This article originally appeared in The New Republic on June 11, 1990. Anne Hollander, a historian of art and style, died today. She was 83.

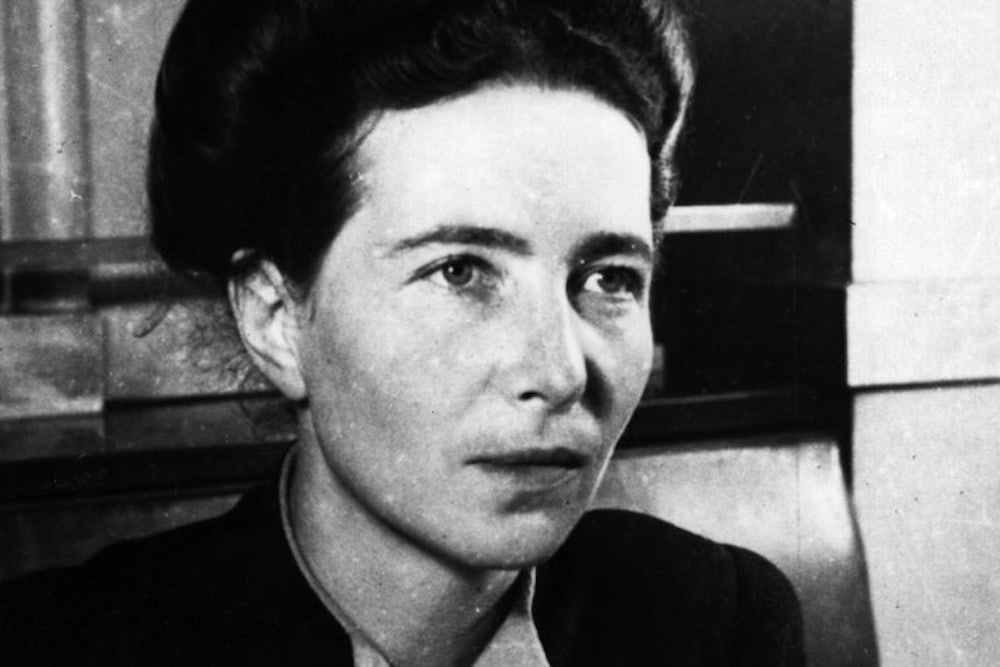

Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography

By Deirdre Bair (Summit Books, 718 pp., $24.95)

In the introduction to this massive book, Deirdre Bair says that her aim is to help future societies assess the real contribution of Simone de Beauvoir, determine why she matters. Beauvoir's personal fame still rests on her connection with Jean-Paul Sartre, although her international fame as a writer is based almost wholly on her prophetic work, The Second Sex, which was published in 1949, well before the current phase of feminism began. Besides that, she was the author of seven novels, a play, two books of philosophy, four volumes of memoirs, and about five other volumes of serious essays, apart from numerous introductions to the works of others, and many articles for periodicals. Her own view of the way she mattered was entirely as a writer, not as a lady-friend or as a feminist. She laid great stress on this, and disliked being remembered only as the author of a feminist document—the book, she said, that "anyone could have written."

Significantly enough, Bair does not publish a list of Beauvoir's works anywhere in this big volume. She claims to be disappointed by the prevailing emphasis on Beauvoir's life, compared with the attention paid to Sartre's writing; and yet she has made clear, in the farm and the nature of her biographical study, where she really stands. Although Bair scrupulously describes every writing project that her subject undertook, she shows that in the case of Beauvoir, when all is really said and done, the life was the work. In fact, apart from the importance of The Second Sex to feminism, her other writings cannot compare to the great works of literature that lead vital lives apart from their authors'. Beauvoir's philosophical works have not endured, and her novels, using the same material as her memoirs, are ultimately unimaginative, limited by their confinement to her own milieu and her own kind of feminine philosophical perspective. Like the memoirs, they have mainly historical value. This book supports the reasonable view that despite her pride in her metier, Beauvoir's contribution to the future will not be as a creator, but as an example.

She is, indeed, a great example. Perhaps only the future will properly understand how great, since, as Bair points out, many of her youthful admirers even in France have no conception of the way of life into which she was born, or of the kind of social and intellectual training she had, and therefore no sense of the heroism in the life she undertook. It is now both respectable and easy—and perhaps normal—for a middle-class European woman to get an excellent education, become a writer, form friendships and amorous liaisons with other writers, edit a magazine, engage in politics, teach, travel, lecture, and never marry, keep house, or have children—to feel free to pursue what used to be thought of as a man's life. It is now considered comme il faut, moreover, to cast such a life in the secular and godless mold.

