Sometime in 1988, the actor, musician, and painter John Lurie was busy designing the cover for Voice of Chunk, an album by his band, The Lounge Lizards, then slated for release in Germany. Lurie wanted to revise the original cover art, which foregrounded his face in profile, framed by a saxophone, and which annoyed him. His solution? An eel. That is: a photo of a live, or at least newly dead, eel, laid out in a straight line, bisecting the photograph.

Lurie went to the Fulton Fish Market in the Bronx, in hopes of procuring an eel. No such luck. Then to the docks, where fishing boats unloaded their fresh catches to wholesalers. No eels there. So he drove to Chinatown, where he found eels floating in a tank in a restaurant and proceeded to barter with a well-dressed man, who, as it turned out, was unflappable, refusing to sell Lurie an eel or even to make eye contact with his prospective and highly motivated buyer. Then, seemingly from out of nowhere, a little old lady tugged at Lurie’s sleeve and led him down an alley, into a shop stacked with aerated tanks, loaded with rare fish. After some business with a net, this tiny woman snagged an eel and sold it to Lurie for $200. He put it a bucket and drove back to his apartment, where the eel, which looked like it had died en route, seemed to snap back to life, attacking Lurie. Fighting for his life, he strangled the slippery fish, washed it off, framed it on a windowsill, and photographed it. And that, edited for brevity and clarity (believe it or not), is the story of the elongated eel stretched across the cover of Voice of Chunk, a 1988, self-released, avant-garde jazz album by a group you’ve probably never heard about.

The eel story constitutes a formidable block of the third episode of Painting With John, Lurie’s new and welcomely indescribable HBO series. The show is a spiritual sequel of sorts to Fishing With John, the cult TV series that saw Lurie idly angling alongside a rotating cast of deeply intense celebrity guests (Dennis Hopper, Jim Jarmusch, Willem Dafoe, etc.). Fishing With John remains a singularly odd piece of TV, driven by irreverent (and often irrelevant) narration and the uneasy chemistry between Lurie and his fishing buddies (his expedition with Hopper includes an extended, and highly competitive, ping-pong match at a Thai beachside resort). It premiered in 1991, well before premium cable had cemented itself as the dominant media form, back when HBO was still primarily known for broadcasting boxing and Tales From the Crypt episodes. Fishing With John took the humble, lazy, Saturday-afternoon fishing program and elevated it to performance art, without making a big fuss of it. It remains one of the few TV shows to be included in the Criterion Collection, that august distributor of “important classic and contemporary films,” alongside arthouse telenovelas by Ingmar Bergman and Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

