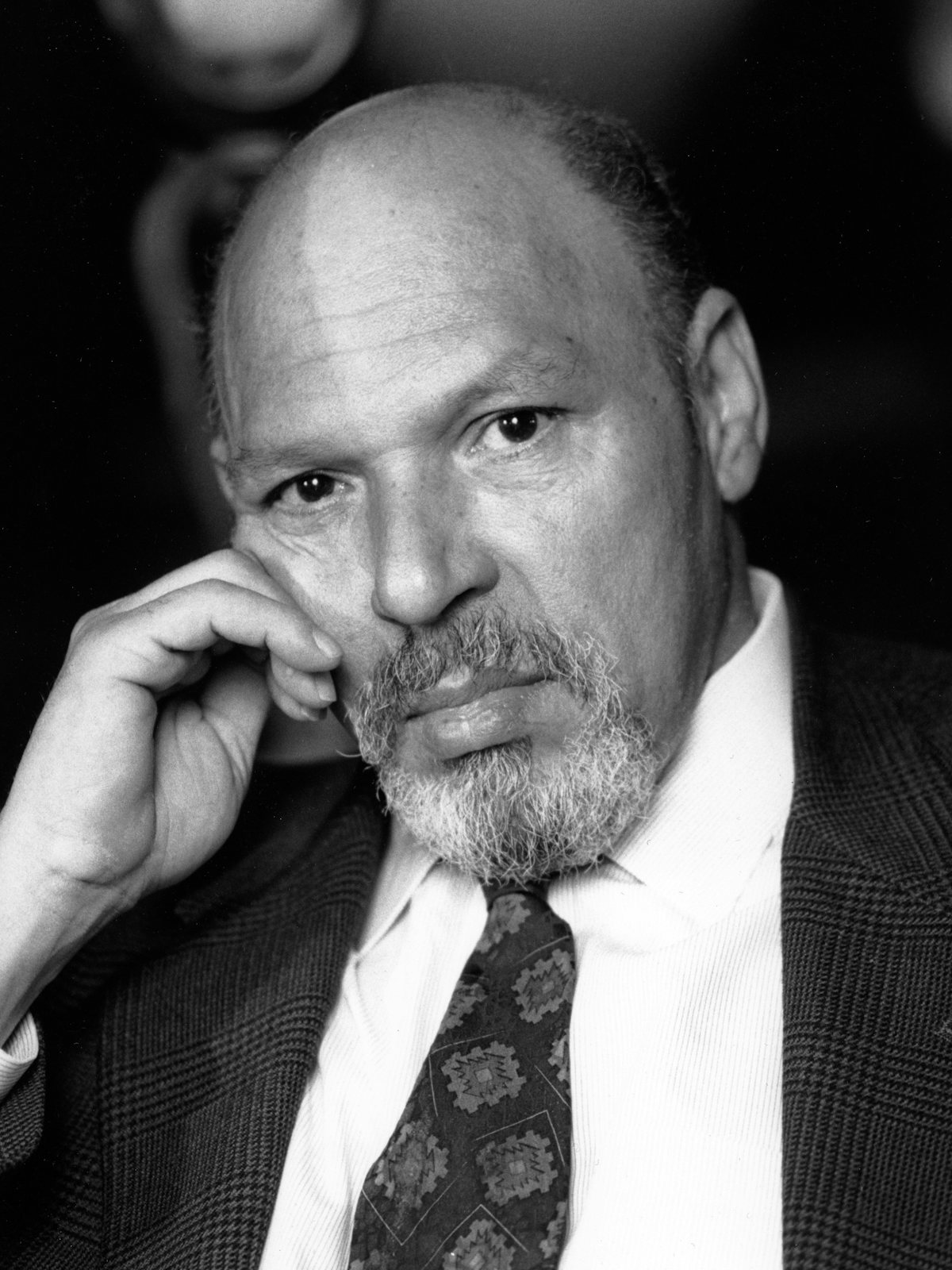

August Wilson had a magnificent ear. His supreme gift as a playwright was for transforming African American vernacular into crystalline poetry onstage. His sense for language was also evident in how he chose to be known. Growing up in the largely Black, poor, and working-class Hill District of Pittsburgh, dreaming of the sort of literary glory enjoyed by his idols Richard Wright and Langston Hughes, the young man must have known that “Frederick Kittel Jr., Great Black Writer” somehow didn’t have the right ring to it. At the age of 20, he rejected being the namesake of his father, a white, German-born, alcoholic baker who was, the playwright would later recall, “a sporadic presence” in his life. “August” was originally his middle name. “Wilson” was the maiden name of his Black mother, Daisy. Put the two together, and you had a moniker exuding steadfast wisdom, a name with gravitas, a name commensurate with its owner’s audacious ambition.

In the early 1980s, August Wilson embarked on a theatrical decathlon of his own design, aiming to write 10 plays, each set in a different decade of the twentieth century, that would reflect African American culture “in all its richness and fullness.” The time frames of the plays did not unfold chronologically. Take, for example, three of Wilson’s best: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (set in 1927) was followed by Fences (set in 1957), which was followed by Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (set in 1911). Collectively, the 10 plays would be called both the Pittsburgh Cycle and, perhaps more aptly since one of the works is set in Chicago, the American Century Cycle. Between 1982 and 2005, Wilson worked steadily, averaging a play every two and a half years. The tenth and final play in the Cycle, Radio Golf, premiered five days before his sixtieth birthday. Mission accomplished, he died of liver cancer six months later.

The plays are remarkable in both the depth of their historical exploration and their breadth of tone. The most emotionally wrenching are the two that take place earliest in the century. For many of the characters in Gem of the Ocean (set in 1904) and Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, slavery is a living memory and the Middle Passage an ancestral trauma that returns in nightmarish visions that, horrific as they are, can lead to a redemptive “washing of the soul.” Meanwhile, two of the plays set later in time border on satire in their caustic wit. In both Two Trains Running (set in 1969) and Radio Golf (set in 1997), Black folks strive to make it in America’s capitalist game only to find that, for them, the rules are subject to constant color-coded changes.

