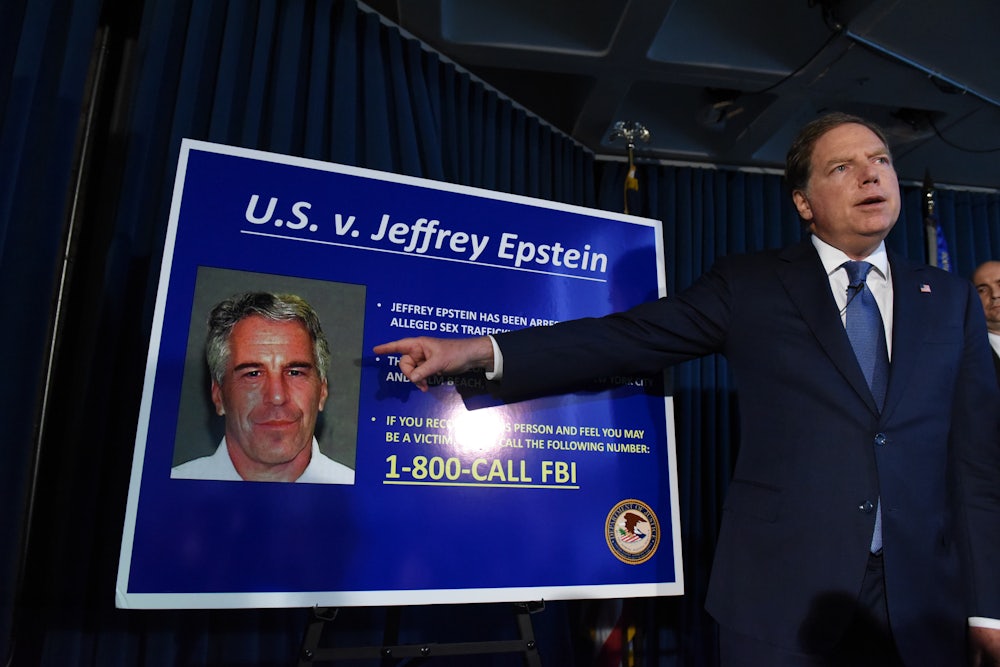

Just over one month after he was arrested in New Jersey on sex trafficking charges, Jeffrey Epstein is dead by apparent suicide. His body was removed from the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan on Saturday morning, and the void of reliable information about what exactly transpired inside the “high-rise hell” of MCC was soon flooded with conspiracy theories—none worth amplifying, as the president has done. For many responding to this news, even some seasoned journalists and politicians, it was far easier to believe that Epstein’s death could only have resulted from sinister circumstances than to confront the simple truth that jails and prisons in the United States produce death all the time.

The Special Housing Unit, where Epstein spent weeks awaiting trial, is federal prisons’ terminology for what most people know as solitary confinement. As it was described by Brooklyn College professor Jeanne Theoharis, who has written extensively on the conditions in “filthy, freezing” MCC, people are held in “isolation so extreme that you’re punished for speaking through the walls,” and under “secrecy so deep that people are force-fed and lawyers can be punished for describing the conditions their clients are experiencing.” This is the system that was meant to bring justice to the young women and girls who say Epstein abused and raped them with impunity.

In the wake of Epstein’s death, criminal justice reform experts have noted such maltreatment is routine in American jails and prisons, as numerous past cases have shown. Kalief Browder, a young black man, spent three years locked away in New York City’s notorious jail on Rikers Island simply because he could not afford bail, attempted suicide numerous times in solitary, and died by suicide after he was released. Suicide is not the whole story of jail deaths. Layleen Polanco, a young trans Latina, died from an epileptic seizure at Rikers in June. It was the ninth day of her 20-day sentence to solitary, a punishment on top of her incarceration, while she held on $500 bail.

The criminal justice system that grinds on after the deaths of young people of color is the same one in which the white and purportedly wealthy Epstein perished. But it would be a mistake to consider such deaths evidence of “serious irregularities,” as Attorney General William Barr said on Monday. It would be at best incomplete to propose that these problems could be repaired with more guards, or fewer overtime hours, or creating some kinder version of solitary confinement. Jail deaths aren’t evidence of dysfunction. They’re a consequence of a U.S. justice system that’s more capable of meting out punishment than pursuing accountability.

Back in 2007, while the FBI kicked off a national, multiyear operation searching for sex trafficking rings on websites and street corners, a federal prosecutor named Alexander Acosta was cutting a plea deal with Epstein’s attorneys. This kept Epstein out of federal prison, and according to the Miami Herald, it “essentially shut down an ongoing FBI probe into whether there were more victims and other powerful people who took part in Epstein’s sex crimes…. Federal prosecutors, including Acosta, not only broke the law, the women contend in court documents, but they conspired with Epstein and his lawyers to circumvent public scrutiny and deceive his victims in violation of the Crime Victims’ Rights Act.”

Acosta went on to become Trump’s secretary of labor, which, along with the Department of Justice, is responsible for getting justice for victims of trafficking, with an emphasis on prosecuting their alleged traffickers. He sought to slash anti-trafficking funding, which he defended by referring to the grants as going “to foreign countries for foreign country labor-related work,” and he further restricted the special visas permitting immigrant victims to remain in the U.S. to testify against their alleged traffickers. It was only after Epstein was arrested in July that Acosta stepped down from his cabinet position.

What all this evidence demonstrates, if anything, is that justice cannot be measured in successful prosecutions. Yet the prosecutions in this case will likely go on, with a focus on Epstein’s alleged co-conspirators, perhaps including the men of wealth and influence who looked the other way for years. They might also hone in on Ghislaine Maxwell, a woman who played multiple roles in Epstein’s life: girlfriend, assistant, and allegedly, procurer.

Some say Epstein evaded justice a final time on Saturday. But his death won’t stop those who say he harmed them from appealing to a system that has repeatedly failed them. They will do this in the absence of a more viable option. They will do this even knowing that there may not be much justice to be found. But Epstein has no power to determine the end of their pursuit.