have studied the murders that he deployed in his anti-cannabis campaign discovered that he ignored crucial facts, including the troubling psychological history of the ax murderer in “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth.” For Anslinger, cannabis was the culprit, never mind the particulars. As sociologist Howard Becker argued, culture warriors like Anslinger are a potent illustration of “moral entrepreneurship,” a term he coined in his seminal 1963 book Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. “The moral crusader is a meddling busy body, interested in forcing his own morals on others,” Becker explained. “The existing rules do not satisfy him because there is some evil which profoundly disturbs him.”

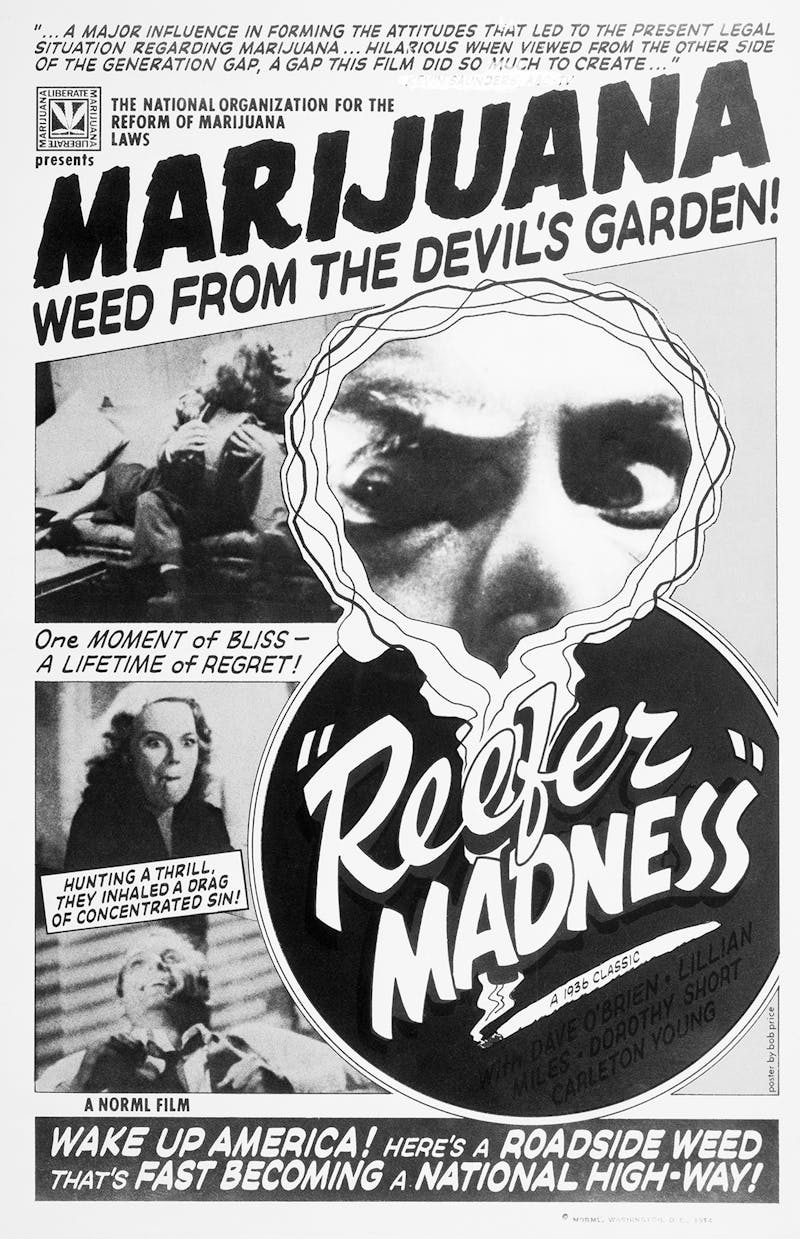

In Anslinger’s case, the evil was clear. “The officers knew him ordinarily as a sane, rather quiet young man,” Anslinger wrote of the murderer. After smoking weed, “he was pitifully crazed.” That was typical of how the scourge of “cannabis-induced psychosis” was described in speeches, congressional hearings, yellow journalism, and exploitation cinema. The notorious 1936 propaganda film Reefer Madness, for example, depicted housewives and other stable, healthy people going mad after smoking. This vast communications apparatus was dedicated to transmitting a single claim: Far from a benign plant, cannabis causes dangerous, unpredictable side effects on the psyche—chief among them, a violent urge to senselessly kill.

