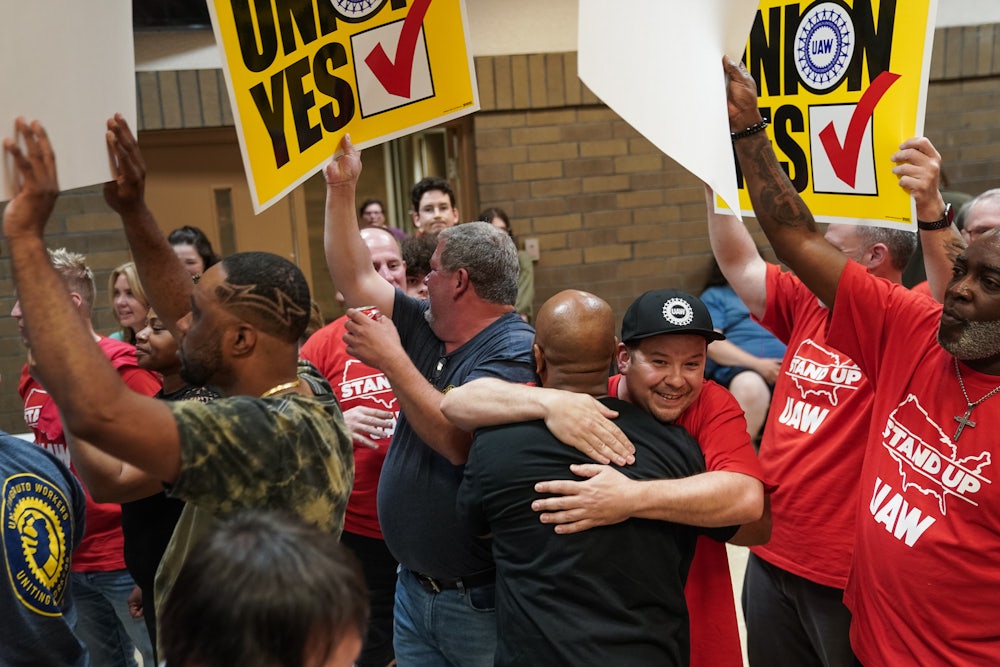

Angel Gomez, a second-shift underbody mechanic at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, was on the line when United Auto Workers won the factory union election. “I heard hollering,” said Gomez, as the news broke through the shop floor on Thursday, April 18. “There were people who’d been trying to do this for 14 years, they’ve been putting in the work through all these failed elections, and finally they got it. It was a good feeling.”

Renee Berry, 58 years old and a veteran of those two failed elections, was even more ecstatic. Apologizing over and over again on the phone for being so emotional, she told me the ballot count was agonizingly slow: yes, no, no, yes, yes. “I almost had an anxiety attack,” she said. “We put our blood, sweat, and tears in this plant.”

The Volkswagen plant had become a litmus test for the South. After UAW’s union campaigns at the plant were defeated in 2014 and 2019, the popular adage was that labor just couldn’t win here. The country’s media outlets of record united to declare the South a resource pit, a place where labor goes to die.

And it’s true that states here are right-to-work, where the power of unions is severely curtailed by legal barriers to organizing and wages overall are far lower than the national average. But, as this election shows, the South is home to an energetic homegrown labor movement that’s patient and insistent in the face of a hostile political climate. That, combined with an injection of federal investment in renewable energy industry, is pushing the region toward a very different trajectory than the one imagined by conservative politicians who have opposed these developments.

Corporations, and the incredibly wealthy people who run them, have become Republicans’ biggest donors, swaying even more moderate politicians into virulent anti-unionism. That’s trickled down to local politics in places like Chattanooga, where many people lacked unionized family members or much context for what union membership might mean. “It was just a lot of people who are ambivalent, and just seemed like, I’m not sure, a lot of these guys, you really just needed to give them just a little bit of information, like a little bit of like, ‘Hey, this is what could be possible,’” said Zach Costello, a worker who was on the organizing committee. It was often easier to convince people like Berry, whose dad was a union steelworker: She knew it meant health care, a pension, higher wages, and job security. They and Gomez fanned the embers, despite Southern politicians over the past few decades doing their best to stamp the spark of the labor movement out.

The Volkswagen plant is the first new auto industry union in the South in 80 years, and the only union plant owned by a foreign automaker. “In the nineties, governors began trying to entice foreign auto plants to come to the South,” said Stephen Silvia, a labor economist at American University. “They told auto producers that wages are lower, taxes are lower, land is cheaper, and we cultivate a nonunion environment.”

It all began when Tennessee offered Nissan generous incentives to establish a plant in the community of Smyrna. Nissan became the first foothold in a wave of industry relocation to the South, and amongst the state’s owning class, a sign of incoming prosperity. “We’re all gonna be rich!” exclaimed the mayor of Smyrna at the time, according to an account in the Journal of Southern History.

In 1989, UAW’s attempts to organize the Nissan plant lost by a two-to-one margin. The companies’ union-busting playbook—frightening ads that threatened the plant’s closure, captive audience meetings, rhetoric about losing jobs, and offers of competitive pay should the union lose—became the playbook for anti-union campaigns across the region ever since. As unions lost, the auto industry’s landscape tilted southward, meaning that about half of autoworkers now work in nonunion plants, which are mostly located in the Southeast. Before that time, nearly all autoworkers belonged to a union. Auto manufacturers located themselves in rural areas, often establishing racist hiring practices to keep solidarity out of the shop floor. Other industries trickled into the region, too—aviation, tech, chemical manufacturing, and paper products, just to name a few. All made their homes in various states where business came cheap and easy.

