In October, The New York Times published an opinion essay by Berkeley law professor (and law school dean) Erwin Chemerinsky originally titled “Amy Coney Barrett’s Originalism Threatens Our Freedoms.” Chemerinsky took aim at the fossilizing impact of “originalism,” the conservative theory of constitutional jurisprudence that declares that only the literal meaning of the Constitution’s text, along with what we know about the “intent” of the Founders, can guide the courts when they interpret laws.

The case against originalism is all too familiar. As Chemerinsky and other legal scholars have emphasized, arguments for an originalist jurisprudence have always rested on flimsy foundations, more in the realm of myth than of practical realities and vulnerable at all times to the charge of anachronism, that “rights in the twenty-first century should not be determined by the understandings and views of centuries ago.”

Even early jurists, such as John Marshall—who served as chief justice of the Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835—believed the Constitution must adapt to “the various crises of human affairs” if it were to endure. Marshall was close enough to the circumstances of the drafting and ratification of the Constitution to appreciate that no original public meaning existed for most provisions of the Constitution because—as historians of the founding, such as Gordon Wood and Pauline Maier, also tell us—those present at the creation themselves agreed on so little. Like the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution itself was a set of compromises.

Originalist methods break down even if one accepts the existence of some coherent public sense of the meaning of the Constitution. We know that federal judges can be scientifically and technologically befuddled, which means that the precepts of originalism merely compound the fecklessness of efforts to negotiate the effects of postindustrial technologies on rights first imagined in a bygone, preindustrial era.

Conservative judges will, in any event, ignore original meanings when it suits their purposes, as with Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, which, on a 5–4 vote, struck down key provisions of the Voting Rights Act as a violation of the principle that Congress must treat all states alike. As Chemerinsky reminds us, no such requirement exists in the Constitution, and there is no subsequent precedent for it.

What is remarkable is that even legal conservatives like Harvard constitutional law professor Adrian Vermeule now concede these obvious failings of originalism. Vermeule (echoing, with some irony, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan) has said that “we are all originalists now,” endlessly litigating “dubious claims about events centuries in the past.” The time has arrived, Vermeule insists, to move beyond originalism’s putatively neutral precepts to embrace a morality-infused “common-good constitutionalism.” According to Vermeule, the doctrine has “outlived its utility, and has become an obstacle to the development of a robust, substantively conservative approach to constitutional law and interpretation.”

It turns out that originalism’s real utility is its transactional value as a vehicle for other legal principles. The deeper structure of constitutional jurisprudence is the pervasive and foundational but largely unacknowledged influence of Catholic natural law moral philosophy. Barrett represents more than simply the latest link in the chain of custody for originalist jurisprudence that extends from her mentor, and one of originalism’s founding fathers, former Justice Antonin Scalia, to the present day. As a Catholic and an intellectual descendant of decades of Catholic influence on conservative legal circles, she also represents the alarming future of the conservative legal project.

Conversations on religious influences in American public life typically have focused on white evangelical Protestant support for Donald Trump and the Christian nationalist wing of the Republican Party. However, the rise of American conservatism is actually a 50-year saga of Catholic intellectual and theological penetration of the halls of power.

By some measures, Catholicism has flexibly accommodated itself to the shifting demographic and cultural realities of our time. Pope Francis is the first non-European Pope since the eighth century and, while by no means as radical as his opponents claim, he has worked diligently to promote the Church’s mission globally and to shift the focus of the Church to the existential challenges the planet now faces. On January 20, Joe Biden also was sworn in as the second Roman Catholic American president.

It may thus seem surprising that Catholicism, despite its waning moral and spiritual credibility, cratering populations of priests, and shrinking appeal to younger white Americans, is today the linchpin of culture-war conservatism in the United States. The underlying organizational and intellectual impetus for this influence derives from Thomist Catholic perspectives—on natural law, in particular—that have achieved resurgence in the last 50 years and have infused conservative foundations and think tanks alongside vast amounts of donor money.