One might imagine that in this day and age we would have grown immune to moral entrepreneurship in the context of cannabis, now that a movement has begun to unravel Anslinger’s legacy. But in tandem with the momentum toward national legalization of cannabis, a new crop of moral entrepreneurs, led by Berenson, have stepped forward to enforce the crumbling status quo. Instead of meddlesome bureaucrats, these are high-profile writers, serious people, who are raising a new alarm about the dire social and health ramifications of legalization. In a last-gasp effort, some are even deploying Anslinger’s patented moral-panic strategy—sensationalizing gruesome homicides as evidence that cannabis really does create psychotic murderers out of unsuspecting weed smokers.

Is your freedom to consume cannabis really worth the apocalypse of violence that will accompany it? Surprisingly, this message from 1937 is gaining serious traction in 2019.

By the time Anslinger introduced his new federal restrictions in 1937, all 50 states had banned the substance. The reverse process is swiftly playing out before our eyes. In 1996, California became the first state to legalize cannabis for medicinal purposes. Within two decades, 33 states had followed suit. In 2012, Colorado and Washington legalized cannabis for recreational use, without any need for a doctor’s approval. Today, 10 states, as well as Washington D.C., have to various degrees legalized recreational cannabis. New York, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Illinois, among others, are all flirting with legalization or considering relaxing their cannabis laws in the upcoming election cycle. In theory, as more and more states lift their decades-old restrictions, the momentum will force the federal government’s hand toward blanket legalization.

America has come a long way since the days of Anslinger. Several contenders seeking the 2020 Democratic nomination—Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand—have co-sponsored the Marijuana Justice Act, a bill championed by presidential hopeful Cory Booker that would remove cannabis from the Controlled Substances Act, effectively ending federal prohibition. The legalization push also happens to be bipartisan. When former Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner joined the board of a cannabis holdings company, he told the press that his views on the drug have “evolved.” Conservative-leaning libertarian think tanks, like the CATO Institute, have also advocated the end of pot prohibition.

Popular opinion points in the reformers’ direction, with 62 percent of respondents in a recent Pew Research Center poll favoring legalization. But in many organs of policy debate, a backlash is mounting. After years of soft coverage on cannabis, several writers from traditionally liberal outlets such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Mother Jones, and The Marshall Project have slammed the brakes. Their renewed skepticism toward legalization hovers somewhere between calls for more research and new worries that cannabis does produce psychotic symptoms in otherwise healthy people, suggesting that consumers could be just one edibles-munching episode away from committing monstrous violence on their family and neighbors. These critics also argue that activists, in their effort to legalize cannabis, downplay and hide the plant’s true harms.

Most peculiar among this crowd of left-leaning moral entrepreneurs positioning themselves as contrarian Davids fighting the libertine hive-mind Goliath is Berenson, author of the (unironically titled) manifesto against cannabis, Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness, and Violence. (Tell Your Children was the original name of Reefer Madness.) In an interview with The Marshall Project, Berenson explained the title: “I expected I would face serious backlash for this book and instead of running from it I decided to lean in.” In the same way that recently arrested Trump consigliere Roger Stone enjoys being a villain, Berenson clearly relishes triggering people he dubs “advocates” by tapping into an old vein of drug scares that was thought to have dried up years ago.

The book’s premise is simple enough: “Marijuana causes psychosis. Psychosis causes violence. The obvious implication is that marijuana causes violence.” Instead of maintaining merely that X causes Y, Berenson added a step: X causes Y, and Y causes Z, so X can be said to cause Z. Because cannabis lives next to heroin and LSD in the dusty attic of Schedule I substances—a category for drugs with a high potential for misuse and zero established medical value—researchers have had a difficult time actually studying it. Berenson fills the absence of evidence—a cognitive nether zone in which arrows of causation can be made to point every which way—with heinous acts of violence committed by cannabis users. Aided by a savvy PR offensive from his publisher, Berenson hurled Anslinger’s dark imagination back into the discourse on legalization.

The book opens with a bracing statement: “Everything you’re about to read is true.” We then move briskly to the story of a 37-year-old Australian woman named Raina Thaiday, who stabbed eight children to death. Thaiday was schizophrenic, and Berenson writes that she had used cannabis since the ninth grade. The judge ruled that she had no capacity to understand what was happening, but also found, as Berenson points out, that “Thaiday’s illness was no accident. Marijuana caused it.” He laments that the brutal crime attracted little interest, since it was “proof of hidden horrors present and worse to come.” Much worse, indeed. In Part Three of Tell Your Children, titled “The Red Tide,” Berenson recounts numerous homicides that he claims happened because of pot, painting an apocalyptic future where this nightmare fuel is legal and civilization is undone by cannabis-inspired acts of violence.