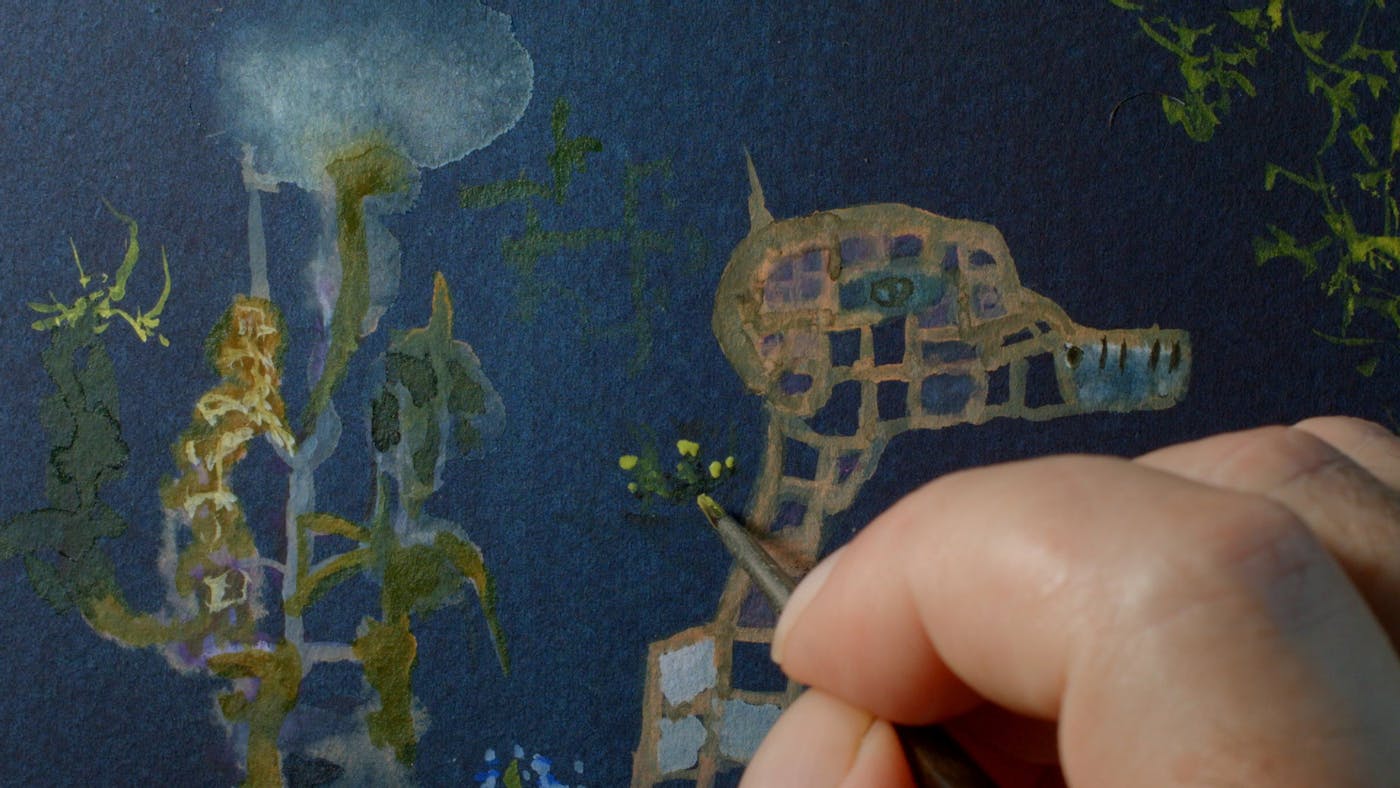

If Fishing With John was, in vaudeville terms, a two-hander, relying on the awkward interplay between Lurie and his guest, Painting With John is mostly a one-man show. Lurie has a face like one of those big Easter Island heads, craggy and severe, a piece of ancient geometry. And you spend a lot of time looking at it, as he stares down the barrel of his camera. His voice is gravelly enough to match his craggy visage. It, too, gets a workout. Shot on location on his densely leafy manse somewhere in the Caribbean, each episode captures Lurie bowed over a watercolor painting, vamping with jazzy, improvisational abandon on his life, his inspirations, or the time he was forced to strangle an eel in his kitchen. As the camera zooms deep into the inky, undulating blobs formed by his painterly daubs, these ambling discourses develop an almost hypnotic quality. They proceed without any discernible destination in mind, frequently disappearing down dead ends and blind alleys, interrupted by the storyteller catching sight of a beautiful-looking bird chirping somewhere in the distance. These stories, like the series itself, are utterly unlike anything that customarily qualifies as television.

Painting With John restores something of premium cable’s initial promise. It is singular, and strange, and obviously the work of a distinct perspective and personality. In this way, it recalls another recent HBO sleeper hit, by another guy called John.

How to With John Wilson, like Painting With John, is a playful riff on the instructional video. It’s equally indebted to chipper YouTubers with their “Hey, guys!” intros and the experimental New York City confessional films of Jim McBride and Jonas Mekas. Each episode sees host-cinematographer-narrator John Wilson offering advice on a given topic, like “How to Split the Check” or “How to Improve Your Memory.” Using a form of montage editing that seems practically free-associative—but is, I suspect, actually extremely deliberate—Wilson’s quests veer off on wild narrative tangents. Before you know it, an episode on small talk has led him to an MTV party at a Mexican all-inclusive. The intensely moving “How to Cook the Perfect Risotto” finds Wilson at a ski resort, attempting to pop a balloon by exposing it to high altitudes, before settling into a meditation on isolation and the current Covid-19 predicament.

Both shows are rooted in a deep intimacy, a rare quality in an era of social distancing. Like Wilson, Lurie doesn’t just invite you into his neurotic headspace. He traps you there. It proves a bit frustrating, even alienating. Still, such feelings are themselves refreshing, distinguishing these shows from the usual raft of streaming content that viewers are encouraged to consume in marathon “binges.” I found myself only able to tolerate one or two episode of How To at a time and savoring Painting With John as a bedtime digestif, an extended moment of zen. (This shift to a quieter, more meditative form of television seems to be trending: Superstreamers Netflix and HBO Max both recently launched series adapted, improbably, from popular meditation apps.)

During a 1996 appearance on David Letterman, comedian Jonathan Katz was asked about the undulating “Squigglevision” style used to animate his cult Comedy Central series Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist. In trademark deadpan, Katz explained: “The motion of the characters really represents the emotional turmoil that the characters are in.… And it’s cheap.” This rationale was front of mind watching How To and Painting With John. The intimacy and the economy are completely entwined. They are reprieves from, if not intentional ripostes to, television’s new blockbuster standards. Their hosts may fumble and drop the camera, flub a line-reading, or repeatedly crash an aerial drone (Lurie admits to demolishing seven in his bungled attempts to shoot the show’s airy, glossy opening sequence). This feels suited to the conditions of a pandemic, imagining a way of making TV without huge crews, lavish post-production budgets, or even a real cast. These shows could just as easily live on YouTube or at the bottom of a box of VHS tapes you find at a yard sale. Even premiering as premium cable “events,” they possess a ruddy, half-forgotten peculiarity.

And there’s something else these shows seem to restore: television’s prospects as a real-deal art form. Calling something “art” can grate. It’s a little instrumental. It’s as if we’re only afforded permission to take something seriously, or consider it at all, if it meets an agreed-upon standard of artfulness. If it’s art, then it’s OK to like it. We’re supposed to feel guilty about liking Saved by the Bell reruns or Vanderpump Rules, precisely because there’s no way we’d ever confuse them with actual art. Labeling something “art” becomes a plea to take it seriously. Was it always like this? Were people living in Paris in the 1930s badgering their friends: “Oh you gotta check out this new Manet exhibit! It’s art!” I don’t know. I’m also not sure how calling Painting With John or How to With John Wilson “art” changes how a prospective viewer might consider them. I’m not even positive if I, personally, think these TV shows are works of art, whatever that means.

Still I’m confident that both these programs suggest the possibility of originality and deep intelligence in a medium that’s as commercially compromised as any other. In the best way possible, they’re totally pointless. In one episode of Painting With John, Lurie rolls a discarded tire down a hill, for no reason save the sheer pleasure of doing so. That scene is these shows in a nutshell. They’re aimed at nothing in particular beyond the exploration of ideas and intuitions, lulling you in, letting you vibrate on their rhythms. And they do so while playing not to their medium’s newfound seriousness and critical respectability, but against them.

As John Wilson notes, ruminating on an art exhibit dedicated to common, everyday industrial scaffolding, “I guess it doesn’t take much to transform such a common object into something extraordinary.” No, not much. And sometimes, less is much, much more.