Roman Catholic influence in American politics and media began to mushroom in response to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and, more specifically, to the crisis engendered by the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision (there was also the heartland resistance in the 1970s, organized by Catholic conservative Phyllis Schlafly, to ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment). Conservative precepts of Roman Catholic theology apply specifically to “religious liberty” commitments and to “human life” and “human dignity” issues associated with reproductive, sexual, and gender politics. However, in recent decades these precepts have also reinforced an identity politics organized around shared racial, ethnic, and religious origins, with specific reference to the European, medieval, Christian-Catholic foundations of Western civilization and Western values. Traditionalist Catholic ideas and values now interpenetrate conservative American political thought and nearly every political institution of consequence.

Members of Congress are increasingly Catholic, especially in the Republican Party. As of the 2016 election, representation of Catholics in Congress had increased by a remarkable 68 percent since 1960, from 100 to 168, a total in excess of 31 percent of Congress (even as Catholics nationally have declined to 21 percent of the population, fewer than the 23 percent who in 2014 declared “None” as their religious affiliation). Between the 2008 and 2016 elections, the cohort of Catholic House Republicans nearly doubled, from 37 to 70, while the number of Catholic House Democrats fell from 98 to 74. Despite this significant Catholic overrepresentation in Congress, traditionalist Catholics—for whom the nineteenth-century Blaine Amendments, by which states sought to bar public funding of religious education, remain the bloody shirt they cannot stop waving—mewl incessantly about ongoing prejudice and discrimination.

Catholics are even more overrepresented in the judiciary. Nearly 30 percent of judges serving on the federal bench are Catholic. Six Catholics presently serve as justices on the Supreme Court, five of whom are Republican-appointed conservatives. A seventh, Neil Gorsuch, is a formerly devout Catholic who now worships as an Episcopalian. Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy, the justices Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh replaced, were also Catholic. Which means nine of the most recent 13 justices have a Catholic background.

Prior to the appointment of Scalia to the Supreme Court in 1986, only seven of the 102 justices serving the previous 197 years of the Court’s history had been Catholic (the first being Roger Taney, appointed by Andrew Jackson in 1836).

How did this happen? In 2005, following the nominations of Supreme Court Justices Roberts and Alito, Pew Research’s Luis Lugo, emphasizing the perspective of evangelical scholar Michael Cromartie, observed that what the “intellectual disaster” of evangelical Protestantism lacked was a robust natural law tradition, and “that’s where the Catholics have the leg up.” Lugo remarked, “That’s why in terms of public discourse, but also with respect to the judiciary, they’re often much more sophisticated in how they handle this.” During the 1990s, for example, evangelical Protestants such as Ralph Reed filled their organizations with Catholics as a way to close these cavernous gaps in their own intellectual traditions.

In other words, the ascendance of conservative Catholicism in American politics did not happen by accident.

Garry Wills’s 1972 book about the trials of the Catholic Church during the turbulent 1960s paired Pope John XXIII and John F. Kennedy in a chapter titled, “The Two Johns—Rome and the Secular City.” In our story, we have the three Leos—nineteenth-century Pope Leo XIII, twentieth-century German-American philosopher Leo Strauss, and twenty-first-century Federalist Society impresario Leonard Leo—and their contributions to the conservative Catholic conquest of the federal courts.

Pope Leo XIII, arguably the most influential pope since the Reformation, linked modernism to the collapse of philosophical rigor that accompanied the heresies of sixteenth-century Protestant religious reformers and humanists, whom he termed “struggling innovators.” In this lax era, he said, philosophers speculated without regard to any unifying system. Their ideas multiplied “beyond measure,” leading to “false conclusions concerning divine and human things.” In a stunning Counter-Reformation sally, Leo’s 1879 encyclical, Aeterni Patris (On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy), refocused attention on the thirteenth-century “Angelic Doctor” Thomas Aquinas. Leo vocalized the importance, for the survival of the Catholic Magisterium, of systematic, intellectually rigorous approaches to philosophy and theology characteristic of medieval scholasticism.

Leo made it possible—with profound political consequences—for Thomist natural law moral philosophy to become a powerful alternative to the reigning modalities of Enlightenment rationalism, skeptical modernism, and transactional liberalism. Two decades after Aeterni Patris, Leo’s 1899 pontifical letter to Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons, Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae, focused provocatively on the heresy of “Americanism.” He specifically called out the special (or exceptional) character of the American experience as a post-Reformation nation. Lacking Catholic and medieval spiritual foundations, he averred, the U.S. had been too free in its cultural imagination to indulge limitless self-fashioning and heedless reinvention of the sort Leo attributed to Reformation innovators. For Leo, the defects of Americanism aroused suspicions that “there are among you some who conceive and would have the Church in America to be different from what it is in the rest of the world.” “But the true church is one,” Leo warned, “as by unity of doctrine, so by unity of government.”

