On June 2, 1863, not long after midnight, 300 recently escaped slaves, all armed and with at least one woman among them, invaded a stretch of rice plantations along the Combahee River in South Carolina. When the armed Black rebels arrived, the slaveholders fled, but their enslaved workers refused to follow them. Instead, at least 727 of them followed the rebels to nearby boats, which ushered them to a military camp, declared them free, and armed those able to fight. Meanwhile, as dawn approached, the retreating Black rebels set fire to the abandoned slave labor camps, depriving the slaveholders’ army of a vital source of food, and delivering a major victory in the Black rebels’ larger war on slavery.

Given the scale of the invasion and the number of Black people emancipated, this attack, known as the Combahee River Raid, could plausibly be considered the largest slave rebellion in American history. It might even be called the largest slave rebellion in what was the largest slave revolution in modern world history. Not even the Haitian Revolution—the first successful slave-led war to overthrow slavery—liberated as many Black people as the one in which the Combahee River Raid was only a part.

Accounts of the Combahee invasion have, somehow, been incapable of imagining it as a slave rebellion, much less part of a larger slave revolution. Yet the American slave revolution, which we have come to call “the Civil War,” shares all the hallmarks of the Haitian Revolution, on an even grander scale. Just as in Haiti, America’s slave revolution came amid a larger white man’s war, which slaves transformed to include their own revolutionary agenda: immediate emancipation and full Black citizenship. Just as in Haiti, America’s enslaved Black revolutionaries allied with white military forces to achieve their goal of emancipation. America’s Black radicals even convinced liberal white reformers, the core of the Republican Party, to become momentary revolutionaries themselves: As the Jacobins did in France, the Republicans in America formalized the freedom that slaves won for themselves, in places like Combahee, by enshrining emancipation in the United States Constitution.

In some ways, America’s slave revolution was even more radical than Haiti’s. America’s Black revolutionaries did not force most of the white people to leave, nor did they create an exclusively “Black” republic. Instead, they persuaded their leaders, in large part on account of their wartime activities, to enshrine the more revolutionary principle of universal citizenship, regardless of class or race. Nor, as Haitians and most other emancipated peoples were forced to do, did America’s Black rebels compensate their former enslavers for their lost “human property.” To be sure, Black radicals hardly got everything they demanded. There would be no land given to them, to say nothing of reparations. Nor would they receive protection against the vicious white backlash that followed in their revolution’s wake. But perhaps most troubling is that, even today, few people see the war waged by enslaved Black Americans as a veritable revolution. How did we miss it?

