In the summer of 2020, as countries around the world struggled to survive the early surge of the pandemic, battling both economic and public health crises, a number of nations had to face the compounding effects of devastating sanctions imposed by the United States. In Syria, doctors were unable to rebuild hospitals or import medical goods. And in Iran, the Brookings Institute estimated that between May and September, there were about 13,000 additional deaths as a result of U.S. sanctions. Although in theory these sanctions should contain certain humanitarian exemptions, companies often over-comply with rules out of fear of being punished. The Trump administration refused to ease these sanctions, and the consequences were catastrophic.

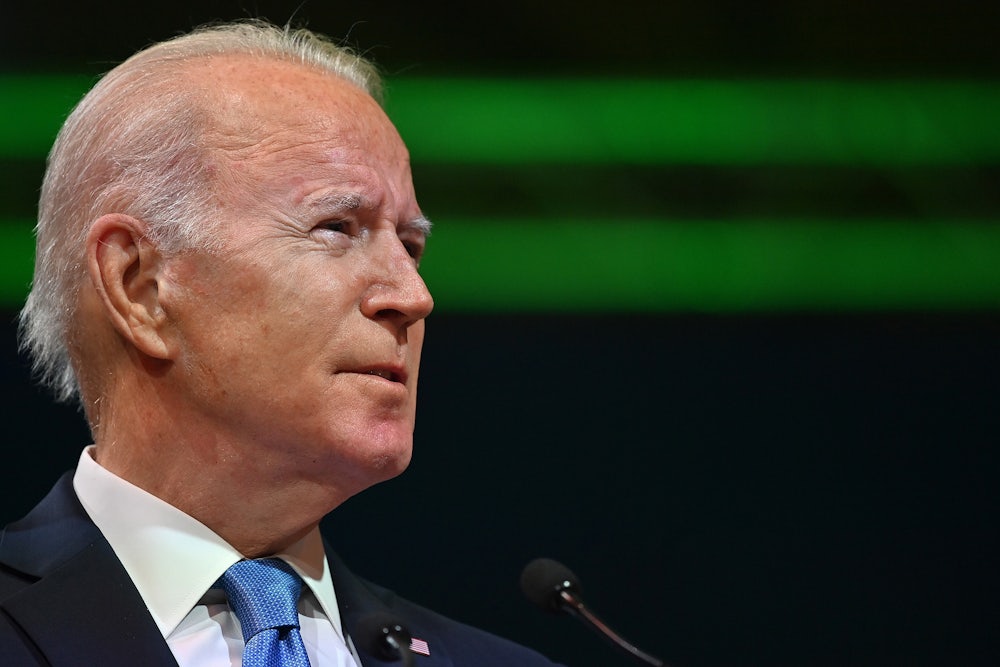

This October, in response to these and other concerns, the Biden administration published its review of current foreign sanctions policy. This was in keeping with a promise Biden made to voters: Throughout his campaign, he pledged to reorient his foreign policy around diplomacy and human rights. True to form, within a few days of assuming office, the Treasury announced that it would be looking into the way sanctions had been strategically deployed, signaling that a long overdue reconsideration was coming. But the result, a nine-page memo, did little more than spell out a number of accepted realities: that U.S. sanction use has grown in the last 20 years; that the composition of sanctions has changed during that time frame; and that sanctions can have a material cost on adversaries. Overall, the review seemed to avoid any serious self-reflection or criticism. It was hardly surprising that advocates of sanctions reform offered dim reviews of the effort.

The problem with America’s current sanctions regime, critics say, is twofold, beginning with the question of whether sanctions can be meted out in a way that comports with larger humanitarian efforts. Broad-based U.S. sanctions are purportedly put in place to hold adversarial governments accountable for their actions. But in practice, ordinary civilians in countries ranging from Venezuela to Iran to Syria are consistently made to bear the brunt of this economic warfare. During the Covid-19 pandemic especially, not only did countries burdened with the weight of U.S. sanctions suffer in terms of poverty and inflation, but sanctions also created situations in which it became more difficult for medical supplies and other necessary resources to combat the pandemic to reach the people who needed them most. Given that the ostensible impetus for the sanctions review was a desire to mitigate some of the crushing compounding effects of sanctions and the pandemic, it was notable that the report hardly mentioned the humanitarian impacts.

But the realities of the pandemic illuminated the ways our sanctions regime consistently came up short on the humanitarian front; it also raises important questions about whether sanctions are effective deterrents overall. While sanctions can naturally cause measurable material hardships for a targeted country, the real benchmark of any sanctions’ success should be whether, once imposed, they are effective in altering a wayward nation’s policy calculus.

The track record of sanctions leaves much to be desired. In places like Cuba, Venezuela, and Syria, sanctions have been in place for years. And yet there is little to no evidence that their imposition has done much to change these nations’ actions or behavior, either in the sense of changes to domestic policy specifically or their relationship with the U.S. more broadly. In Syria, argues Joshua Landis, chair in Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, they have, in fact, had the opposite effect. By undertaking policies that weaken not only Syria but also its neighbors, the U.S. has ensured that Damascus remains entirely dependent on Iran and Turkey. “The sanctions are really defeating America’s major policy interests in the region,” he says.

The Trump administration accelerated a trend to turn sanctions into a tool of first resort in U.S. foreign policy. In the last two decades, U.S. sanctions have multiplied at a dizzying rate—a 933 percent increase in Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions designations since 2000, according to the Treasury review. Moreover, their unsparing use has only blunted their efficacy further: Sanctions have become such a preeminent tool in the American tool kit that government officials seem to have lost track of their ultimate goals.