As a shot across the bow of the American Catholic episcopacy, Testem Benevolentiae established universal spiritual, moral, and governance expectations concerning the unyielding “shalts” and “shalt nots” derived from both revelation and natural law. Previously inaccessible, and even beyond the realm of awareness, to the modernist culture and aspirations of American life, these universal expectations materialized a doorway to the medieval past, which in the U.S. had never before existed.

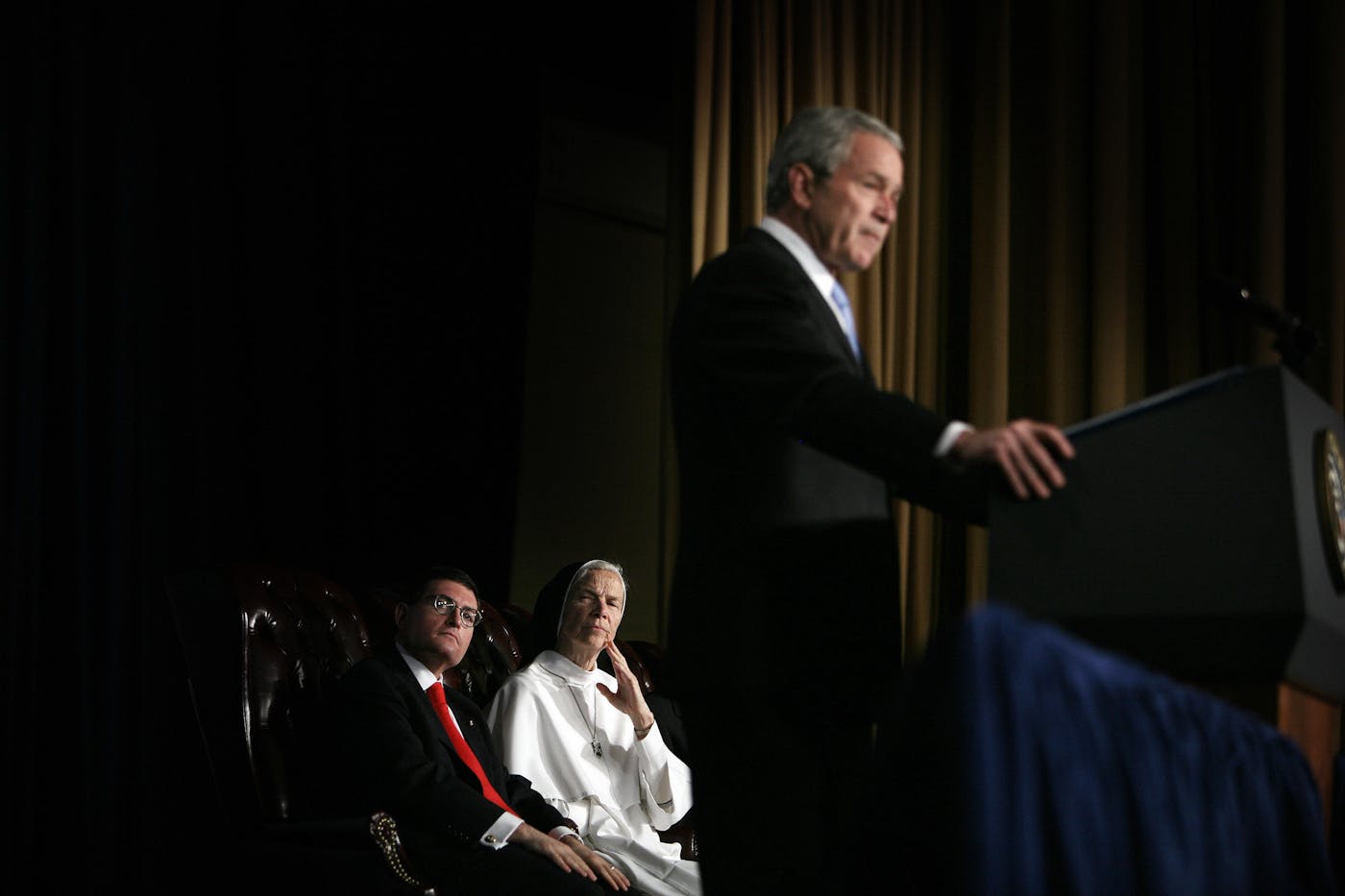

Following World War II, Catholic perspectives informed the pontification of Cold War conservative intellectuals. William F. Buckley, the devout and mystically inclined Catholic, remains for many the father of modern conservative ideology, defending both faith and markets from the secular and statist threats of godless communism. At the same time, conservative philosophers established an institutional academic presence in diverse locations, including the University of Chicago, where our second Leo—Leo Strauss—held court, and also at tradition-minded Catholic colleges and universities such as the Catholic University of America, Georgetown University, and Notre Dame.

The textualist methods pioneered by Strauss burrowed deeply into the meaning of foundational philosophical works, based on the conviction that these manuscripts contained timeless truths about human nature and human relationships and obviated need for historical situation. Strauss’s relationship to Catholicism itself remains oblique and complicated, but there is no doubt about the affinities between his approach to philosophy—specifically his ideas about natural right and natural law—and the efforts of Thomists to reclaim classical philosophy and reason on behalf of the higher imperatives of revelation, a mission indispensable for maintaining the terrestrial power of the Church.

Strauss himself was not overtly political in relation to pressing matters of his time. However, other Straussian scholars did make more historically specific (and politically directed) claims about how classical and Christian conceptions informed the founding ideals of nationhood in the U.S. Such deductions became the basis for theorizing by political philosophers such as Harry Jaffa (one of Leo Strauss’s first Ph.D. students)* about the American nation’s exceptional world-historical status, derived from its embodiment of the principles of natural law and free markets.

In recent decades, legal conservatives have reaped the rewards of the spadework done by this older generation of academic political philosophers. The precepts of originalism and textualism reinforce the Straussian focus on foundation texts, the timeless universality of frozen language, and moral dissipation.

