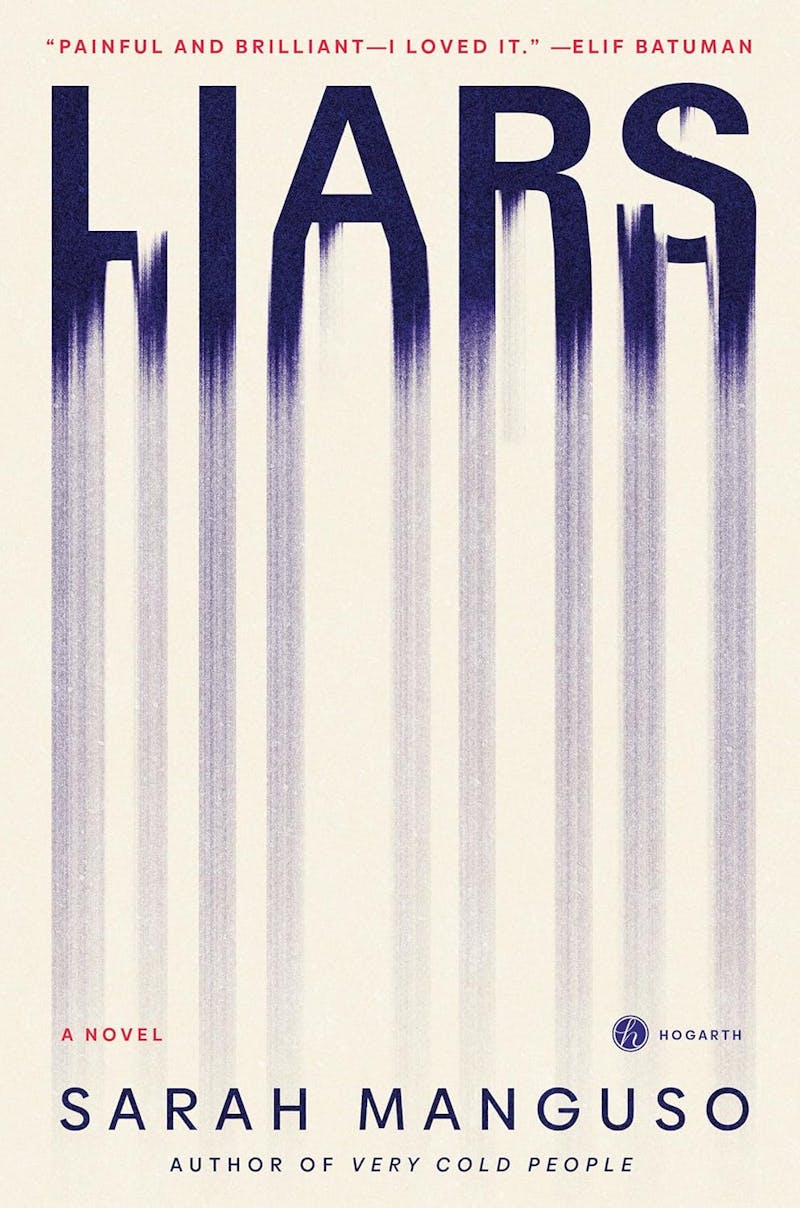

On the first page of Sarah Manguso’s electrifying, devastating

novel Liars, the narrator warns her

reader that she has “got enmeshed in a story that’s already been told ten

billion times.” Liars follows the 15-year

relationship between Jane and John (the names tip us off that we may be dealing

with archetypes, waiting to be disturbed), from their brief courtship to the

end of their tormented, tumultuous marriage. But as the narrator’s opening

self-consciousness hints, Liars is

also a metanarrative of sorts: a novel about how to evoke the systemic ills of

heterosexuality, marriage, and gender, even and especially when we experience

our position within those institutions in idiosyncratic and individual terms.