Climate regulations and the Inflation Reduction Act’s generous incentives are now stimulating electric vehicle manufacturing. Despite the Biden administration’s pro-labor economic agenda, IRA funding—and thus billions of dollars in public and private investment—has largely gone to areas with low union density, spurring worries among autoworkers that the E.V. shift could create a second tier of lower-paid, nonunion workers spearheading the transition to electric vehicles, working in dangerous conditions with flammable elements like lithium.

In 2022, Volkswagen broke ground on E.V. production and assembly; the same year, the Mercedes plant in Tuscaloosa, Alabama—UAW’s next battle, organizers tell me—began manufacturing an electric SUV. In the most recent union contract between UAW and the Big Three automakers, General Motors and Stellantis agreed to allow joint-venture E.V. manufacturing plants under the union umbrella, and now, Tennessee may be the next step.

Since the beginning conversations about reducing dependence on fossil fuels—a necessary transition that nonetheless could have deleterious impacts on workers across steel, coal, oil, auto, and building trades industries—workers have demanded a “just transition”: an energy transition that prevents as much of the workforce as possible from being dislocated, allows for training and opportunity, and provides jobs equal to or better than the ones that came before. Environmental organizations have taken up the demand, too, seeing that a united front for labor rights and environmental justice is more powerful than keeping the two at loggerheads, as right-wing politicians might prefer. A just transition is what workers in the South are demanding as the IRA funds flood in.

“We’re seeing a bunch of E.V. manufacturers come here,” said Michael Adriaanse, “and they should be union.” Adriaanse organizes with the Blue Oval Good Neighbors Committee. In rural, working-class Black communities in west Tennessee, this labor and community coalition is mobilizing to bargain with Blue Oval City, a Ford joint-venture electric vehicle plant that’s the recipient of the largest public investment the state of Tennessee has ever made, with an added $9.2 billion in funding from the Department of Energy. The VW victory has given workers hope for their efforts to negotiate good jobs and community benefits with the E.V. industry, he added. But it’s going to be hard-won.

“Anti-union sentiment across the country is virulent, and laws across the country don’t support unionization,” said Vonda McDaniel, who serves as a part of the Blue Oval coalition and is president of the Middle Tennessee Central Labor Council. Lawmakers in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama passed bills just this year and last year barring state incentives to companies that voluntarily recognize unions. In 2022, Tennessee enshrined right-to-work into its constitution. The prospect of this election had Southern governors running scared, so much so that the governors of Tennessee, Texas, South Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia wrote a joint public condemnation of the union drive. In Alabama, which boasts the seventh-highest poverty rate in the country, Governor Kay Ivey lambasted UAW, saying that “the Alabama model for economic success is under attack.” Research has shown that any economic growth in right-to-work states tends to benefit the already-wealthy.

In its previous attempts to organize Volkswagen, the UAW attempted a top-down strategy, where they tried to simply persuade Volkswagen to recognize the union. The UAW employed a different strategy this time, a bottom-up strategy that truly involved deep organizing in the plant. “This has to be personal, person to person, door to door,” McDaniel said.

The simple power of conversations worked for Zach Costello, who found that once people started talking about their conditions, they started flipping themselves more than he really flipped them, often across partisan lines. “You really saw a lot of people you would expect, because of their political leanings, to not really be pro-union,” he said. “But people are ready to throw out culture war crap, when they’re talking about real things that affect them.”

McDaniel now hopes national unions—many of which have been wary of investing resources in the region—see the success of this strategy. Currently, state-level politics in the South mean many unions tend to write it off, refusing to engage their resources in what they have seen as a losing battle.

Outside the automotive industry, other regional rank-and-file workers and labor organizers see these victories reinvigorating their own long-term struggles for economic and racial justice. While Tennessee is still ranked the thirteenth-lowest state in terms of union representation, its union membership is the fastest-growing in the country, across all job sectors. UAW’s changing strategy and priorities certainly made the win possible, but so, too, did the genuine exuberance and support of the statewide and Southern labor movement, which has been chipping away at poor working conditions, workplace inequality, and depressed wages for 200 years—through the end of slavery, through miners’ rebellions and textile strikes, through Black sharecroppers’ uprisings, and the Memphis garbage collectors’ strike that saw Martin Luther King’s final speech. Workers in Tennessee say they’ve been working for this kind of breakthrough.

“Something feels different in Tennessee,” said Bobbi Lyn Negrón, a public school teacher and member of the Metropolitan Nashville Educators Association, which won a fight against school privatization only this week. “But we still have workers across the South that have been resisting.” Negrón listed a few fights off the top of her head: Memphis fragrance factory workers who’ve been on strike; an active campus workers’ union in the eastern part of the state that has won repeated graduate stipend raises. Amid a dispiritingly anti-labor state political climate, this feels like a moment of true possibility. “We have a saying in Spanish, ‘like candela’,” Negrón said, “meaning the fire in us is going to ignite.”