During the 1970s and 1980s, superwealthy American businessmen such as Charles Koch began systematically to funnel vast amounts of money into foundations and think tanks explicitly designed to influence public opinion, public policy, and public morals. While much of this wealth funded libertarian policy organizations like the Cato Institute, contributors also generously funded development of policy organizations infused with a neo-Thomist faith-based philosophy designed to moor the conservative political insurgency spiritually.

The Federalist Society is one of the most notorious policy institutes to benefit from these infusions, internalizing and propagating the baseline precepts of culture-war Catholicism. The Society was founded in 1982 as a seedbed for nurturing conservative legal principles among students at otherwise “liberal” law schools. Early supporters included Antonin Scalia and Attorney General Edwin Meese, whose chief speechwriter, a Straussian constitutional scholar named Gary L. McDowell, drafted speeches for Meese calling for a return to “a jurisprudence of original intent.”

Which brings us to our third Leo. The Federalist Society’s former executive vice president, Leonard Leo, shepherded the Supreme Court Senate confirmations of Justices Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett. The grandson of a Brooks Brothers vice president, Leo is, as Jeffrey Toobin wrote, a bella figura of the legal conservative movement, well accoutred and unflappable. Toobin also noted that Leonard Leo’s life “has been shaped as much by Catholicism as by conservatism.” Indeed, there is more than a trace of Cardinal Wolsey, stepping out of Hilary Mantel’s novel Wolf Hall, in the style and confidence with which Leonard Leo comports himself.

The Federalist Society has specifically anchored itself to a fideist commitment to constitutional originalism and textualism—what we might term an Abrahamic fetish of the text as revelation. However, the Federalist Society—along with judicial advocacy offshoots, such as the Judicial Crisis Network and Becket Fund for Religious Liberty—also possesses an ingrained belief in the natural law as precursor to and ultimate measure of positive law, leading ultimately to the backbreaking efforts of many legal philosophers to claim the Constitution itself fully conforms to Thomist natural law precepts. The organization’s legal focus has made it an ideal vehicle for representing revanchist Christian values in the courtroom and in other public venues concerned with legal philosophy and jurisprudence.

