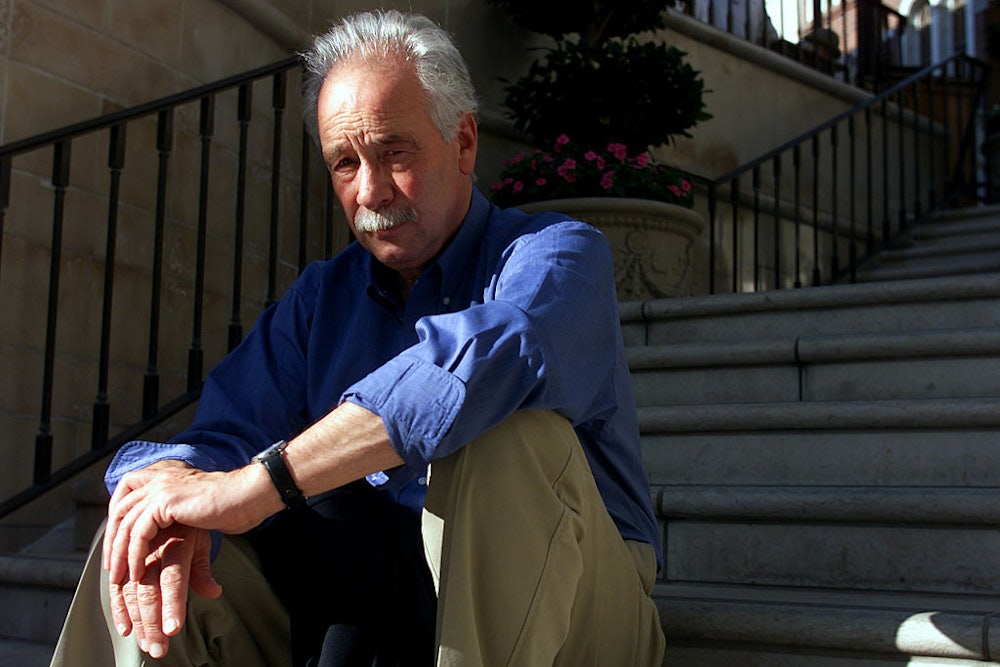

W.G. Sebald’s premature death from a heart attack, in December 2001, at 57—months after the publication of his novel Austerlitz propelled him to the height of his literary fame—has left his readers wanting more, and ever since, his publishers have increasingly delved deeper into his oeuvre for posthumous releases. Six full-length books have already appeared in English since his death, and now, 23 years after his death, we have the seventh—and perhaps last: Silent Catastrophes: Essays.

At first blush, the book risks feeling off-putting to the casual reader: Academic in tone, it focuses on a literary tradition often overlooked in America, featuring many writers who are largely unknown in English-speaking countries. But its focus on Austria—a crumbling empire that slowly but willingly descended into fascism as a means of trying to capture its former glory—means that Silent Catastrophes, unfortunately, is arriving at an apposite time. And the reader willing to wade through the academic style will soon find not only Sebald’s trademark concerns emerging but unexpected reflections on how we might navigate the end of empire and the rise of authoritarianism.

Through his reading of the writers who influenced him, these early writings make plain the ethical principle that guided Sebald’s great works: Melancholy, far from being defeatist, is itself a kind of political resistance, a way of pushing back against the machinations of fascism by preserving the past against erasure.

The biggest initial stumbling block to entering Silent Catastrophes is its style: Written by someone who was then a mostly unknown academic in the 1980s, it bears many of the hallmarks of a style not meant for casual engagement. There’s a frustrating lack of concession to the reader—it is presumed, for example, that you already know the writers he’s discussing—when, at best, only a handful (Thomas Bernhard, Franz Kafka, Peter Handke, Elias Canetti, and Arthur Schnitzler, whose Traumnovelle was adapted by Stanley Kubrick into Eyes Wide Shut) will be familiar to most nonspecialist English readers. The book is a compilation of two separate books of criticism—The Description of Misfortune (1985) and Strange Homeland (1991)—and reads as if you’re already up to date on the critical scholarship surrounding these writers, and at times it can feel as though one has wandered into a university panel entirely intended for other Austrian literature experts.