Wilson was showered with accolades, among them two Pulitzer Prizes, a Tony, two Drama Desk, and six New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards. Even in his lifetime, the literary establishment was carving out his space on the Mount Rushmore of American Dramatists, alongside the monumental figures of Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller. Toni Morrison, in her foreword to the published text of The Piano Lesson (set in the 1930s), praised the epic grandeur of Wilson’s oeuvre and his genius for evoking the beauty of Black American speech—even while acknowledging “respectful reservations” that some critics had expressed about some of his plays: “their length (too much), a plethora of deus ex machina devices (ghosts; characters who live for centuries; sudden, senseless death) and sermonizing instead of storytelling.”

It is rarely noted today, but, in the last decade of his life, Wilson came to be seen—in the eyes of America’s theater establishment—as something a bit more fierce and troubling than a benign Broadway griot conjuring the history of his people onstage. In June 1996, at the peak of his fame and influence, Wilson gave a speech titled “The Ground On Which I Stand” that shocked and appalled prominent arbiters of the dramatic arts in America. Proudly proclaiming himself a “race man,” Wilson offered a blistering critique of “cultural imperialism” in the theater world and made a bold, blunt call for Black self-determination in the arts. Nine years later, in Radio Golf, Wilson would ridicule ambitious African Americans of the Clinton era who surrendered their principles for “a seat at the table” with high-status whites. With this speech, Wilson, who had been welcomed and fêted more enthusiastically than any other Black playwright, effectively knocked the table over. In his foreword to the text of Jitney (set in 1977), the always-iconoclastic Ishmael Reed wrote that Wilson wanted to distance himself “from the neo-cons and neo-liberals who had claimed him as a member of their ranks.” As a character in an August Wilson play might put it: Them white folks thought he was they boy. But he wasn’t studying them.