The moral philosophy of natural law absorbs (from revelation and scripture) and communicates (into public discourse and legal practice) a quite specific understanding of the human individual as the summit of God’s creation, shaped in the image of God himself. Ideas about natural law date back nearly 800 years to the grand synthesis of Aristotle and Augustine in the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas. These ideas assume intrinsic rational capacities of humans to properly perceive and pursue uniquely human goods and to deduce from these goods a system of moral precepts and ethics that become the framework for elucidating and codifying positive law. As Thomas wrote, “This is the first precept of law, that ‘good is to be done and pursued, and evil is to be avoided.’ All other precepts of the natural law are based upon this: so that whatever the practical reason naturally apprehends as man’s good (or evil) belongs to the precepts of the natural law as something to be done or avoided.”

Despite these Christian-Catholic origins, natural law philosophy was for centuries theologically agnostic, pursuing optimistic, forward-looking agendas that engaged and embraced the “self-evident” reality of social change. Beneath such open skies, natural law philosophy ranged broadly and ambitiously across the spectrum of evolving human circumstances and needs to encompass notions of sin, international law, the right to revolution and self-determination, the abolition of slavery, social justice, civil rights, universal human rights, free-market economics, and conservative historiography. Catholic natural law precepts infused the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the adoption of which represented, in some sense, an arrival of a Catholic moral perspective positioned to sweep away the more retrograde baggage of the Church associated in prior decades with fascist and Nazi regimes across Europe.

However, Catholic theorizing about natural law swung hard right in the 1960s, assuming a new and more sinister synthesis in the “new” natural law, or NNL, that emerged from the religious and political turmoil of the 1960s. The NNL—which received its most precise articulation from Anglo-American theologians and philosophers such as Germain Grisez, John Finnis, Hadley Arkes, and Robert P. George—hardly resembled the less systematic and more discursive applications of Thomist natural law from prior centuries.

At this time, natural law philosophy transformed itself from a flexible and modular set of ideas for adapting to shifting historical realities into a rigid, reactionary, punitive, and self-righteous propaganda platform for the most conservative elements of the Catholic Church and its intellectual apologists. Upon these foundations, NNL voiced a cramped and twisted conception of human universality that begins and ends with sexual morality, returning to traditional Catholic obsessions with sexual deviance, family collapse, and social disorder. Indeed, NNL unapologetically echoed and amplified the concupiscent obsession of medieval Church inquisitors with “the most heinous of all possible crimes: perverted, filthy sex.”

In what will be remembered as one of the least defensible readings of recent history, 93-year-old Joseph Ratzinger (the conservative Catholic prelate also known as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) in 2019 blamed the moral disconnection and sexual depravity of the 1960s for the priestly scourge of child sexual abuse ravaging the Catholic Church since at least the 1950s. Similarly self-consumed by the overheated sensibilities of the ’60s, the moral philosopher Germain Grisez—sensing opportunity in the rancorous debate about contraception within the Church at that time—stepped in to fill this breach with a prodigious output of scholarship culminating, some 20 years later, in his The Way of the Lord Jesus, a compendium of pastoral guidance on all questions that touch upon the religious faith and obedience of Catholics (including weirdly specific and technically explicit sexual instructions for believers).

This new natural law, as Grisez first formulated it, constituted a moral philosophy based on the vision of an ordered love governing the thoughts and deeds of humans. Indeed, the psychic comforts of well-ordered environments pervade NNL, with everyone and everything occupying their proper place within the medieval great chain of being constituting the preeminent good. In almost symmetrical counterpoint to the loosening of sexual morality in the 1960s, then, Grisez tightened the screws. Despite an ostensibly broad focus on the shared goods all humans might rightly seek in order to flourish, Grisez actually shrank and concentrated the scope of natural law moral philosophy to a sexual catechism serving this highest human good: species procreation.

For NNL proponents, the most basic and unassailable human good is procreation. The choices “to contracept” and “to abort” are disordered forms of hatred that violate this ultimate good “and as such can never be justified.” In this foundation precept of NNL, Grisez anticipated the 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae, termed by some “the most important papal document since the Reformation,” which unconditionally condemned any use of contraception by Catholics. Upon this foundation of reaction to the promiscuity of the times, Grisez and those who followed labored to explain, improve, and proselytize tenets of the NNL, fortifying it as a dam against surging and interlaced global tides of sexual immorality, cultural debauchery, and infant murder.