Rather than approach Silent Catastrophes as a series of scholarly essays, I found it more rewarding to read the book as a group portrait of a country and an empire in crisis, its writers both narrating the Fall while trying, in various ways and with various levels of success, to cling to some kind of meaning. I began to be less interested in the finer points of these writers, and more in understanding what the decay of Austria—refracted through its writers—has to tell us about today.

Sebald was born in rural Germany in 1944 but spent most of his adult life in Norwich, England, and he wrote these books as an immigrant in Thatcher’s Britain; it’s hard not to feel echoes of those disastrous years in the background of the book. As Jo Catling, editor and longtime Sebald scholar, lays out in her introduction, the essays in Silent Catastrophes trace the output of writers for whom Austria as a homeland became unheimlich: “not just ‘unhomely’ but both hostile and uncanny, strange in both senses.” For someone who may be feeling, in 2025, that their own homeland has become hostile and uncanny, there’s much here to help make sense of that feeling of eeriness, and a repeated attempt to chart some kind of path forward.

One easy way in is by focusing on those works that are already well known in America, including Franz Kafka’s The Castle and Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power, both of which Sebald discusses here at length. In both works, one written well before the Third Reich and one written in its wake, Sebald traces similar threads of how authoritarian power works: Born of a hatred of chaos and disorder, authoritarian power tries to exert violence over the land in its quest to enforce a sterile order. As he notes in his gloss of Canetti’s work, “Longing for total order has no need of life.” In fact, such a longing for order “is a murderous one. The Reich as a desert, and the dwelling place as a mausoleum in which the creator of order can rest for eternity, in a pose of his own choosing and in absolute safety—these are, as it turns out, the ultimate models to which the paranoid imagination aspires.” Pathological in its hatred of difference, strangeness, and messiness, such violence valorizes Egyptian pyramids and mausoleums, bloodless Roman columns, and the antiseptic concrete megastructures that Albert Speer conjured for his Führer.

Such power, as Sebald identifies in Kafka’s The Castle, is “anything but creative; it is completely sterile and its sole aim seems pointless self-perpetuation.” The despots in Kafka’s works, who endlessly bleed life from the oppressed, fundamentally have no stated rationale for committing such violence, beyond their own vampiric need to feed continually on the living. Kafka, Sebald notes, recognized fundamentally that power is “parasitic rather than powerful.” We can, in other words, stop asking what billionaires want, since by now they don’t want anything but power itself; for all of their actions and violence, they have paradoxically lost all agency, incapable of doing other than simply existing for the sole purpose of accumulating more.

But it is no longer enough simply to recognize how authoritarians work, and it would be one thing if Silent Catastrophes was merely diagnostic. What makes Sebald fascinating even decades after his death is the way he marks out possible lines of resistance—not in the traditional sense of protest, witness, and activism (all of which, it goes without saying, remain vital and necessary) but through other means altogether.

One of the crucial observations that runs through all of his work, and is explicitly discussed here, is how fascism alienates us from the natural world—messy and unordered—and that, in the authoritarian mindset, the “redemption” of nature “can only be effected by the use of violence,” since only through violence “does chaos become order; and this transposition legitimizes the use of violence as a quasi-divine act of creation.” (Donald Trump’s order to flood Northern California, a colossal waste of water that accomplished nothing, is only the latest iteration of this. Estranged from nature and disdainful of it, Trump sees it as nothing but a reflection of his own power: He wants to see water flooding from dams because it reflects back to him his own ability to disfigure the landscape that terrifies and confounds him.)