Wilson’s insistence that African Americans “have control over our own culture and its products” explains why it has taken several decades for any of his plays to make the journey from stage to screen. A compelling film version of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom premiered on Netflix in December, arriving four years after a superb adaptation of Fences. Both films showcase illustrious Black talent in front of and behind the cameras. A generation ago, Wilson’s demand for Black artistic independence led some to call him a “separatist”; his stance was considered at best unrealistic. Today, he seems more like a visionary.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I sensed that a lot of older white theatergoers I spoke with felt a bit virtuous about attending August Wilson plays. They would say, “I loved The Piano Lesson” with the same sort of self-regard as the dad in Get Out when he declares he would vote for Obama a third time if he could. Seeing an August Wilson play wasn’t just a great night out at the theater—it was an edifying anthropological excursion.

“Don’t never let nobody tell you there ain’t no good white people,” the former slave Solly says in Gem of the Ocean. But good white people are hard to find anywhere in the Century Cycle. In a cumulative dramatis personae numbering in the 70s, I counted a grand total of four white characters onstage, and all of these are men with dubious motives. Of the countless offstage white characters mentioned, they are overwhelmingly cheats, murderers, and rapists, or, as is the case in Jitney, in which a young white woman falsely accuses her Black boyfriend of rape, deadly liars. The widespread white villainy in the plays either did not register with Wilson’s white admirers or did not trouble them. After all, he wasn’t writing about people like them, was he?

At some point in every one of the 10 plays, Black characters engage in a debate that could be boiled down to Personal Agency vs. Systemic Racism. Are they masters of their own destiny or eternally limited in their aspirations by the legacy of slavery? Sometimes the conflict is roiling within a single character. In Two Trains Running, a restaurant manager named Memphis rails against Black Power activists “talking about freedom, justice and equality and don’t know what it mean. You born free. It’s up to you to maintain it.” Yet this same character had to flee the South when a gang of white men wanted to take over land he had bought and paid for. “Got home and they had set fire to my crop,” Memphis recalls. “To get to my house I’d have to walk through fire. I wasn’t ready to do that.”

It’s possible that the “neo-cons and neo-liberals” that Ishmael Reed invoked did not absorb the complexity and ambiguity of the debates among Wilson’s characters when they claimed the playwright as “a member of their ranks.” But for Black Americans, even success is often stigmatized. In March 1996, August Wilson sat at the wooden table in the dark void of the Charlie Rose Show set. “Some have said,” the host drawled unctuously, “that, in a sense, your success keeps other Black playwrights in the shadows,” as if it were somehow Wilson’s fault that he had been anointed the Chosen One by the theater establishment. Wilson looked dismayed by the suggestion and said, “I don’t understand the logic behind that.” Three months later, he would offer a more full-throated response on the situation of Black dramatists in America.

“I am what is known … as a ‘race man,’” August Wilson declared in his keynote address to the Theatrical Communications Group national conference at Princeton University, in June 1996. “That is simply that I believe that race matters—that it is the largest, most identifiable, most important part of our personality.” This pronouncement came after he had, earlier in the speech, cited among his influences, “Marcus Garvey and the Honorable Elijah Muhammad,” two names that Wilson certainly knew would raise the hairs on many an American neck.

He then turned to his métier. “If you do not know, I will tell you,” Wilson said. “Black theater in America is alive, it is vibrant, it is vital … it just isn’t funded.” In the theater world, financial resources were “reserved as privilege to the overwhelming abundance of institutions that preserve, promote, and perpetuate white culture.” As a remedy, he called for the creation and funding of institutions that would be dedicated exclusively to African American works: “We need theaters to develop our playwrights. We need those misguided financial resources to be put to better use. Without theaters we cannot develop our talents.… We need some theaters.”

