President Donald Trump walks astride Russian leader Vladimir Putin, the man he calls “the toughest guy in the world, someone who has done tremendous things for his country.” Since making Moscow his first foreign trip soon after being reelected president in 2024, Trump has met with Putin three times in two years. Today marks the first time their meeting has occurred on Ukrainian soil, in Bakhmut, as Russian troops have overrun most of central Ukraine and are poised to conquer Kyiv in the coming days. Trump and Putin are joined by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko, and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev to shake hands and celebrate the lifting of U.S. sanctions against Russia, China, North Korea, and others.

At the press conference, Trump is the first to speak. “I am honored to be with, well, they were just saying I’m the greatest president in history, I don’t know if that’s true, Lincoln was OK, but that’s what they’re saying. And these guys,” he says, gesturing to the men sitting behind him, “they’re fighting to defend our freedom and our civilization. And they’re running their countries properly, they run it strong. With crime, with terrorism, they run it strong. And we’re replacing NATO with something much better today, much tougher.”

Traditional U.S. allies are uninvited to today’s event. Relations between the United States and the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Canada are strained after Trump called them “parasite countries” and referred to their leaders as “twits.” Australia recently recalled its ambassador to Washington after Trump insulted the country again by saying it should be “obliterated” for its trade policies. After he speaks, Trump takes a question from a reporter who asks about the absence of these long-standing friendly nations. “They’re losers,” Trump says. “Today, I’m happy to be standing with the winners.”

