Of the many lessons to be drawn from the last decades’ battles over climate policy, one is that yelling at people about data doesn’t tend to make them do something about it. Scientists have produced a steady drumbeat of ever-scarier numbers since the 1980s, detailing the horrors to expect as temperatures rise. Many of those horrors are coming to life; July may well have been the hottest month earth has seen in 120,000 years.

Despite this crush of evidence and growing public awareness, governments have been painfully slow to respond. Even if all the pledges countries have made to reduce emissions under the Paris Climate Agreement are fully realized, the world would still be on track to warm by 2.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

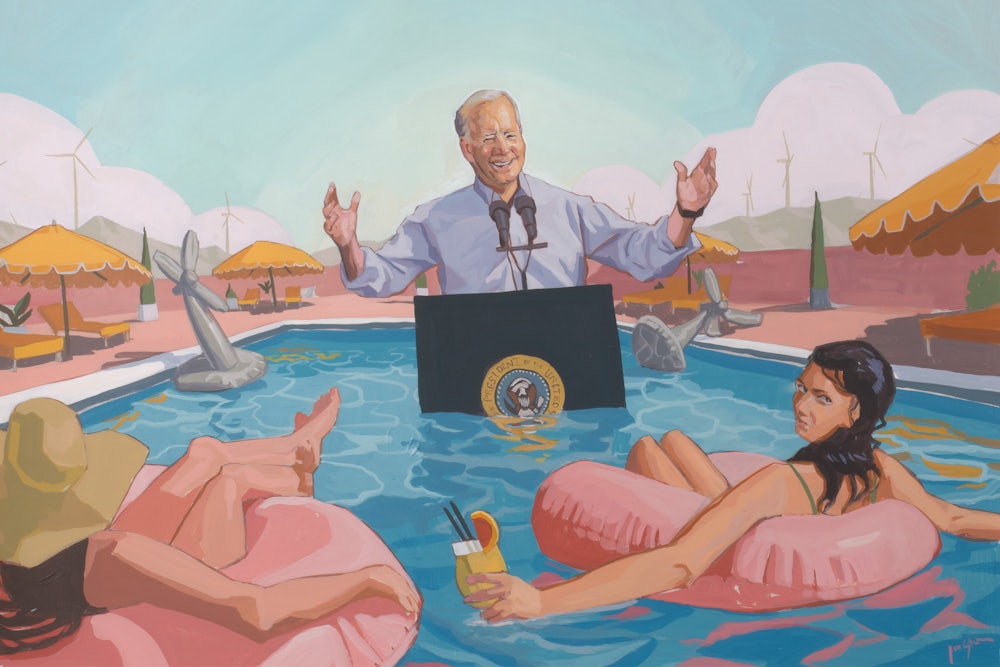

Out of these politically and socially stagnant circumstances, and a razor-thin congressional majority, the Biden administration last year managed to grind out a remarkable win: this country’s first-ever large-scale green spending bill. The numbers show that it’s spurring the kinds of investment its authors hoped it would. But a year on from the signing of the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, Biden hasn’t reaped much political clout from making the economy sing or passing America’s biggest chunk of spending on climate priorities to date.

A Washington Post–University of Maryland poll conducted in mid-July found that 57 percent of Americans disapprove of his handling of climate change; 71 percent heard “a little” or “nothing at all” about the IRA. At least two-thirds are broadly unfamiliar with its component parts, including electric vehicle subsidies and tax credits for wind turbine and solar panel manufacturing.

Over the last few weeks, the White House has joined left-of-center economists (and pundits and politicians) in fretting that the voting public isn’t giving Biden enough credit. Look at just about any macroeconomic indicator and you’ll find a success story: GDP growth in the second quarter of this year exceeded expectations, inflation has dropped for the last 11 months, unemployment is at 50-year lows. Since the end of 2021 and the passage of Biden’s trademark legislative achievements, manufacturing construction spending has doubled.

Despite all that, just 37 percent of voters approve of President Biden’s handling of infrastructure issues. Only 41 percent approve of how he’s handled jobs and unemployment, while a dismal 26 percent approve of how he’s dealt with inflation.

That all spells trouble in the years to come. Recent polls show a tighter-than-expected race between Biden and Trump in a 2024 face-off. If Biden fails to carry a national ticket and deliver a congressional majority, the GOP will do everything it can to undo the modest progress his administration has made on climate. Powerful conservative think tanks with deep ties to fossil fuels have already drawn up a “battle plan” for the next potential Republican president, which would entail revisiting evergreen right-wing priorities like dismantling climate and environmental protections while ordering even more drilling and mining of dirty energy.

Decarbonization is a decades-long project requiring a dramatic, wholesale transformation of the energy system—changes stretching far beyond even the best expectations of the IRA. Most all of the emissions reductions the law is expected to produce—roughly 10 percent more than what would happen in a world without the IRA—will come from the grid. Emissions from major polluting sectors like transportation and buildings will be relatively unaffected, according to modeling of the IRA’s climate impact. Decarbonization will also necessitate a head-on battle against powerful and politically influential fossil fuel producers, whose core business model (digging up and selling carbon) will need to be wound down in order to keep even modest climate goals within reach. There is much more work to be done to zero out carbon emissions, and a very good chance that the GOP—effectively a political arm of the fossil fuel industry—could stop that work in its tracks.

