D.H. Lawrence understood early on that his calling was to divide readers and friends. He hated to be silenced but loved to be hated. “It’s either you fight or you die,” he wrote in a late poem, taunting his readers as the matador taunts the bull in the mesmerizing opening of his often hateable novel The Plumed Serpent.

It’s extraordinary how far he succeeded: what extremes of love and hate he has provoked. For decades after his death, every critic, almost every reader, had their opinion about Lawrence. Responding to his statement that his “great religion is a belief in the blood, the flesh,” they granted him power to redeem or defile the world. Some modeled themselves on his characters, using four-letter words, wearing brightly colored stockings, rejecting formal educations to follow Ursula’s calling in The Rainbow to become fully herself: “To be oneself was a supreme, gleaming triumph of infinity.”

Leading the case for adulation was F.R. Leavis, who praised Lawrence’s work as “an immense body of living creation” informed by an “almost infallible sense for health and sanity.” Among those ranged against him was T.S. Eliot, who suggested that given Lawrence’s “incapacity for what we ordinarily call thinking” and his “sexual morbidity,” his work could appeal only to “the sick and debile and confused.”

These arguments played out in court at the 1960 trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, where not just a book but a nation’s bodily life was on trial. And then they were taken up by the women. There had been disquiet before. In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir movingly described her distress at realizing that, despite Lawrence’s “cosmic optimism,” he “passionately believes in male supremacy.” But now Kate Millett turned Beauvoir’s ambivalence into something more angrily certain in her 1970 Sexual Politics, castigating Lawrence for propounding his “personal cult, ‘the mystery of the Phallus.’” Lawrence was toppled from the canon, and generations of English students (my own among them) got through English degrees without reading him. It was left to female novelists and iconoclasts to defend him. “He was fiery and flamy and lambent, he was flickering and white-hot and glowing—all words he liked to use,” wrote Doris Lessing. “Oh, but he’s a sister,” Angela Carter shouted out on TV, later explaining, with an insight that reveals who Lawrence can be in our own times, that she saw Lawrence as a “drag queen”: “The stocking covers a hairy, muscular leg.” Susan Sontag announced at one point that her whole project was to be a female D.H. Lawrence.

In her new biography, Burning Man: The Trials of D.H. Lawrence, Frances Wilson approaches Lawrence with the fierce spirit of argument that he has always attracted and required. The author of acclaimed biographies of Dorothy Wordsworth and Thomas De Quincey, Wilson is fully alive to his faults. This is a writer, she argues, who didn’t ask us to agree with him. He asked us to be stimulated, delighted, and outraged by turns.

