“A novel about Treblinka,” Elie Wiesel famously remarked, “is either not a novel or not about Treblinka.” The Zone of Interest, a new film by the English director Jonathan Glazer, is set in Auschwitz, though one might say isn’t “about” Auschwitz. How can it be if we can’t see the images by which we all know Auschwitz? In The Zone of Interest, you won’t have to look at any killings. You won’t see anybody get shot, gassed, or beaten. There are no selections on rail platforms, bunker cells, marches into gas chambers, no signs reading “Arbeit macht frei.” Trains appear ever so briefly and in the distance; you don’t see inside a crematorium until the penultimate scene, and even then it is not exactly what you might expect.

The picture opens in complete darkness that, after a few minutes, suddenly cuts to the shores of a gorgeous lake, where a picnic is underway. Father watches as his boys play in the glassy water; mother takes a lazy stroll with her baby in her arms, following just behind her two girls and the nanny. In other words, this is a perfect day in the life of an orderly family, and when dusk arrives they drive home to what could be any one of any number of simple suburban houses anywhere. Except when dad heads to work the next day, he goes next door—to a concentration camp.

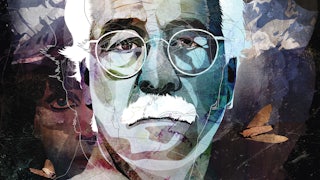

This is the family of Rudolf Höss, one of the architects of the Holocaust, played by Christian Friedel. The historical Höss used the slave labor of Jewish and other prisoners to transform a former army barracks in the Polish town of Oświęcim into a parent camp and administration center; he identified a site about two miles away that was to become the much larger Birkenau, where most of the exterminations occurred; and essentially created the “zone of interest,” or Interessengebiet, a 40-square-mile area that includes towns, stations, prison factories, and 40 camps and subcamps that make up what we call Auschwitz.

Although the zone was large, Höss lived on the same street as the crematorium, only a few hundred yards away. He was commandant from 1940 to 1943, and again in 1944, and in 1941, it was Höss who implemented his deputy’s discovery that the pesticide gas Zyklon B could be used to kill many human beings without bloodshed. He was in command when the Final Solution began in 1942, and some 10,000 Jews were murdered every month in Birkenau. He would maintain to the bitter end that his wife and children knew nothing of the crimes committed just over the wall. Höss himself is blindfolded in one of the first shots we see of him—his kids are surprising him with a canoe; it’s his birthday. It becomes clear over the course of the film that not only does everyone know what goes on in the camps; most are happy to prosper from it.

We watch, for instance, as a Polish prisoner wheels a barrow full of silk undershirts and canned goods to the villa. Höss’s wife, Hedwig, played with unnerving disinterest by Sandra Hüller, opens one of the packages to reveal a fur coat; she tries it on in front of a mirror, clothed in satisfaction. She finds a tube of lipstick in the pocket; then you notice gunshots in the distance. The Höss family goes about daily life as human screams and incinerator roars grow louder—the camera might be looking away, but you hear everything.

The averted gaze is crucial for Glazer in making art about the Holocaust, treating a subject whose horrors have often appeared too great to capture directly. There are hints in his film of the knowingness of the camera in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, another movie about a sentient “zone” that brings to mind the camps of the Nazis and the Soviets, or hints of W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, a novel not about but constantly visited by Auschwitz, which begins and ends with the same syllables. Glazer holds us captive in The Zone of Interest with a “civilized” camera that deliberately looks away (or lies, ignores, conceals, expunges, forgets, denies), a “barbaric” script, and a soundtrack that stubbornly intrudes and upsets the quietude.

The Zone of Interest is billed as a loose adaptation of Martin Amis’s 2014 novel, which portrays a Nazi love triangle in Auschwitz, where the commandant is the fictional Paul Doll, though the film takes little more from Amis than its title. Glazer embarked on years of research in and around the zone, including gathering dialogue actually spoken by Rudolph and Hedwig. “I could have my husband spread your ashes across the fields of Babice,” Frau Höss really did tell a long-suffering maid who dared to leave a dish out on the breakfast table a little too long. “Don’t forget you live well in our house!”

Glazer also found many of the Höss family’s personal photographs, and set about recreating them: Rudolf takes his kids on the birthday canoe down the Sola River; Hedwig throws a pool party, and all that’s keeping it from resembling a present-day American suburban backyard is the lack of a bouncy castle for the kids. The sense of immediacy is helped by the way the film is shot—on 10 stationary digital cameras, many of them hung on walls to record like a fly, as if we’re watching surveillance footage. I counted only two tracking shots in the entire film. The goal is to scrub free any hint of manipulation.