Democrats will need to hold on to at least some amount of governing power to keep that from happening. But pointing at climate models hasn’t convinced governments to take action, and pointing at charts showing how good the economy is won’t convince voters to elect the people responsible for making things better. The question remains: How can the party best capitalize on their work to date, using it to whet appetites for the even bigger changes that are needed?

“Bidenomics,” as the White House has branded its policy vision, rests on a basic theory: that the government should steer private sector investment into twenty-first-century growth industries to boost the middle class. Those voters, in turn, will be endeared to Democrats as a result. A revived manufacturing sector, in particular, will create dignified and well-paid work for millions while allowing the United States to better compete with its geopolitical rivals. “When you invest in our people, when you strengthen the middle class, we see stronger economic growth that benefits everybody,” Biden has said.

As statistic after statistic shows, the growth and investments Bidenomics promised have started to happen; Bidenomics is succeeding on its own terms. Yet people don’t seem to experience the idea of the economy through the numbers by which the administration is judging that success.

That’s not to undersell the genuinely impressive things that the Biden administration has pulled off, not least of which is lowering inflation without spiking unemployment. And while the IRA is not a fully fleshed out program for decarbonization, its investments in clean energy will be invaluable for cleaning up the power sector and convincing other countries to pursue their own green industrial policies.

Plenty of thinkers have pointed out the limits of Bidenomics. The New York Times’ Ezra Klein and Matt Yglesias see a core barrier to Biden’s agenda as run-of-the-mill government dysfunction: administrative capacities that have become overburdened by decades of haphazardly accumulated rules and regulations. “Do we have a government capable of building? The answer, too often, is no,” Klein wrote last spring. “What we have is a government that is extremely good at making building difficult.” He argues that loading up new policies with too many noble but extraneous social goals—prevailing wage provisions and local hiring provisions—could further slow those much-needed building projects.

I’m sympathetic to Klein’s argument: The U.S. does indeed need to build lots of stuff in order to deal with the climate crisis. But peeling back bureaucratic red tape is a less important barrier to decarbonization than maintaining and strengthening the extraordinary fragile political coalition that allowed us to finally get started on this massive project.

Debates over how to build, though, have paid comparatively little attention to what’s being built, and how that might color voters’ interest in that project. In the wonky circles where these conversations play out, few would argue about the need to rapidly deploy massive amounts of clean energy or bolster domestic supply chains. Subsidies for those things create jobs: Since the IRA passed, more than 100,000 new clean energy jobs have been created. Companies are relocating to the U.S., enticed by subsidies. It’s now cheaper to buy an electric vehicle and install solar panels on your house than it was before the IRA passed.

These laudable changes are—on their own—pretty boring. Few people get up in the morning excited about the U.S. share of manufacturing employment, or tax credits to install heat pumps. That necessary, boring stuff may well be the most important part of decarbonization. As depressing polling these last few weeks may indicate, however, ramping up productive capacity and making green things cheaper might be insufficient for endearing voters either to Democrats or the transformational project of decarbonization. Inherent to that project, too, is being able to overcome the massive political resistance of a fossil fuel industry that attacks even modest climate policy in Congress, and which has powerful spokespeople in state governments and agencies that play a pivotal role in deciding whether and where clean energy infrastructure gets built.

Left out of most conversations about industrial policy is the question of whether people are having a nice time. Low rates of unemployment are an essential foundation for that. As the old adage goes, the only thing worse than having a job is not having a job—particularly in a country where basic needs like health care are controlled by for-profit companies. Still, work also mostly sucks, even in the sadly rare event that your job is relatively well-paid and unionized. And people don’t much care how their lights turn on so long as they do.

It’s perfectly understandable why policymakers would fixate on the big stuff like factories, energy, and macroeconomic indicators: They’re important! When liberalism has built at scale, though, its massive public works projects and focus on job creation were part of a much broader vision for the sort of life a government ought to provide the people it governed.

The New Deal created 20 million work relief jobs from 1933 through 1942, clawing unemployment levels down to pre-Depression levels. It built a tremendous amount of infrastructure along the way, constructing 381,000 miles of power lines that electrified rural America, more than 400 post offices and nearly 900 sewage disposal plants (to name just a few).

It also built a hell of a lot of places for people to have fun. The Civil Works Administration constructed 2,000 playgrounds and 4,000 athletic fields; the National Youth Administration built, repaired, or improved more than 9,000 tennis courts; the Civilian Conservation Corps mounted 2,500 cabins in state and national parks and forests. Posters designed by artists employed by the Federal Arts Project advertised all the good the New Deal was doing, while out-of-work actors and writers put on plays and penned travel guides. Gargantuan projects like the 24-story high Norris Dam, which was built with an attached visitors’ center, were designed to be marveled at. Power lines erected by the Rural Electrification Administration came with signs that told anyone walking or driving by exactly who was responsible.

