1987 was arguably the year Donald Trump became Donald Trump. While he’d been one the most famous and outspoken men in New York for nearly a decade by then, the publication of The Art of the Deal—his ghostwritten guide to success—made him a household name and a fixture on television. That December, he appeared on CNN’s Crossfire to celebrate himself and field questions from hosts Pat Buchanan and Tom Braden befitting his standing as an icon of American business. What do you intend to do next as a billionaire? Will you give to charities and causes? Might you run for president?

Late in the show, Buchanan asks Trump what might have been the interview’s most difficult question: “Who are your favorite authors?” “Tom Wolfe is excellent,” he replies. Had he read The Bonfire of the Vanities?

“I did not.”

“What book are you reading now?” Braden chimes in.

“I’m reading my own book again because I think it’s so fantastic, Tom.”

“What’s the best book you’ve read beside Art of the Deal?” Buchanan asks.

“I really like Tom Wolfe’s last book. And I think he’s a great author. He’s done a beautiful job —”

“Which book?”

“His current book.”

“Bonfire of the Vanities.”

“Yes. And the man has done a very, very good job.”

While it’s comically difficult to tell from this exchange whether Trump really read The Bonfire of the Vanities, it’s also entirely plausible that he did—alongside The Art of the Deal, it was one of the year’s bestselling and most talked about books. And part of the appeal to Trump might have been that it is substantially about the world he inhabited—a satire filleting go-getting Manhattanites with money to burn and a deep fear of the city’s minority underclass.

But it’s just as plausible that Trump never actually touched it. Bonfire was, after all, a book many purchased as a signifier or accessory—talked about enough in the press that one could easily pretend to have at least picked it over, a conversation piece for a living room table or the crook of one’s arm on the subway. It was, in short, the kind of status marker the book was written, at least in part, to mock and critique.