Late in the book, Jane notes that she has begun “to understand what a story is. It’s a manipulation. It’s a way of containing unmanageable chaos.” The notion that narrative is a partial, discriminating act, selectively imposing order onto the disorder of its raw material, is not a new one, but it has particular significance in the context of misogyny and its myriad forms of oppression and violence. Jane’s fury at John—at his obliviousness, his abysmal business decisions, his inability to participate in domestic labor—drives the novel and limits the omniscience of its perspective. This is as much the result of Jane’s status as an unreliable narrator as it is a reflection of how near impossible it can be, from the standpoint of our intimate lives, to distinguish personal failures from deep social structures. What makes a problem the consequence of a wider structure versus an expression of individual pathology? Is a husband’s disregard for his wife’s career an example of his own selfishness, or does he act as a conduit for the economic and social forces that still designate domestic labor as a woman’s domain? How do we trace the intricate, infinite causal lines between socially entrenched attitudes and our private relationships? This is the wild, impossible “chaos” whose attempt at containment Liars narrates.

If the story of a troubled marriage has been told ten billion times already, why tell it again? The cultural terrain of “female rage,” to which on its surface Liars might seem to belong, is by now well wrought. By its logic, John’s misdeeds met by Jane’s inevitably and rightly furious response together comprise the sum of the narrative in which they exist. When Jane and John first meet, they are both working artists: Jane a writer and John a visual artist. In Jane’s eyes, the forfeiture of her career for John’s happens gradually. Early on, during their first year together, John encourages Jane to apply to a fellowship that accepts two applicants each cycle, thinking they might both win; Jane does and John doesn’t. “Affectless,” John tells Jane that he “wants to be as successful in my field as you are in yours.” “He didn’t want to be the unsuccessful partner of the successful person,” he explains. “Then he apologized and said that he’d just wanted to be honest.” Jane’s comment: “It was brave and considerate to tell me.” This type of retelling is characteristic, tonally, for Liars: deadpan and dryly witty. Rather than editorialize, Manguso lets John’s wrongs speak for themselves. “He couldn’t afford a ring,” Jane notes about her and John’s engagement, but “then he had six more shirts made” for himself. He asks his mother for money, then “ordered a two hundred dollar lamp.” Anecdotes like these accumulate and reinforce each other; they constitute a great part of the novel’s content, and are further compounded by its form, a listlike series of paragraphs visually separated from each other on the page.

Written this way, the novel gathers moment after moment of Jane and John’s relationship and its numerous asymmetries; like a list, it groups according to a larger organizing principle without offering connective tissue between, say, a paragraph about Jane, “sobbing and stammering” when she tells John how unhappy she’s been since a recent move for his job, and how, one day: “By noon I’d showered, tidied the house of John’s shoes and clothes, put away laundry, swept the floor, watered the garden, moved boxes to the garage, cooked breakfast, eaten, done the dishes, taken out the recycling, handled correspondence, and made the bed. John had gotten up and taken a shit.” (Fleeting moments like these also concretize the diminishment of Jane’s creative labor as it is sacrificed to her domestic labor, one of her fury’s main sources.) Although these blocks do further a linear, chronological narrative, the small jumps from one to the next mean we experience each moment serially. This form is well suited to an emotion like rage, whose logic similarly amasses, intensifies, and gradually fortifies itself.

Indeed, in Liars, Manguso has offered us something like an aesthetics of rage. The novel’s very form—raw, ragged, one-sided—adopts qualities of the feeling, filtering and inflecting the content within it. And yet crucially for Liars, this also means engaging with the limitations of rage as a narrative principle—with the fact that it is at its core a mode of distortion. It fixates, amplifies, and disguises; it overlooks, misrecognizes, and repeats itself. It makes lapses of judgment, and it remakes the objects of its attention in its own image. Jane variously reveals her own crimes, shortcomings, and harms, but obliquely and tangentially; they are, after all, not the object of her ire. In response to John imperfectly tidying the kitchen, Jane passive aggressively “rage cleans.” Sporadically, she attempts to communicate ways to improve their relationship to John through secondhand therapy-speak, but she just as quickly abandons those efforts. She has outsize responses to small, thoughtless mistakes John makes, “exploding” at him when he buys the wrong bread while grocery shopping. At some point after she gives birth to their son, when John attempts to defend himself during an argument, Jane bitingly mocks his insistence that things are not his fault. “They never are” becomes her vicious, seething refrain. In yet other moments, the novel’s self-consciousness of its intrinsic blind spots materializes through Jane’s ironically sweeping claims about gender relations. “Maybe the trouble was simply that men hate women,” Jane provocatively, imperfectly offers.

