Early in his presidency, Barack Obama addressed an audience at Cairo University in an attempt to improve America’s standing in the Arab world. Titled “A New Beginning,” the speech called for “mutual interest and mutual respect” between the United States and Muslim-majority countries, a reciprocal association that would expunge the tensions that characterized the Bush administration’s relationship with Middle Eastern nations. In explaining how relations between the U.S. and Islam had deteriorated, Obama mentioned, among other list items, “a Cold War in which Muslim-majority countries were too often treated as proxies without regard to their own aspirations.” The Atlantic called the talk “brilliant” and “public relations magic.”

Alas, it was more like a magic trick, fascinating to watch but devoid of substance. Obama’s effort to reverse America’s unpopularity among Arab nations failed, not least because a relationship defined by mutuality never materialized. After cutting off aid to the Egyptian military in 2013 for its role in a coup, the Obama administration restored the funds two years later, underwriting a vicious government that represses its people. In a 2016 interview with The Atlantic, near the end of his tenure, Obama was quoted joking with aides that, “All I need in the Middle East is a few smart autocrats.”

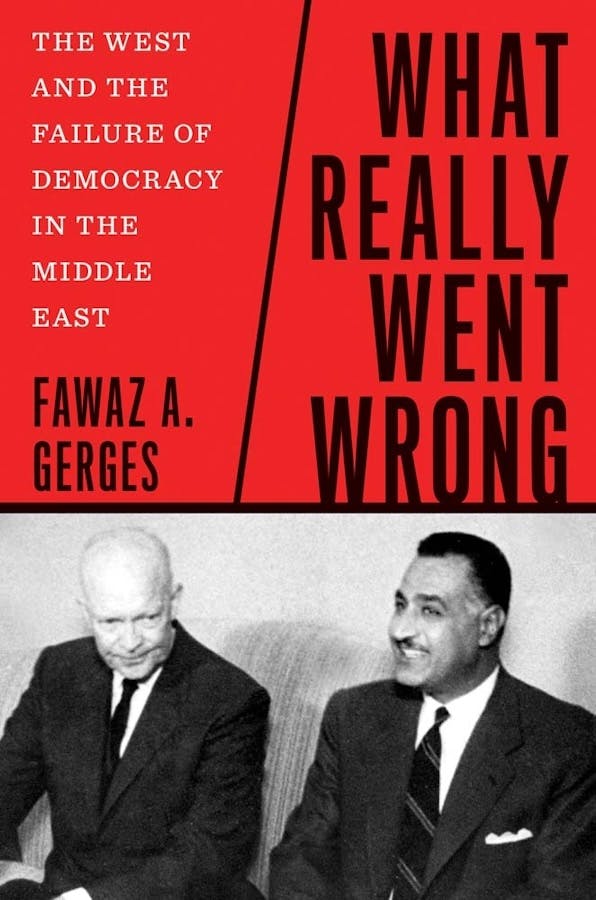

The implosion of Obama’s vision—and his replication of Cold War–era American policies that ran roughshod over human rights in the Middle East—serves as a sharp illustration of the dynamic that Fawaz A. Gerges outlines in his new book, What Really Went Wrong. The title is a sly allusion to a work by the late historian Bernard Lewis, What Went Wrong? In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Lewis’s slim volume became a surprise international bestseller, selling in huge numbers not just in the U.S. but in places like Denmark and Italy. In Lewis’s view, radicalized Muslims attacked America because they wrongly blamed us for the failings of the Islamic civilization to adapt to the modern world. Its author advised the Bush administration about the benefits certain to accrue if the United States invaded Iraq, permanently tarnishing his reputation.

Gerges, a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, tells a very different story. In his account, the sources of anger at the United States in Muslim-majority countries, and the woeful situation in Arab lands, stem from postwar American foreign policy—particularly that of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration, which lasted from 1953 to 1961. During those tense, youthful Cold War years, Ike made fateful decisions to defy the wishes of the bulk of the population in Iran and Egypt, rejecting their governments and marginalizing their leaders. At a time when much of the region was asserting independence from colonial rule, the U.S. decisively intervened in these two critical countries in the name of anti-Communist paranoia, to the detriment of their long-term economic and democratic development. “America’s post–World War II imperial ambitions and its offensive conduct in the early decades of the global Cold War trigged something resembling a geostrategic curse in the Middle East,” Gerges writes.

In 2024, the U.S. faces some of the same challenges in the Middle East that it did in 1954: Our

allies are repressive and unpopular with their own people, while hostile leaders

benefit by antagonizing the United States. As a guide to some of the worst

policymaking of the Cold War, Gerges’s book is instructive, though far from

groundbreaking. As a jumping off point for better U.S. policy in the future, however,

it is sometimes perplexing, often missing a sense of the range of factors that

shaped policy on the ground and proffering unsound solutions. In order to think

about resetting American policy in this region, we need to clearly understand

the dangers of aligning ourselves with autocrats—even ones that are anti-colonial

and popular.