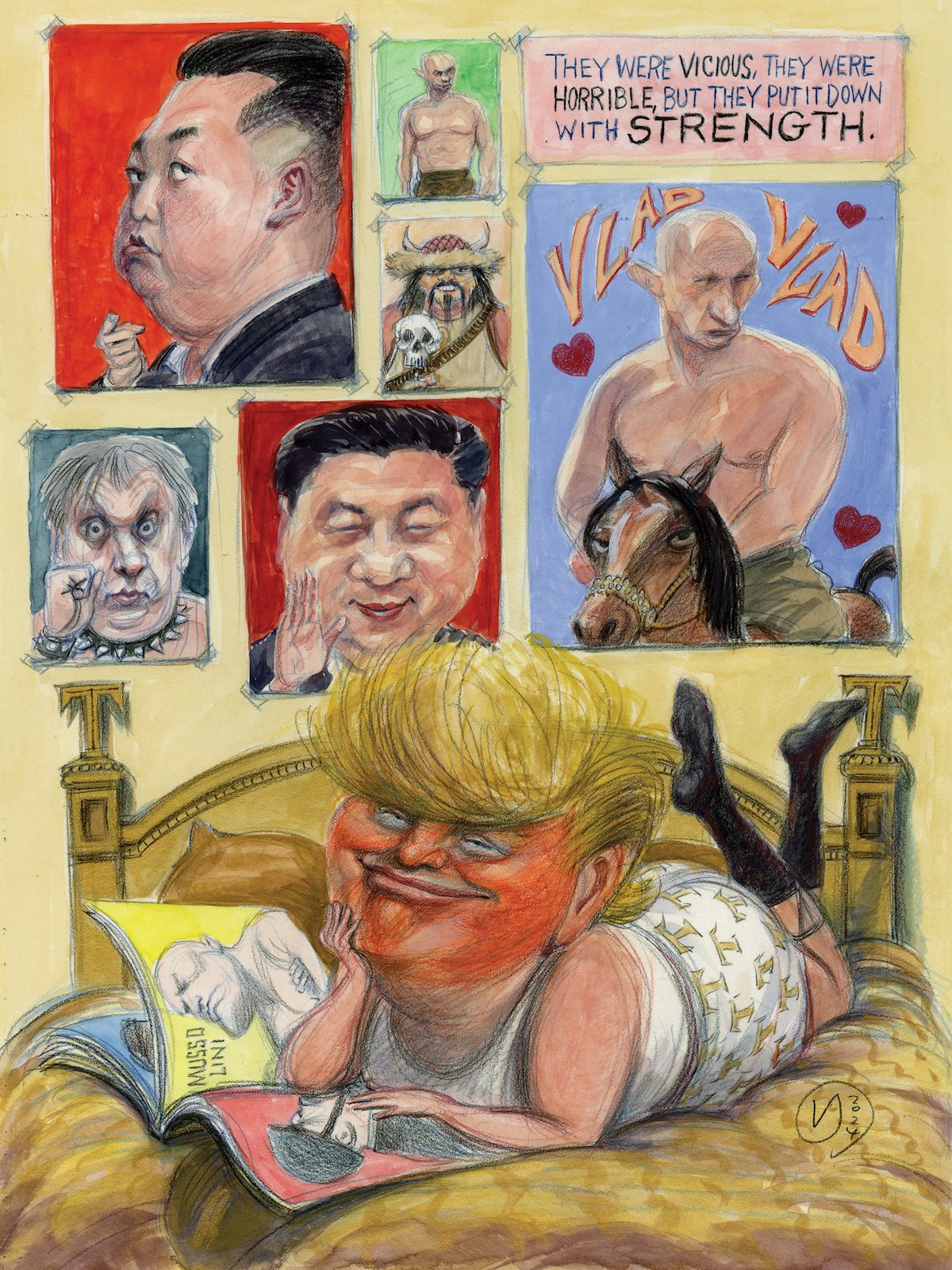

If this scenario seems impossible should Trump get reelected in November, then you haven’t followed Trump closely enough. About 25 years before he announced his first run for the presidency, Trump gave a revealing interview with Playboy magazine. Alongside his standard homages to the death penalty and fabrications about donating millions of dollars to charity, he talked in the 1990 conversation about a recent trip to the Soviet Union he had undertaken. He returned unimpressed with Mikhail Gorbachev, because the Soviet leader was weak. “Not a firm enough hand,” Trump said of the humane, courageous individual who ended 70 years of dictatorship and gave Russian democracy a precious historic opportunity. Trump reserved praise instead for the Chinese government’s massacre of students in Tiananmen Square that occurred the year earlier. “The Chinese government almost blew it,” he said. “Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength.” For Trump, brutality has always been a sign of strength, a trait to be admired and imitated. Conversely, things like respect for the rule of law, a free press, fair elections, compromise, and cooperation—all hallmarks of the democratic process—are despised.

Trump told Playboy he wasn’t seeking elected office, but of course, that determination changed in 2015. In between the interview and his presidential announcement, he switched his public positions on many things: abortion, health care, which of his wives he wanted to cheat on. But in a life filled with opportunism and prevarication, Trump has remained uncharacteristically consistent through the years in one belief: his affection for tyrants.

Of course, many American leaders have cooperated with autocrats, terrorists, and dictators throughout the country’s history, and even praised individual ones. Ronald Reagan once memorably termed the contras, Nicaraguan rebels known for kidnapping and torturing civilians, “the moral equal of our Founding Fathers.” President Joe Biden has reneged on campaign promises to loosen America’s bonds with illiberal leaders in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere. But Trump is unique among presidents in expressing outright adoration for despots and authoritarians—not because they can benefit American interests despite their cruelty, but because, whatever impact they may have on American interests, these leaders have the virtue of being cruel. As Henry Hill says of the gangster Jimmy Conway in Goodfellas, Trump is “the kind of guy who root[s] for the bad guys in the movies.”

As president, Trump realized his ambitions to befriend tyrants, praising North Korea’s Kim Jong Un (“great strength economically”), Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (“he’s doing a very good job”), China’s Xi Jinping (“a very, very good man”), and, of course, Russia’s Vladimir Putin (“very smart”). He saved his insults for NATO and countries like Denmark. During his post-presidency, and now in his campaign to become president again this November, Trump has continued gushing about leaders who expend copious resources repressing the basic freedoms of their peoples. He has brandished their endorsements as qualifications for his reelection. In December, Trump said of Kim Jong Un: “He’s not so fond of this [Biden] administration, but he’s fond of me.” He was implying that voters should value the exceptional level of approval that he receives from someone overseeing maybe the world’s worst totalitarian state.

To be fair, this was a rare time when Trump was not lying: Many dictators, wannabe dictators, and assorted international miscreants are indeed fond of him. Some of them simply see a kindred spirit in him, understanding that, as he has admitted several times, he would himself like to be a dictator. Other autocrats grasp that he can be manipulated to their personal benefit. Still other tyrants understand that Trump’s assault on democracy in the United States makes their lives easier by weakening the leading liberal power, a country that represents freedom to many, even as it has sometimes undermined democratic forces around the world.

America’s connection with the global cause of freedom has always been rocky, like a celebrity relationship. Soon after the American Revolution demonstrated the power of anti-colonial republicanism, the young United States made efforts to snuff out the Haitian Revolution, lest the enslaved at home get any ideas. Ever since, the United States has pinballed between serving as an example of republicanism’s possibilities at home, acting in enlightened self-interest to support liberal forces abroad, and repressing huge numbers of people everywhere; between being the “well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all,” in John Quincy Adams’s imperishable words, and being “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world,” in Martin Luther King’s.

