On November 29, Syrian rebels breached the western limits of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city in the north, which had suffered the greatest destruction of any city in the country’s 13-year-long civil war. The offensive triggered the “death spiral” of Bashar Al Assad’s regime, as a mixed coalition of former rebels, local strongmen, and regular people, suddenly emboldened, captured the southern city of Daraa, near the border with Jordan. Rebels from the north, led by the Islamist faction Hayat Tahrir Al Sham, or HTS, continued to push toward the capital city of Damascus, while popular uprisings swelled in the south. Within two weeks, Assad fled to Moscow without a last word—the unceremonious end to a 54-year autocracy.

What happens next? Tensions are simmering between HTS and other factions, particularly the Turkish-backed militias who oppose the relative autonomy of the U.S.-backed Kurds to the country’s east. The United States vowed to continue its own military operations in Syria’s northeast against remaining pockets of ISIL and Iranian-backed proxies. Israel has dropped hundreds of bombs all throughout Syria since the fall of Assad and even seized a swath of southern territory, a “buffer zone” northeast of the Golan Heights.

Some parts of the Syrian population are fearful of HTS, which the U.S. still categorizes as a terrorist organization, and which has previously targeted and detained political opponents, activists, journalists, and other critics and enforced gender segregation in its schools. More recently, it has presented itself in more “moderate” terms. Assuaging fears from the business elite, Syria’s new government said it would soon “adopt a free-market model,” shedding itself of state-controlled industries and liberalizing its economy, a shock treatment of sorts to propel international investment. In his first interview with U.S. press in 2021, Abu Mohammad Al Jolani, HTS’s leader and a former Al Qaeda fighter, declared the region he controlled “does not represent a threat to the security of Europe and America.” But what of regular Syrians?

That remains an open question. In the meantime, the streets are flooded with people celebrating the fall of Assad, refugees in Turkey are planning their return home, and prisoners—some of whom have been held in brutal conditions for years—are being liberated. As we speak, people mourn the dead and search for the missing, hoping for the best.

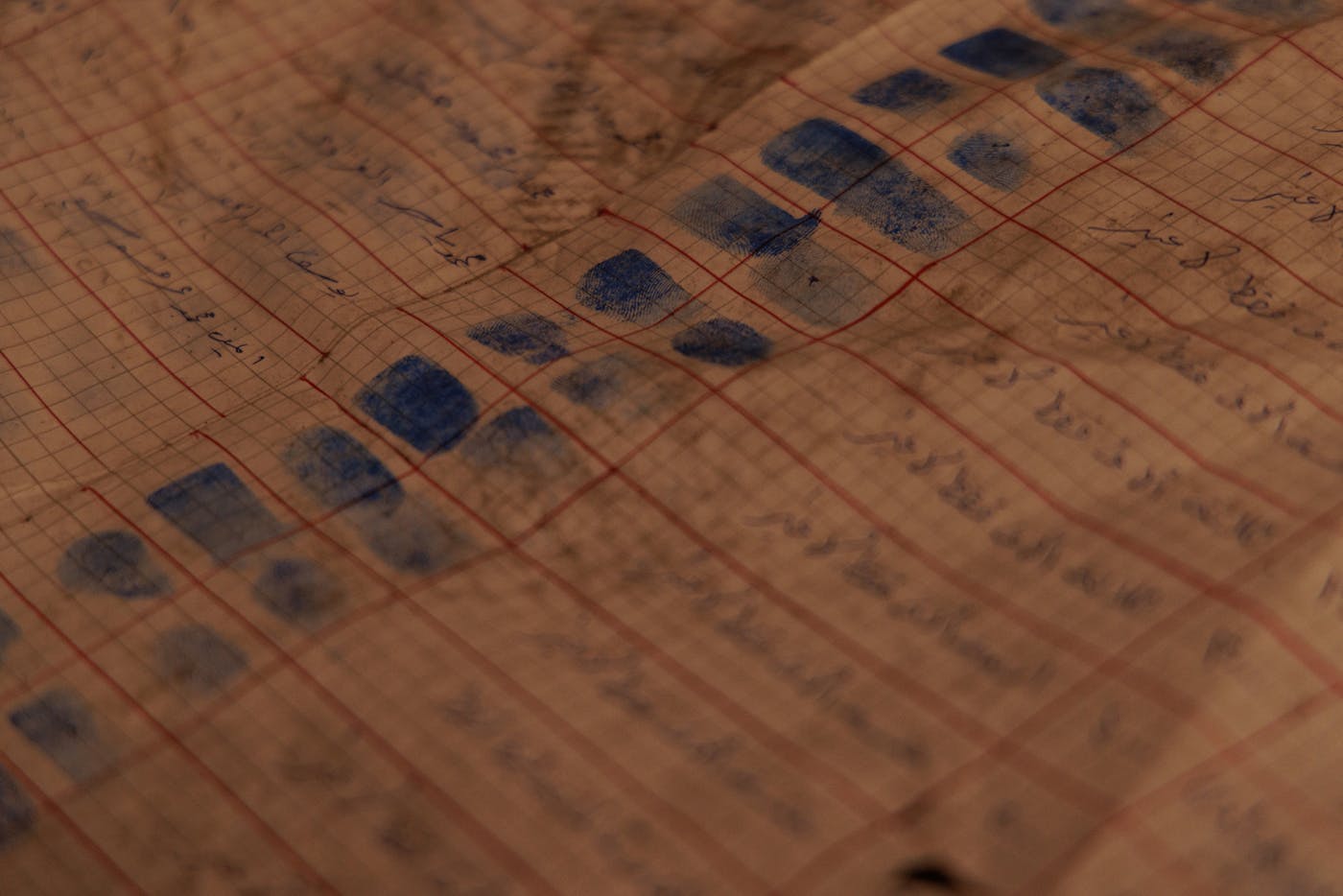

![Left: Ahmed Al Malali, age 67, holds a phone with a picture of his nephew, Saleh Hadeed Al Malali, age 44. Saleh was accused of terrorism and sent to prison in 2014. Right: Berkhawi Khalaf Al Hamed, age 62, stands for a picture in Sednaya Prison. He visited the prison looking for information about his son Fadhel Berkhawi Al Hamed, born in 1985 in Al Kamishli, who was sent to prison in 2018. "In 2020, I was waiting for a supposed pardon that Bashar Al Assad was going to give to some prisoners. The pardon never arrived," he said. "I couldn't afford the 20 million Syrian pounds they were asking for to visit him [in prison]." Many relatives said their imprisoned family members requested they avoid visiting the prison, because they were often beaten and heavily mistreated after family visits.](http://images.newrepublic.com/62150dbb095d6d4cf1db6a89df5f5999e72a978b.png?w=954)