“I think that the TNT is about to go off.” An Oregon woman named Jo Rae Perkins was livestreaming to Facebook at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, sipping occasionally from a metal water bottle so as not to be interrupted and told to put on her mask, as Covid-19 protocols there now mandate. “I want you guys to please be alert, please be aware—please be prepared.”

Perkins was dressed in a chartreuse mock neck top, with matching chartreuse dangling crystal earrings and thickish lines of cobalt drawn on her upper lash line. She was reflecting on the attempted occupation of the Capitol the day before, January 6, 2021. “All you-know-what is going to break loose. We are not going to lose our country.” A young child’s voice floated over the stream as Perkins greeted some people who just logged on at a rapid clip. “Hello Amy, hey Jeff, Tina, and Darren.” She asked for prayers, and then predicted: “Do not be surprised if martial law happens in the next few days.” Now is the time to gather food and water, Perkins advised, and don’t be surprised if social media goes down. “After yesterday, with Mrs. Babbitt being murdered, that was the shot heard around the world for the second American Revolution.”

About two months before declaring from Sea-Tac that the revolution was here, Perkins won 912,814 votes in her race to represent Oregon in the U.S. Senate. That was close to the total number of votes Trump received in the state. Perkins had stunned national political observers earlier in 2020, when she won the Republican primary, beating out three other candidates. That result perhaps gives a more clear sign of her hard-core base of support: 178,004, just below 50 percent of the GOP primary vote. What had shocked whatever remains of the Republican establishment was Perkins’s avowed, enthusiastic support for the right-wing conspiracy cult QAnon, which places Donald Trump and select government insiders at the center of a crusade against pedophiles and sex traffickers imagined to secretly wield power over America. “Together, we can save the Republic,” Perkins pledged to her supporters after her primary victory. She called her opponent, Senator Jeff Merkley, a “traitor.” The lines were drawn in ways that would become only more clear as the year wore on.

At the time of Perkins’s upset primary win, in May, it seemed unlikely that a believer in QAnon’s constellation of antisemitic and increasingly apocalyptic conspiracy theories could be elected to Congress. Yet she was one of two dozen or so QAnon-affiliated candidates who would appear on the ballot on November 3. (Two, Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, and Burgess Owens of Utah, are now sitting members of the House of Representatives.)

The gradual fusion of Q paranoia and standard Republican political organizing was a leitmotif of the Perkins campaign. In September, a Perkins for Senate fundraiser at Volcanoes Stadium in Keizer, Oregon, doubled as a QAnon road show. Under a smoky sky, from wildfires days before, around 50 people paid between $20 and $100 each, as Tess Riski reported for Willamette Week, to hear Perkins speak, alongside Shady Grooove, a host of the since-removed YouTube channel InTheMatrixxx, popular with QAnon followers, and Captain Roy Davis, author of the books QAnon and the Great Awakening and White Hats, Swamp Creatures and QAnon: A Who’s Who of Spygate. When the Marion County GOP advertised the event on its website, party publicists called Davis “a best-selling author closely associated with QAnon,” with the word “QAnon” linking to a New York Times story titled “G.O.P. Voters Back QAnon Conspiracy Promoter for U.S. Senate.”

“Grooove wasted no time telling the audience that QAnon was a nameless, faceless organization that would protect its ‘digital soldiers,’ as civil unrest escalated after Election Day,” wrote Riski. With words echoing the usual QAnon liturgy about the sacred cause of liberty and the patriots rising up in its defense, Grooove told the people at the fundraiser, “I am one of those people who would be willing to go anywhere Donald Trump sent me because I believe this man is fighting for us.” Grooove claimed, in the tradition of prophecy, that a great reckoning loomed: “This is not gonna end on Nov. 3. And I’m here to tell you this, and I want to prepare you for it. It’s not going to end on Nov. 3. It’s going to continue. How long it continues? It’s up to us.”

QAnon influencers such as Shady Grooove have helped bring the movement’s theology to a far broader audience. Before he was stumping for a congressional candidate, he had built a burgeoning following on Twitter and YouTube. He and other social media brand names spread the messages attributed to Q—the apocryphal highly placed government official at the center of all the unhinged intrigue—from lesser-known image boards like 8kun. They posted musings on the meaning of bread crumbs (as followers have dubbed these gnomic dispatches from Q) to their own social media platforms, putting them in front of yet more followers, who can chew them over and share them again. QAnon takes every platitude about the internet democratizing the media and marries it to the far more instrumental cult of the personal brand. It generates more “truths” than can be true—and, for a few, a kind of celebrity.