For Simone de Beauvoir, born into the haute bourgeoisie in 1908, such a course was initially unimaginable. She began not only chained to ancient European ideals of female domestic and familial duty, but constrained by the rigidly Catholic upbringing that her mother imposed on her and by the limited education then provided for French upper-middle-class girls. Before she could lead her famous life, she had to imagine it; and French precedents were conspicuously lacking. American and English girls were already socially much freer at the time, and ideas about their education were much more advanced in those enterprising Protestant countries.

But history was, in fact, on Beauvoir's side, and so was an acute family poverty, which precluded a dowry and an arranged marriage at the correct social level. Although French women did not get the vote until 1946, a freer social existence and a better higher education did become more available to French girls in time for young Beauvoir to profit from them. She did not have to run away from home to satisfy her rising intellectual ambitions, or to avoid an odious proposed spouse. The family did not try to keep her stitching by the impoverished fireside throughout a genteel spinsterhood, but urged her to train to be a teacher and earn her keep. Her religious faith might just have to be sacrificed; they were proud of her prodigious distinction as a student, and she was still a credit to the family, even if unmarriageable on the right terms.

But she was pretty, too, and loved admiration; and her eventual heroic rebellion was manifested in the realm of sex. A true bluestocking was nothing new, but a female intellectual life was traditionally supposed to be carried on in a state of celibacy, modeled rather on the example of the great female saints and brilliant abbesses of the Middle Ages, who corresponded with popes, kings, and sages, arguing theology and swaying policy from the cloister. Seriously learned and thoughtful girls were supposed to avoid men, or else to be masculine themselves, to leave not only marriage, children, and housekeeping but the whole feminine erotic life to their sillier and more worldly sisters. Female artists and poets were known to engage in free sexual expression; female philosophers, never.

Beauvoir's relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre was a triumph of the impossible, a liaison preserved in a precarious, constantly readjusted balance. Bair shows Beauvoir maintaining the balance more or less single-handedly, protecting their autonomy but at the same time staying conventionally feminine in relation to him. This did not mean conventionally female, as a procreative wife and guardian of his hearth, or quasi-masculine, as a like-minded friend and comrade-in-arms. It meant imaginatively feminine, as a mistress and an intimate. She would be a sort of co-conspirator, someone unaccountable, wondrous, exigent, exciting, necessary. But since this amorous project was undertaken by two intellectuals, the mistress also had to be a colleague, not a pure engine of primitive temperament and erotic pleasure, but an equally well-equipped intellectual contender who would provide constant mental excitement while never really threatening him as a thinker.

Meanwhile the freedom that Sartre wanted was not just abstract but specifically sexual, and he reserved the right to collect other women with her knowledge and approval, leaving her the same freedom, just as if she were a male friend with the same leanings. How to work all this out? There were no models for this style of joint life, not in French intellectual history, domestic history, or anywhere. No wonder Beauvoir had to write about it constantly, no wonder the two of them had to discuss themselves constantly, together and with others, in print and in letters. It had to be grasped while it was happening, talked and written into existence and brought under intellectual control, in what appears to have been a great absence of any unspoken intuition. She solved the problem of his other women by entering into semi-amorous relations with them herself, emphatically not as a rival male but as a fellow narcissist, continuing her feminine theme by playing sexual games with them tinder Sartre's voyeuristic eye.

During most of their long affair from 1929 until the 1970s, Beauvoir gave Sartre the priceless gift of her intensive editing, bringing to bear not just her formidable intelligence and understanding of his thought, but all her linguistic skill and taste on every bit of his writing. She made him stop sounding pedantic and musty, clarified his diction, kept him up to his own standard. At the same time, as her newly published letters show, she adored him, and unreservedly lavished the treasures of her heart on him—notably always addressing him in the letters as "vous," like a proper French bourgeoise addressing a beloved parent. She made it abundantly clear, and not just to him, that her intellect was at his service before she used it for herself, as a village bride's maidenhead was at her seigneur's disposal. In relation to him, her intellectual posture was going to be traditionally feminine, too.