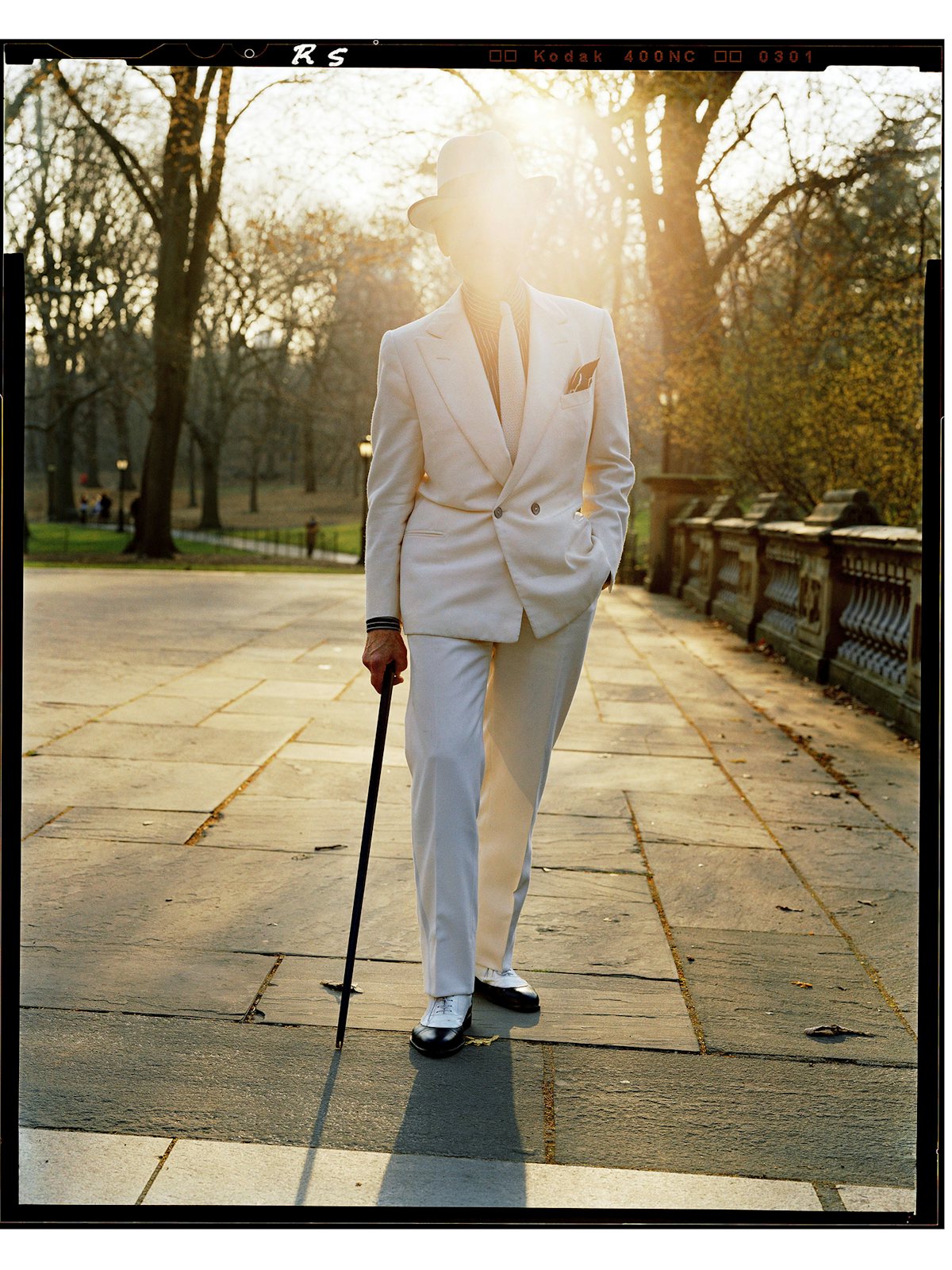

That was to be expected—it was, after all, the first novel by another one of New York’s most famous and outspoken men. And while Tom Wolfe’s profile has diminished in the years since his death in 2018, things are looking up for the legacy of the man in white. His second novel, A Man in Full, will soon be a Netflix series—just a few years after his book The Right Stuff, already the source material for an Academy Award–winning 1983 film, was adapted for television. Wolfe also happens to be the subject of the slender and not so satisfying new documentary, Radical Wolfe, directed by Richard Dewey, which holds few surprises for the viewers likeliest to seek out such a film—those who already know Wolfe’s work and persona well. The wit in white with the whiz-bang prose, a pioneering literary journalist of American lifestyles who found late success, as well as scorn, by writing a journalist’s approximation of literature—this is the Wolfe that emerges from the film and the worshipful 2015 profile by Michael Lewis it is based on, and the image of Wolfe likely to endure in the public imagination.

Yet Wolfe was also, in essence, a theorist of American life—his work was informed by a body of ideas that his pop cultural status has largely obscured, and that he himself downplayed throughout his life. The Wolfe that emerges when one takes those ideas seriously isn’t a “radical” in any meaningful sense, but he is rather more interesting. Behind the ellipses and exclamation points and between the lines of his prose, a lively though often lazy conservative mind was at work, making sense of the half-century that birthed our garish and dismal present, Trump and all.

Tom Wolfe was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1930. His father, an agricultural scientist, was the editor of a magazine called The Southern Planter, which piqued his interest in writing. He enjoyed what was by all accounts a stable and comfortable childhood, and was raised, Lewis tells viewers in Radical Wolfe, to admire “athletes and war heroes.” He especially came to admire folk icons from the South, like Junior Johnson, an ex-bootlegger and one of stock car racing’s earliest superstars, whom Wolfe dubbed “The Last American Hero” in a 1965 piece for Esquire that helped raise NASCAR’s national profile. “He’s drawing the attention of blue America to red America,” Lewis says in the segment on Johnson. In fact, the South was solidly Democratic and thus “blue” in contemporary terms at midcentury, but the inattentive viewer will get Lewis’s point.

As the film tells it, when Wolfe—this affable and earnest cultural ambassador, straight from Dixie—entered Yale’s Ph.D. program in American studies in 1952, he immediately got the cold shoulder from the sons of the East’s elites. “He gets to Yale and all of a sudden he realizes there are all these people who kind of look down on the world he came from,” Lewis says. “But he had such a deep love of where he was from that he started to develop a mild contempt for the people around him.” That contempt eventually found an outlet in his Ph.D. thesis—a study of the League of American Writers in the 1930s, written from what Lewis calls “a vaguely right wing perspective,” though the film only lingers on this interesting tidbit briefly. The experience of writing the thesis and the criticism it received, we’re told, soured Wolfe on academia and sent him toward his first gigs as a reporter. In 1962, after stints at Springfield, Massachusetts’s Springfield Union and The Washington Post, he wound up, inevitably, in New York, where he began writing for the New York Herald Tribune.