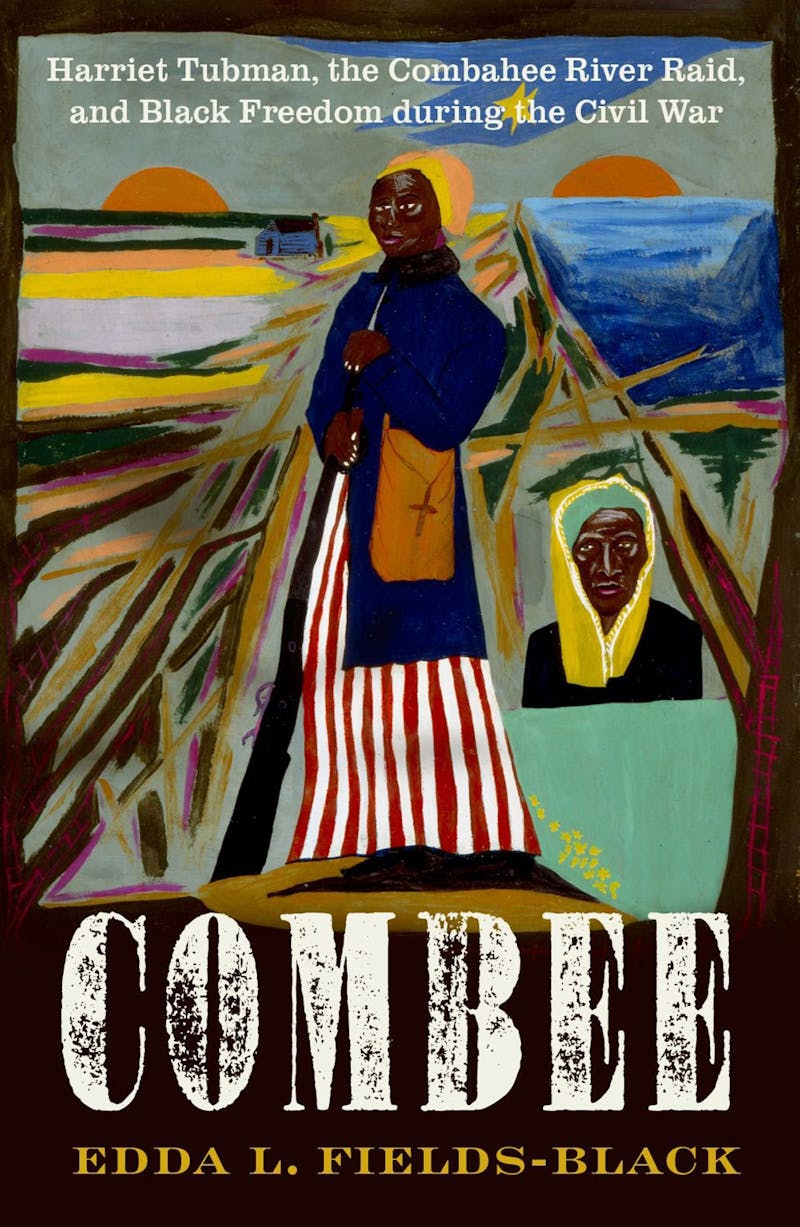

It is the task of Edda L. Fields-Black’s remarkable new history, Combee, to recover part of this ignored slave revolution. Her focus is not on the entire war, only its most significant battle: the Combahee River Raid. Though hardly unknown to historians (and perhaps best remembered for the Black feminist collective that took its name as inspiration), the raid is one of the least studied battles in what we call the Civil War, and it features as only a bit chapter in the revolutionary life of one of its main participants, Harriet Tubman. Fields-Black, an accomplished historian of West Africa and the slave South, as well as a descendant of one of the Combahee slave rebels, has set out to restore this battle to its proper place in the life of Harriet Tubman and the larger war on slavery, calling it “the largest and most successful slave rebellion in US history.”

To tell this story, Fields-Black relies on an underutilized archive. The pension files of former Union soldiers, housed at the National Archives, contain, Fields-Black tell us, thousands of pages of testimony from the dependents of Black Civil War veterans, of which there were 186,000, 75 percent of whom were formerly enslaved. Because dependents had to collect a massive amount of evidence from formerly enslaved friends, neighbors, and surviving veterans to receive a pension, these files offer a trove of largely untapped information about enslaved people in their own words. At a time when many scholars of slavery argue that traditional sources only perpetuate the violence of slavery, Fields-Black reminds historians how much is left to discover: she “did not want to write another book about what we don’t and can’t know about enslaved people, because of the gaps, silences, and violence of the archival record.” Instead, she rolled up her sleeves, dove into the archive, and has now produced what is undoubtedly the most authoritative account of this unheralded slave revolt.

Fields-Black begins this story with what occurred on the Combahee rice plantations in the years leading up to the raid. Many of the slaves who would flee to the invading Black army had recently watched their enslavers sell away their family members. As Fields-Black notes, the recent or imminent sale of family members was often the catalyst that drove slaves to escape throughout the antebellum period. In this, the Combahee River “freedom seekers,” as Fields-Black calls escaping slaves, shared much with Tubman. On September 17, 1849, shortly after her enslaver sold her niece, Tubman and her two brothers decided to escape their Maryland plantation. Her brothers got cold feet, leaving Tubman to escape on her own. But it was an agonizing choice: By fleeing on her own, she left behind her husband, parents, siblings, and the familiar Black community in which she was raised.