And ultimately his life and work were better served than hers by her determination to keep her woman's place and yield nothing of her feminine right to have a thrilling lover to serve, adore, torment, and manage, rather than simply a reliable husband. She took great risks to do this, and her behavior seems very contradictory, her attitude often obscure; she was struggling to find a modern path for the intellectual woman to take, one that would command respect for the full use of heart, body, and brain together, and for the full play of moral sensibility in a woman's life. She would not be a Muse of Fire, a woman known only for her legendary effect on great men, like Alma Mahler, Misia Sert, Lou-Andreas Salomé, any more than she would be a wifely chattel. She would not choose another woman and be safe inside the homosexual fortress. And she could not be solitary, a priestess of worldly renunciation.

She invented the idea of intellectual union as an image of the sexual bond; but this meant arranging to be perpetually "had" by him in front of everyone, according to the old notions she had inherited of what the sexual bond was. Beauvoir's methods only point up how much things have changed in the way the sexes approach each other. Her example does not even properly stand at the beginning of the new order; she marks, rather, the end of the old.

Inevitably her independent intellectual image was tarnished. It wasn't harmed by her sexual liaison with Sartre, which caused such disapproval in the social world, but rather by her quasi-wifely insistence on his absolute importance in the universe, not just to her; and thus implicitly on her own importance only as an adjunct to his, despite her tireless writing. Her image as imaginative mistress was similarly damaged by her motherlike wish to stand between Sartre and the importunate world, monitoring his practical affairs, choosing what appearances he would or would not make, explaining him to others when he did not explain himself—all of this much to the noticeable irritation of spectators.

Thus she would deal with all the unpleasantness and take all the blame, being the villain so that he might go out to play unhindered and preserve his appealing flavor before the public. She was like the unworldly doctor's wife who collects the fees he fails to charge, or the charming wastrel's wife who staves off the creditors with shaming lies. In such cases, doctor and wastrel are always better company and seem wiser and nicer than madame; but madame's status as true wife preserves her honor in the performance of these thankless marital tasks. Beauvoir was the colleague and the lover, not the wife. She often made him seem unhappily married when he carefully was not, and made herself seem hypocritical, since she proclaimed herself his critic and equal, not his agent and keeper. But Bair believes that Beauvoir assumed this awkward position in Sartre's life with his express connivance, and that they both understood his need to have her do it, as much as her wish to do it, however it seemed to outsiders.

As a free-standing intellectual woman, she might more appealingly have chosen a clod or a sprite as a permanent male companion, someone providing Passion and Otherness in the masculine manner, who would have given emotional support and not gotten in the way of her personal glory in her chosen field. Many creative men and some creative women have certainly done this—but Beauvoir was not a self-sustaining artist. Or she could have joined up with a great physicist or a great cellist and kept her own enterprise to a separate standard in a separate world. By hitching her feminine intellectual's fate to the career of a prominent philosopher, she risked losing her independent identity as a thinker; and she did, in fact, lose it. She is often called one of the foremost intellectuals and literary figures of her day, a leader, but in those respects her name is never mentioned without Sartre's. She is perceived as a part of his intellectual group and not separately, the way Camus is. Sartre, of course, is easily thought of independently of her.

Her novels and her memoirs are all alternative expository versions of her life, and that meant her life with Sartre. Only Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, published in 1958, which deals very movingly with Beauvoir's childhood and youth before she met him, can claim independent importance as a memoir; and Bair says that it evoked almost as much response from French women as The Second Sex had done. But the others do not transcend the complex trap of her fell attachment, interesting and informative as they are. Her thinking, her political and editorial work, her philosophy, her fiction, her other love affairs were all contained by the larger connection with Sartre, which organized her life and produced the reasons, the enabling conditions, the necessary opposition, even when she was far from him.

Only with her inspired applications of his philosophy to her original study of women did Beauvoir find her separate universe and create a work that stands outside him, and finally outside herself. It is the only book in which she makes a large imaginative leap out of her own circumstances; that's why it's so extreme, so repetitious, so stumbling, so crude by comparison to some of her other productions. It is a great work because it is detachable enough to immortalize her. Everything else is stuck inside her personal myth, with no life of its own. The Second Sex for once has no single woman at the center, being or standing for her superior self: all women form the group she is trying to join, and on equal terms.

Unlike the feminist literature that followed it, The Second Sex is not a detailed program for the future; it only shows the need for one. It was the first discussion that minutely described the ways in which women have willingly placed themselves in the role of Object, sharing (often with profit) in masculine myths of the Other. Beauvoir articulated the process by which women, by agreeing to live in comfort inside the fantasies of men, put themselves in a permanently false position.

