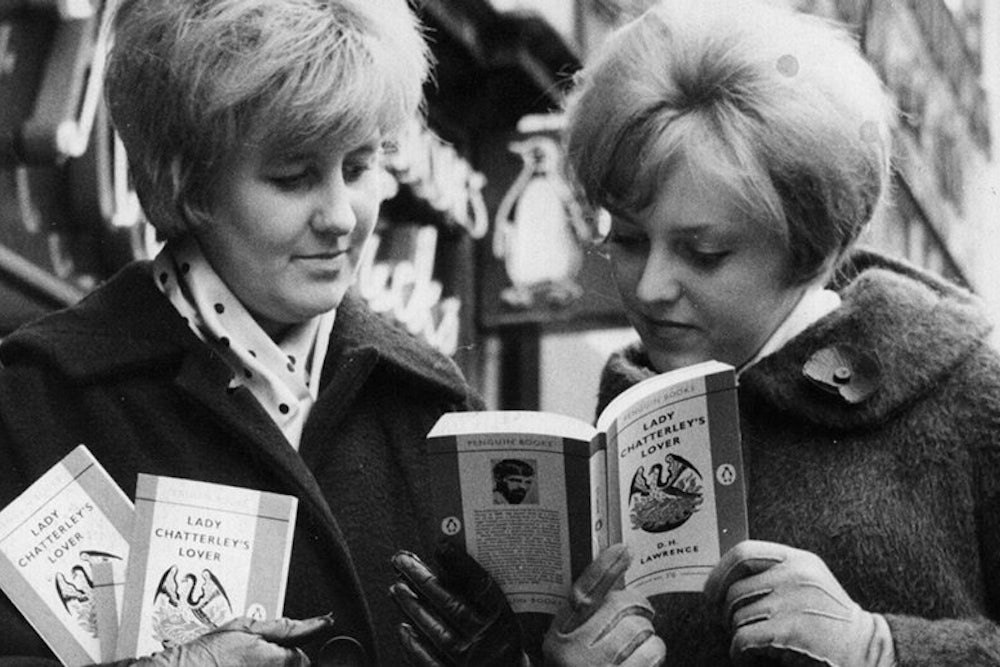

This fine novel of D. H. Lawrence’s has been privately printed in Florence, and it is difficult and expensive to buy. This is a pity, because it is probably one of Lawrence’s best books. About the erotic and unconventional aspects of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which have made it impossible for the book to be circulated except in this subterranean fashion, I shall have something to say in a moment. But Lady Chatterley’s Lover is far more than the story of a love affair: it is a parable of post-war England.

Lady Chatterley is the daughter of a Scotch R. A., a robust and intelligent girl, who has married an English landowner from the Midlands coal-mining country. Sir Clifford is crippled in the War, and returns to his family estate, amid the decay and unemployment of the industrial towns. At first, he occupies himself with literature, mixes with the London literary people, and publishes short stories, “clever, rather spiteful, and yet, in some mysterious way, meaningless”; then later, he applies himself feverishly to an attempt to retrieve his coal mines by the application of modern methods: “once you started a sort of research in the field of coal-mining, a study of methods and means, a study of by-products and the chemical possibilities of coal, it was astounding the ingenuity and the almost uncanny cleverness of the modem technical mind, as if really the devil himself had lent a fiend’s wits to the technical scientists of industry. It was far more interesting than art, than literature, poor emotional half-witted stuff, was this technical science of industry.”

But Sir Clifford, as a result of his semi-paralytic condition is in the same unhappy situation as the hero of The Sun Also Rises; and Lady Chatterley, in the meantime, has been carrying on a love affair with the gamekeeper—himself a child of the collieries, but an educated man, who has risen to a lieutenancy during the War, and then, through disillusion and inertia, relapsed into his former status. There has been an understanding between Sir Clifford and his wife that, since he is unable to give her a child himself, he will accept an illegitimate child as his heir. But Connie has finally reached a point where she feels that she can no longer stand Sir Clifford, with his invalidism, his arid intelligence and his obstinate class consciousness: she has fallen in love with the gamekeeper; and when she finally discovers that she is going to have a child she leaves her husband and demands a divorce. We are left with the prospect of the lady and the gamekeeper going away to Canada together.