The foremost task of U.S. strategy is to secure the American system of government and the prosperity of its people, not to promote democracy elsewhere. As the journalist Walter Lippmann put it, the job of U.S. foreign policy is to act as a “shield of the republic.” But given our nation’s immense global importance, the actions that American leaders take (or fail to take) invariably have an impact on many, perhaps most, countries around the world. “You’re not going to export democracy, but at the same time, by creating an international environment that is favorable for authoritarianism or favorable for democracy—those things matter,” said Stonehill College professor Anna Ohanyan, author of several books on the Eurasian region.

Trump’s reelection campaign occurs at a vulnerable period for the cause of liberty. For nearly two decades, more countries have become less democratic every single year. According to the nonpartisan organization Freedom House, “authoritarians have gained ground during the past 17 years of global democratic decline.” In some cases during Biden’s tenure, such as Ukraine, the United States has played a vital role in supporting democratic forces that are resisting foreign tyranny. In other places, such as Israel and Egypt, the United States has provided instrumental aid to illiberal governments. But the mixed record at least offers reasons to believe that, in a second term, Biden could be pressured to take actions that strengthen a balance of power that favors freedom.

A second Trump administration, meanwhile, would embolden czars and caesars the world over and correspondingly diminish indigenous movements and institutions advocating for human rights and freedoms. Imagining another four years of Trump, five eminent European political analysts warned in February in Foreign Affairs that “the greatest risk Trump poses to Europe is to its values: multilateralism, care for the environment, the rule of law, and democracy itself. Through his rhetoric, Trump degrades the worth of these principles in public opinion.” The same is true on every continent. Trump may be the first post-democracy American president.

Given all that, here is a list of 11 tyrants and where they are likely to stand on the 2024 presidential contest, according to interviews with experts:

Vladimir Putin, Russia

For reasons that are still mysterious, Trump has uniquely exempted Russia from the lengthy roster of nations he insults and scapegoats for America’s woes, countries that include China, India, Germany, and Canada. He has lauded Putin in particular, variously calling him “a genius,” “tough,” “savvy,” and, perhaps accurately, “nicer than I am.” As president, Trump publicly certified Putin’s verbal assurances of his innocence, elevating them above the consensus of U.S. intelligence agencies, which declared that Russia had interfered in the 2016 presidential elections. And Trump’s first instinct after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 was to laud Putin’s supposed strategic smarts in launching the misbegotten war.

Despite Trump’s personal affection and friendly rhetoric for Putin, however, his administration was hostile to Russia in many ways, imposing sweeping sanctions in 2017, leaving a nuclear arms deal, and killing hundreds of Russian mercenaries in Syria. “I don’t think those were initiated by Trump, but he appointed people who were much harder on Russia than he was and didn’t do anything in particular to prevent them going down that course,” said Thomas Graham, a Russia expert at the Council on Foreign Relations. Kremlin hopes for a pliant United States under Trump were dashed and are not likely to be rekindled, according to Graham. In addition, the Russia-U.S. relationship might be so poisoned that it would be difficult for any president to repair it in the foreseeable future, even one, like Trump, oriented toward Putin.

And yet, Trump represents the wing of the Republican Party that is furious about the United States financing Ukrainian self-defense. Congress may prevent a cutoff of aid, but, at the very least, Trump’s return to the White House would boost Russian resolve and weaken Kyiv’s morale. Putin said in 2023 that he “cannot help but feel happy” about Trump’s promises to resolve the Russo-Ukrainian war “in 24 hours” if he becomes president again. Of course, as George Orwell said, the quickest way to end a war is to lose it. Putin may be salivating at the prospect of Trump managing to convince Congress to stop funding Ukrainian resistance, or even encouraging the Russian military to steamroll into Kyiv. Trump will undermine NATO, perhaps fatally wounding the alliance that has been essential to keeping Russia close to its post–Cold War borders.

Even if Russia does not hope to control Trump, having him in the public arena guarantees one thing: chaos. That at least offers something to Putin. The Kremlin generally prefers a predictable United States. “But they think political disarray in the United States, for a short period, would certainly prevent the United States from taking any coordinated, concerted effort that would undermine Russian interests,” Graham said.

