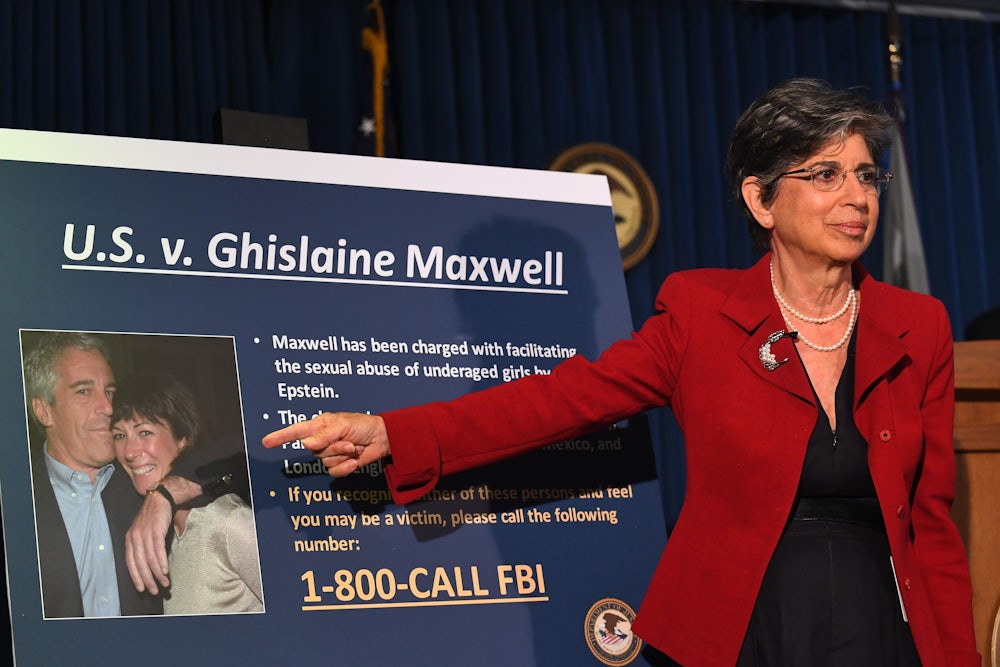

Ghislaine Maxwell, the accused conspirator in the sexual abuse of minors with the deceased Jeffrey Epstein, was transferred to federal detention this week. She will face a bail hearing early next week, almost exactly a year since Epstein was similarly charged. Last July, when the Justice Department announced it was prosecuting Epstein for the sex trafficking of minors, Maxwell was still free—though it was presumed she, too, would soon officially be drawn into the case, as some of Epstein’s victims had described her role in facilitating his alleged abuse. The Justice Department dropped its prosecution of Epstein almost 15 years ago. Now it is tasked with prosecuting Maxwell and, in the process, delivering something like justice for the women who never saw him answer for his alleged abuse in court after he died by suicide in federal detention last August. Maxwell will now stand in Epstein’s place.

In their case against Maxwell, federal prosecutors say she engaged—along with Epstein—in the sexual abuse of a minor in the 1990s, as well as conspired with Epstein to “entice” three minors into “sexual activity for which a person could be charged with a criminal offense.”

The most serious charges against Maxwell involve “enticement,” as defined in a part of the U.S. criminal code that began its life in the early twentieth century as the Mann Act. The conduct criminalized in the Mann Act was once far more expansive, including transporting women and girls across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Since its original passage in 1910, the Mann Act has been used to prosecute people who were engaged in consensual conduct—like the Black boxer, Jack Johnson, after marrying a white woman—with the Supreme Court affirming such a broad application of the law in 1917. The “immoral purposes” language was updated in 1986, replaced with “any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense.” That still-broad definition is used now to charge Maxwell, because the victims she is accused of enticing into and, in one case, engaging in sexual conduct with were minors.

What Maxwell is not charged with is sex trafficking. But that is how some media outlets reported her arrest, with others describing the charges as being in connection with Epstein’s “sex trafficking ring.” The key federal law defining sex trafficking is the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, under which Epstein was charged for acts he is accused of committing in the 2000s. Maxwell is charged for criminal acts allegedly taking place before that law passed, and so was charged with a different crime—that older offense—on the books at that time.

This may sound a bit like hair-splitting, but these competing ideas of what “sex trafficking” means to the press and public alike matter. When sex trafficking is thought of as a sophisticated international operation to generate millions of dollars from kidnapping women and girls, holding them captive, and arranging for men to sexually abuse them—something that the vast majority of sex trafficking cases do not involve—a lone rich person abusing his power, particularly one with access to lawyers like Alan Dershowitz and presidents and royalty in his contacts list, can glide by, while even otherwise zealous anti-trafficking prosecutors look elsewhere. Simply put: Epstein didn’t fit the “trafficker” profile, particularly as it is reinforced by anti-trafficking campaigns from the U.S. government, in which traffickers are imagined as literal shadowy men of color. As much as fighting sex trafficking has been framed as the kind of universal pursuit people can unite around, it has never been a value-neutral project.