The break Wolfe got that year is the stuff of legend among long-form journalists. After a newspaper strike broke out, Wolfe, looking for a freelance assignment, successfully pitched Esquire on a story about the world of hot rods—out in Los Angeles, a teen subculture had emerged around customizing cars for speed and style. But after several weeks reporting the story out in California, he returned wholly overwhelmed by his own material. He wrote nothing. Esquire’s presses, meanwhile, had already printed large color photographs to accompany Wolfe’s story. It had to run. Esquire editor Byron Dobell finally told Wolfe to send along his notes in the hopes that another writer could turn them into a workable article. And in a marathon writing session, Wolfe shaped all he’d collected into a rambling and digressive but detailed 50-page letter. Dobell read it, struck out the greeting and signature, and published it as it was. The title: “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmmm) …” Instantaneously—almost literally overnight—Wolfe became one of the most famous magazine writers in America. The stylistic flourishes and rule-breaking informalities that Esquire’s readers went mad for would only get wilder and more daring in Wolfe’s subsequent writing. Run-on sentences; onomatopoeia; wholly invented punctuation; a torrent of cultural and historical references both high and low; streams of consciousness; shifting perspectives; kaleidoscopic imagery; fashions, furnishings, and other lifestyle markers described in fine and obsessive detail; a tone fluctuating, sometimes within the space of a paragraph, between coolly bemused incredulity and genuinely manic enthusiasm—whether one liked it or not, and many did not, Wolfe was a true original, imbuing features such as his profile of Junior Johnson with something like the spirit of literature.

God! The Alcohol Tax agents used to burn over Junior Johnson. Practically every good old boy in town in Wilkesboro, the county seat, got to know the agents by sight in a very short time. They would rag them practically to their faces on the subject of Junior Johnson, so that it got to be an obsession. Finally, one night they had Junior trapped on the road up toward the bridge around Millersville, there’s no way out of there, they had the barricades up and they could hear this souped-up car roaring around the bend, and here it comes—but suddenly they can hear a siren and see a red light flashing in the grille, so they think it’s another agent, and boy, they run out like ants and pull those barrels and boards and sawhorses out of the way, and then— Ggghhzzzzzzzhhhhhhggggggzzzzzzzeeeeeong! —gawdam! there he goes again, it was him, Junior Johnson! with a gawdam agent’s si-reen and a red light in his grille!

Like Lewis’s 2015 profile in Vanity Fair, Radical Wolfe suggests Wolfe’s style was substantially derived from the casual letters he would send to his parents. “I ended up doing really what a lot of us do in letters, particularly when you’re writing a letter to somebody you feel very comfortable with, someone you can unburden your soul to,” Wolfe once told an interviewer. “And you don’t censor out all of the random remarks that are running through your head. You don’t censor out the slang, you don’t censor out the exclamations, and you don’t censor out the abrupt changes of thought.”

But it hardly seems a coincidence that other journalists started experimenting with the medium at around the same time. Thanks substantially to Wolfe, the term “New Journalism,” a label that had been applied to a variety of new developments in the profession for decades, acquired a specific association with the work of writers like Wolfe himself, his friends and rivals Gay Talese and Hunter S. Thompson, and peers like Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, and George Plimpton—all of whom, in their own ways, were challenging the prevailing strictures and conventions of nonfiction.

Radical Wolfe explains their rise, rather simply, as a product of the era’s sociopolitical and cultural upheavals. “Journalists are rebelling against what everyone else was rebelling against,” Esquire Classic’s Alex Belth explains as a picture of Joan Didion comes up on the screen. “Wolfe and that generation, they’re trying to capture a world that seems to be going faster and faster.” “They were all trying to create an excitement on the page,” Lewis says in another snippet, “and all the things that are changing in America, it’s reflected in kind of the way the prose looks and sounds.”

But there were large and meaningful differences between the approaches and styles the leading lights of New Journalism adopted. While some wrote prose that almost matched the giddy excitement and overstimulation of Wolfe’s, others, Didion chief among them, maintained a placid reserve. Didion’s work also happens to challenge the idea, moreover, that New Journalism was intrinsically a literature of rebellion, motivated or inspired by the major social movements and cultural upheavals of the era. She wrote with a palpable disdain for the American counterculture and even the women’s movement; Slouching Towards Bethlehem, in particular, is a high-resolution portrait of a country beginning to spiral, by her lights, out of control.

