After a year of mounting pressure from investors and outside critics, Leon Black, the billionaire chief executive of private equity giant Apollo Global Management, announced on Monday that he would step down later this year. Apparently the revelation that Black gave $158 million to deceased sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein for supposed financial advice was enough to provoke an internal revolt among Apollo’s leadership. According to The New York Times, which previously dubbed Black “the billionaire who stood by Jeffrey Epstein,” a fellow Apollo co-founder wanted Black to step down immediately. Black refused but later agreed to relinquish the CEO seat while remaining chairman of the company’s board. He set his departure date as sometime before July 31, when he turns 70. And in a typical gesture of billionaire contrition for an association he insists was honorable, he’ll donate $200 million to “women’s initiatives,” according to The Wall Street Journal.

Leon Black’s not-quite fall from grace is emblematic of what passes for elite accountability in this country. Leaving on his own terms, his fortune intact, relatively untouched by legal concerns, still wielding the chairmanship of the firm he founded—things could hardly be better for a man who maintained a close financial relationship, if not more, with a convicted pedophile. He may lose a few social invitations, perhaps have his name taken off a building he donated to some nonprofit institution, but Leon Black will be just fine. He now belongs in the busy pantheon of American elites who suffered no real consequences for their alleged crimes or disturbing associations. (It goes almost unsaid that Black’s own business history as a vulture capitalist and owner of Constellis, a private military company descended from Blackwater, also deserves scrutiny that will never come.)

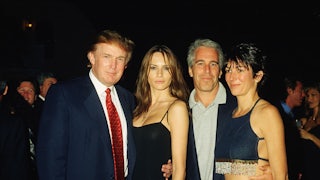

What exactly did Black get from Jeffrey Epstein? According to the investigation by law firm Dechert LLP, Black “believed, and witnesses generally agreed, that Epstein provided advice that conferred more than $1 billion and as much as $2 billion or more” in tax benefits, the Journal reported. It’s hard to believe, even if you haven’t followed the Epstein saga, that one person’s financial advice could be worth so much. And yet this is the story told by other billionaires, such as Les Wexner, who gave Epstein control over his entire fortune and gifted him the most expensive house in Manhattan; or Bill Gates, for whom Epstein consulted on charitable contributions. Somehow Epstein, whom some victims said they never saw work, was capable of giving preternaturally good, spectacularly valuable financial advice that, in turn, earned him enough money to finance decades of sexual violence. But of course, Epstein’s friends and clients were ignorant—shocked, absolutely shocked—about the dark underbelly of his lifestyle.

What’s especially galling is that we’re supposed to believe this narrative: that Epstein was both a financial savant and perfectly capable of hiding his heinous (and daily) crimes from the many rich and famous people he knew. The investigation into Leon Black’s association with Epstein was conducted by the kind of large, prestigious firm that specializes in whitewashing allegations against famous men. Time and again, in universities, publicly traded companies, arts institutions, government agencies, and elsewhere, we have seen the same pattern play out. A law firm or investigator is brought in, and a few months later a report appears that acknowledges some lapse in judgment but never—ever—anything deserving termination, much less prosecution. In connection to Epstein, Harvard and the MIT Media Lab have followed basically this playbook.

Black’s story is similar to that of former President Bill Clinton, another friend of Epstein whose history of rape allegations and rumored relationship with Epstein madame Ghislaine Maxwell have only slightly diminished his public reputation. At President Joe Biden’s inauguration, Clinton mingled comfortably with former President George W. Bush, whose résumé of war crimes and public deceptions hardly needs reciting, and with former President Barack Obama, who expanded the drone program, assassinated American citizens, and contributed to the devastation of Libya and Yemen, among other military feats. Clinton and Bush, in particular, were well on their way to reputational rehabilitation before Donald Trump’s murderous presidency. Now they can bask in the adulation of a relieved public that either doesn’t remember their crimes or doesn’t care.

Elite impunity may be one of the defining features of America’s tilt toward oligarchy. The list of recent examples is practically endless: a lack of prosecutions for the 2008 financial crisis or any crimes of the Bush years; Donald Trump’s numerous unpunished lies and crimes; the refusal to censure or expel Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz, or any other politician who supported the Capitol riot; Trump’s children walking away from the administration’s wreckage more powerful than they were four years ago; the habitual exoneration of powerful men accused of sexual harassment or assault. We have become inured to the blaring irony of, say, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo writing a book on excellence in governance while overseeing thousands of deaths, followed by a botched vaccine rollout.

The ultrarich and the ultrapowerful are different from you and me. They get away with things we might never imagine. Most Americans can only watch as reputations are laundered, crimes erased or denied in a haze of legalese, victims quietly paid off, the whole mess dismissed as the poor judgment of a man guilty only of being too trusting. The dissonance between this narrative and the obvious, but perhaps legally unprovable, truth should ring loudly in the public mind. Maybe, with enough of these examples of egregious injustice, the demands for accountability for people like Leon Black might start to matter. But not yet.