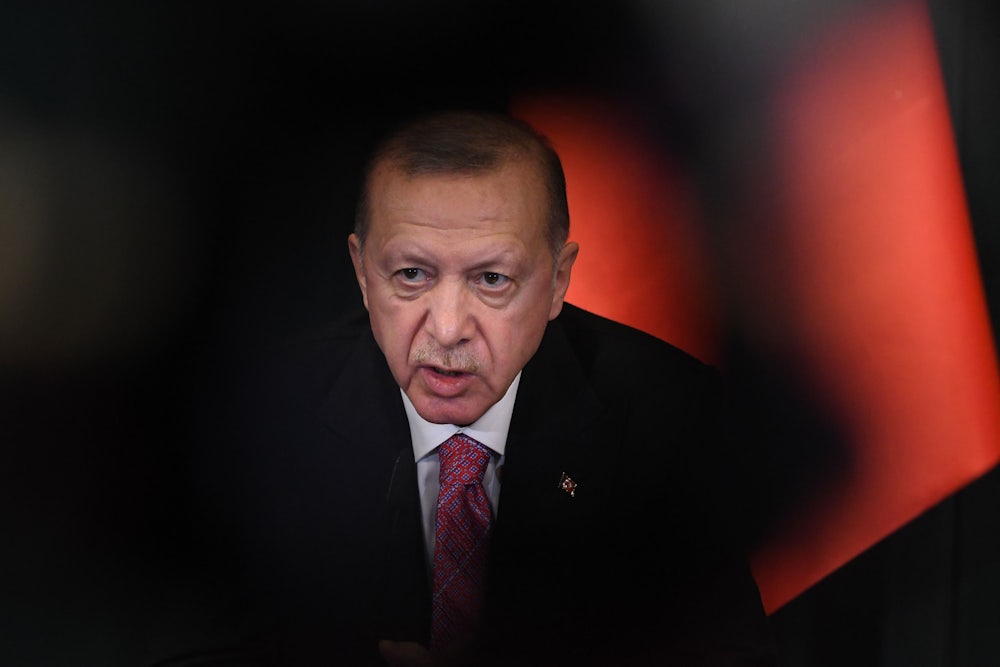

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has come under fire for his government’s poor response to the deadly earthquake that rocked his country and neighboring Syria last week, but the problems started long before. And despite the scope of the tragedy, he may yet emerge from the ashes victorious.

More than 41,000 people have died and thousands are hospitalized since southern Turkey and neighboring Syria were hit by a 7.8-magnitude earthquake last week. The quake is among the worst natural disasters in the world this century and the deadliest in Turkey since 1939. People are struggling to find shelter in the freezing winter weather amid an ongoing economic crisis.

“The country already had a lot of problems,” said Gonul Tol, the author of Erdogan’s War: A Strongman’s Struggle at Home and in Syria. She cited “serious economic problems’’ and “hollowed-out institutions.”

“This earthquake just compounded everything,” Tol told The New Republic.

Erdogan has led Turkey for two decades, ironically sweeping to power following a devastating earthquake in 1999, and is up for reelection in May. He insists that the earthquake response is under control. Critics, however, have slammed the government’s lack of preparedness and slow response time.

Since taking office, Erdogan has hobbled civil society organizations and staffed his government with party loyalists, instead of people who know how to respond to a natural disaster. The centralization of response groups has also hampered operations in Syria, which must rely on foreign aid that has to go through Turkey, where the roads have been badly damaged.

Most of the actual work on the ground has been carried out by volunteer organizations, many of whom have complained of a lack of federally supplied resources.

Soli Ozel, a lecturer at Kadir Has University in Istanbul, told NPR that federal funds intended for natural disaster relief were instead spent on construction projects run by the president’s allies.

Such construction projects helped propel Erdogan’s success. One of his government’s top achievements was the construction of new housing. But in a recently recirculated video from a 2019 campaign stop, Erdogan brags about flouting construction safety regulations on housing projects in Maras province—some of the very projects that collapsed during the quake, killing the residents.

“If you have a government that puts the interest of a corrupt few above all else, this is what you’ve got. You get a deadlier disaster,” said Tol. “And I think … people see that. People understand that. And that’s why people are very, very angry.”

“Politics, and bad politics, paved the way for today’s disaster.”

For the first time, Erdogan’s political future does not look secure. Before the earthquake, the opposition parties had struggled to present a united front against him and were not expected to do well in the elections. But they have come together in the wake of the disaster, placing the blame for it squarely on Erdogan.

“If there is one person responsible for this, it is Erdogan,” opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu said last week.

According to Lisel Hintz, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, the earthquake “may provide a platform from which [the opposition] can speak with a united voice.”

It “brought into stark relief how the government has failed the people,” she told TNR.

Hintz explained that the opposition views the upcoming election as crucial to finally unseating authoritarianism in Turkey.

Both she and Tol think it’s likely Erdogan will postpone the vote. He declared a state of emergency that would last until the eve of the election. Unless the situation improves significantly by then, it’s unclear how holding an election in May would even be logistically possible.

Whether or not he does postpone the election, Erdogan could still pull off a win. He is a master at turning bad situations to his advantage, as he did in 2016, when he managed to galvanize his supporters via social media into stopping a coup attempt.

If Erdogan mobilizes every state resource and produces a coordinated disaster response, he could succeed at shifting public opinion in his favor, according to Tol.

Or, more simply, he could clamp down on the narrative. The Turkish government has long been criticized for silencing dissident voices and passed a law in October banning the spread of misinformation—as it defines it. Federal prosecutors are already investigating two journalists who published stories criticizing the earthquake response.

The government also temporarily blocked access to Twitter, claiming it was trying to stop the spread of misinformation about the earthquake. Thousands of people had taken to Twitter to share real-time videos and photos of the disaster and the lack of government response. The shutdown also further hindered relief efforts, because eyewitness accounts are incredibly useful to responders trying to assess the extent of the damage and the resources needed.

Erdogan and his party are “pulling out all the tools in the authoritarian toolkit to tilt the election in their favor,” Hintz said. They could even hold the elections at the originally set time.

She noted that Turkey’s last election was held under a state of emergency, and Erdogan pulled off a win, albeit a narrow one. “They might try again,” Hintz said.

“This question of remaining in power is an existential one for Erdogan,” she explained. “That incentivizes him to take risks.”