Xi Jinping, China

During his run for the 2016 presidential election, Trump demonized China as no other major party leader had since the 1960s. But as was the case with his Russia policy, Trump’s actions in office oftentimes contradicted his words. Scott Kennedy, author of numerous reports on China at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, argues that Trump pursued three different approaches to China: a futile initial charm offensive vis-à-vis President Xi Jinping, followed by a modestly successful unilateral pressure campaign focused on the bilateral trade balance, and, lastly, a pandemic era defined by sanctions across the board simply meant to punish Beijing. “Sometimes people just sort of lump them all into one, but they were really pretty clearly demarcated over time,” Kennedy said. The tough talk and trade war were significant, but Trump simultaneously kneecapped key advantages the United States had over China by injuring America’s alliance system in Asia and sapping U.S. soft power. In addition, Trump’s catastrophic response to Covid and his incitement of the insurrection at the Capitol in January 2021 helped Xi portray the United States as an inept, declining power.

Biden, however, has upped the focus on China without offering any of the benefits Trump provided to Xi. He has cracked down on Beijing’s access to vital technologies, particularly advanced computer chips. He repeatedly pledged to support Taiwan with U.S. troops if China invaded the island. Most importantly perhaps, Biden fashioned a trilateral agreement with Japan and South Korea, coordinating a strategy to deter China.

It is unclear what a Trump second term would look like for China, except that it would probably be erratic and bombastic. “We don’t know whether we’ll get Trump the negotiator or Trump the hawk,” as Kennedy said. He said of Trump and Xi: “I think they both believe that they can manipulate and use the other.” However, Trump’s unpredictability means that China’s leaders may favor remaining with Biden, who, despite implementing severe measures to contain Beijing, has also de-escalated the inflammatory rhetoric, and frequently clarified that the competition between China and the United States should not deteriorate into violence anywhere. Chinese officials know that, whatever Biden’s flaws, he is the only one of the 2024 presidential candidates they can be sure won’t start a nuclear war impulsively. Diana Fu, a China specialist at the Brookings Institution, said, “To many in and outside of China, the elections already have a predetermined outcome: The United States will continue to view China as a competitor and a threat, regardless of who is in the White House.”

And yet Xi seems to understand that Trump undercuts sources of America’s appeal abroad and is personally vulnerable to wild emotional swings and flattery. “If Trump is reelected and pursues American isolationism, Beijing may actually stand to gain in terms of its influence in the Indo-Pacific and beyond,” said Fu. Trump may accede to China annexing Taiwan and claiming the South China Sea, hoping to sign a deal he imagines will bring him greatness. Perhaps he’ll praise Xi’s brutality toward the Uyghurs and suggest the United States should follow suit with our Muslim population.

Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel

Long before he became president, Joe Biden declared himself a Zionist and close friend of Israel. And indeed, now as president, Biden has given Netanyahu and his government, the most extremist in Israeli history, virtually unconditional support in its campaign against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. His administration has sent huge amounts of arms to Israel, protected the Jewish state from diplomatic opprobrium at the United Nations, and given even less acknowledgment to the Palestinian cause than had previous Democratic Presidents Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter. For all these reasons, Yousef Munayyer, head of the Palestine/Israel Program at the Arab Center Washington DC, said: “I don’t think Trump would have handled it much differently. But that doesn’t reflect well on Biden.”

Yet Israel’s longest-serving prime minister would clearly prefer to see Donald Trump return to the White House. For one thing, the Biden administration has warned Israel against initiating a wider regional war and insisted that a Palestinian state must one day materialize, opposing discussions in Netanyahu’s government in both cases. More grandly, Netanyahu sees a similar spirit in Trump and has long had connections to the GOP. “Netanyahu is something of a patron saint in the Republican Party,” as Munayyer said. Since Trump left office, he has called Netanyahu disloyal and chided him for being unprepared for Hamas’s October 7 massacre inside Israel. But, despite these comments, Trump would likely permit Israel to unleash its formidable military capabilities beyond its borders, deeper into Lebanon, Syria, and perhaps Iran. The Palestinians would suffer even more, as Israel’s hard-liners would understand they can kill civilians en masse without retribution and will openly foreclose any possibility of a state for them, ever. After all, while president, Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, rejecting the consensus of other world leaders. Finally, his most intense domestic endorsements come from evangelical Christians who are supportive for religious reasons of the most extremist parties of Israel and are often hostile to Muslims, and he may seek to reward their backing.