Perkins participates in this media and meaning-making, too. Her airport call, soberly alerting Q believers to the next phase of the storm (as the Q faithful term the coming reckoning), no doubt struck many of her viewers as another telltale realization of a prophecy. In reality, of course, it was simply another installment in the same rolling con, one that stretches far back in the tradition of American prophecy belief: foretelling, envisioning, and then stalling for the judgment day that is always right around the corner, just out of view.

As Perkins delivered her layover prophecies, she was of course back on the familiar turf of online soothsaying, as a political civilian. In November 2020, Oregon voters returned designated Q-traitor Merkley to the Senate, with a comfortable majority at the polls of nearly 57 percent. So on the fateful afternoon of January 6, Perkins was outside the Capitol looking in as a rioting crowd boasting a significant Q contingent sought to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election by staging a coup inside. You didn’t have to linger over the footage of the failed occupation for long in order to see the Q imprint. A man wearing a QAnon shirt had indeed led one of the first groups of pro-Trump forces up the marble stairs headed toward the Senate chamber. As the crowd pushed onward, a Capitol Police lieutenant shot and killed a QAnon-believing woman trying to breach the doors leading to the House floor. (Even the Capitol Police officer killed in the insurrection, Brian D. Sicknick, appeared to have followed some QAnon accounts on the right-wing social media platform Parler, according to screenshots shared by the extremism researcher Travis View.) One of the more surreal early images that made it out of the Capitol and on to social media showed a tattooed, face-painted man, crowned in animal pelts, standing on the Senate dais. He bellowed. He posed. He made great content. This eschatological emissary was already known to the clutch of reporters who follow far-right conspiracy theories: Jacob Chansley, the “Q Shaman,” who was also a fixture at one of the “Stop the Steal” rallies in Maricopa County, Arizona. As the insurrection spun toward mayhem, Jo Rae Perkins was standing outside the building, periodically streaming her exploits on Facebook Live, in a crowd clutching Trump banners. The Capitol’s stately columns and black iron lamps framed her as she posed for a selfie—near a sign reading PELOSI IS SATAN.

In the invasion of the Capitol, QAnon was both frontline and the first blood. The group wound up coming closer than anyone might have imagined to seeing its fabled storm blow through the seat of power in Washington. Before the Q faithful swarmed Congress, the prospects for a post-Trump afterlife for QAnon seemed dim, more likely to diffuse, refracting their various conspiracy theories across multiple, smaller self-organized fringe organs of conspiratorial cultural reaction.

But the events of January 6 mean that the true believers of QAnon know they are not alone now. Like the QAnon shaman, they can still look more ridiculous than menacing. But that’s also true of many terrorizing groups that come in what at first might have been, even to themselves, only a costume—from the shitposters on 4chan draped in the flags of their imaginary country, Kekistan, to the Ku Klux Klan.

Perkins told me in a January phone call that she was at the Capitol as windows were shattered, shots were fired, and people lost their lives. She said she stayed out of the fray and “didn’t see any violence.” Yet she came away with the feeling that something was wrong, spinning wild theories to me about antifa infiltration, telling me she would send me a video proving that someone in law enforcement had let the Q Shaman into the Capitol. (To date, she has not.) She was devastated by Ashli Babbitt’s death, she said. “[Who] shot and killed this woman? Were these really—I mean this is where my brain goes—were those really law enforcement officers, in that hallway, or were they people dressed to look like law enforcement officers?” (A Capitol Police chief confirmed one of the force’s employees had killed Babbitt, and that the employee was put on leave.)

The riots were a multimedia affair, an enormous text to sift through for signs of what’s to come, and—like much of the press and law enforcement—that’s what Perkins and others in the Q community have been occupied with uncovering ever since. “Why are there 30,000 troops in Washington, D.C.? Why is there barbed wire up all over around the Capitol building?” she asked. When I countered that it was in response to an unprecedented riot in which Q believers figured prominently, she interjected. “They infiltrated!” she insisted. “I’m telling you, those were antifa.”