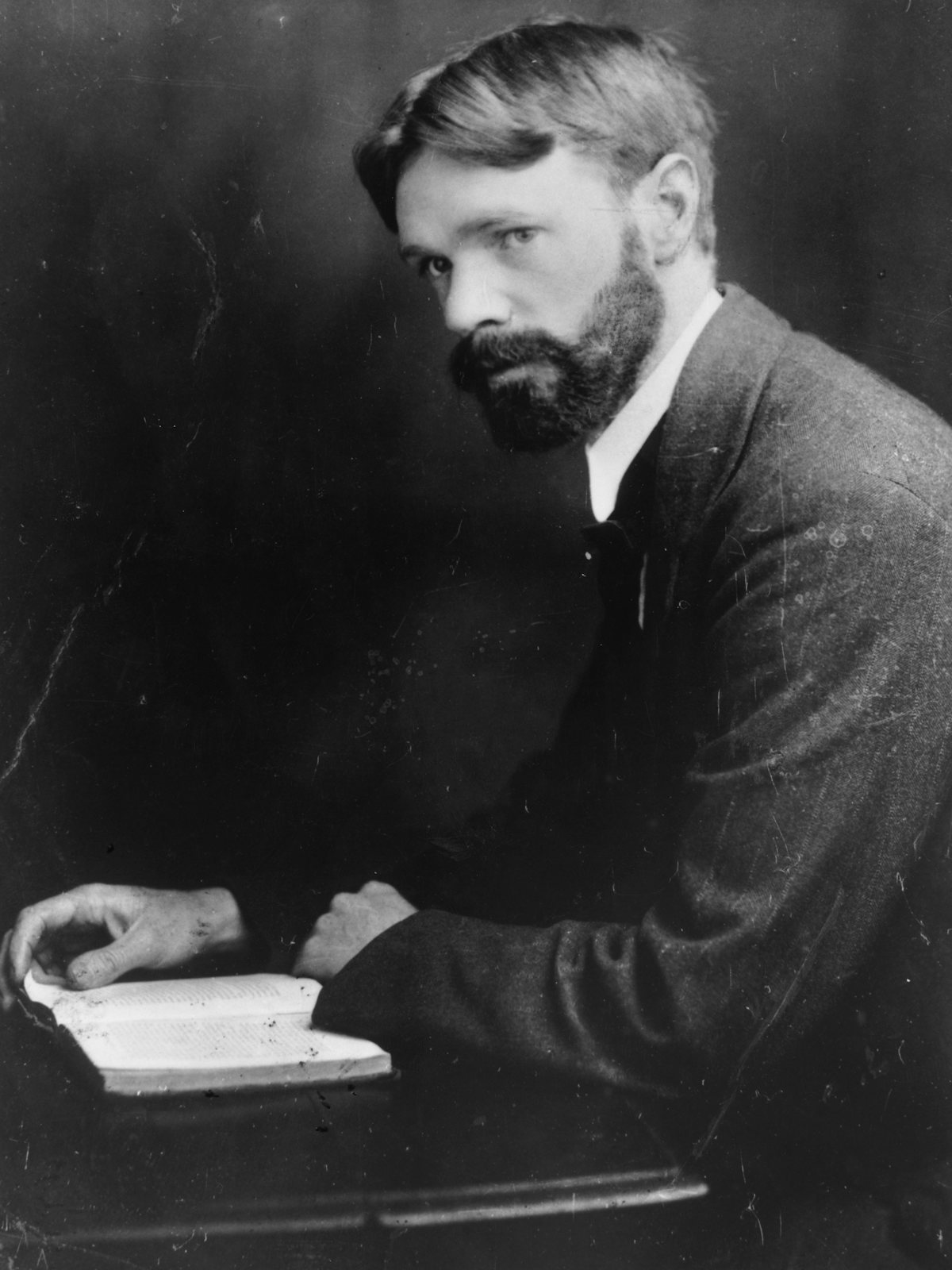

It wasn’t obvious in his much-mythologized East Midlands childhood that this divisive figure was who Lawrence would become. Born in 1885, “Bert”—from his middle name Herbert—was a sickly child, and his mother didn’t think he had long to live. The atmosphere of his childhood home, with his jolly but feckless miner father, his refined, long-suffering, son-smothering mother, infused his novels, poems, plays, and stories, and numerous biographies. There was a series of passionate, anxiously disembodied relationships with young women, followed by the fireworks of his meeting with Frieda Weekley, the married, older, aristocratic German wife of his college professor. They eloped to Germany in 1912, and there followed a year of fighting and reconciling that inspired the most brilliant sections of The Rainbow, Women in Love, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in which he is so wonderfully attentive to the minute-by-minute gyrations of love and hate within a couple.

The couple returned to England, embattled, Lawrence ready to publish Sons and Lovers and to fight Frieda’s husband for her children (though there was a side of Lawrence that wanted Frieda unencumbered). World War I broke out, dividing Britain from Germany and making him fear that rural life was going to be put to death by the machine age and intimate relationships swamped by the rising tide of nationalism. He described this in several letters as killing him: “my soul lay in the tomb—not dead, but with a flat stone over it, a corpse.” He and Frieda escaped to Cornwall, which he experienced as a resurrection. But the couple sang too many German songs, criticized the war too vehemently, and were sent away, pushed into the exile that came to define him.

The Lawrences wandered, often accompanied by loyal friends, from Italy to Germany to Australia to Ceylon to New Mexico to Mexico and back around the globe again. Each place seemed briefly as if it might be a home for life. But he didn’t like places he’d been ill in, and there were increasingly few where he had been well. And he didn’t like to put down roots. He suffered—this is one of the many insights in Wilson’s fascinating new biography—from claustrophobia, which Wilson sees as a fear inherited from his miner father.

During these years, Lawrence wrote prolifically in every possible genre, becoming, like Ursula, more himself, and getting into trouble as a result. The Rainbow was banned, Women in Love was for years unpublishable, his paintings were seized (too much pubic hair), his poems censored. He knew as he was writing Lady Chatterley’s Lover that it couldn’t be published. The anathemas added to his allure and became part of his own powerful vision of himself, captivating and enraging readers. Some invited him to live with them, among them Mabel Dodge Luhan, the American millionaire socialite living in New Mexico with a Native American lover, wanting to redeem white civilization. “I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had,” Lawrence later wrote of his arrival there in 1922. But they only stayed for three years. After Lawrence was diagnosed with tuberculosis he couldn’t return, however much he dismissed his illness as bronchial troubles, malaria, chagrin.

Luhan was among at least 20 of Lawrence’s acquaintances who wrote books about him. It’s one of the more honest accounts and has provided inspiration for Rachel Cusk’s new novel, Second Place, and a key source for Wilson’s new biography. There have been several recent biographies of Lawrence, including the magisterial, day-by-day three-volume Cambridge one. Wilson, in a recent talk at the London Review Bookshop, dismissed all of them as totally wrong. So she’s battling her way into the fray, taking a pleasurably Lawrentian all-or-nothing attitude. She focuses on 10 years, from the publication of The Rainbow in 1915 to his official diagnosis with tuberculosis in 1925, although this doesn’t stop her writing about his childhood and early life.