Now Lawrence’s treatment of this subject is not without its aspects of melodrama. It is not entirely free from his bad habit of nagging and jeering at the characters whom he doesn’t like. Poor Sir Clifford, after all, for example, no matter how disagreeable he may have become, was a man in a most unfortunate situation, for which he was in no way to blame. And, on the other hand, Mellors, the gamekeeper, has his moments of romantic bathos. Yet the characters have a certain heroic dignity, a certain symbolical importance, which enable them to carry off all this. Lawrence’s theme is a high one: the self-affirmation and triumph of life in the teeth of all the destructive and sterilizing forces—industrialism, physical depletion, dissipation, careerism and cynicism—of modern England; and in general, he has given a noble account of it. The drama which he has set in movement, against the double background of the collieries and the English forests, possesses both solid reality and poetic grandeur. It is the most inspiriting book I have seen which has come out of England for a long time; and—in spite of Lawrence’s occasional repetitiousness and sometimes overdone slapdash tone—one of the best written. D. H. Lawrence is indestructible: censored, exiled, snubbed, he still has more life in him than almost anybody else. And this one of his books which has been published under the most unpromising conditions and which he must have written with full knowledge of its fate—which can, indeed, hardly be said to have seen the light at all—is one of his most vigorous and brilliant.

Lawrence has adopted the policy, in this novel, of throwing over altogether our Anglo-Saxon literary conventions, and, in his descriptions of sexual experience, of calling things by their right names. The effect of this, on the whole, is happy. I will not say that the unlimited freedom in this regard which Lawrence now for the first time enjoys does not occasionally go to his head: the poetic sincerity of the gamekeeper does not quite always save his amorous rhapsodies over certain plain old English terms from being funny at the wrong time; and one finds it a little difficult to share the author’s exaltation over a scene in which the lovers decorate one another with forget-me-nots in places where flowers are seldom worn. But on the other hand, he has greatly benefited by being able, in dealing with these matters, to do without symbols and circumlocutions; it tends to relieve him of the apocalyptic grandiloquence to which he has too often been addicted in his love scenes—it keeps these scenes recognizably human. I believe, in fact, that in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence has written the best descriptions of sexual experience which have yet been done in English. It is certainly not true, as is sometimes asserted, that erotic sensations cannot or ought not to be written about. D. H. Lawrence has demonstrated here how interesting and how varied they are, and how important to the comprehension of any emotional situation where they are involved.

The truth is simply, of course, that in English we have had, since the eighteenth century, no technique—no vocabulary even—for dealing with such subjects. The French have been writing directly about sex, in works of the highest literary dignity, ever since they discarded the proprieties of Louis XIV. They have developed a classical vocabulary for the purpose. And they have even been printing for a long time, in their novels, the coarse colloquial language of the smoking-room and the streets. James Joyce and D. H. Lawrence are the first English-writing writers of our own time to print this language in English; and the effect, in the case of Ulysses at least, has been shocking to English readers to an extent which must seem very strange to a French literary generation who read Zola, Octave Mirbeau and Huysmans in their youth. But, beyond the question of this coarseness in dialogue, we have, as I have intimated, a special problem in dealing with sexual matters in English. For we have not the literary vocabulary of the French. We have only the coarse colloquial words, on the one hand, and, on the other, the kind of scientific words appropriate to biological and medical books and neither kind goes particularly well in a love scene which is to maintain any illusion of glamor or romance.

Lawrence has here tried to solve this problem, and he has really been extraordinarily successful. He has, in general, handled his vocabulary well. And his courageous experiment, in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, should make it easier for the English writers of the future to deal more searchingly and plainly, as they are certainly destined to do, with the phenomena of sexual experience. He has evidently made the experiment at some sacrifice. I do not suppose that he has printed many copies of the original edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover or that he has made much money by selling them; and he has no literary rights over the edition which has been pirated and sold in America. This must be counted to Lawrence for righteousness. There can be no advance made in this direction without somebody’s taking serious losses. And since Ulysses, no English-writing novelist of first-rate merit has volunteered to do so.