The messages from the quasi-mythical figure of Q that had once helped drive all this on have all but dried up since Election Day. Still, QAnon followers remain invested. A common QAnon directive, “Trust the plan,” can paper over almost any loss or lie—a mantra all but customized to help the movement endure. Hillary Clinton isn’t in jail yet, but “high-profile arrests” are always coming, and the conclusive evidence is just about to drop. Trump loses an election (or, to them, appears to)—but the setback is only proof he will overcome and vanquish all traitors.

Indeed, while Trump was significant to QAnon, he may not be essential. As with what’s come to be known as Trumpism, the former president may have defined a phenomenon and claimed power within it, but that’s not because of who Trump is—it’s a reflection of what this country already was.

At its core, QAnon is powered by three overlapping elements: sex trafficking panic, apocalyptic far-right militarism, and tech monopoly. None of these are exclusively twenty-first–century phenomena. Sex trafficking panics have periodically seized the United States; since the 1890s, they have ebbed and flowed with racist and anti-immigrant ideologies. These moral panics furnished a culturally acceptable means of cloaking raw nativist and xenophobic uprisings in the mantle of protecting innocence, as they produced frightening blood libels about imperiled women and children, mostly white ones. Far-right militarism has recurring cycles of prominence, too, and however far outside the political spotlight far-right groups might be during the fallow times, they endure and adapt. The fear—or hope—that such are living through the end of the American republic (again, mostly as it appears to white people) supplies a powerful theme of grassroots organizing on the right. Today’s version of this apocalyptic dogma connects disparate extremist groups, from militias like the Oath Keepers, who see themselves as the last defense, to accelerationist groups like the Boogaloo, who want to bring on the end themselves. Tech monopoly may seem like a distinctly new phenomenon, but as with sex trafficking panics and far-right extremism, it, too, echoes earlier mass communication shifts—when new industries concentrated wealth and power in the hands of the few, and touched off fears of what future tech-driven social transformations would bring.

These three areas of concern have overlapped before: Anti–“white slavery” campaigners claimed railroads enabled the traffic in women and girls, while today’s sex trafficking panic, gripped by an outsize conception of social media stranger danger, has led Congress to regard websites as their primary battleground. And all three elements are themselves bound up in and often expressed through racist ideas and decidedly reactionary notions about gender and sex. It’s well worth recalling in this connection that one of QAnon’s most effective recruitment tools began life as a website for rating the hotness of various people (with women in mind). When it became Facebook, it was brought to unimaginable scale in part due to the support of a billionaire tech investor, Peter Thiel, who has mused that granting women the vote was on balance a bad idea for the forces of libertarian market rule—and who in more recent years broke bread with both Trump and a notable white supremacist seeking to create a “white ethnostate.”