Investments in those things weren’t a sideshow to a White House squarely focused on lowering unemployment and modernizing the country’s infrastructure, but an essential part of that project. “We must plan for, and help to bring about, an expanded economy which will result in more security, in more employment, in more recreation,” Roosevelt said at a 1943 press conference, by then 10 years into a commanding Democratic majority in the House and Senate that would hold, almost continuously, for decades. To credit tennis courts and cabins for those margins wouldn’t be exactly right. New Deal liberalism, however, was self-consciously interested in making the case for itself to the public by making tangible improvements in the lives of working people.

The public improvements made during the New Deal could also be crucial to helping the U.S. navigate a climate-changed world. Take swimming pools. Pools are vital infrastructure to have in place as temperatures rise, giving people a free place to cool off during extreme heat waves like the one that blanketed the country in July. The New Deal built around 750 public pools between 1933 and 1938, and remodeled thousands more. They’re an example of the sorts of public institutions that help provide cooler physical spaces as well as foster social bonds that are essential to surviving the climate crisis. Public libraries, similarly expanded by the Works Progress Administration, likewise act as a community resource, offering air conditioning, shelter, and internet access.

Like many public institutions at the time, New Deal leisure infrastructure was often segregated—a poison pill that not only limited public accessibility, but helped usher in mass closures. As The Sum of Us author Heather McGhee and others have detailed, white officials began to close or privatize public pools as activists sought to integrate them during the Civil Rights Movement; rather than open pools to anyone who might want to use them, reactionary governments closed them off to everyone. Swimming became a more rarified commodity: Richer communities erected private pool clubs, and wealthy families built pools in their own backyards. The CDC estimates that there are now roughly 10 million private swimming pools in the U.S.—but just 309,000 public ones.

The closing of pools and other communal spaces in the U.S. was part of a broader neoliberal project to undermine the ability of the government to do big, good things for working people. Right-wing, segregationist thinkers and business elites, including James Buchanan and a young Charles Koch, became key architects of the radical right’s crusade against the New Deal order through the latter half of the twentieth century. By the 1990s, the idea of a liberalism that built stuff had become an anachronism. Democrats—trying to win back their long-held congressional majorities—largely acceded to the idea that the market, not government, was best-suited to deliver any of the big, good things that society might need.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the destruction of public institutions the right fought for coincided with an alarming spike in loneliness. Twelve percent of Americans report not having any close friendships, up from just 3 percent in 1990. That’s both a sad reflection on mental health in the U.S. and a climate vulnerability. Researching the 1995 Chicago Heat Wave, sociologist Eric Klinenberg found that people who succumbed to extreme temperatures were often those who were most isolated.

“Places with active commercial corridors, a variety of public spaces, local institutions, decent sidewalks, and community organizations fared well in the disaster,” Klinenberg wrote in 2017. “More socially barren places did not. Turns out neighborhood conditions that isolate people from each other on a good day can, on a really bad day, become lethal.”

These kinds of places are a tough sell to investors, though. What sort of returns can Wall Street expect from a library that gives away books for free, and serves as a cooling center during a heat wave? Where is the revenue stream from letting people host their kids’ birthday party at a public pool?

Bidenomics represents an important sea change among elite policymakers, who now recognize that government spending can steer private cash into strategic sectors. The IRA offers hundreds of billions of dollars (at least) for companies to invest in clean energy and electric vehicles. Unlike wind turbines or cars, though, libraries and public pools aren’t commodities to be sold at a profit: They exist to serve the public or they don’t exist at all.

According to McKinsey, $216 billion of the $394 billion in energy and climate-related tax credits dispersed by the IRA—more than half—will accrue to corporations. Many more will go to consumers able to afford the still considerable up-front costs of decarbonizing their homes and cars. As the White House worries over how to sell the IRA and other achievements, its focus on economic competitiveness and job creation shouldn’t crowd out either what people do off the clock or the project of building a political coalition for decarbonization. Not all of the elements that transformation requires will be return-generating assets. With relatively few people still either aware of or happy about Bidenomics-style industrial policy, seemingly unproductive investments in public institutions could be a way to win voters over.

The IRA’s goals of building green infrastructure and industry are only part of what’s required to confront the climate crisis. It’s great news that it appears to be succeeding on its own terms. That so few people know what it is should be a wake-up call that green industrial policy alone isn’t a gateway drug to deep decarbonization, or, relatedly, reelection. As the GOP scaremongers about the perils of net zero, Democrats have to credibly explain why the decarbonized country they’re calling for will be better than the one we know now.

Why not give people something to enjoy about decarbonization instead of just a daunting to-do list of large-scale infrastructure projects? Call it Pool Party Progressivism: a politics recognizing that the unionized workers erecting all those wind turbines and solar panels might want to go sit by the water with their friends and family after work, grow zucchini next to their neighbors, or join a rec soccer league. That will mean finding ways to invest in things that companies won’t. The government, though, gets to take all the credit—not just for some impressive set of economic indicators but for strengthening communities and letting people have some fun cutting carbon.