They help to create a world, she wrote, where men are forever feeling betrayed, not supported, by the true character and the quality of women, because when fantasy is governing perception, the truth appears as a blasphemy. Neutral facts about women are perceived by men, and by women themselves, not as welcome illuminations but as bad news, festering blemishes on the lovely structure that both sexes agree is woman's proper moral and physical shape. Men need the structure and try to force its preservation; but they also feel entitled to hate the rituals of fakery that women perform to maintain it, especially when they tail. Women in such a world feel chronically in the wrong, most acutely wrong in moments when the truth of the self betrays the fantasy, but obscurely wrong in essence for consenting to the fantasy in the first place. Woman as Object may be spared the burden of responsibility carried by primary Subjects only by suffering the dishonor of constant two-way self-betrayal. Much heavier burdens and worse sufferings then follow, as women are given and often meekly accept every form of raw deal in punishment tot representing falsity and moral weakness.

The sophistication of Beauvoir's account gave her book a lasting resonance, but her brisk solutions of 1949 were too simple for the way that history was going. In her book she expressed hope for women only in the abolition of marriage, which would naturally follow upon the abolition of capitalism; independent female work would create independent female self-awareness along with economic freedom, followed by universal respect for women's autonomy. But as the cold war progressed and the revolution of 1968 burst out and reverberated, she clearly saw that women were left unfree by the sort of political upheaval she thought would redeem them. Women were still making coffee, not policy. Although she continued to maintain that "a Feminist is a Leftist" and kept her own left-wing position, she also understood that after 1968 many radical women, finding themselves effectively sidelined by the revolution, needed a feminist movement that was independent of ordinary radical politics. It became clear that unless sexual politics acquired its own left and its own radicalization, the liberation of women could not be achieved by ordinary political means. The leadership of such a movement she gladly put in the hands of others. During the twenty years of later feminism that she lived through, she did not write a sequel.

She did, however, work hard for women. As feminism gradually took over much of Beauvoir's energy in the '70s, her attentions to Sartre diminished; the care of him and his ideas was shared with others. In Bair's account, Sartre seems glad that she had something to amuse her while he was busy with his book on Flaubert, who didn't appeal to her; or with the new philosophical ideas he pursued after The Critique of Dialectical Reason in 1960, which she deplored and rejected because they repudiated what he had achieved in 1943 in Being and Nothingness, and therefore betrayed the essential Sartre; or with the many left wing groups in which her own interest had begun to wane. But she still dropped everything to travel with him when he followed The Revolution all over the globe, and only incidentally acknowledged her own growing feminist fame in those same places. In all her interviews with Bair, she stuck to Sartre's preeminence as the original mind and saw herself mainly as the constant writer, the busy castor, rather as if writing were housekeeping, which it clearly was for her, an exercise in the mental cleaning up of untidy experience, a form of understanding and not a detached creative act.

So it was with Beauvoir's celebrated affair with Nelson Algren, and it finally drove him off. Their strong trans-Atlantic passion lasted a long time and gave both of them great satisfaction, before her rage to write about it ruined it forever. It also redressed the balance a bit between her and Sartre, whose many liaisons cumbered their life with heavy emotional furniture that constantly needed dusting and shifting, often by her novelistic method. Algren really loved Beauvoir and wanted her to move to America to be with him permanently; but she persisted in fitting him into her governing plan with Sarte, and she couldn't understand why he couldn't understand that. She also actually published one of his love letters, and still she did not know what made him so angry. She kept him as a friend and informant, however, with all her genius for preserving relationships, and she wore his ring until her death.

What Algren couldn't know, apart from the terms of her peculiar arrange mere with Sarte, was how much she was part of a wholly French literary and intellectual tradition, something only occasionally echoed in America and not transportable. I'll go and live in America she would not only have to give up her philosopher and her language, she would have to become a different person. Only in Paris (and in French) could she Jive in public as a full-time professional intellectual, interpreting political developments and literary movements, sifting and considering current events and historical moments according to abstract ideas, undertaking to apply a refined apparatus of educated thought and principle to everyday occurrences and register the results—and, very important, to conduct tiffs daily life of the mind not only in essays, plays, and novels, but in conversations, in cafes, in a crowd, in active politics, and in constant full view. It wouldn't have been the same in Chicago among the lowlife Algren liked.