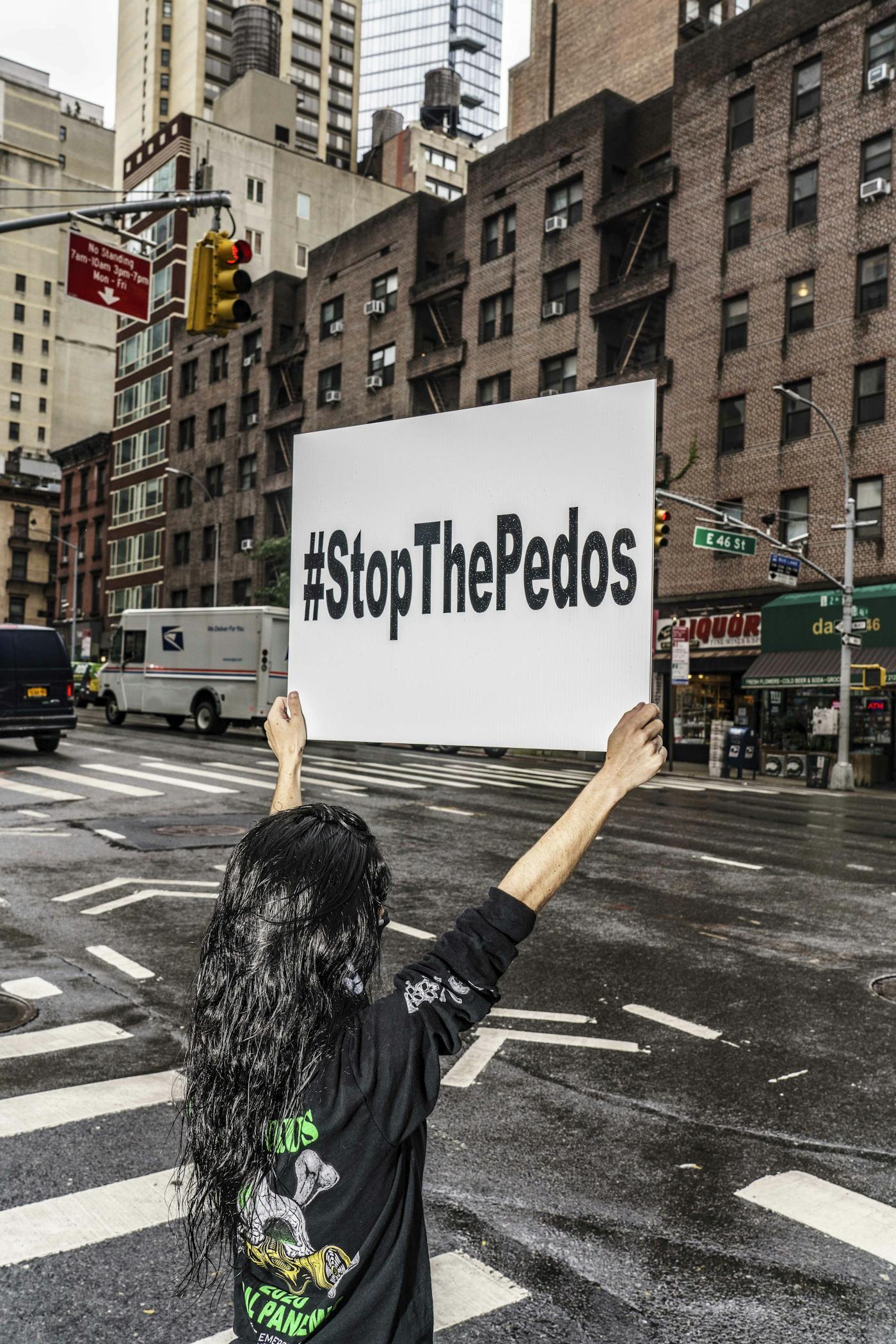

Ashli Babbitt, the woman shot and killed by a Capitol Police lieutenant as she was trying to enter the Speaker’s Lobby on January 6, still has a Twitter account online. She had posted about Pizzagate—the conspiracy theory that preceded QAnon and involved a fictitious pedophilia ring led by Hillary Clinton and other Democratic leaders. And Babbitt also waxed prophetic about QAnon: “We have to #SaveTheChildren,” she said on Twitter this June. “800k children disappear yearly.... those are the ones we know about... these ppl are sick,” and she added a throwing-up emoji. The other woman who died at the Capitol, Rosanne Boyland, came to QAnon by way of sex trafficking panic, her sister confirmed to The Associated Press. “Boyland had begun following the conspiracy theory over the past six months,” the report said, around the time that QAnon was mainstreaming on social media through the use of more gentle-sounding hashtags, like #SaveTheChildren.

Boyland was part of a vast corps of new recruits who found their way into QAnon in this manner at this time, via viral panics such as the bogus claim that the online furniture retailer Wayfair was concealing trafficked children in its product line. “The way in which people encounter, for example, QAnon now is through relatively mainstream, non-absurd topics,” Melanie Smith, who leads analysis for the online research firm Graphika, told the U.S. House Intelligence Committee during an October hearing on misinformation. “We’re seeing a huge explosion in content around child sex trafficking and child sexual exploitation through the Save the Children movement.” Smith called QAnon “the most pressing threat to trust in government, public institutions, and democratic processes.” Researchers at the Network Contagion Research Institute and the Polarization and Extremism Research Innovation Lab named sex trafficking one of the central factors in binding people to QAnon and deepening their involvement. “Legitimate concerns over child abuse and human trafficking create vulnerabilities to radicalization into the QAnon cult,” they wrote in a white paper issued last December.

When panic about sex trafficking crashes into online communities constructing “alternative facts,” the results aren’t confined to a cluster of social media profiles. Sex traffickers are identified (falsely) as the villainous cabal secretly controlling the world, so it’s no great leap for QAnon supporters to conclude that any designated villain could be a sex trafficker. This appears to be in the process of spreading even beyond the far-right convergence with the Trump establishment that was on display at the Capitol. Two days after QAnon supporters forced their way into the Capitol and Babbitt and Boyland died there, Senator Lindsey Graham was surrounded by protesters at Reagan National Airport, who said they were streaming the confrontation. Graham had voted against the efforts to stop the electoral vote count. “Lindsey, you’re live on YouTube right now,” said a man standing opposite him at the gate. “Can you make a statement to the American people?... Nobody’s going to hurt you.” When the senator did not and began walking away, flanked by security, protesters followed him, yelling, “Traitor!” What sounded like a woman’s voice can be heard over the rest, as the senator’s guards escorted him toward safer terrain: “Sex trafficker! Sex trafficker! You’re a sex trafficker!”

