This we know: On August 10, 2019, Jeffrey Epstein, a prolific pedophile and the most high-profile prisoner in America, died early in the morning in his prison cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in downtown Manhattan. His death was described in official reports as a suicide, the first to occur in decades at the MCC, where conditions could best be described as squalid.

Practically the rest of the Epstein story remains in dispute, though some impressive investigative reporting and courageous victim testimony have brought much-needed clarity. With seemingly endless cash and connections, Epstein had spent decades abusing young girls with impunity, save for a sweetheart plea deal his lawyers secretly negotiated with the federal government in 2007. Without Julie K. Brown’s reporting in the Miami Herald, published in 2018 as a series called “Perversion of Justice,” Epstein might never have been arrested, for the final time, at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey on July 6, 2019.

The year since Epstein’s arrest has spawned a raft of reportage, podcasts, feverish Reddit threads, books, and documentaries. Recent entries include Netflix’s Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, produced by James Patterson, who previously wrote a book about Epstein, and A Convenient Death: The Mysterious Demise of Jeffrey Epstein, an investigatory book by the journalists Alana Goodman and Daniel Halper.

The Netflix special, spread over four episodes, contains painfully revealing interviews with some of Epstein’s many victims. But there’s an obvious conflict of interest at the heart of the project: Patterson, who has a house in the exceedingly wealthy town of Palm Beach, Florida, as did Epstein, is a friend and literary collaborator of Bill Clinton, who for a time was a friend and traveling companion of Epstein. In a two-year period, Clinton flew on Epstein’s jet, nicknamed the Lolita Express, 26 times. The connection raises the question of whether the Netflix documentary, while valuable for its centering of victim testimony, is a whitewashing of the upper-crust social milieu that protected the millionaire pedophile and allegedly partook in his human-trafficking ring, which furnished hundreds, or even thousands, of teenage girls for the enjoyment of Epstein and his associates.

With a few exceptions, A Convenient Death is about as up to the moment as the sluggish book-publishing industry might allow. A product of two conservative journalists, it’s not shy about indicting the liberal media’s complicity when it comes to burnishing the Epstein myth (he’s a demon now, but for years publications like New York magazine reported on Epstein as a mysterious financial savant). It also considers Bill Clinton’s close association with Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell, who played the roles of Epstein’s sexual partner, madam, and fixer. According to the authors, Maxwell likely carried on a sexual relationship with Bill Clinton in the early 2000s. She also became close friends with Chelsea Clinton. In 2009, Maxwell, whose current whereabouts are unknown, was served a subpoena in an Epstein-related lawsuit while attending a Clinton Global Initiative conference devoted to human trafficking, a subject she likely knew much about. That embarrassment didn’t stop her from attending Chelsea Clinton’s wedding the next year, nor from attending later CGI events.

Still, despite casting an accusing glance at Clinton, A Convenient Death fails to consider the full scope of Epstein’s crimes and his alleged accomplices, some of whom are mentioned only in passing in the Netflix special. Taken together, the documentary series and the book tell us more about who Epstein was and his diabolical crimes, but they only gesture at the powerful networks of money, political power, and social privilege that helped sustain Epstein’s world.

The numerous inconsistencies and lacunae surrounding Jeffrey Epstein’s death could fill its own book—there’s another documentary series available online about that subject—and a lot of powerful people had reason to want him dead. Epstein was friends with presidents, princes, billionaires, and famous scientists, lawyers, and journalists, and he sometimes told others that he had dirt on these people.

All of his houses were reportedly wired for surveillance. Two of his victims recall being shown a kind of security room with banks of monitors showing live feeds from throughout Epstein’s mansion. (Over many years, Epstein received at least three “massages” a day from girls, who were often lured with the promise that they would receive $200 for performing a massage. Invariably, Epstein turned the massages into assaults. The girls were then offered more money if they brought in a friend to replace them.) Friends recount being toured through rooms and having cameras pointed out to them. “This was a blackmail scheme,” says Virginia Roberts Giuffre, one of Epstein’s victims, in Filthy Rich.