“Really, this book could’ve been written by Harry Anslinger,” said Isaac Campos, a historian at the University of Cincinnati. “He’s pulling straight from the old-school playbook. But it’s been a couple decades since anybody would listen to that.”

But people are listening. Tell Your Children received favorable coverage in nearly every major media outlet, followed by excerpts in The New York Times (Berenson’s alma mater) and The Wall Street Journal arguing that states with recreational laws on the books saw “sharp” increases in the prevalence of violence. The backlash Berenson predicted was indeed fierce, with scathing critiques appearing in New York, Vox, and Vice. But soon the calm and measured refrains of puzzled both-sides-ism overtook the media scene, and Berenson was able to set up entrepreneurial shop in a noncommittal news-from-nowhere vacuum. A master of keeping his name in headlines, a week after The Marshall Project published a softball interview with Berenson, it ran a “digital roundtable” featuring experts criticizing Berenson’s claims, and Berenson responding. New York also published a follow-up giving Berenson the opportunity to defend his claims.

On Twitter, he poses as a self-satisfied devil’s advocate, crushing the Libs with logic, perpetually goading his most high-profile critics to publicly debate him. When the book was released, Malcolm Gladwell described Berenson in The New Yorker as having “a reporter’s tenacity, a novelist’s imagination, and an outsider’s knack for asking intemperate questions. The result is disturbing.” Tucker Carlson praised Berenson for being courageous. “You got a lot of guts to write something like that given the world I’m sure you live in. I admire that,” Carlson said to a smirking Berenson. “I hope it sells a lot.”

The renewed skepticism about legalization has now traveled outside of Twitter debates and Fox News and into Democratic talking points. On February 4, a few weeks after Tell Your Children’s initial media blitz ran its course, Senator Dick Durbin said his home state of Illinois should not rush toward legalization, pitting him against the newly elected Democratic Governor JB Pritzker. Explaining why he wanted to slow-walk legalization, Durbin told local press to read Gladwell’s piece in The New Yorker. He went on to say that he’s concerned about states with recreational laws on the books seeing an “increase in traffic accidents; certain mental health conditions seem to be more prevalent in those states. These are all legitimate clinical questions that should be asked and tested.”

Berenson was thrilled. “Wow. Illinois @senatordurbin mentions @gladwell’s piece and says his state should not rush to legalize recreational cannabis,” Berenson tweeted. “I can’t remember the last time a prominent Democrat urged caution on legalization. Happy to get you a copy of TYC, Senator!”

One reason the knowledge Durbin is seeking isn’t readily available is the same reason Berenson is able to continue recklessly equating pot use with violent schizophrenia: because it’s difficult to study the behavioral effects of Schedule I substances in any systematic way, especially when over 50 million people are already using it. Furthermore, Durbin had not actually flipped on the issue. In 2018, he’d been in favor of medicinal use, but opposed legalization for recreational use. But Berenson, aided by Gladwell and an effective media campaign, has renewed the argument that has stigmatized marijuana for decades: that it is a dangerous drug for both the people who use it and those around them. Children, especially.

Some of Berenson’s most notable critics are the very researchers he has cited as sources in Tell Your Children: Campos the historian and UCLA’s Dr. Ziva Cooper, one of the authors of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s landmark report on cannabis, which Berenson frequently refers to when arguing that cannabis causes psychosis. Together with other aggrieved Berenson sources, as well as the renowned neuroscientist Carl Hart, they have called out Berenson for cherry-picking their work and overstating risks found in the literature.

The science on cannabis has found correlations and associations between cannabis use and psychotic episodes. But the direction of causation remains an open question. With so many people already using cannabis, it’s odd that we’re not seeing a significant “red tide” of pot-induced slaughter. Unless, of course, you avidly watch Berenson’s feed, which has become a repository for bizarre homicides, such as a Pennsylvania mother who “killed her three-year-old in a psychotic rage” and “a married 33-year-old software engineer with no criminal history who inexplicably went on a shooting rampage.” It is a living, breathing gore file. Berenson’s Twitter feed exposes the statistical sleight of hand that runs throughout his book. The anomalies and inexplicable occurrences at the very tail end of the bell curve are framed in such a way as to be occurring right in the center, where tens of millions of users reside. Berenson does not offer any count of just how many of these 50 million consumers might be wreaking violent mayhem while high.