The Hösses present a contented appearance to their friends and family. All is well, Hedwig assures Linna, her visiting mother, and laughs that her husband calls her the Queen of Auschwitz. Linna even wonders aloud whether a woman she used to clean for “is over there,” and complains she got outbid on her curtains. Daughter proudly shows off the villa’s garden only for Glazer to show us later what has enriched and made possible this resplendent Eden, fertilized by human remains.

In a film filled with cruelty, the most repulsive moment comes when Hedwig and her neighbors are sipping coffee in her kitchen, and Frau Höss is mocking a friend who asked her where she got her jacket. “I told her Canada. She said, How could you go to Canada? She thought it was the country!” The remark is devastating, but some will pass over it unscathed, while others will be gutted knowing that “Canada” was the euphemism for the death camp’s storage facilities, named so by Polish prisoners who believed the country was the world’s wealthiest.

Beneath the sheen, cracks are forming. We see Höss’s 6-year-old son, Hans, playing with toys in his room, as we hear his father outside ordering a prisoner who fought over an apple to be drowned in the river. “Don’t do it again!” Hans mutters. Ten-year-old Inge-Brigit, who wanders at night, tells her father that she likes passing out pieces of sugar. “To who?” Höss asks. “I’m looking,” as Inge-Brigit stares out the window at the incinerator chimney glowing red. Linna is awakened by the same sight, and covers her nose with a handkerchief. She leaves in the night without so much as a goodbye to her daughter. And what a pity when Höss must cut short a day of fishing with his children because human remains are flowing right past them, after which the kids receive a furious scrubbing.

It takes some doing to pick up all of the fugitive details, but The Zone of Interest is built on the importance of noticing. I won’t soon forget the face of the housemaid as she is tasked with washing the bathtub stained with the ashes of what could have been her family and friends. I’ve heard complaints that nothing happens in The Zone of Interest. In fact, so many traumas are brought up that it’s difficult to keep pace; I’ve watched it three times, yet I’m still dodging fresh blows.

The Zone of Interest is an open indictment of the act of not looking. Just as the firing of weapons and painfully unbearable screams grow loudest, Glazer and his tremendous cinematographer, Łukasz Żal, blanket the entire screen in smoke that fades to white. I’ve seen viewers look like they’ve suddenly become very aware of themselves at this moment, and uncomfortably so.

Or witness the abrupt cutting to a girl who at night places apples where prisoners work during the day, and finds a tin and takes it home. The tin contains the sheet music for “Sunbeams,” a song composed by the historian Joseph Wulf, who survived Monowitz, the labor camp of Auschwitz. There really was such a girl, whom Glazer met when she was 90 and still living in town. Many of the shots were made using a thermal camera, which has the effect of disorienting the viewer, as if we’re suddenly looking through the consciousness of the “zone.”

Such was Höss’s moral stupor and mental denial that he claimed to not have mistreated a single prisoner, let alone killed one. He simply went about carrying out orders, “a cog in the wheel of the great extermination machine created by the Third Reich,” he said. In the film, we see him welcoming two gentlemen from the venerable firm of Topf and Sons, as they proudly present the designs of a rotating incinerator that burns 500 bodies “continuously.” Later, he chairs what could be a regular corporate meeting: Delegates open their file folders, flip to a page, and start talking about “timings.” The men of the SS bang on the table to applaud a fellow director who has consistently hit his quota. He’s told that he’s returning to Auschwitz, to direct one of the largest extermination campaigns the world has ever seen, which nearly wiped out the Hungarian Jews, massacring more than 300,000 in less than two months. When Himmler names the operation after him—Aktion Höss—Höss is so elated that he cannot wait to call Hedwig to tell her the news.

We spot Höss one final time as he leaves the Oranienburg compound, but not before he looks down a dark, empty corridor, toward the camera. We see what he sees: complete darkness, except for a slim tunnel of light that recalls the projector of a movie cinema. It is in fact the door of the gas chamber of the crematorium, and we are inside the present-day Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, where one woman sweeps the floor while another wipes down the iron furnaces. More cleaners file past displays of mountains of suitcases, spectacles, shoes—Höss’s diligence is compared to another kind of cleansing, one of duty to the ruins of pain.

The screen cuts to black, but you’d be mistaken to think the ordeal is through. The Zone of Interest ends the way it began, with complete darkness overwhelmed by some three minutes of extraordinary music by the English composer and singer Mica Levi, who summons a chorus of pain out of whispers, groans, and chants over an unrelenting and otherworldly haze of ascending and descending arpeggios. The Zone of Interest tenders the most powerful sonic encounter of recent memory, from “Sunbeams” to the sight of a mutilated soldier enjoying a Strauss march, to what I detect is a hint of the polka “Rosamunde” being broadcast as a form of mocking torture inside the walls of the camp; music was heard, after all, even in Auschwitz. But it is Levi’s refrain that represents the soul of the tortured “zone,” and will continue to get under my skin.