After World War II, the United States didn’t

just stand alone as the world’s greatest power (William T.R. Fox coined the

term “superpower” in 1944), it materialized as a rare Western country without any

history of imperialism in the Middle East. The few contacts Americans had with

the region came primarily from Christian missionaries. This distinguished the

U.S. from the French and the British, who had done considerable damage in the

region, beginning with Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Egypt in 1798. The

Soviet Union (along with the Brits) also occupied much of Iran and refused to

leave the country in 1946, as they had agreed. Iranians were thus generally and

uniquely well disposed toward Americans as the Cold War dawned.

In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh became prime minister in Tehran. He was an idiosyncratic man prone to strong public displays of emotion and making television appearances in his pajamas. But Mosaddegh was both a charismatic democrat and a deeply committed nationalist, the type of leader rare to find in the Middle East (or anywhere else, for that matter). He favored an independent judiciary, transparent elections, and the freedom of worship and association, policies that could provide Iranians with dignity and decency.

For decades, Mosaddegh had opposed Britain’s stranglehold over his country’s lucrative oil reserves, insisting that the commodity should be developed to primarily benefit Iranians, not a foreign empire. (Winston Churchill called Iranian oil “a prize from fairyland beyond our wildest hopes.”) When he moved to nationalize Iran’s oil reserves, the United Kingdom deployed sanctions and political sabotage to undermine and attempt to overthrow Mosaddegh. Like others in the Middle East, the prime minister hoped the U.S. would act differently from other Western countries. He hoped it would recognize his country’s quest for independence and sovereignty, or at least not subvert its efforts. For a time, his hopes were realized. Harry S. Truman’s administration opposed the nationalization scheme but warned the Brits against ousting Mosaddegh, a caution they reluctantly heeded.

But Truman’s successor had no such hesitations about using covert operations in Tehran. In 1953, Eisenhower and his Secretary of State John Foster Dulles green-lighted a CIA-backed coup to replace Mosaddegh and replace him with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a far more pliant anti-Communist (and less of a stickler for human rights). It was the first instance of America’s youthful intelligence agencies directly deposing a disfavored foreign government. “The operations against Mosaddegh became a template for frequent U.S. direct and indirect interventions in the developing world in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s,” Gerges writes. Pahlavi led Iran ruthlessly until 1979, when Islamists fomented a coup and forced him into exile. The Islamic revolution and related takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran poisoned U.S.-Iran relations, which have never recovered and whose breakdown may yet still lead to a horrible, unnecessary war.

Unlike Mosaddegh, Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser was no democrat, though the two men shared a disdain for British colonial rule. Nasser’s nationalist sentiments deepened while he served in his country’s military in the 1948 war with Israel. In 1952, he fomented a coup that toppled the deeply corrupt King Farouk and brought him to power. As he abolished the oligarch-friendly monarchy and declared Egypt a republic, Nasser banned all political parties and arrested thousands of critics—notably, members of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist group that influenced Hamas and Al Qaeda generations later. Utilizing Egypt’s unique position and history in the region, he fashioned a pan-Arabism that aroused the passions of Middle Easterners like no other modern leader before or since.

Like Mosaddegh, Nasser hoped for good relations with the United States but refused to be its puppet, determined for Egypt to chart a neutral course in the Cold War while he furthered the country’s economic development. He enjoyed some successes in this endeavor, most strikingly in 1956; after Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, the U.S. lambasted Britain, France, and Israel for attacking the Sinai in response, with Eisenhower even threatening sanctions against all three countries. The event simultaneously marked the demise of the British Empire and the high-water mark of Arab nationalism, as Nasser was perhaps the most popular leader in what was then called the Third World. But he privately recognized the crucial role United States played in persuading the three Western countries to withdraw from the Sinai.

Alas, this moment would prove the apex of Egyptian-American relations during Nasser’s time. Eisenhower and Dulles were exasperated at Nasser’s inability to reciprocate their gestures of goodwill, and they perceived pan-Arab nationalism as hostile to the U.S., leaving the resource-rich region vulnerable to Soviet penetration. And indeed, Nasser looked to Moscow to finance a dam after Americans withdrew their offer to provide funds, and his verbal attacks on the closest U.S. allies further alienated policymakers. It wasn’t just the Eisenhower administration that cooled on Nasser, either. The journalist Warren Bass convincingly demonstrated in his book Support Any Friend that the U.S.-Israeli alliance solidified as Ike’s successor, John F. Kennedy, appreciated the Jewish state’s reliability while Nasser flirted with the Soviets.

In 1967, Nasser made a fateful miscalculation in publicly and repeatedly declaring his objective of destroying Israel and overestimating his chances against the Jewish state in a military conflict. Within days, Israel destroyed much of the Egyptian military, along with the hopes that pan-Arabism had instilled in the region for a glorious, powerful future. When Nasser died in 1970, he was still beloved among Arabs but was a far weaker figure than he had been years earlier. His vision of a prosperous Middle East unencumbered by outsiders was destroyed and remains dormant nearly 60 years later.