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt

In 2019, President Trump was waiting for a meeting with Egypt’s president. “Where’s my favorite dictator?” he asked aloud. The Wall Street Journal suggested that, “even if lighthearted, Mr. Trump’s quip drew attention to an uncomfortable facet of the U.S.-Egypt relationship.” But in fact, Trump was conveying admiration, not discomfort, for el-Sisi’s authoritarianism. “Egypt has made tremendous progress under a great leader’s leadership,” Trump said on another occasion, although, of course, no such progress had been made. This rhetoric marked a shift from President Barack Obama, who had condemned el-Sisi on several occasions, withholding military aid for a time after he came to power in a coup in 2011.

Despite saying there would be “no more blank checks for Trump’s ‘favorite dictator,’” Biden has done the same two-step dance as Obama, approving the sale of nearly $200 million in missiles to Egypt while criticizing the government’s human rights record. Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip made Egypt more important to the United States than it had been, as the country mediates between Israel and Hamas. Given this extra incentive, it is difficult to imagine Biden taking a harder line against Egypt in a second term. Still, el-Sisi would opt for Trump to become president, given their shared distaste for civil liberties and democracy. Steven Heydemann, professor of Middle East studies at Smith College, said, “What would be significant, and I think it would be something we might expect from a Trump administration, would be to signal much more vocally and much more visibly its support for Sisi personally, its support for his regime.” That could push el-Sisi to transform Egypt into something more totalitarian, ending any potential opposition or dissent from emerging.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey

Erdoğan has overseen Turkey during its transition from a democratic-leaning state to an authoritarian, Islamist-influenced one. As president, Trump acceded to Turkish expansionism, as the country sent proxy forces to fight in Syria, met with members of Hamas, and intervened in Libya as a way of asserting power in the region. Congress blocked arms sales to Turkey for two years, which frustrated the Trump administration. Like other unsavory characters trying to get on his good side, Erdoğan savvily played to Trump’s bottomless capacity for vanity, leading Trump to once brag that world leaders he left unnamed had asked him to try to talk to Erdoğan on their behalf, since Trump was the only person he respected. Trump once told an American whom Turkey had locked up dubiously for two years that, to him, “President Erdoğan was very good.”

As a presidential candidate in 2020, conversely, Biden called Erdoğan an autocrat (a negative designation in Biden’s lexicon, refreshingly) and urged support for domestic opposition to his regime, leading the Turkish government to say the former vice president’s notions were “based on pure ignorance, arrogance, and hypocrisy.” Since taking office, Biden has kept Erdoğan at a distance, affirming that the Ottomans carried out a genocide against the Armenians early in the twentieth century, a historical fact the Turks have long denied. Biden also conspicuously excluded Erdoğan from his ill-fated Summit for Democracy, although the president in January urged Congress to approve the sale of fighter jets to Turkey to reward the nation for agreeing to let Sweden join NATO.

Turkey’s president would love a photo op with the U.S. president to enhance his credibility as a regional leader. Asli Aydintaşbaş, visiting fellow specializing in Turkey at the Brookings Institution, said, “Erdoğan would probably rejoice at the prospect of a second Trump administration.” Firstly, by embracing the Turkish leader, Trump would enhance his domestic profile as an international mover and shaker. “He hasn’t been able to demonstrate that to the public over the past four years, in part because Western European governments and the Biden administration have held him at arm’s length,” said Aydintaşbaş. Any concerns about Turkey’s democratic regression would be scorned by Trump, who would surely once again be vulnerable to ridiculous compliments from ill-motivated suitors. Erdoğan might also like to see Trump remove U.S. forces from Syria and Iraq and could attempt to fill the void with personnel funded by Turkey. Stonehill College professor Anna Ohanyan said “Erdoğan would benefit tremendously” from a Trump presidential revival. “He got a lot out of Trump.” Next time around, he would get even more, permitting him to unleash violence on the Kurds and end Turkey’s democratic experiment for a generation.

Viktor Orbán, Hungary

Of all leaders in the world, Hungary’s president is perhaps the most open about his preference in the 2024 election. Just as in 2016 and 2020, Orbán is loudly proclaiming his desire to see Donald Trump as U.S. commander in chief. “Trump is the man who can save the Western world,” he told media personality Tucker Carlson in August. “Call back Trump!” As a global symbol of white male grievance working in alliance with Christian conservatives, Trump naturally appeals to Hungary’s leader, whom right-wing agitator Stephen Bannon once called “Trump before Trump.” To reward Orbán’s success in undermining Hungary’s independent judiciary and liberal freedoms, Trump invited Orbán for an Oval Office visit in 2019, which he had been denied since 1998. Biden, meanwhile, left Orbán out of his Summit for Democracy, leaving Hungary as the only country from the European Union unrepresented there. That led Budapest to block the E.U.’s formal participation in the summit.