Men like Jeffrey Epstein did not need to head to Craigslist or Backpage to find women and girls. He allegedly had Ghislaine Maxwell for that, who, according those who say she essentially delivered them to Epstein, approached them outside Manhattan high schools or at Mar-a-Lago. The indictment describes Maxwell using her presence as a woman to gain victims’ trust, taking girls on shopping trips and trying to befriend them, to “normalize” abuse.

It’s not that the Justice Department was unaware of Epstein. He was facing a federal indictment 15 years ago, as Julie K. Brown at The Miami Herald reported, “accused of assembling a large, cult-like network of underage girls—with the help of young female recruiters—to coerce into having sex acts behind the walls of his opulent waterfront mansion as often as three times a day, the Town of Palm Beach police found.”

Yet in 2007, a federal prosecutor worked with Palm Beach prosecutors to cut a secret deal with Epstein’s attorneys, preventing him from facing federal charges. At the same time, as Brown writes, the deal also “essentially shut down an ongoing FBI probe into whether there were more victims and other powerful people who took part in Epstein’s sex crimes.” (That prosecutor was Alex Acosta, whom Trump appointed to head the Labor Department and who, once Epstein was indicted in 2019, stepped down.) As the Justice Department turned away from Epstein, it ramped up other sex trafficking prosecutions: Between 2005 and 2015, Black men were charged in 59 percent of federal sex trafficking cases involving minors and in 43 percent of sex trafficking cases involving adults (according to an analysis by human trafficking researcher and Texas Christian University political scientist Vanessa Bouché).

It is not incidental that the Mann Act, one of the first federal laws against (what is now called) “sex trafficking,” was also named the White-Slave Traffic Act. The law helped institutionalize the figure of the sex trafficking victim. As historian Jessica R. Pilley shows in her 2014 book Policing Sexuality: The Mann Act and the Making of the FBI, the victim imagined by the Progressive Era advocates of the law was a sexually innocent, American-born white girl. To then call her condition “slavery” was not meant as sensationalism but to explicitly liken “white slaves” to enslaved Black people. Such advocates, in pushing their narratives of white slavery, “consistently contrasted white sex slaves’ bondage with the bondage of African Americans.” Their conception of white slavery, Pilley adds, held the American imagination from the 1880s through the 1910s—the era of Jim Crow and when the sexual abuse of Black women and girls was not seen, by advocates or prosecutors, as an equal concern to that of “innocent” white girls.

But such innocence is never uniformly applied. Many of the women and girls Epstein targeted some hundred years later, as journalist Brown showed in her investigative reporting, were never afforded the “good” victim status. “Most of the girls came from disadvantaged families, single-parent homes or foster care,” she wrote. Their class background and experiences of poverty pushed them outside of that charmed circle of perfect victimhood. As one of them, Courtney Wild, told her, “Jeffrey preyed on girls who were in a bad way, girls who were basically homeless. He went after girls who he thought no one would listen to and he was right.” When Epstein was charged in Palm Beach County in 2005, the prosecutor declared there were “no victims” in the case, according to documents obtained by The Palm Beach Post. Prosecutors brought the case before a grand jury, where proceedings are secret, and where, as opposed to a criminal trial, they can even more significantly shape the outcome. Usually, they do so in their own favor—the defense has no attorney, can call no witnesses. But in this case, they appeared to make Epstein’s attorneys’ points for them, undermining the alleged victim they called as a witness.

Jurors heard from only one of the 13 girls who had told police Epstein abused them, and according to sources with knowledge of the grand jury proceedings, The Palm Beach Post reported, “Prosecutor Lanna Belohlavek peppered the girl with questions about her social media pages.… The girl’s MySpace account, supplied to prosecutors by Epstein’s lawyers, portrayed her drinking liquor with boys and talking about sex.” Documents later showed that one of Epstein’s attorneys, Alan Dershowitz, had provided the copies of her social media.

The prosecution could have called as witnesses any of the 12 others who came forward; they only approached three, giving them two days’ notice. One said she never received her subpoena. “I never had a chance for my voice to be heard,” Wild told The Palm Beach Post. “My voice was muted by the same government that was supposed to protect me.”

Epstein was able to evade prosecution in part because he didn’t fit the profile of a “sex trafficker.” But he was aided by myths about the girls who say he abused them, who were seen essentially as incapable of being victimized. Such myths helped people like Ghislaine Maxwell and others around Epstein insulate him—including those in the justice system.