As a film about one writer in particular, Radical Wolfe can probably be forgiven for not delving too deeply or convincingly into why New Journalism emerged as a broader phenomenon. It is less forgivable, however, that the documentary sketches Wolfe himself so thinly and offers up little that those familiar with his work wouldn’t already know—he was an arch satirist and an innovative prose stylist, viewers are told, with a fondness for white suits, which the film inevitably lingers on. “I think if you started to get a little famous as a writer in the late 60s, early 70s in the United States, you had some obligation to be a character,” Lewis says. “You could be outrageous like Hunter Thompson, you could be a pseudo- Englishman like William F. Buckley, you could stab your wife like Norman Mailer, and the white suit enabled people to think of him as this great, unusual character.”

Wolfe had an untroubled personal life—one wife of 40 years and two children—and a quiet, reserved personality at odds with his showy and often ribald prose. The suit compensated for that—the lone memorable component, beyond Wolfe’s writing itself, of what Gay Talese, at one point in the film, calls “the facade of being Tom Wolfe.” And it was enough for a time: The 1987 publication of the zeitgeist-capturing New York City novel The Bonfire of the Vanities delivered Wolfe and his white suit into literary stardom with all the fixings—commencement addresses, cameos on The Simpsons, invitations to panels and festivals and late-night shows where he waxed lyrical about the trends and tumults shaping American culture at the end of the twentieth century and The End of History.

But eventually, it all started wearing thin. A Man in Full (1998), his widely anticipated second novel, sold a lot and was forgotten almost immediately. Radical Wolfe passes over his other novels—2004’s I Am Charlotte Simmons and 2012’s Back to Blood—in an embarrassed near-silence. After a perfunctory glance at Wolfe’s widely panned last book, 2016’s The Kingdom of Speech, which attempts a takedown of nothing less than Darwin’s theory of evolution, the film is substantively done, leaving unanswered the question Lewis opens it with—the question he first asked himself at 12 or 13 upon reading Wolfe’s infamous account of Leonard Bernstein’s fundraiser for the Black Panthers, “Radical Chic.” “Even though Tom wasn’t really talking about himself very much, there was this—boom—this personality coming off the page,” he recalls. “And I remember wondering, ‘Who wrote this? Who’s Tom Wolfe?’”

That’s a question best answered by attending more closely to the substance of Wolfe’s writing than Radical Wolfe does.

Though he’ll be remembered as an inventive journalist who managed a moderately successful turn to popular fiction, Tom Wolfe was also a social theorist in natty but thin disguise—his work both espoused a mostly coherent worldview and made a case for a particular way of viewing the world. All told, the bulk of Wolfe’s writing is animated by a conviction that revolutions of style are also revolutions of substance—look closely enough at an aesthetic trend or fashionable consumer fad, he insists excitedly, time and time again, and you’ll find the elements of a social or cultural turn, and perhaps one that’s escaped the attentions of most cultural observers.

His Esquire feature on hot rods, for instance, the piece that brought him to prominence, is more than just the first major showcase for his pyrotechnic prose or an informative and engaging look at youth car culture. It’s an exhortation, one that he’d repeat often, to locate meaning in the putatively superficial—to examine the values underpinning artifice. “I don’t have to dwell on the point that cars mean more to these kids than architecture did in Europe’s great formal century, say, 1750 to 1850,” he wrote. “They are freedom, style, sex, power, motion, color—everything is right there. Things have been going on in the development of the kids’ formal attitude toward cars since 1945, things of great sophistication that adults have not been even remotely aware of, mainly because the kids are so inarticulate about it, especially the ones most hipped on the subject.”

Being articulate about the inarticulable, for Wolfe, demanded the adoption of a now standard critical posture—taking popular culture seriously and viewing its products and developments as worthy of close study, if not respect. Through this lens and in his hands, a figure like Phil Spector, for instance, the twentysomething tycoon savant of early ’60s pop, might additionally be understood as a cultural figure of almost world-historical importance. “Every baroque period has a flowering genius who rises up as the most glorious expression of its style of life,” he wrote in a 1965 profile. “In latter-day Rome, the Emperor Commodus; in Renaissance Italy, Benvenuto Cellini; in late Augustan England, the Earl of Chesterfield; in the sal volatile Victorian age, Dante Gabriel Rossetti; in late-fancy neo-Greek Federal America, Thomas Jefferson; and in Teen America Phil Spector is the bona-fide Genius of Teen.”