As the head of a quasi-free state that he is leading in an authoritarian direction, Orbán has long been an inspiration for American conservatives and has looked to them, in turn, for legitimacy and support. “Orbán and Trump have a bromance going on,” said Kim Lane Scheppele, an expert on Hungary at Princeton University. “There are lots of people who go back and forth between that Trump orbit or Orbán orbit. So, it’s not just that they’re kind of blowing kisses from a distance, but that they actually have people who work together, on a daily basis.”

In 2022, Trump, out of office, said he wished for Orbán to triumph in upcoming elections, calling him a “strong leader” who has “done a powerful and wonderful job in protecting Hungary, stopping illegal immigration, creating jobs, trade, and should be allowed to continue to do so.” With Trump in office, Orbán will solidify the authoritarian takeover of Hungary’s once-promising liberal era.

Bashar al-Assad, Syria

Bashar al-Assad, responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of citizens of his own country, had high hopes for Donald Trump when he assumed the presidency in 2017. He imagined that Trump would be a “natural ally” in the fight against terrorism and rationalized the president’s Muslim travel ban as an anti-terrorism measure. And indeed, Trump reduced the presence of American troops in Syria, which no doubt met with Assad’s approval. But after Assad used chemical weapons to gas more than 100 people to death, Trump ordered that 59 missiles strike Syrian airfields, mused about assassinating Assad, and implemented sanctions against his cronies.

The Biden administration had continued the hostile policy against Syria and discouraged the Arab League from bringing Damascus back into the organization (the league did so anyway). “One of the interesting features of [U.S.] Syria policy has been its continuity, I think, across administrations,” said Steven Heydemann. Even so, if he has a favorite, Assad is likely eager to see Trump take the White House again, since Trump may wish to further remove American troops from the Middle East. Said Heydemann: “That would be seen as a significant win by the Assad regime, but I don’t think in and of itself that is sufficient to give the Assad regime a sense that its future relationship with the United States or its broader position in terms of its pariah status in the international system might be affected by the outcome of the election this November.” What Assad might get is more open support from Russia and Turkey.

Kim Jong Un, North Korea

Trump in office oscillated between thoughtless threats to “totally destroy” North Korea and equally hasty maneuvers to secure some pact by being the first U.S. president to visit the isolated country, and between calling leader Kim Jong Un “a maniac” and valorizing him as “very honorable.” Most bizarrely, after receiving a letter from Kim in 2019, Trump said, “We fell in love.” He clearly prizes the ostentatious displays of reverence North Korea’s leader receives, saying that Kim “speaks, and his people sit up at attention. I want my people to do the same.” (Trump later lied and said he was being sarcastic in that comment.)

In December 2023, Politico reported that Trump is considering a realistic approach to North Korea in a second term. Apparently, he would offer Kim a chance to get sanctions lifted and U.S. acquiescence to North Korea’s nuclear program if the dictator refrained from adding further weaponry to his arsenal. Toby Dalton, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said that it’s possible Trump would go further, declaring that he was pulling U.S. troops out of South Korea and Japan, effectively ending the alliances. Kim “could assume there could be a huge change in U.S. policy,” Dalton said, something that offers both risks and rewards for North Korea.

However, Trump’s ambitions might get constrained by his advisers and his administration’s bureaucracy. That is essentially what occurred in his first term. Refining the details of international agreements is beyond his attention span, and his incessant need for obsequiousness means that Kim could rupture relations simply by not flattering Trump’s ego sufficiently. “I’m not sure that Kim Jong Un is as fascinated with Donald Trump as the other way around,” said Dalton.