The intellectual commitments and moral sensibilities of the new natural law have in recent decades penetrated many of the nation’s most significant media, political, legal, and educational institutions. NNL has passed seamlessly into the conservative intellectual bloodstream via organizations closely attached to the Federalist Society—such as the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.; the Witherspoon Institute and James Madison Program at Princeton; the Acton Institute in Grand Rapids, Michigan; and the Claremont Institute in Southern California. With their cosmological certitudes about the fixed nature of God’s creations and their procrustean allegiance to the “original intentions” of divine and human creators and founders alike, NNL moral philosophers have on this foundation constructed an intellectual scaffolding that has inspired powerful critiques of liberalism and modernity and sustained and strengthened the originalist jurisprudence of the legal conservative movement.

To locate the mediating institution that best captures the populist allure of these traditionalist (and sexually demarcated) religious sensibilities, we need look no further than Fox News. In the Trump years, Fox impressively distilled, channeled, and mainlined the inarticulate but bitterly felt grievances of its audience—significantly older, poorly educated, ethnically European—directly to the president, who echoed back and amplified the grievances of this belligerent culture-war base. The newsroom at Fox characterized its typical viewer as “an Irish-Catholic family man,” the archetypal police officer or firefighter living on Staten Island or Long Island. Through this lens, what we see on Fox is a purified form of culture-war Catholicism that is fully and explicitly an identity.

While Fox is not explicitly religious, the network both supports and conceals a far more extensive religious media ecosystem integral to the political strategy and program of the Republican Party since the 1980s. This ecosystem functions as the link between the sophisticated theory of natural law and originalist legal conservatives and the vast swaths of the nation excluded from, alienated by, and hostile to the mainstream liberal media.

The conservative Catholic media universe is a high tower atop a broad base espousing a traditionalist Catholic message—including the voice of some of the most extreme Catholic opponents of Pope Francis. The base consists of the Eternal Word Television Network (known to all as EWTN) and its affiliates, the National Catholic Register and the Catholic News Agency. EWTN advertises itself as the largest religious media network in the world, with a global reach of 310 million television households. It has 6,000 television station affiliates, over 500 radio station affiliates, satellite and cable broadcasting, and the world’s most trafficked Catholic website. White Catholic voters, especially those who regularly attend religious services—the prototypical EWTN viewer—overwhelmingly supported Trump in 2016. Other extreme and edgy publications carrying the Catholic fundamentalist message include Life Site and Church Militant.

In the tower reside a constellation of highbrow Catholic-inflected intellectual journals—among them, National Review, Public Discourse, First Things, New Oxford Review, and The Josias—dedicated to spinning filigreed philosophical arguments on behalf of conservative theological and culture-war positions informed by the new natural law. In these publications, one routinely encounters the carefully wrought, portentous words of NNL proponents such as George Weigel, Robby George, and William Barr—a full Catholic roster of waggish music nerds in finely tailored suits, bella figuras all.

In 2019, First Things, the most intellectually serious and influential journal of the religious right, blew up the debate about the future of the conservative movement. In two articles published early in the year, the magazine—which is nominally ecumenical but essentially Catholic—challenged the “dead consensus” of American conservatism that has prevailed since the 1950s and achieved its apotheosis in the Reagan years, the grand fusion of intellectual commitments to free markets, anti-communism, and traditional family values.

The first of these articles, “Against the Dead Consensus,” published in March, was a manifesto signed by 15 academics and public intellectuals, 14 men and one woman, a few quite well known (Patrick Deneen, Rod Dreher), the remainder more obscure, but all sharing a commitment to Catholic communitarian (or “common-good”) principles associated with Notre Dame natural law philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. This manifesto repudiated the post–World War II conservative consensus for collapsing, in our neoliberal era, into a libertarian obscurantism, emphasizing individual autonomy at the expense of connection and community, forgetting about the cultural foundations of a truly preservationist “conservatism,” and so ultimately devolving into an echo of liberalism itself, helpless against the rapacious and morally untenable onslaught of the liberal left.