Fields-Black argues that what made Tubman so exceptional—and what made the Black rebels that invaded the Combahee River plantations so exceptional—was their decision to return to the site of slavery to liberate other enslaved people. Very few Black people who escaped slavery before the war—not Frederick Douglass, not Sojourner Truth, hardly any of the famed Black abolitionists who were once enslaved—risked returning to the slave South to emancipate other Black people. Tubman, most famously, had taken this risk nine times before the Combahee River Raid, as a prominent agent of the Underground Railroad. Indeed, she is best remembered not for her military service but for liberating 70 enslaved people, many of them family members, before the war. Yet her work on the Underground Railroad was only the start of her “revolutionary activities,” Fields-Black writes.

What was equally remarkable was that Tubman did not know any of the enslaved people she helped emancipate on the Combahee River Raid. One of Combee’s many strengths is to show the vastness and diversity of the antebellum South’s enslaved Black communities. Tubman, Fields-Black reminds us, was born in Maryland on American soil, as were her parents, both of whom were “relatively privileged,” if no less brutalized. Her mother was a house slave and cook, her father an enslaved inspector and foreman. Indeed, though Tubman insisted on working in the fields alongside common enslaved laborers, she was initially raised to be a house slave, just like her mother.

By contrast, most of the armed Black rebels and freedom seekers from South Carolina’s Lowcountry were forced to do more field labor and had a more African-influenced culture. Rice, the main crop along the Combahee River, was extremely labor-intensive and required a large enslaved workforce. Due to the number of laborers required, enslaved rice laborers tended to live in dense camps far from white settlements, unlike slaves in Maryland, many of whom lived on small plantations and had greater interaction with whites. Because rice was cultivated in malaria-infested swamps, rice plantations also had a high death rate. This in turn meant that rice enslavers were constantly purchasing new slaves from Africa to replenish their workforce, up to and even after the United States banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1807. On the eve of the war, many Lowcountry Black people had either a parent from Africa, or lived among aging African-born slaves. Lowcountry slaves thus had a distinct language, practiced a strongly African-influenced religion, and, as with many West African cultures, named their children after the day they were born. Tubman later remembered that when she first met the armed Black rebels and freedom seekers of South Carolina, “Dey laughed when dey heard me talk. An’ I could not understand dem, no how.”

In highlighting the differences between Tubman and Black people in the Lowcountry, Fields-Black implicitly asks readers to question any assumption they might have about Black people “naturally” coming to each other’s rescue. Before the war, nearly all the Black people Tubman liberated were either family members or people she knew from her tight-knit Maryland community. So what changed? Why did Tubman go beyond the rescue of familiars and into the rescue of strangers?

Not content to assume an innate racial solidarity, Fields-Black argues that Tubman’s friendship with John Brown may have inspired her, at least in part. Tubman met Brown, the militant white abolitionist, in April 1858, when Brown came to Ontario to recruit Black freedom seekers to join his interracial abolitionist militia. Tubman recruited several Black men to his militia, although, lacking funds, they were unable to travel to his training camp. Nonetheless, after Brown was executed for his failed attack on Harper’s Ferry one year later, Tubman developed a newfound willingness to die for Black people she did not know—just like John Brown. “When I think about how he gave up his life for our people, and how he never flinched,” Tubman said after Brown was executed, “its clear to me it wasn’t mortal man, it was God in him.”

Before Tubman arrived in South Carolina, the Union army had already occupied Port Royal, on South Carolina’s southeastern coast. Though Lincoln had not yet announced the Emancipation Proclamation, thousands of Black freedom seekers had been escaping to Union camps around the country for over a year. In doing so, they forced immediate emancipation, and armed Black warfare, onto Lincoln’s agenda, something he judiciously avoided in the war’s early years. But in Port Royal, the Union’s white occupying leaders made an egregious error. Rather than treat Lowcountry freedom seekers as equals, they pressured them to work as low-paid wage laborers on abandoned cotton plantations run by white Northerners. They hoped to “prove” to the outside world that Black people were not lazy and would gladly work for white landowners, if only paid a wage.