More than a decade ago, the Department of Homeland Security knew that the ability of far-right groups to organize online was “potentially making extremist individuals and groups more dangerous and the consequences of their violence more severe.” This was the finding of a 2009 paper by Daryl Johnson, an analyst at DHS at the time. Johnson anatomized the threat posed by right-wing extremist violence, and concluded that “white supremacist lone wolves pose the most significant domestic terrorist threat because of their low profile and autonomy—separate from any formalized group—which hampers warning efforts.” Another key strain of extremist organizing on the right, Johnson found, was rooted in the racist responses to the election of the first Black president. When the paper was leaked, a slew of political leaders on the right claimed the Obama administration was singling them out, and, in the ensuing media uproar, DHS repudiated Johnson’s paper. In 2010, Johnson says DHS disbanded his team. “This is what happens,” Johnson told Time after the January Capitol riots, “when you neglect a threat and let it grow year after year, plot after plot, attack after attack.”

The unchecked growth of far-right conspiracy-mongering online also meant that, in terms of messaging, the movement was poised to enter prime time. Many of today’s lead organizers are doing their networking and recruiting out in the light of day, with the assistance of a wide array of celebrity enablers, from Alex Jones and Roseanne Barr to former President Trump himself. Ardent fans of The Turner Diaries don’t need to wait for the gun shows that the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh frequented to find one another. But about one month before that 1995 bombing, Stormfront became one of the first white nationalist forums to launch its own website. When the man who headed to El Paso in 2019 to shoot and kill 23 people and injure two dozen others wanted to release his white supremacist manifesto timed to the attack, he made a post on the message board 8chan—a platform where Q left his “drops” for followers to decipher—19 minutes before the first 911 call. And while online visibility might forewarn surveilling authorities about Q-related insurrectionist plans, it has not stopped the violence, as the January rioting at the Capitol made all too clear. An FBI intelligence bulletin from the agency’s Phoenix field office considered “conspiracy theory–driven domestic extremists” a domestic terror threat as early as May 2019, and referenced QAnon. Days after the January 6 riot, Avril Haines, President Biden’s director of national intelligence, announced plans to work with DHS and the FBI to assess the threat QAnon may pose.

Even before graduating to the status of domestic terror threat, QAnon has played a role in alleged crimes involving “rescues” of children. In at least four separate incidents over the last two years, as the website Right Wing Watch and reporters like Will Sommer at The Daily Beast have tracked, QAnon followers are alleged to have kidnapped children in order to protect them from figures whom they had designated as pedophiles, sexual abusers, or sex traffickers. (In a fifth incident, a Texas woman said she was running down a driver who, according to an arrest affidavit, she said “had kidnapped a girl for human trafficking,” when she allegedly drove her car into two other vehicles, one carrying a mother and her minor child.)

But for all the lurid press attention the Q movement has won, it is too simple to say people like these were motivated only by a conspiracy theory they discovered online sometime in the last three years. It is more likely that QAnon provided a framework for at least some of them to connect whatever day-to-day life struggles they were facing with something bigger. A mother in Utah—charged with kidnapping her son while she had him on a custodial visit, after accusing her estranged husband of abusing the child—had shared a QAnon conspiracy theory on her Facebook page about Child Protective Services being a front for child trafficking. Under that more spectacular claim, though, was the conviction that the child welfare system was endangering children by keeping them with abusive parents and denying custody to those—presumably like her—who wanted to protect them. “Call the Trump Human Trafficking Task Force!” she wrote in March. “The neighbors being punished for protecting the babies need you!! Drain the pedophile swamp! Learn the signs!!!” After her arrest in October, she wrote on Facebook. “Thank u beautiful people, we r all truly in this spiritual war together fulfilling our roles.”