So far, so good. Gerges’s account of the reigns of Mosaddegh and Nasser is serviceable, though these episodes are already well known and receive only summary treatments here. Instead, What Really Went Wrong’s novelty (such as it exists) comes from its argument linking the U.S. disdain for these two men in particular with the region’s contemporary woes. Mosaddegh and Nasser were not typical leaders, Gerges suggests. They were uniquely patriotic, popular secularists who were somewhat friendly to the United States and could have led the region out of the morass it was in (and remains). “The defeat and marginalization of secular-learning nationalist visions in Iran and Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s,” he argues, “allowed for Sunni and Shia puritanical religious narratives and movements to gain momentum throughout the Middle East.”

In the case of Iran, Gerges’s brief is inarguable. Of all the crimes the U.S. committed during the Cold War—a long and bloody list—the CIA’s toppling of Mosaddegh was among the most self-defeating and carried perhaps the longest-lasting consequences. By succumbing to Cold War paranoia and denying Iranians a precious opportunity for democracy, the U.S. consigned them to a vicious autocrat for more than 25 years. The Islamist government that replaced the CIA-approved Pahlavi was (and remains 45 years later) equally repressive but also anti-American, crushing all things liberal at home and supporting groups like Hezbollah and Hamas abroad.

And yet, while making an unimpeachable case against the CIA’s actions in Iran, Gerges fails to explain how the Western world could have prospered without access to petroleum. He invokes the American desire for robust oil supplies numerous times but never takes the issue seriously. “From the beginning of the crisis to the end, the U.S. government opposed Mosaddegh’s nationalization of oil because that would have created a precedent that threatened America’s interest in an open global economy,” he writes, disapprovingly. But these were not superfluous concerns. America—and Western Europe, Japan, and all NATO countries—needed large supplies of oil for their economies. It was hardly just corporate greed motivating these priorities. U.S. policymakers should not have responded to this task by installing or supporting a friendly dictator in Iran or anywhere else—they could have worked with Mosaddegh to ensure that Iranians benefited from oil profits while guaranteeing the resource kept flowing. But Gerges downplays the genuine geopolitical challenge facing American leaders, flattening the history and evading the problem of how to balance interests and values in foreign affairs.

A more serious flaw appears in the chapters about Nasser. Gerges values Nasser’s charisma, opposition to Western imperialism, and economic policies, so much so that he underplays the leader’s deeply consequential decisions to crush the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamists. He concedes “blemishes on [Nasser’s] record,” but does not elaborate on the implications of Nasser’s horrific treatment of his political opponents. Nasser created entire concentration camps for Muslim Brotherhood members, torturing them for years. His most notorious target was Sayyid Qutb, a deeply influential figure who urged violence against Nasser and other secular leaders as legitimate targets for being un-Islamic—and who identified the American enemy as supposedly bankrolling these secular leaders. This was, in fact, the birth of the aggressive perspective that would culminate, decades later, in ISIS, Hamas, and Al Qaeda, whose founding members (such as Egyptian-born Ayman Al Zawahiri) valorized Qutb.

Gerges knows this. In fact, he wrote an excellent dual biography of Nasser and Qutb in 2018 called Making the Arab World. The Egyptian leader’s brutality toward the Muslim Brotherhood “morphed into an armed clash between the Arab nationalist project represented by the Nasserist state and an emergent radical Islamist current led by Qutb,” he wrote in that book. But despite chronicling how Nasser’s viciousness toward Islamists birthed a twisted form of global jihad, he suggests in What Really Went Wrong that America should have aligned itself with Nasser because of his popularity and secularism. “Had it taken an anticolonial stance, Washington could have benefited from Nasser’s skills in staying nonaligned as the world lurched toward bipolarity,” Gerges writes. But supporting a well-liked dictator is hardly a recipe for long-term U.S. foreign policy success! Opposition parties, including Islamists, would have had more reason to hate America, not less, if the Eisenhower administration had taken Gerges’s suggested course.

Nasser embarked on a warmaking spree around the Middle East, viciousness that Alex Rowell covered in his 2023 book, We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World. Although Gerges mostly overlooks this aspect of Nasser’s career, Rowell’s work convincingly demonstrates that, however popular the Egyptian leader was for his pan-Arabism and opposing Western interference, his lasting impact was in influencing the establishment of like-minded police states in Syria, Libya, and Iraq. Nasser endorsed Arab unity so long as he was in charge, hardly a vision that Washington should have endorsed.

Deciding which horse to bet on in distant lands is not a game that U.S. policymakers can usually win. The variables are too many, the uncertainty too great. Favoring some leaders and groups means disfavoring (and angering) others. This is especially true in countries led by unpredictable, ruthless megalomaniacs. As the Biden administration considers a codified security alliance with Saudi Arabia, we are in danger of once again attaching ourselves to leaders who have contempt for their own people’s human rights. The real lesson of America’s Cold War policies is that interfering in other countries should only be done when our most vital interests are at stake, we have competent leaders, and we can do more good than ill. Since those stars rarely align, the U.S. should take a much more sparing approach to interventions. That is what really went wrong with American foreign policy.