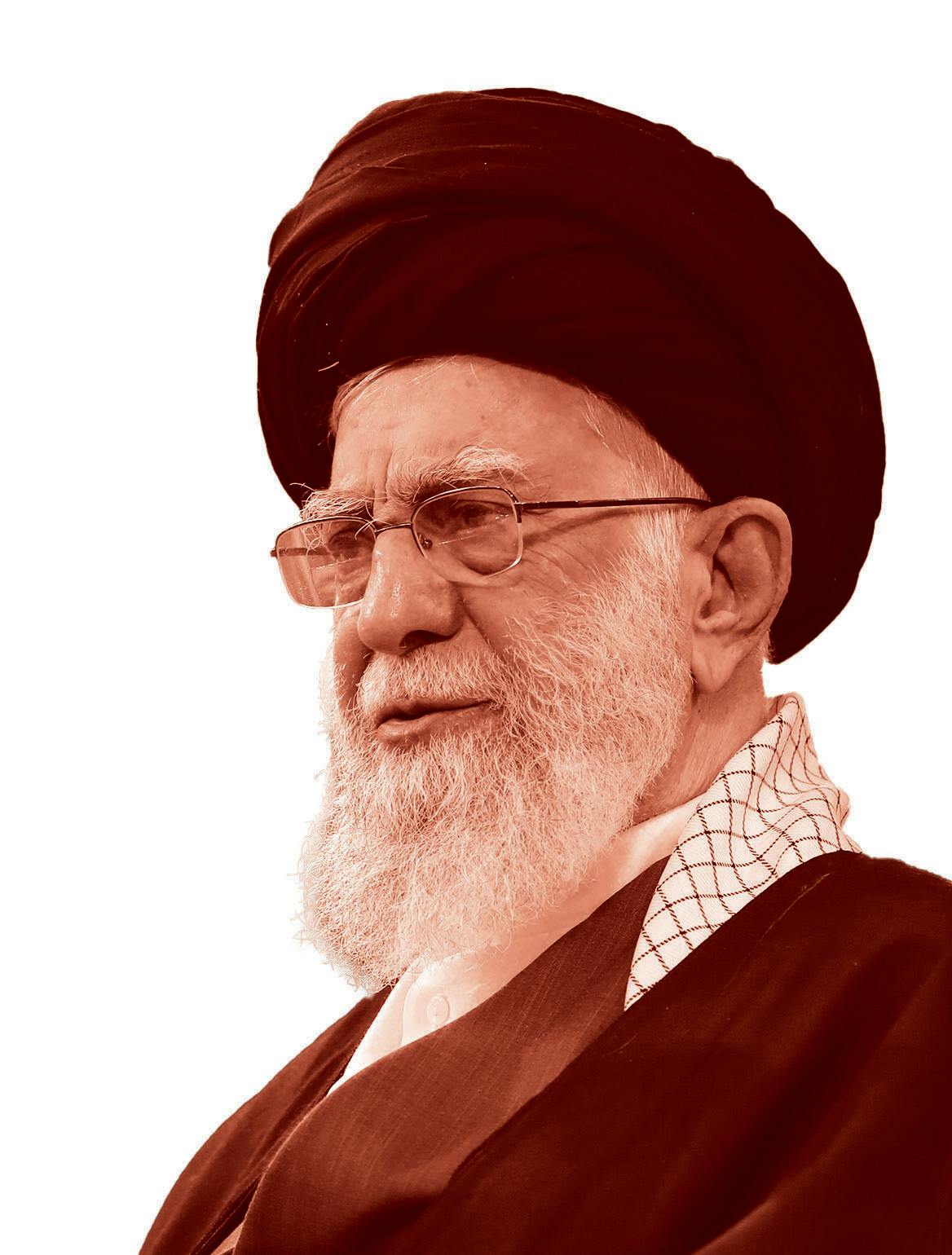

Ali Khamenei, Iran

Unlike many leaders on this list, Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, presides over a government that is deeply divided over whether to pursue better relations with the United States under any president. That was true even when Iran signed a deal concerning its nuclear enrichment program with President Obama and its allies in 2015, as mutual suspicions going back decades between the two sides remained severe. When Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States from the agreement in 2018 and imposed new sanctions on Khamenei and others, he not only reneged on a deal that was deeply favorable to U.S. interests—Iran revived its nuclear program in 2020—but confirmed the sentiments of the wing in Tehran that sees Washington as implacably hostile to the Islamic Republic.

Sadly, Biden, as president, said the United States would rejoin the deal only if Iran took the first step of shuttering its nuclear enrichment program. That didn’t happen, and the agreement was not revived. In January 2024, Iran-backed militias killed three U.S. service members near the Jordan-Syrian border, one of 165 attacks (as of early February) targeting American troops in the Middle East since the Israel-Hamas war began.

Even though relations between Iran and the United States are horrible, they could be worse, as Republican senators such as South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham and Arkansas’s Tom Cotton are angling for direct strikes on Tehran. As president, Trump reportedly called off an attack on Iran, but his impulsivity and need to appear tough make his future actions unpredictable, given his perennial need to appear militaristic. Barbara Slavin, an Iran specialist at the Stimson Center, said, “Hard-liners in Iran would prefer Trump, because he will drag down the U.S. reputation internationally even more and make the U.S. more isolated.” Conversely, “More reform-minded Iranians would prefer Biden, who, in a second term, might be more amenable to compromise, as second-term Democratic presidents have tended to be.”

Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan is one of those countries that receive little attention in the United States because it is small and arguably peripheral to American interests but is affected by decisions taken by Washington. President Ilham Aliyev has ruled the country for more than 20 years, succeeding his father, Heydar Aliyev. The leader is allied with Turkey and Russia and menaces neighboring Armenia. The Obama administration sporadically called out Aliyev’s many human rights abuses and played an important role in negotiations between Azerbaijan and neighboring Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed region that has been a flashpoint for war for decades.

Trump has a long history with Azerbaijan. In 2012, his company signed deals with a notoriously corrupt family there to build a tower in Baku, the capital, possibly in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a law prohibiting U.S. companies from benefiting from foreign corruption. A New Yorker report called it “Trump’s worst deal.” While he was president, the United States was conspicuously absent from talks that eventually led to a peace agreement concerning Nagorno-Karabakh. Trump did not even grant ambassador status to his representative in the region, signaling his administration’s detachment from the conflict. “The impact of his foreign policy in the South Caucasus, especially on Armenia and Azerbaijan, was just devastating,” said Ohanyan. In September 2023, Aliyev attacked Nagorno-Karabakh again, launching an ethnic cleansing campaign, and U.S. officials have affirmed support for the region’s Armenian population.

If Trump comes to power again, he may again reduce the U.S. presence in negotiations, depriving Armenia of important leverage and greenlighting Azerbaijan’s takeover. Aliyev “is banking” on Trump winning, said Ohanyan, adding that his position at the negotiation table has already hardened in anticipation of Trump’s return. “Aliyev would benefit tremendously if Trump was elected.”

Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia

Republican Presidents have usually been closer to Saudi Arabia than Democratic presidents, and Trump was no exception. Whereas Obama had publicly derided the Saudis and suspended some arms sales, Trump embraced them on his first foreign trip as president and resumed the weapons sales. He called them a great ally soon after the CIA concluded that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had ordered the murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey. He vetoed congressional attempts to end support for the brutal Saudi-led war in Yemen and to halt arms sales for the war. Madawi Al-Rasheed, professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, said of the crown prince and Trump: “They share a lot in common, especially personality-wise.” She added, “They get on very well, because it’s transactional. They only understand power and interest and money.” Trump’s relationship with Saudi Arabia didn’t even conclude at the end of his term: Soon after Trump left office, bin Salman rewarded his friend by investing billions of dollars in a private equity firm headed by Trump’s corrupt son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

Among the most disappointing areas of U.S. foreign policy under Biden has been Saudi Arabia. He has kept intact the desert nation as the top recipient of U.S. military equipment and flirted with offering it security guarantees. But a Trump revival would advance these deepening ties further. Saudi Arabia wouldn’t have to worry about any pressure on human rights in Yemen or anywhere else. Steven Heydemann said, “Among the most influential states in the Middle East, including in the gulf, the [United Arab Emirates], Saudi Arabia, even Qatar, there seems to be a sense that it would be easier for them to work with Trump, with the Trump administration, than with the Biden administration.”

Donald Trump would be disastrous for the cause of freedom in the United States and in the world. For one thing, the country’s ability to model itself as a functioning, just democracy, always its best and most underrated asset in foreign affairs, would be weakened beyond its already dismal state. Second, Trump appeals to authoritarian populists, corrupt kleptocrats, and white nationalists in ways unlike any other American leader, and his return to the presidency would energize these villains, giving them free rein to crush dissidents, defiance, and democracy. Third, Trump would take a hammer to America’s alliances with other democratic countries, weakening them individually and collectively. Finally, Trump may simply shift U.S. foreign policy in the direction of the dictators and autocrats he so admires, with little regard for American interests. In a long life of lying and larceny, Trump’s valentines to strongmen and tormentors have been among his few reliable and truthful statements.

America’s domestic problems are severe and numerous, and it would be understandable if voters concentrated on matters at home. But the Biden-Trump match carries high global stakes, and not only for Americans. Internationalist-minded conservatives may wish to consider the fate of freedom around the world in casting their vote. And liberals and leftists who imagine that Biden’s blunders cannot be exceeded in foreign affairs, even in the Middle East, are suffering from a severe failure of imagination. As Shakespeare put it in King Lear, “And worse I may be yet: the worst is not so long as we can say, ‘This is the worst.’”