Two months later, First Things dropped another bomb with the publication of an article titled (weirdly but memorably) “Against David French-ism,” written by New York Post opinion page editor, Iranian-American Catholic convert, and enfant terrible Sohrab Ahmari. In this essay, occasioned by a Facebook ad for a children’s reading hour with a drag queen at a public library in Sacramento, California, Ahmari called out fellow Christian conservative, National Review writer, and Never-Trump stalwart David French as the personification of this dead consensus.

Ahmari’s auto-da-fé enthralled the intellectual architects of our contemporary Counter-Reformation, clearing space for an unapologetic embrace of the scorched-earth political theology of Catholic integralism. This Catholic form of revanchism would obliterate church-state barriers and superimpose a terrestrial layer of morality and control, under the auspices of natural law, to root out deviance and knit together the republic.

On the surface, it might seem odd that Ahmari would pick on David French, a longtime litigator on behalf of religious liberty with impeccable conservative credentials. But French turned out to be both an easy and logical target because of what Ahmari refers to as his “politeness,” which evinced ignorance about, and weakness against, the culture warriors on the left. An avatar of the dead consensus, a “squishy” conservative, a “hazy” originalist, French had argued that religious conservatives must win their battles rhetorically, within a marketplace of ideas, the presumption being that neutral political institutions will at least guarantee a fair fight.

There is no doubt that what Ahmari aptly termed Trump’s “animal instinct”—his feral will never to “go around” but always to “go through,” to beat his opponents to a pulp—offered a permission structure to abandon democracy and embrace autocracy, which conservatives seized upon to challenge the consensus foundations of American politics. Thus liberated from the consensus carapace, the First Things conservatives aimed not-very-friendly fire at brethren who remained committed to a “neutral space” preserved by public institutions built to negotiate and adjudicate conflicts in a pluralistic society between groups with otherwise incommensurable private sphere commitments (e.g., “wedding cake baker and gay marriage maker”).

Many of us would identify this idea of a neutral space with civil society itself. However, postconsensus Catholic conservatives like Ahmari and Vermeule argue that a neutral space is itself a fantasy, with non-infrequent invocations of German Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt’s view that politics is war by a different name, an all-consuming battle in which friends can quickly become enemies. As Ahmari has stated, politics requires conservatives “to fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good.”

Russell Shaw, Germain Grisez’s Boswell, pointedly wrote, in tribute, that we are all now “students of Grisez.” No one better epitomizes Grisez’s influence than Adrian Vermeule, who now stands athwart the palisades of a new conservative legal empire, surveying with satisfaction its crushing defeat of “legal liberalism” but yearning already for the next crusade.

Many observers, on both the right and the left, have dismissed Vermeule’s “common-good” notions of constitutionalism as performative melodrama or merely as the antics of a troll out to get the liberal goat. But his intellectual self-confidence clearly speaks to the tattered, moth-eaten state of the consensus that has historically sheltered process-driven, Enlightenment liberalism. What First Things editor R.R. Reno has approvingly observed about Ahmari applies equally to Vermeule: “He sees auspicious signs in today’s polarized political landscape, opportunities for fresh initiatives rather than peril and persecution.”

Since his own 2016 “no middle way” Catholic conversion moment, Vermeule has unhinged himself on behalf of integralism. Inspired by Pope Leo XIII’s 1892 encyclical, Au Milieu des Sollicitudes (On the Church and State in France), he urges Catholics to work strategically within the liberal political order. The goal of this effort is not merely (and naïvely) to achieve a French-fried accommodation to liberalism. Instead, Catholics must fully (and strategically) strive toward the long-term aim of superseding altogether the liberal polity, through the establishment of an integrally Catholic state that recognizes the superiority of spiritual over temporal authority.

This is the integralist position in a nutshell, but Vermeule remains distracted by the possibility that liberalism’s proceduralist and parliamentary forms of participation and discourse will “suborn” or corrupt the Catholic mission. Inspired by Carl Schmitt, Vermeule posits a premodern organizational alternative that would inure Catholics from this risk of subornment, a passage through to the integral state facilitated not by elections and parliaments but by executive bureaucracies. Vermeule tells us that “the ideal-type principles of hierarchy and unity of top-level command that animate bureaucracy, especially but not only military and security bureaucracies, are not obviously the sort of principles that threaten to inscribe liberalism within the hearts and minds of participants.” He chuckles at Carl Schmitt’s suggestion that Anglo-Saxon Protestants recoil from the Catholic Church because it is a “celibate bureaucracy.”