Wilson went on to criticize the sort of white theatergoers who flocked to his plays, saying “the subscription audience holds theaters hostage to the mediocrity of its tastes, and impedes the further development of an audience for the work that we do.” He added: “While intentional or not, it serves to keep Blacks out of the theater. A subscription audience becomes not a support system but makes the patrons members of a club to which the theater serves as a clubhouse.” Finally, for good measure, Wilson slammed reviewers, most of whom had lavished praise on his work. “A stagnant body of critics,” he said, “operating from the critical criteria of 40 years ago, makes for a stagnant theater without the fresh and abiding influence of contemporary ideas.… The critic who can recognize a German neo-Romantic influence should also be able to recognize an American influence from the blues or Black church rituals.”

The speech was instantly controversial. Perhaps no one was more offended by it than Robert Brustein, then director of the American Repertory Theater at Harvard and drama critic for, ahem, The New Republic. In “The Ground On Which I Stand,” Wilson called out Brustein for suggesting that theatrical institutions were lowering their aesthetic standards in their zeal to produce more culturally diverse works. Wilson stated that “works by minority artists may lead to a raising of standards and a raising of the levels of excellence, but Mr. Brustein cannot allow that possibility.”

Brustein and Wilson went at it in a series of written exchanges in American Theatre magazine. Criticizing the playwright for employing “the language of self-segregation,” Brustein said, “I fear Wilson is displaying a failure of memory—I hesitate to say a failure of gratitude” for the support his work had received in the theater world. Wilson responded: “To suggest that I owe a debt of gratitude to the theaters that have done my work is to suggest my plays are without sufficient merit to warrant their production other than as an act of benevolence.”

The Brustein brouhaha culminated in a public debate at New York’s Town Hall in January 1997, an event that the chattering classes greeted with an excitement usually reserved for Ali-Frazier prizefights. The moderator, Anna Deveare Smith, had to ask for order in the crowd after Brustein mocked Wilson for considering himself “African” and said that the playwright had “probably the best mind of the seventeenth century.” Wilson replied: “These are some of the most outrageous things I’ve ever heard.” After that, the evening got really contentious. You can listen to excerpts of the debate on YouTube.

“The Ground On Which I Stand” was most widely attacked for the opposition August Wilson expressed in it to nontraditional or color-blind casting. “To mount an all-Black production of Death of a Salesman,” he declared, “or any other play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture is to deny us our own humanity, our own history, and the need to make our own investigations from the cultural ground on which we stand as Black Americans.”

Wilson did not mention that he had, in fact, written a brilliant African American retort to Arthur Miller’s masterpiece. It’s called Fences, and the parallels between the two plays are fascinating. Instead of Miller’s lowly Willy Loman, Wilson presented a Black Everyman, the sanitation worker Troy Maxson. Willy is unfaithful to his wife and has a difficult relationship with his athlete son. Ditto for Troy. Both plays end with bittersweet eulogies. And both plays were immediately appreciated, each winning both the Tony Award and the Pulitzer Prize. But Troy Maxson’s American journey is profoundly different from Willy Loman’s, his travails inextricably intertwined with his race. And Loman and Maxson have strikingly opposite views on life. Take, as just one juicy example, Willy’s obsession with being “well-liked.” He tells his sons: “Be liked and you will never want.” By contrast, Troy advises his son: “Don’t you try and go through life worrying about if somebody like you or not. You best be making sure they doing right by you.”

When Paramount Pictures approached Wilson about buying the film rights to Fences, the playwright had a fundamental request, one he used as the title for an op-ed piece he published in The New York Times in 1990: “I Want a Black Director.” As Wilson recounted in the article, his wish was “greeted by blank, vacant stares and the pious shaking of heads as if in response to my unfortunate naiveté.” Wilson even turned down “a well-known, highly respected” white filmmaker. “White directors are not qualified for the job,” he insisted. “The job requires someone who shares the specifics of the culture of Black Americans.” August Wilson stuck to his guns. And when he died 15 years later, none of his plays had been turned into movies.