Of course, most Black people resented being forced to work for what they derisively called “Yankee Buckra”—Northern whites—who they felt were treating them no different from Southern “Buckra.” Worse, several of the Northern white men hired to run the confiscated cotton plantations began to whip Black workers who resisted their exploitation. Meanwhile, the Union army began to conscript, against their will, freedom seekers who escaped to Union lines. Increasingly, Black freedom seekers felt they were being forced to fight in a white man’s war, rather than for their own liberation.

Enter Harriet Tubman. In early 1862, Massachusetts’s abolitionist governor recruited Tubman to help recruit Lowcountry freedom seekers to the Union army. Because Black people in the Lowcountry increasingly distrusted the Union forces, the governor felt Tubman, already famous for her Underground Railroad exploits, could help.

Though it took Tubman time to win their trust, she had a talent for forming bonds of solidarity with regular Black folk. Fields-Black illustrates this beautifully with the contrast she paints between Tubman and Charlotte Forten, a free-born Black abolitionist from Philadelphia. Forten experienced no shortage of racism, but she was light-skinned, highly educated, and born to one of the wealthiest Black families in America. What she lacked was Tubman’s common touch. Unlike Tubman, who elected to live in modest housing in South Carolina, Forten chose to live in an abandoned enslaver’s mansion. Forten found Black Southerners’ “ring shout”—an African-influenced dance practiced during worship—“barbaric,” as she wrote in The Atlantic, “destined to pass away under the influence of Christian teachings.” By contrast, Tubman jumped in and joined them.

In addition to Tubman’s ability to win Black southerners’ trust, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, galvanized the Black recruitment effort. The proclamation made official what had only been decreed locally, ambiguously, and often inconsistently by individual Union officers in the field. Because Lincoln’s proclamation, in practice, only emancipated people in Confederate territory controlled by the Union army—which was not much—its greater significance was that it allowed Black men to enlist in the U.S. military. Rather suddenly, the white man’s war converged with enslaved Black revolutionaries’ interests: the armed overthrow of slavery.

Over the next six months, Tubman recruited a ring of Black freedom seekers in the region to collect intelligence for what would become the Combahee River Raid. The invasion’s goal was simple: Deprive the nearby Confederate army of food by destroying the region’s rice plantations, and free and arm as many enslaved people as possible. Beyond collecting intelligence for the raid, Tubman was also responsible for recruiting Black freedom seekers into a newly formed Black unit that would lead the invasion: the Second South Carolina Volunteers. One of those enlistees was Fields-Black’s ancestor, Hector Fields. Together with Tubman, the unit’s white abolitionist commander, James Montgomery, and a separate all-white unit from Rhode Island, Hector Fields and the armed Black rebels of the Second South Carolina Volunteers would foment one of the most brazen slave uprisings in U.S. history.

The first company of the Black rebel unit invaded the Tar Bluff slave labor camp in the darkest hours of the June 2 morning. Union gunboats dropped off several more Black companies on nearby rice plantations in the following hours. When plantation owners woke to the sound of armed Black rebels invading their property, at least one understood what was happening: a “repetition of San Domingo”—Haiti—he later recalled. The rebels torched mansions, barns, warehouses, and flooded rice fields. Though most slaveholders escaped, they failed to convince their enslaved workers to follow them. Instead, they followed Tubman and the other Black soldiers to the Union boats that carried them to freedom. Hagar Mack, no older than five when the Black rebels liberated her slave labor camp, remembered the day vividly. “A barn, ten thousand bushels [of] rough rice, all in a blaze.” She went on: “Didn’t care notin’ at all, I was gwine to the boat.”

The Combahee River Raid, however, is not an entirely triumphant story. Not all freedom seekers who escaped made it in time, and others were turned back when the Union boats became overcrowded. In the final chapters of Combee, Fields-Black details the many other travails faced by the Black unit, and those liberated by them, after the invasion. The Black rebels only shot one white enslaver, after he fired on them, but the scorched-earth policy—conceived and approved by the unit’s white commander—played into the racist imaginations of many white people, in the North and South. Many whites believed that arming slaves would only lead to a vicious anti-white race war, and all they needed were a few burnt rice plantations to prove it. Worse, after the war, only 42 percent of Black veterans’ dependents who applied for a pension received one. Even Tubman had to apply three times, and wait 30 years, before Congress approved hers—which, Fields-Black writes, amounted to “crumbs.”