The daily life of Beauvoir and Sarte in their great days in the late 1940s sounds like the prolongation into maturity of urban Student Life (before the days of multisex residence halls), when nobody has any money or a real apartment, some live with their parents, and people sleep in marginal furnished rooms. Lovers and friends and followers leave their cramped quarters to spend hours and hours in coffee shops, talking and talking, meeting and parting, grouping and regrouping, conniving and intriguing, writing and thinking in each other's company, and incidentally eating and drinking, when finances permit. No bourgeois domesticity whatsoever, but an unrooted state of perpetual adolescence. Beauvoir and Sartre moved from hotel to hotel, each in a different single room, or Sartre lived with his mother, and real life and work went on for years at a sequence of café tables, or occasionally on the barricades. Later in the 1950s and after, they did have apartments that were often uncomfortable and ill-equipped, although Beauvoir's last one was fairly grand, acquired on the proceeds of the Prix Goncourt.

She won the prize in 1954 for The Mandarins, an enormous novel about the problems of urban intellectuals in a post war world. She showed how the politics of thoughtful people, though originally founded on clear principles and high ideals, lose all hope of purity in the aftermath of a war tainted with collaboration and blackened by the Holocaust. Memory is haunted by deaths that occurred through the slimy betrayals of friends, not just at the clean hands of enemy troops, and all political thought is clogged by a troubling lust for reprisals. Meanwhile politics are swiftly polarizing, and the need for self-defining action is immediate. Beauvoir dramatized the conflict between the writer's own impulse (pictured as unworthy) to withdraw from the mess and write for posterity with a clear head, and the pressure on the writer to banish his fastidious detachment and join the fray to save his soul.

These problems are not confined to that particular moment in history, of course, and the novel generates real excitement. It also has constant fast dialogue, many changes of scene, a touch of violence, a thread of sentimentality, and some intermittent sex: it reads like a screenplay for an endless television series. Alternating with the intellectual dilemma is the personal struggle of the central female character; although the novel otherwise depends on an omniscient narrator, this main woman's part is rendered in the first person, so that we are left in no doubt about her liner brand of insight and honesty. Other women respond to pressure by vamping every man, selling out, going mad, or turning perversely self-destructive: our heroine may weep a lot, but she keeps her objective stance, her sexual dignity, and her ability to speak the truth. And most of all, you see, she really understands men. Beauvoir makes the character a psychiatrist, so that this version of herself even has a license for her superior knowledge of others, her self-control, her irritating tolerance. She also has a true love and real work, unlike the other women in the book, and a healthy sexual appetite. By using the first person to convey this paragon, Beauvoir makes the novel judiciously self-aggrandizing, and compromises her excellent perception of male points of view, to say nothing of other female ones.

American responses to the spectacle of Sartre and Beauvoir include a certain irritation at their sense of their own importance, their belief in themselves as the center of the thinking world. It could seem quite true in the Paris they inhabited, soundproofed as they were inside their coterie and able to hear only the immediate resonance of all their own remarks, even to each other. Behind their Parisian tableau at the Café de Flore stretched the long history of French intellectual life, back to the realm of the salons and the philosophes, the tradition of enlightened discussion and educated, dynamic exchange that continued in the later Parisian worlds of Balzac and George Sand, Baudelaire and Zola, all mounting barricades and sitting at cafe tables, too. Supporting it all was the general legacy of French culture to which Sartre and Beauvoir were conscious and honorable heirs, however modem their immediate concerns and however unconventional their personal association. They could justly feel themselves candidates for lasting importance, at least Parisian importance, and at least while they sat there.

Beauvoir's own importance as a writer is compromised by her careless prolixity, by the steady rush of unedited utterance that floods across the barriers between fiction, philosophy, and memoir. With all her crisp intelligence, she still piles up loose heaps of prose in an attempt to tell many truths at once, collapsing boundaries with great urgency but insufficient art. There is a conspicuous lack of poetic compression in her work. Her excessive, serious, confidential mode of writing gives an emotional cast to her whole career as a woman of letters, and it conveys the poignant conflicts that may hamper a modern woman's creative work. Beauvoir embodies a tension between detached creative thought and personal creative feeling that many women find hard to manage, now that they are trying to be honest female thinkers and not just to follow all the right male models. She is a great witness to female experience; but a lack of rigorous self-editing finally keeps her out of the writer's pantheon. She preferred to turn her editorial forces on Satire's efforts, to make sure that he got there instead.

Bair's book is packed with information, a monumental example of excellent organization and responsible apparatus. The sustained personal tone, established from the start by her description of six years of interviews with Beauvoir, gives an agreeable unifying texture to this long, detailed story. Bair is perpetually discovering this remarkable woman and explaining her to us, responding throughout to Beauvoir's behavior and feelings, both directly as they talked and indirectly, as Beauvoir presented herself in her writings and appeared through the eyes of other informants and writers.