Today, Wilson’s decision to hold out is reaping luscious fruit. In 2010, Denzel Washington starred in a Broadway revival of Fences, bringing a febrile energy to the role of Troy Maxson, reimagining James Earl Jones’s original, more somber, and seemingly definitive portrayal. Wilson’s widow, Constanza Romero, approached Washington about a film adaptation. At last, Wilson would get his Black director. Arguably the all-time biggest Black star of stage and screen, Washington had won his first Oscar for playing a runaway slave turned Union soldier in Glory and had incarnated Malcolm X. He had portrayed not only action heroes but also (Hooray for nontraditional casting!) Richard III. The film version of Fences that he starred in and directed is a master class in “opening up” a piece of theater. With clever changes of settings and dynamic camera work and editing, Washington made the stagiest of dramas thrillingly cinematic. He also respected the cultural integrity of Wilson’s work. The playwright’s estate has entrusted him to produce film versions of all 10 plays in the Century Cycle.

The second film adaptation, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, features Viola Davis in a bravura performance as the title character, “the Mother of the Blues.” Davis has become the preeminent interpreter of Wilson’s women. She won her first Tony Award for playing the fiery Tonya in King Hedley II (set in 1985) and nabbed a Tony and an Oscar for her portrayal of Troy’s wife, Rose, the most soulful of the wounded warriors in the Maxson family battleground, in Fences. In addition to her towering talent, Viola has the most expressive pair of eyes in American cinema since that other dazzling Davis: Bette.

Most of the film’s action takes place in a Chicago recording studio on a sweltering day in 1927. Ma Rainey and her four-man band are scheduled to record several tracks, including the song that Wilson took as the title of his play. As in all of Wilson’s Cycle, the script is bursting with sublime language: boasting and jiving, tall tales and philosophical debates, angry clashes and painful confessions, all rendered with an uncanny eloquence that is uniquely African American. Wilson garners tremendous suspense from the power struggle between Ma Rainey and the two white men who are ostensibly in charge of the recording session. Throughout the long, hot afternoon, the blues singer wages a battle for both her artistic integrity and her personal dignity. “They don’t care nothing about me,” she says of her manager and the record company chief. “All they want is my voice. Well, I done learned that, and they gonna treat me like I want to be treated no matter how much it hurt them.”

The leaders of the Ma Rainey creative team embody August Wilson’s vision of Black self-determination in the arts. The film’s director, George C. Wolfe, began his long and distinguished theatrical career with the piquant satire The Colored Museum and the musical drama Jelly’s Last Jam, about jazzman Jelly Roll Morton. The screenwriter, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, was a frequent Wilson collaborator. While remaining faithful to Wilson’s text, they have added a prologue and an epilogue to the film version that only enhance the power of the work. The casting of Glynn Turman as the pianist Toledo will warm the hearts of Black film lovers who have revered the actor since his role in the 1975 classic Cooley High. Finally, after portraying such Black icons as Thurgood Marshall, Jackie Robinson, James Brown, and the superhero T’Challa, Chadwick Boseman capped his career with a scorching performance as the trumpeter Levee, his last appearance on-screen before his tragic death at 43.

By insisting on a Black director for a movie adaptation, August Wilson proved himself to be as much of a badass as his Ma Rainey, who knows that, aside from her talent, her greatest power as an artist is the power to say “no,” and to keep on saying it, until she gets exactly what she wants. As producer of the Century Cycle, Washington has approached an array of acclaimed Black directors, including Ava DuVernay, Ryan Coogler, and Barry Jenkins, to helm future adaptations.

Thanks to the movies, people worldwide will get to discover August Wilson’s extraordinary poetry, grounded in the intensity of his listening to his Black elders in Pittsburgh. In his introduction to Seven Guitars (set in 1948), he paid tribute to his mother, Daisy, saying that the everyday content of her life was “worthy of art.” During that heated Town Hall debate in 1997, an audience member asked August Wilson about his mixed racial heritage, in effect, raising the specter of Frederick Kittel Sr. The playwright’s response was swift and to the point: “My father was German. What about it? … The cultural environment of my life is Black. I make the self-definition of myself as a Black man, and that’s all anyone needs to know.”