Our attention to the natural world around us, then, must encompass not just attention to climate change and our need to mitigate it but also a renewed awe of nature that sees it as chaotic and unformed, complicated beyond our reach. Attempting to engage the natural world, in whatever form, is more than just escapism; it is an attempt—if not to reconnect with nature—to at least document the rift that has erupted between us and it, a rift that grows steadily each day.

Our alienation from this natural world, accelerated and exacerbated by authoritarianism and the catastrophes of the modern age, for Sebald, takes the form of a kind of melancholy, a recurrent theme in all his work. But this melancholy need not be understood as some sort of decadent withdrawal or fatalism. As Sebald puts it in his discussion of Hermann Broch, “The logical function of tautology, in the field of aesthetics as in that of genetics or machine theory, is that it contains no information whatsoever; its counterpart, on an ethical level, is defeatism.” Rather than viewing melancholy as an abdication and defeat, or as just another synonym for clinical depression, Sebald is searching instead for a politics of melancholy—a means of turning this response to an all-pervasive calamity into a form of activism itself.

What does this mean in practice? For one, it involves a renewed call for teaching, which, Sebald argues, has always been so vital (“in contrast to Imperial Germany”) in the Austrian literary tradition. We have, perhaps, become over-accustomed to thinking of learning in terms of finite destinations: acquiring a degree, mastering specific skills, etc. As knowledge now comes increasingly under attack, we may need to build alternate networks of teaching and learning—outside of universities and credentials; diffused networks of teachers and learners that can be far more resilient and proactive.

As importantly, in highlighting these Austrian novelists, Sebald here is calling for a kind of art that resists the desire to be complete, to be perfect, to be ideal—for in this lies, he suggests, a similar impulse to fascism. “The invariability of art is an indication that it is its own closed system, which, like that of power, projects the fear of its own entropy on to imagined affirmative or destructive endings,” he remarks, adding that “already in the great symphonies one hears, in the final notes, the desire for destruction.”

It is in this impulse that the odd incompleteness of Sebald’s own great works come into relief: the way his final novel, Austerlitz, ends by more or less just trailing off and the way his earlier works are formed through collage and assemblage in lieu of a unified and coherent design. It also helps makes sense of his trademark usage of photographs and other images that break up and interrupt his text, which do so not as a form of illustration but as a form of cacophony. As opposed to “great art,” which is “always oriented towards eternal values,” we will continue to need more of “the work of the bricoleur, comprising remains and debris,” which “already bears within itself the destruction to come.”

Most crucial is Sebald’s attempt, laid out in the introduction to The Description of Misfortune, to offer another way of thinking of melancholy—not as depression but as praxis. “Melancholy, the contemplation of disaster in progress,” he writes, “has, however, nothing in common with a desire for death. It is a form of resistance.” Melancholy, for Sebald, is a kind of preserving force, a means of keeping alive the past—broken and in ruins, perhaps, but still in the forefront of consciousness. “On the level of art, in particular, its function is anything but reactive or reactionary,” because in keeping alive the possibilities inherent in the past, one preserves a hope for a future.

It may be that such a future is out of reach to us at the moment, but the melancholic clings fast to this anyway, like an archivist who knows that their knowledge and resources must be ready to be called upon at any given moment. “When, with a fixed stare, Melancholy considers once more how things could have come to this, it becomes clear that the mechanics of hopelessness are identical to those which drive our knowledge and insight. The description of misfortune contains within it the possibility of its overcoming.” For Freud, mourning was normal, a healthy process of working through loss, whereas melancholy was pathological, an inability to move on—Sebald inverts this entirely, suggesting that not only is melancholy not pathological, but it is precisely in the refusal to move on that political resistance might be found.

So much of Sebald’s work is rooted in the awareness that though memory and history are mercurial, often contradictory, and impossible to fix permanently, it is nonetheless vital to document and preserve it all, even the contradictions and confusions. For it is the job of the artist—melancholic though they may be—to sift among these contradictory pasts in search of possible futures that may yet be open to us.