In line with these visions of a far-reaching state effort to undermine the true guardians of the nation’s children, QAnon has its own sexual politics: Good mothers must always be on alert to protect their children from the imagined forces of sex traffickers and pedophiles, even if that means taking criminal or violent actions to rescue the children or attack the presumed perpetrators. In November, a Kentucky mother who allegedly kidnapped her twin daughters was arrested in Georgia on second-degree murder charges, the only named suspect in the shooting death of the man whose QAnon-influenced legal theories reportedly influenced her efforts to kidnap the children. Now, according to a witness, she believed he was part of the plot to keep her children from her, too. This militant brand of self-styled child protection is not something that will be dispelled by Facebook or other social media platforms banning QAnon accounts. It has roots, too, in something that precedes the first Q posts, the Pizzagate furor, and Trump’s alleged interest in saving “the children”—the call to combat the shadowy forces of global sex trafficking.

The first time I spoke to anyone about their righteous feelings concerning children trafficked for sex—feelings so powerful that they would take it upon themselves to investigate the allegedly booming trafficking empire—was in the private dining room of a restaurant in Lower Manhattan in the summer of 2015. Radd Berrett, the man telling me of an elaborate mission of child rescue—going undercover to produce video evidence of child sex-trafficking rings, putting himself and his fellow operators in harm’s way to get “the bad guys”—was with a group called Operation Underground Railroad (OUR). He placed his hand on my leg. He was expressing remorse to me: that the children didn’t know, when he posed as a pedophile to get the “evidence,” that he wasn’t really there to hurt them. This was all part of an OUR press junket.

Today, the group has raised millions of dollars from online supporters seeking to finance these targeted tactical “operations.” (A press representative for the group declined multiple requests to speak on the record.) Its founder and president, Timothy Ballard, is a Mormon, whose appearances on fellow Mormon Glenn Beck’s show yielded audience donations to OUR of $300,000 in a single day back in 2013. Beck, no stranger to conspiracy theories himself, positioned Ballard as a tough guy in tactical gear, facing down dangers and ready to do what the government can’t—or won’t—do to save imperiled children from sex traffickers. OUR’s militarized approach, combined with its ability to turn popular interest in sex trafficking into fundraising success through social media, places the group in the same uncomfortable position as other anti–sex trafficking organizations that engage in dramatic stings and rescues: They now share some resemblance to the vigilante actions of Pizzagate and QAnon adherents. The Arkansas man who was photographed with his feet up on House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s desk on January 6, reporters learned, recently helped bring in $1,000 for OUR at a fundraiser, where he and the others at the event posed with guns alongside a sign reading DEAD PEDOPHILES DON’T REOFFEND. (He has since been arrested.) And OUR has even taken Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes along on a “rescue.”

The ties OUR has made with state officialdom, particularly law enforcement agencies, may prove its undoing. A Vice World News investigation and a New York Times Magazine story have raised questions about the nature of OUR’s collaborations with law enforcement units working on the sexual exploitation of children. The group has highlighted these joint undertakings in promotional literature, but they appear, at times, to have been overstated, the Times and Vice reports both found. OUR is now the subject of a criminal investigation on yet-to-be-specified charges in Davis County, Utah. Fox13 Salt Lake City reported that, “in recent posts to his Instagram account, [Davis County District Attorney Troy] Rawlings implied a local nonprofit was conducting illegal fundraising efforts by taking credit for arrests made by the Davis County Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force.”

Though OUR is very much steeped in the same culture of moral panic that’s given rise to QAnon, the group continues to enjoy a comparatively respectable and legitimate public image. In 2019, “Operation Underground Railroad Inc.” brought in more than $22 million. That same year, Ballard was serving as a White House anti-trafficking adviser appointed by Trump. Over the summer of 2020, as QAnon began to make more headway into the media mainstream, Ballard tested some new messaging. As the Wayfair panic took hold, Ballard made his own video, taking care to refrain from overtly endorsing the conspiracy theory, but pivoting from its sensational claims to promote OUR’s cause. “No question about it,” said Ballard, “children are sold on social media platforms, on websites, and so forth. So I’m glad people are waking up to it, especially right now.” QAnon supporters turned up in the comments section, hearing Ballard’s testimony as confirmation of their belief system. Then, as QAnon hit the streets to #SaveTheChildren, as Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins at NBC News have reported, in more than 200 rallies and marches, OUR organized its own rallies. At both the QAnon and OUR rallies, supporters held signs that carried a message equally at home in either group, or anywhere else, for that matter: Children are “not for sale.” Facebook being Facebook, the image of both groups converged further there: QAnon supporters’ content was just a click or two from kindred material promoted by OUR.