But in its most fundamental sense, the Combahee River Raid was an astonishing victory. Nearly 300 recently emancipated Black rebels had liberated, in six hours, more than 700 enslaved people. Roughly 150 of those emancipated at Combahee would themselves join the ranks of the quickly growing all-Black revolutionary brigades. In the next two years, tens of thousands of Black American revolutionaries would go on to liberate even more slave labor camps throughout the South. Allying with a Northern white military, they ultimately destroyed the largest slaveholding empire in the nineteenth-century world—the United States—emancipating four million enslaved Black Americans. Their revolution also precipitated the downfall of the Western hemisphere’s last two remaining slave societies, Cuba and Brazil. It was no small accomplishment.

If there is a flaw in Combee, it is that Fields-Black does not spell out this larger significance. She makes the right provocation, defining the Combahee River Raid as “the largest slave rebellion in US history.” But without a deeper justification for that claim, other than the number of Black people liberated, readers may not grasp the importance of what she is saying. Fields-Black is not the first to conceive of Black-led invasions like the one at Combahee as “slave rebellions.” Perhaps the first to do so was W.E.B. DuBois, who, in the 1930s, called the Civil War’s collective slave escapes, work stoppages, and Black military service the “largest and most successful slave revolt” in American history. More recently, the historian Steven Hahn made the strongest case, calling all the actions of enslaved Black Southerners during the Civil War one massive “slave rebellion.”

Fields-Black implicitly picks up on this lead, but she suggests that the reason the Combahee River Raid is not remembered properly is because so many of its participants, including Harriet Tubman, were illiterate. They did not, in other words, leave enough of a paper trail. While undoubtedly a factor, illiteracy is only a part of it. As Hahn argued, the more fundamental reason most historians do not consider the Combahee River Raid, and many more Black Civil War actions like it, a “slave rebellion” is because they fail to see enslaved Black people as legitimate political actors. At most, their actions can “influence” or “shape” the broader contours of the Civil War, but they do not fundamentally alter how they see it.

But there is more to it than that. Many imagine that a slave rebellion must entail something like a bloody race war. That is the dominant image of slave rebellions even to this day, whether we are talking about Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, or Toussaint Louverture. Yet the fact is that few enslaved Black rebellions, in America or elsewhere, entailed gratuitous massacres of undifferentiated racial groups (for the most part, only white people did that). That the slave rebellions—I prefer the slave revolution—that occurred amid the Civil War, that was the Civil War, entailed even fewer instances of wanton white murder, in a strange way, disappoints: Black revolutionaries are imagined as blood-lusting primitives, not the strikingly restrained men—and even women—in uniform they were.

Perhaps as troubling, many cannot conceive of an armed Black rebellion including so many white people. Indeed, often overlooked is the fact that even Haiti’s Black generals had allied, at various points during their revolution, with the largely white militaries of Spain, Britain, and republican France to gain their freedom. Had Napoleon not overthrown the radical Jacobin government in France, voided their emancipation decree, and tried to re-enslave Black Haitians, a post-emancipation Haiti might well have remained a free Black colony within a white French empire, rather than, by 1804, an independent Black republic.

In other words, both the racist imaginings of the “savage African,” and the racial-essentialist imaginings of Black “self-liberation,” prevent us from seeing the radical nature of these slave-led revolutions. Whether it was the Black revolution in Haiti, or the Black revolution in Civil War America, enslaved Black people fought alongside whites not because these white people were antiracist—not many were—but because the two factions came to share overlapping interests. Especially in the United States, where Black people were always a decisive minority, Black revolutionaries had no other option: They went to war with the army they had, as it were, not the one they wanted.

The tragedy is that few have been able to see not only the immense achievement of these enslaved Black American revolutionaries: Few even can imagine they existed. Perhaps Combee will start to bring their stories into view.