These moments, however quietly they slip into Jane’s account, persist nonetheless. Their inclusion enriches the novel and the political questions at its core, for the stakes are not only aesthetic. To eagerly embrace female rage as an analytic and narrative device is not only to put forth a shallow view of human relations, in which only one member of a long-standing intimate partnership is ever at fault. It is also to endorse a superficial understanding of gendered inequalities that, at worst, risks performing a sort of gender essentialism. By this logic, women are innately, naturally angry at male failures, uncannily echoing hysteria’s rightly outdated vocabulary. At best, the conceit patronizes and placates in its vague, imprecise, passing acknowledgment of gendered harms—which narratives of female rage typically put in interpersonal terms as opposed to, say, exploring structural misogyny’s real economic base.

Liars shares its serializing form with Manguso’s first novel, Very Cold People, which also takes gendered oppression and the material conditions that scaffold it as its theme. In that haunting, bleak book, Manguso follows a young girl, Ruthie, from childhood to adulthood as she grows up in a small Massachusetts town. There, sexual violence, in a darkly diverse array of forms, affects one after another of Ruthie’s acquaintances and friends; the novel tracks Ruthie’s evolving consciousness, as she ages, of this pervasive and routine violence. Very Cold People is, despairingly, a novel about how violence seems almost to exist in the very air we breathe: how violence that is found seemingly everywhere starts to feel like it’s nowhere in particular at all. Both novels showcase Manguso’s interest in the levels at which gendered harm operates, whether those be interpersonal or systemic. In Very Cold People, though, she attends specifically to how vulnerability to sexual violence is born of poverty, dispossession, and other social precarities. If contemporary mainstream feminism tends to concern itself with measurable outcomes—institutional and legal victories, for instance—then Very Cold People is a novel about how to narrate and atmospherically render gendered violence when the promise of any such outcome appears nonexistent.

As in Very Cold People, in Liars, Manguso displays a painstaking attention to materiality, providing a meticulous account of a single relationship and both the intimate and social forces that eventually infect it. Manguso pays a kaleidoscopic attention to the negations, justifications, and denials that texture the way we behave with one another, and the way we describe that behavior to ourselves. Through and against the rage that characterizes so much of Liars, then, is a counterimpulse to taxonomize, explicate, and contextualize. After breaking a piece of one of John’s sculptures and lying to him about it, Jane admits that “it felt like getting even with the harm he’d done me.” Manguso’s eye is attuned to the silent justifications that beget injury, that rationalize minute transgressions within longer chains of events.

Although such admissions undermine a simpler narrative in which John is the only villain, they are essential not only to a more textured account of a marriage but to the clarity that Jane seeks, despite and through her anger. When she was young, she says close to the novel’s end, she swore she’d never marry: “I’d understood that commitment was a trap that closed off otherwise accessible exit routes. Then I had therapy for ten years and learned that commitment was a gift, the ability to give your heart to another.” Two possibilities appear. She can frame everything about her marriage’s failures as a straightforward expression of society’s ills against women. Or she can understand her marriage’s shortcomings in a political vacuum, as solely the failed commitment between two flawed individuals. To fasten herself to only one of the two options would not only make for a simpler narrative but for an immediately easier emotional life. But it would also tie her to a fantasy of life whose suppressions—whose lies—will keep painfully resurfacing, whether as more of the resentment that animates Liars or as Jane’s lagging, latent sense that her anger’s selective gaze distorts the more complex truths she ultimately seeks.

Ultimately, Liars stages Jane’s growing consciousness of these fantasies’ limitations, which is also to say that the novel argues for the necessity of moving beyond the simplistic, reductive understandings of gender, marriage, and heterosexuality that have become so freely available to us. As the book closes, Jane grasps that her rage is a beginning, not an end. It is an entry into comprehending a complex, pained chapter in her life rather than that chapter’s final verdict. “Together,” Jane allows, “the two truths were heavier than they were separately.” Even so, she “held tight to them both.”