In response to the escalating violence in Ethiopia and Eritrea, the Biden administration announced that it would be imposing sanctions on Eritrea’s military. Shortly thereafter, The Washington Post reported that those sanctions were “unlikely to have immediate consequences for the war in northern Ethiopia … according to multiple diplomats,” a strange admission considering that policy implications should in theory be the driving force behind coercive methods like economic sanctions. Material punishment should be the means to an end in sanctions policy, not the goal in and of itself.

This is hardly the first time that humanitarian concerns have portended a shift in American sanctions policy. “In the early ’90s, there was tremendous hand-wringing, in at least the progressive policy circles, over the horrible impact of sanctions on the Iraqi civilian population,” note Sarah Leah Whitson, the executive director of Democracy for the Arab World Now. “That was a very dominant topic of discussion. Thirty years later, where are we? Sanctions have exponentially increased.” Even if humanitarian concerns surrounding sanctions are more heightened, there is little policy evidence to support that shift.

The one example that is consistently touted as a success for sanctions is the Obama-era tightening of the screws on Iran, which, in the telling of supporters, brought Iran to the negotiating table, eventually yielding the Iran nuclear deal, or JCPOA. Even that account, however, has been disputed. But this singular success story only points up the failures of the overuse of sanctions, according to Marcus Stanley, advocacy director at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “We’re so hooked on sanctions that we got what we wanted and then we canceled what we wanted and reimposed sanctions,” he told me. “And now, we won’t guarantee to lift the sanctions if they go back to doing what we wanted.”

Can the implementation of specific, individual sanctions resolve questions about whether they can be deployed in a humanitarian manner, as well as in a way where they become more effective at changing the policy trajectory of other nations? On the matter of humanitarianism, the answer would apparently be yes, so long as they are imposed purposefully. There are risks to implementing any kind of sanctions without giving specific thought to how to avoid humanitarian harm. “I think there’s a big danger,” Stanley argues, “in saying that the adjective targeted or smart somehow means that sanctions will not be a form of collective punishment or destructive to innocent civilians.”

If officials do a more thorough job of tailoring the sanctions and thinking through the knock-on effects of their imposition, it may be possible to leave ordinary citizens unharmed. But there are still important concerns about their effectiveness that have been left unaddressed. The U.S. government already occasionally sanctions individuals, alongside the nations that are subject to broader embargoes or sectoral sanctions. This so-called “naming and shaming” approach is an important signaling mechanism and can be used to uphold international norms.

But these are often lazy and haphazard punishments that amount to nothing more than a slap on the wrist. “They’re ‘feel good,’” Landis says, about targeted sanctions on Syrian President Bashar Al Assad and his inner circle. “I don’t think putting severe sanctions is going to change his policies in any fundamental way. He’s always going to be able to find people who are willing to work within those parameters,” he added.

For the most part, when the Treasury Department has elected to use these sanctions, they have come as a knee-jerk reaction to a country or an actor doing something that the U.S. deems unacceptable. Without much more thought beyond satisfying some immediate need to react to a foreign government’s action, the sanctions rarely succeed in changing behavior, and adversaries may even wear the designation as a badge of honor. To the extent that the effects are felt on those individuals’ bank accounts, these actors can typically find ways to navigate around the harshest of punishments and keep the boodle flowing.

“We try to advocate going after the commercial interests of those either engaged in corruption or perpetrating atrocities. Hitting their pocketbooks is where it really hurts, as opposed to the purely symbolic action,” says Justyna Gudzowska. Gudzowska works at The Sentry, an organization dedicated to tracking “the dirty money connected to African war criminals and transnational war profiteers [and that] seeks to shut those benefiting from violence out of the international financial system.” The Sentry’s founders discovered that neither the broad-based sanctions imposed on Sudan, nor individual sanctions in Zimbabwe, nor even the diplomatic efforts in Ethiopia or Eritrea were doing much to curb war crimes or human rights abuses.

The Sentry advocates for a new approach, which aims to target the entire financial network of supposed bad actors in order to affect their coffers and, ultimately, create tangible changes. The Global Magnitsky Act, passed in 2012, gives the president a new weapon in the fight: the authority to impose sanctions on individuals identified as engaging in human rights abuse or corruption. And while it is too early to tell if sanctions applied under the Magnitsky Act will ultimately prove to be a successful alternative, Gudzowska points to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as an exemplar: The implementation of sanctions against Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler in 2017 has been credited as one of the primary reasons why his friend Joseph Kabila, who had been president of the DRC for almost 20 years, decided not to run for reelection in 2018.

It’s a promising example of what’s possible in a reformed sanctions regime: When world leaders are dependent on international financial institutions, and when a clear political outcome is being pursued, sanctions can deliver tangible change without spreading unwelcome economic hardship to innocent civilians.

For any of these approaches to be successful, sanctions cannot be the only tool, nor can they be—as they have recently become—a tool of first resort. Indeed, sanctions are likely only to be effective if used sparingly, specifically, and in conjunction with other approaches, notably diplomacy, which has become an increasingly weak part of American foreign policy in the past few years.

While the administration’s review of America’s sanctions regime fell short of what reformers have sought, its mere existence offers some hope that a more substantial rethinking is at hand. This would at least be in keeping with some of the progress the Biden administration has already made on the foreign policy front: If the president is now willing to question the reasoning behind open-ended military deployments, like the one we’ve ended in Afghanistan, then the time is ripe to find an alternative to the status quo policy of reaching for equally infinite economic strangulation as a matter of first resort, as well.