Where this blackmail material is now is one of the many unknowns of the Epstein case, though the FBI is reported to have recovered nude photographs, many of them of underage girls and some possibly of male Epstein associates, when it raided Epstein’s Manhattan home.

There’s some crude psychologizing in A Convenient Death. To say that Epstein had “contempt for women,” as one friend suggests, citing Epstein’s high school nebbishness, seems obvious enough. The authors speculate that Epstein might have been gay—he had a rumored relationship with the retail magnate Les Wexner in the 1980s, and some in Wexner’s circle called Epstein “the boyfriend.” During one deposition, which appears in the documentary, Epstein was asked if he was bisexual. He balked at the question.

The founder and former chairman of L Brands, which includes stores like The Limited and Victoria’s Secret, Wexner was Epstein’s longtime friend and key enabler. A serial liar and cunning manipulator, Epstein sometimes approached women claiming to be a talent scout for Victoria’s Secret. He said he was a money manager for billionaires, but Wexner was his only confirmed client. After meeting Epstein in the mid-1980s, Wexner eventually gave him power of attorney, allowing him full control over Wexner’s billions. The source of most of Epstein’s own fortune, estimated at nearly $600 million at the time of his death, remains mostly unknown, but much of it appears to have come from Wexner himself, including mansions in Ohio and New York that Wexner essentially gifted to Epstein. According to transaction records, it appears that Epstein also used his position as Wexner’s fiduciary to off-load huge chunks of Wexner-owned stock, while skimming millions for himself. (Wexner eventually disavowed Epstein, claiming he stole $46 million from him—a relatively small amount compared to the overall sum Epstein likely earned through the relationship.)

Epstein’s associations extended widely, and friends gave liberally, both to Epstein’s charities and his pet causes at Harvard and MIT. Leon Black, the chairman of Apollo Capital, gave Epstein $10 million. Bill Gates, who called Epstein’s lifestyle “kind of intriguing,” allegedly gave the MIT Media Lab $2 million at Epstein’s direction.

The list of eminences who dined with Epstein, flew on his plane, went to his island, and stayed at his mansions is an absurd compendium of the rich and powerful. (Here’s Epstein’s little black book, published by Gawker in 2015.) Some have been accused by name of abusing and raping girls procured by Epstein’s operation. Nearly all of these people—among the most well-resourced people on the planet—claim innocence and ignorance. They simply had no idea that they were associating with perhaps the most prolific sex trafficker of our time. The mysterious flows of money, houses filled with surveillance equipment, walls adorned with photos of underage girls, massage tables in every room, young girls constantly coming and going—everyone looked the other way.