In the wake of this convergence and some of the critical reporting it attracted, OUR and its allies tried to put some clear distance between themselves and QAnon. Utah Attorney General Reyes postponed an August anti–sex trafficking rally once his office received questions about the event’s links to QAnon. He clarified on Twitter, “This event is separate and NOT related to the Save the Children group. It is with Freedom for the Children.” Yet, according to Zadrozny and Collins at NBC News, Freedom for the Children was behind more than 60 such rallies, and its co-founders’ personal Facebook profiles included posts playing up Pizzagate.

OUR still claims it has nothing to do with groups like QAnon. “To be clear, Operation Underground Railroad (O.U.R.) does not condone conspiracy theories and is not affiliated with any conspiracy theory group in any way, shape, or form,” reads a statement posted to the group’s website in September 2020. Yet OUR and its supporters now sit alongside QAnon, in a convergence of sex trafficking panic, right-wing militarism, and social media mythmaking—a fungible alliance that will likely outlast QAnon itself.

Members of one such organization, called the Covenant Rescue Group, roll out in a vehicle they have promoted online as the #boogaloomobile. The Boogaloo are the overtly violent, “extremely online” group that also stormed into the Trump-enabling vanguard of the hard right in 2020. “The mission of Covenant Rescue Group is to make sure those on the front lines in the fight against human trafficking are equipped to do their job,” reads an August Facebook post from the group. “Always sharpening the tip of the spear.” That month, the group was in Genesee County, Michigan, and reportedly assisted in an operation with the sheriff’s office to “rescue” youth from sex trafficking. On its own Facebook page in August, CRG shared a photo of a pickup truck with an RV attached, commenting, “Bad guys don’t know what’s coming...... #boogaloomobile #readytoroll.” The photo, posted by The Shooting Institute, was captioned with coronavirus denialism and featured anti–sex trafficking hashtags. “With everyone freaking out about this overrated Chinese Virus we decided to stay away from hotels.” They were “[l]ooking forward to linking up soon” with “@covenantrescuegroup to help fight human trafficking.”

Covenant Rescue Group was founded by Jared Hudson, a former Navy SEAL, according to a Michigan NBC affiliate’s story. Hudson is also, according to a story on the website of the Air Education and Training Command (part of the U.S. Air Force), the CEO of TSI, “a company made up of former Navy SEALs, special operations, and law enforcement individuals that travels around providing expert level firearms and tactical training.” Both groups were in Genesee County assisting local police.

Genesee County Sheriff Chris Swanson started his own rescue operation after going on one with OUR, he said when reached by phone. His first operation was around five years ago, and his second was in Haiti. “That’s where I met Jared Hudson, who was instrumental in forming Covenant Rescue Group.” (Ballard has said that OUR has been “in the field” with Swanson; he called him a “true brother” in June.) Swanson called his domestic version of OUR the Genesee Human Oppression Strike Team (or GHOST), and it launched publicly in 2019. The following summer, he said, Covenant Rescue Group asked to go on a GHOST operation. “They said, ‘Hey we’d like to partner with you and we’d like to take a model and see what you’re doing to roll it to other places.’” The Shooting Institute was involved, too. “I’m not sure how to respond to the conspiracy theory stuff, but who cares?” Hudson told TNR. He said that TSI’s operations “in no way are apart [sic] of or support any extremist groups” and are motivated only to “share Christ and help the innocent.” Swanson explained that, for the operation in August, the institute’s staff “did the firearms training during the day, and then they did a night of operations with us and GHOST.”

Both groups later featured videos made on these operations: men in tactical gear pushing a man down to the floor in a hotel hallway. The videos are meant, as OUR’s are, to attract donations and build influence. Dave Lopez, whose personal Facebook page identifies him as the director of operations at CRG, promotes CRG operations on his own page alongside posts denying the severity of the Covid crisis and touting bogus election-fraud claims. Swanson said he hadn’t seen the #boogaloomobile, either the actual vehicle or the Facebook posts. “That’s the first I’ve heard of that.” Swanson said he had concerns about the other posts described by TNR, and that he would be tabling further collaborations with the groups.