In the idea that liberalism corrupts and suborns, Vermeule shares much with his friend, the conservative Catholic political philosopher Patrick Deneen. Both Vermeule and Deneen regret how conservative Supreme Court justices arrive in Washington and—their minds occluded by its swamp-water—seem invariably to “defect” at key moments from their conservative principles and fall captive to the values of “gentry liberals”—the elite, effete, half-formed urban professionals of blue America who have parasitized and rotted out society’s governing institutions. For Deneen, Barrett’s most sublime qualification therefore seems to be that blue America, that unclean thing, remains alien to her.

Instead, she will have been dominantly shaped by the schools and surroundings of “red America.” She will be the first justice to receive her law degree from a Catholic university. She has spent almost her entire life in the “flyover” places of America where “gentry liberalism” is not the dominant fashion. Rather, she has either been born into, or sought out, places where a different ethos reigns: family, home, place, tradition, community, and memory.

Deneen here travels to the heart of the culture war that NNL philosophers and political integralists have so cleverly exploited to gain the upper hand in American law. The natural law is ultimately not about human universals but about geographic particulars. The backdrop to this often-abstruse philosophical debate is a story that begins with the enduring fault lines of racial and ethnic divisions in the U.S., setting in high relief a dark vision of human nature that betrays terror (projected or otherwise) about the “blue America” chaos and violence that simmer just beneath the surfaces of our “red America” lives.

What we’re therefore witnessing in our current moment—whether via “originalist jurisprudence” or “common-good constitutionalism” or “Catholic integralism”—is not merely a continuation of the civilizational battle against “modernism” waged by Christian conservatives since the late nineteenth century (the struggle that gave rise to the Catholic heresy of “Americanism”). In the twenty-first century, the forces challenging the modernist ideal in America are now led—and decisively so—by conservative Catholics, not evangelical Protestants, with a new focus on claiming influence and power via America’s legal institutions, particularly the federal courts.

Going forward, what this means is that the traditionalist Catholic cosmology—with its foundation in Thomist natural law moral philosophy—now prevails and dominates among religious and cultural conservatives, within the law schools and in the courts, heightening the inherent tension of this medieval cosmology with the Protestant and Enlightenment foundations of the American political system.

Catholic conservative philosophers who reject the dead consensus are indeed probing beyond the unsatisfying connotations of a merely “illiberal” ideology. They have begun to define and detail a new postliberal vision of what American society would look like stripped of its current impediments and illuminated by medieval precedents supported by practical reason and the natural law. They can, with striking optimism, imagine how the federal courts, which they now largely control, might enable this “back to the future” journey by moving beyond the recent triumphs of originalist jurisprudence to embrace a spiritually informed constitutionalism that retains its commitments to Thomist natural law while jettisoning originalism’s unnatural and disingenuous reliance on “dead texts.”

Some might argue that this war within the Republican Party shifts advantage back to the Democrats. However, the contest between proponents of originalism and common-good constitutionalism actually signals how rapidly and completely liberals have lost their grip on—and indeed barely comprehend—the national conversation. Because originalism and common-good constitutionalism, despite their differences, remain two sides of the same coin demarcated in a medieval currency that post-Reformation consensus liberals have never previously learned to trade.

Traditionalists within the Church and the Republican Party have locked the nation into a legal framework that has solidified the assumptions of Thomist natural law. We are all now students of Germain Grisez because originalists and integralists alike view the application of Thomist natural law within this legal framework in terms of the “new natural law” formulated by Grisez and his followers, its sexual and reproductive catechism the centerpiece of constitutional jurisprudence and culture warfare.

The moral architecture of the laws of nature cataloged in the Thomist Summa may, after all, merely disclose what we stand to lose in our lives, not what we stand to gain. We never stop falling. In this sense, the natural law claims, for traditionalist Catholics, not grace or justification but power—zero-sum, terrestrial control of both bodies and minds that shields them from the terror of an infinite, God-emptied universe.

*A previous version of this article stated that Harry Jaffa studied under Leo Strauss at the University of Chicago. It was the New School of Social Research.