It’s possible, in addition, that people suffering from hallucinations and mental torment reach for substances like cannabis to assuage their symptoms. In a 2016 peer-reviewed analysis of the literature, Hart and his colleague Charles Ksir wrote, “The evidence leads us to conclude that both early use and heavy use of cannabis are more likely in individuals with a vulnerability to psychosis.” According to the National Academies report, “The relationship between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder, and psychoses may be multidirectional and complex.” And in response to Berenson’s New York Times book excerpt, Cooper tweeted, “We did NOT conclude that cannabis causes schizophrenia.”

Berenson responds incredulously to such criticisms, and dismisses the people mounting them as “advocates” bought out by Big Pot. When, for example, an academic challenged Berenson for wrongly using statistics to document a correlation between pot use and violent behavior, Berenson tweeted a two-word rejoinder: “cute graphs.” When he was asked to comment for this article, he tweeted a screenshot of my email and mocked me for asking an “all-time stupid question.” In an email response (which he also screenshot and tweeted), he said his book had galvanized people who have concerns about marijuana and have been “gaslit” by Hollywood and the elite media.

Sociologist Howard Becker classified moral entrepreneurs into two distinct categories: rule creators and rule enforcers. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who famously said, “Good people don’t smoke marijuana,” is, or at least was, both a rule enforcer as U.S. attorney general and rule creator as a senator of 20 years representing Alabama, where black people are four times more likely than whites to be arrested for possessing cannabis. (Berenson has an explanation for such atrocious disparities: “Black people are more likely to develop cannabis use disorder,” he writes in his book. “They are also more likely to develop schizophrenia—and much more likely to be perpetrators and victims of violence.” Or to translate the coded language here into plain English: Cannabis makes them more violent than us.)

Unlike Anslinger and Sessions, Berenson has no authority to write and enforce laws. But he can use his influence to become a kind of norms enforcer. Anslinger’s campaign wouldn’t have been possible without the help of the yellow journalism of his day, and Berenson has similarly relied on the megaphone of social media and the press to worm his message into the ears of actual rule creators and enforcers.

“The ensuing moral panics not only legitimize the efforts of moral entrepreneurs who push political and policy agendas,” Joy Kadowaki, a sociologist and lawyer, said about the type of campaign Berenson has created. “But they also sell movie tickets (Reefer Madness), magazines (Anslinger’s “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth”), and books (Berenson’s Tell Your Children).”

Meanwhile, Berenson has been tweeting at high volume, dissecting every morsel of media coverage and letting everyone know when a new batch of books is ordered up by his publisher. When he isn’t goading high-profile critics into debating him, Berenson is betting money that readers won’t be able to find a single error in his book. Dave Levitan, a freelance science journalist, took up the bet and found several factual errors and misleading statements. At Levitan’s behest, Berenson donated $200 to the ACLU, which is dedicated to seeking justice for communities of color disproportionately affected by the War on Drugs.

In 2019, few would argue that Anslinger’s Reefer Madness campaign was anything but propaganda. So why is Berenson getting away with it now? “Because the context is right,” Kadowaki said. “As marijuana use is normalizing and as dispensaries become a visible part of the landscape across the United States, Berenson has seized the opportunity to highlight this major cultural shift by playing into our last remaining fears.” She added, “He’s playing on a time-proven, albeit tired, tactic of the mass media: peddling fear to sell copies.”

And even more unsettling than Berenson’s alarmism about marijuana, she notes, is his willingness to exploit the stereotypes associated with mental illness. The science shows that people who are receiving treatment and services for a mental illness are no more violent than the population at large. The tragedy is that they’re more likely to harm themselves. “There are studies that show heavy marijuana use has the potential to be a risk factor in triggering a first episode of psychosis, however, this correlation does not imply causation for violence,” The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) told me in a statement. Berenson plows through cautious interpretation of the evidence, relying instead on the bloodiest anecdotes.

No one can truly know what motivated Berenson to write his book. A proven frontlist genre writer, maybe he just knew it would be lucrative. He already admitted to knowing it would generate a massive backlash, giving him a leading role as an “intemperate” and “unfashionable” contrarian—a lucrative gig in the anti-P.C. swamps. He also could genuinely be motivated to prevent a massive “red tide” of cannabis-induced violence. Then again, so was Anslinger.