Radd Berrett is no longer with OUR, he told me when we spoke by phone in January. “I’ll never get to see those kids,” he said, repeating the story he shared in 2015. “The last time those children looked at me, they thought I was there to rape them.” He was also sick, he said, about the story I was going to write. “It’s not something I want written about. I don’t want, ‘This guy reached out and grabbed my leg as he was telling me these horrible things.’ But if that happened, that happened. I don’t remember. I can tell you, that is disgusting to me.” But before he told me, “I’m beyond sorry,” we talked about Dave Lopez, whom he knew from his OUR days. Did it sound odd to him, I asked, that Lopez was sharing these conspiracy theories? “If he’s doing it,” Berrett replied, “there isn’t a ... doubt in my mind that that’s what he believes.” He reflected a bit more, and then added, “I would go anywhere in the world to rescue a child with Dave Lopez because he is that good at it.”

The #boogaloomobile was not a one-off; the TSI Facebook account also tagged a concealed-carry holster it recommended as #boogaloo gear. (“To clear up the boogaloo mobile,” wrote CRG president Josh Moody in a statement, “that’s an ongoing joke we (the men who serve with CRG) use when things are about to get amazing ... which they did on that op, by the way.”) One post features the hashtag #killpedos, and a photo of a man in tactical gear. Three days after the Capitol riots, the page featured a meme updating the famed Martin Niemöller poem about the rise of Nazism: “Then they came for the conspiracy theorists.…”

Right-wing rallies against coronavirus restrictions are what brought QAnon and Boogaloo followers under the same tent. Leah Sottile, a journalist who has extensively reported on far-right extremist groups, observed at one such rally in May that they are de facto revival gatherings “where everyday people” can “be reborn.” At such movement-driven altar calls, initiates to the saving truths concealed by the sinister conspiracies of global child endangerment can be seen alongside the Boogaloo, beside the militias, “leaving their world behind and subscribing to a new collective truth. This is where they find fellowship with other people who are upset enough about the same things, who hold the same fears and frustrations. This is where isolation ends, where communion begins.”

The first time I felt a large crowd rally like that was back in 2012, at a three-day crypto-revival organized by Glenn Beck, staged in July in Arlington, Texas, first at a megachurch and then at Cowboys (now AT&T) Stadium. It was called “Restoring Love.” On the final night, a kind of Tea Party tailgate atmosphere prevailed. I talked to a youngish guy who told me he and his father came all the way there in their RV from Alberta, Canada. I asked what inspired that kind of pilgrimage. Two things, his father said: “the socialist movement” and “the abortion.” They had a book with them that they let me look at while we talked, The Covenant, One Nation Under God. It was by a Glenn Beck–approved author I hadn’t heard of, named Timothy Ballard, the future founder of OUR.

On the same fiery pavement, I met my first Ted Cruz fans. Mitt Romney may have been running for president, but I heard almost nothing about him (and a vendor told my boyfriend he shouldn’t have even bothered bringing the Romney 2012 shirts sitting untouched on his merch table). What I heard about was the apocalypse President Barack Obama’s existence portended. People were hoarding guns and gold—nothing new in the far-right end times world, but new to me, and a bit jarring to hear this discussed openly, feet from the nacho stand.

The apocalypse has been on its way forever. If Trump leaving the White House is supposed to be another sign, it is just one among thousands. And he doesn’t seem to be moving out of the ambit of the QAnon world at all, but rather has assumed the function of their noble, fallen king. In the closing days of his administration, he had fully aligned himself in the increasingly baroque and hopeless conspiracy theories that QAnon followers helped create. So had his Hail Mary legal team, Sidney Powell and Lin Wood, who, like the president (and thousands of QAnon followers), had their biggest mouthpiece, their Twitter accounts, permanently suspended after the riots he helped instigate. And it seems a safe bet that Representatives Greene and Owens are but the founding members of a prospective House QAnon caucus; there are already two more Q-aligned House candidates running in 2022.

Trump did not merely amplify and empower QAnon, it turned out; Q believers had amplified and empowered him. They rallied people against the “stolen” election, against pandemic restrictions, against fantasies of sex trafficking cabals. Q himself—the pseudonymous, dubiously real highly placed government official at the center of the movement’s unhinged speculations—may have all but stopped making “drops” now, but it doesn’t matter: QAnon is self-sustaining. If the true believers don’t need Q, they don’t need Trump. So while many Americans were shocked to see the image of the shirtless, horned, and fur-clad QAnon shaman at the dais of the U.S. Senate on January 6, his presence there was nothing new. That was just the day when we were forced to see him.