The book is designed as a sort of corrective to the subtly cooked memoirs, an emendation partly elicited from Beauvoir herself, whom Bair reports as eager for the exercise. All the chapters and the man), notes, while describing biographical events quite impartially, are nevertheless punctuated with references to what Beauvoir said directly to Bair about the events in question, and how she seemed to feel about what she said. The overall effect is successful: you feel that you know the woman better than she knew herself, and you're glad to get past the rebarbative, humorless image she seemed deliberately to project.

The trouble is, you also feel you know Bair better than she might like. Without any overemphasis, Bait very properly writes this book as a feminist, and she makes us conscious that she is a woman dealing with another woman's career in the light of modern feminism—a sister, not just a detached biographer dealing with a writer's life. But there is another side to it all. In the process, Bair is unfortunately exposed as a writer who is herself not so profoundly devoted to language as her subject was. Her temporary intimacy with Beauvoir, combined with attentive and copious reading in French and English and an excellent sense of structure, simply cannot make up for what comes through as an unseemly level of linguistic carelessness, in a book about a fundamentally classical writer.

Solecisms are the more noticeable if repeated, and this is a long book. She uses "flaunt" for "flout" not once but four times, and "centered around" on nearly a dozen occasions. "Imprecation" is used twice incorrectly to mean "exhortation," and "equivocation" incorrectly to mean "ambivalence." Phrases such as "equally as important" (twice) and "they accepted to believe in it" are not acceptable, nor is the sentence, "I did not disavow her of this idea." She uses "mutual" to mean "common," "symposia" as a singular, and "cower" as a transitive verb. I promise to refrain from further examples, except to object to a vague desire to seem literary that produces the frequent use of "within," when "in" would be right.

Bair's display of a shaky extended vocabulary in English raises doubts about her relation to language altogether. Her ear for French may be less good than one would hope and her ear for French civilization may be somewhat questionable in consequence, although she covers her tracks very well. She leaves no glaring misconstructions or mistranslations, only a lingering mistrust; all those flaws in diction give an ill-educated impression. They suggest that despite her intelligence and level-headedness, and great skill in molding huge amounts of diverse material into readable paragraphs, this American writer cannot take the complete measure of her highly cultivated French subject.

Meanwhile there is ample reason to be grateful for this book. One of the best sections deals with the process by which The Second Sex found its American publisher and its English translator, a story of dreadful, semicomic transcultural misunderstanding, and of heroic labor. The lengthy and devoted undertaking of H.M. Parshley, the zoology professor who made the only English translation of the book and edited it for an American public, makes a tale in itself—one with an unhappy ending, since his name never got on the jacket, he was paid very little, and he literally died of the effort. He was a privileged white male scientist, not an oppressed woman; but it was his sustained belief in the value of The Second Sex that ensured its early fame among the English-speaking public.

Bair's detailed story of Beauvoir's and Sartre's activities during and after the war is very welcome, with its exact elucidation of the parts that they played in the Resistance and the Occupation, and in all their lengthy, sometimes dubious political involvements. Bair is extremely good at sorting out rumors and their sources, tracking down and synthesizing alternative statements and explanations to form a believable, coherent whole out of a great deal of confusion. With all her sympathy she does not spare or excuse her subject, and she therefore seems trustworthy about the unpalatable elements of Beauvoir's life and character, which Beauvoir herself glossed over in her self-examinations. These include her often embarrassing abrasive manners and occasional displays of cruelty, along with the lame behavior that seemed to verge on collaboration during the war. On the other hand, Bair is quick to scotch malign reports if she can prove them wrong, and the inexpert reader comes away with the comforting sense of having a true account.

Bair's book deftly rescues Beauvoir from herself, wrenching her right out of her heavy French frame. The reader can't help being affected by the author's rapt attention to this twentieth-century ancient monument; Bait's youthful amazement at Beauvoir's actual humanity is catching. Along with all the facts, she renders Beauvoir's vivid memory for fifty-year-old humiliations, her fits of anger and amusement, her brusqueness, her vagueness, her devotion to strong drink, and her tendency to self-deception, all with a sort of affectionate piety and wonder. And she makes us see her plainly and feel for her sharply, as she follows Beauvoir through her long, fierce, moving, and radically exemplary woman's life.