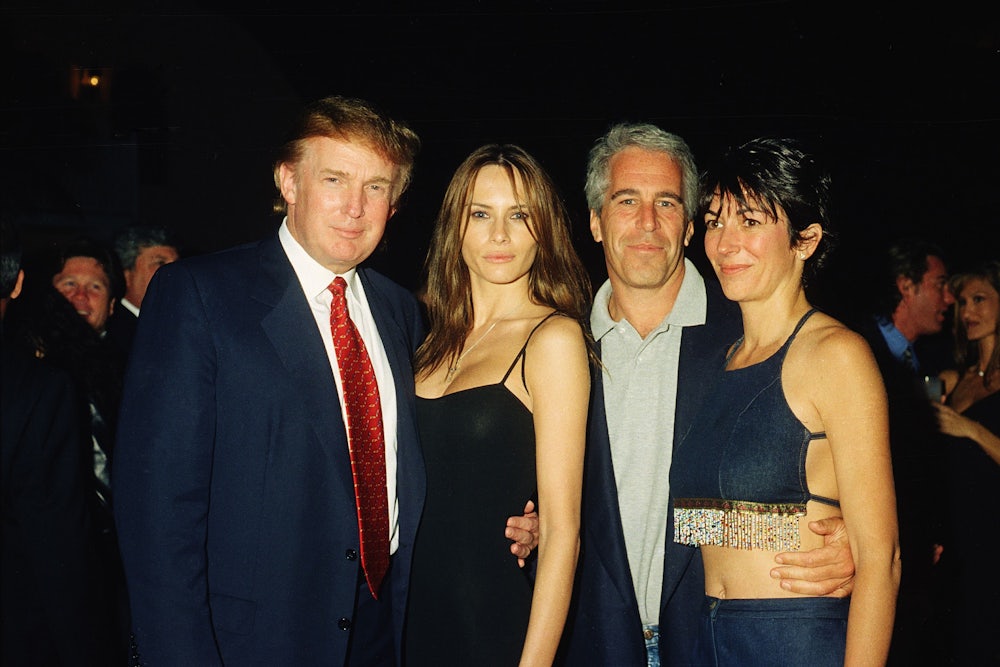

Law enforcement has its own failures to account for here. Someone tipped off Epstein when his Palm Beach mansion was going to be raided by police, and computer hard drives subsequently disappeared. Alex Acosta, who was later appointed labor secretary by Epstein’s onetime friend Donald Trump, bears responsibility for cutting the unprecedentedly lenient plea deal in 2007 that not only immunized Epstein against further prosecution but also covered all of his co-conspirators—named and unnamed—for any crimes committed in the past or even in the future. It was a stunning giveaway, one that broke the hearts of victims and their advocates. Acosta later explained, in a remark that he might regret, that he was told that Epstein “belonged to intelligence.”

That brings us to the ultimate question hovering over the Epstein saga, one that’s difficult to address because it bleeds so easily into the conspiratorial: What was it all for? Victim testimony describes the Epstein trafficking network as being much more than a vehicle for one man’s perverse sexual enjoyment. Many others partook. The stench of blackmail hangs over the whole enterprise. Alex Acosta seemed to believe that Epstein, who had foreign passports under different names and was friends with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, worked for an intelligence agency. Ghislaine Maxwell’s father, Robert Maxwell, was widely believed to be an Israeli spy. Even Epstein’s first job as a teacher at the prestigious Dalton School—which allowed him to make the connections to transition into banking—was facilitated by Donald Barr, a former Office of Strategic Services officer and father of current Attorney General William Barr. (These connections make it less surprising that Barr has slow-played the investigation into Epstein’s death and issued contradictory statements about seeing video—now claimed to be lost—from outside the cell where Epstein died.)

As it is, Epstein’s larger circle of collaborators remains either unknown, unrepentant, or unpunished. Along with Maxwell, Filthy Rich names three other women who helped procure girls for Epstein’s “sexual molestation pyramid scheme”; none of them have been arrested. Notable associates like Jean Luc Brunel, a French model scout and multiply accused rapist, have disappeared. Maxwell somehow is still on the lam. None of the numerous people on the Epstein payroll seem to have been charged with a crime. And while The New York Times has reported on Epstein’s supposedly more legitimate businesses—ventures in data mining, genetic research, and finance, scattered from New Mexico to the Virgin Islands—no one has emerged to claim they ever worked at these places.

“We don’t need to know what happened to know we’ve probably been lied to,” Goodman and Halper write. But from where will the truth emerge, and who is qualified to tell it? Perhaps a dogged reporter like Julie Brown will write the definitive Epstein book, but for now, observers are left to piece together disparate sources and to occasionally indulge in wild speculation. As Goodman and Halper put it, “Who would you believe to tell you what happened? The elite, the press, our political leaders, or law enforcement? These are the institutions every American has been told since childhood [to trust].… But these are the very same institutions that shielded Jeffrey Epstein for years.”

They’re right. The Epstein story is in many ways representative of the larger institutional rot that afflicts our politics. It’s about different rules for the rich, governmental incompetence, and outright corruption. It’s about decadent elites operating an enormous criminal enterprise with impunity, trading money, bodies, and influence at will, with no concern for who they hurt. Alan Dershowitz—Epstein’s former lawyer and friend, who seems to accept every interview request he receives, despite the fact that he has also been accused of rape by one of Epstein’s victims—told the authors of A Convenient Death that Epstein went to his death believing himself innocent, without regrets. That’s one more reason to think that Epstein didn’t kill himself and to remind ourselves that, whatever kind of monster Epstein was, he wasn’t alone.