This is a bold, fervent contribution to Lawrence studies, full of spirit and insight and enviably agile prose. It’s a fitting response to Lawrence’s embattledness, which arguably necessitates extreme investment and speculative volatility. It’s impossible to do him justice, so it’s better to go for a high-energy caper instead. One result of this is that Wilson propels herself into some loopy judgments. Her premise is that the major, hitherto unrecognized influence on Lawrence was Dante’s Divine Comedy. “Lawrence structured his life,” she writes, “around Dante’s great poem in the way that James Joyce shaped Ulysses around The Odyssey. This was his primal plan, the complex figure in the Persian carpet that Lawrence’s biographers because they have been looking from a flat perspective—have failed to see.” According to Wilson, his (medically driven) search for height in the houses he lived in was a Dantean quest for paradise.

It’s true that Lawrence’s lived experience was one of continual death and rebirth. He died with every disappointment and illness, was reborn with every new delight. We can see this in his response to World War I, where he goes on to say that he knew in the tomb that “I should have to rise again.” The identification of himself with Christ recurs repeatedly for Lawrence. Jesus gets almost no mention in Wilson’s biography, but Lawrence was obsessed with him from childhood onward. He frequently dismissed him, at stages rejecting Christianity because of his lack of belief. But he always identified with Jesus, and there’s something petty about his dislike of him that suggests he resented him as a kind of rival. Hence his obsession with resurrection: If Christ could do it, then why not Lawrence as well?

Sometimes he saw death and rebirth as a larger phenomenon, and then he thought in terms of apocalypse or cataclysm—a world destroyed and remade. He didn’t often talk about Dante (except in his cranky school textbook, Movements in European History), and when he did these were throwaway remarks of the kind all of his generation made. Although the idea that Dante is the figure in the carpet, structuring Lawrence’s life, seems absurd to me, we have to take it seriously here, because of the obsessiveness with which Wilson brings Dante into the picture as a kind of fellow conspirator with Lawrence. She structures her book around Dante’s hell (Cornwall in 1915), purgatory (Italy in 1919), and paradise (New Mexico in 1922) and juxtaposes Dante with Lawrence at all key moments.

She is moving on Lawrence’s death, high up on a hill in the French town of Vence, and astute on his afterlives. An astonishing number of people who had known him wrote memoirs after his death, and Wilson discusses Luhan’s and Aldous Huxley’s (he was there at Lawrence’s death, and Wilson calls his brief memoir—where Huxley praises his friend’s “unshakeable” loyalty to his “own self”—“the best account we have of what it was like to know Lawrence”). Lawrence’s ashes traveled as circuitously around the world as he did. It’s possible that Frieda’s lover Angelino Ravagli dumped them in Marseille and then took fake ashes to be buried in Taos, but either way there was a burial ceremony for him in Taos, presided over by Frieda, Mabel, and his friend Dorothy Brett, a trio Wilson compares to Dante’s “three such blessed women, / concerned for you within the court of heaven.” From this point, Lawrence’s reputation grew and grew, until the Chatterley trial brought him an apotheosis that was also in danger of calcifying him.

Perhaps because of the bold imaginative creativity of this vision, Wilson’s more minor judgments are often both original and spot on. She sees Lawrence as jealous to an extraordinary degree of babies and as turning against the poet Hilda Doolittle and against his own dog, Bibbles, as a result. She sees him as unusually curious about his own time as an infant. She sees him (I don’t agree here) as “a modernist only by mistiming.” These are provocations of the kind Lawrence himself might have made, party pieces inviting argument.

Wilson is great at deft character sketches (Mabel’s husband is “part warlock, part Buddha, part tour-guide and part playboy”) and great on gossip, especially about Frieda and Lawrence, who emerge as vibrant physical presences, he getting thinner and she fatter as they box their way through life. She gets carried away by gossip when she devotes over 100 pages to an analysis of Lawrence’s friendship with the trickster-cum-writer-cum-onetime-soldier Maurice Magnus. I disagree with Wilson that (another of her big judgments) the novels are not Lawrence’s major achievement, and I don’t think she makes a convincing alternative case for Lawrence’s brief biography of Magnus as his “best single piece of writing” (though he called it this himself, in what appears to have been a throwaway remark). Wilson gets as carried away by Magnus as she does by Dante, claiming he is not only the model for Lawrence’s “Mosquito” poem but for his brilliant “Snake,” missing all the particularity of that wonderful poem, which is a polemic against anthropomorphism.

What Wilson likes about the Magnus portrait is its spirit and energy, its willingness to open out from Magnus to make large judgments about the world, its gift for friendship. All this she shares. Her book is an enthralling and eccentric friend of a book (it’s appropriate that Lawrence’s friendships were as out of control as they were energizing), much more fun as a read than traditional biographies with more measured judgments. Compared with so many other versions of Lawrence, Wilson’s book offers rich ambivalence toward its subject, in place of a stark binary. It may be all to the good if neither Lawrence nor his biographers have the sense for health or the sanity that Leavis promised us.