Wolfe’s very writing style, and the New Journalism more broadly, reflected this disposition and advanced a then-controversial argument: that journalism—lowly, quotidian writing for the masses, long passed over and sniffed at by the literary world—could be a kind of popular art. And almost immediately after he began drawing major attention, well-regarded authors and critics clambered out of the woodwork to loudly disagree: “the sudden arrival of this new style of journalism, from out of nowhere,” Wolfe recalled proudly in the introduction to his 1973 anthology, The New Journalism, “had caused a status panic in the literary community.”

[A]ll of a sudden, in the mid-Sixties, here comes a bunch of these lumpenproles, no less, a bunch of slick-magazine and Sunday-supplement writers with no literary credentials whatsoever in most cases—only they’re using all the techniques of the novelists, even the most sophisticated ones—and on top of that they’re helping themselves to the insights of the men of letters while they’re at it—and at the same time they’re still doing their low-life legwork, their ‘digging,’ their hustling, their damnable Locker Room Genre reporting—they’re taking on all of these roles at the same time—in other words, they’re ignoring literary class lines that have been almost a century in the making.

Wolfe would spend much of his career identifying and chronicling similar upheavals: the first astronauts, instant celebrities, leapfrogging fighter pilots in the status and honor hierarchy detailed in The Right Stuff; Junior Johnson and stock car racers cruising past a disapproving Southern gentry in public estimation in “The Last American Hero”; pop culture– and Pop Art–adjacent It Girls like Baby Jane Holzer toppling New York’s high society debutantes, as recounted in 1964’s “The Girl of the Year.” “Once it was power that created high style,” he wrote. “But now high styles come from low places, from people who have no power, who slink away from it, in fact, who are marginal, who carve out worlds for themselves in the nether depths, in tainted ‘undergrounds.’”

Gradually, over the course of his career, Wolfe cobbled all this material into a kind of grand theory of American life, one that earns him a place, alongside figures like Thorstein Veblen and Erving Goffman, as one of the most important writers on status and prestige in our society. The central tenet of his social thought was that America’s post–World War II economic boom had delivered the country more prosperity than it knew what to do with. “It has pumped money into every class level of the population on a scale without parallel in any country in history,” he wrote in “The ‘Me’ Decade,” his essay on the 1970s. “In America truck drivers, mechanics, factory workers, policemen, firemen, and garbagemen make so much money—$15,000 to $20,000 (or more) per year is not uncommon—that the word proletarian can no longer be used in this country with a straight face.”

Fatally for the political left, from Wolfe’s perspective, that freedom and plenty for the average American had been produced by capitalism—without a revolution or the social and economic engineering of dour utopian planners. “The new freedom was supposed to be possible only under socialism,” he wrote. It wasn’t supposed to result from “a Go-Getter Bourgeois business boom such as began in the U.S. in the 1940’s.” And “the liberated man” it produced, he pointed out, “didn’t look right.” In personal dress, modesty and humility had been expected; instead, prosperity had decked the American worker out in gaudy fashions. (“$35 Superstar Qiana sport shirts with elephant collars and 1940s Airbrush Wallpaper Flowers Buncha Grapes and Seashell designs all over them.”)

The average American similarly rejected the austere trends in modernist architecture that Wolfe described and derided in 1981’s From Bauhaus to Our House. While the minimalist innovations of figures like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe and the European left’s aspirations for “worker housing” would influence American public housing projects for the poor and, rather ironically, corporate office buildings, the expanding middle class wound up flowing out of the country’s urban centers and tall apartment buildings altogether. They favored “houses with pitched roofs and shingles and clapboard siding,” “the more cute and antiquey touches, the better,” Wolfe observed. They outfitted their suburban homes “with ‘drapes’ such as baffled all description and wall-to-wall carpet you could lose a shoe in, and they put barbecue pits and fish ponds with concrete cherubs urinating into them on the lawn out back, and they parked the Buick Electras out front and had Evinrude cruisers up on tow trailers in the carport just beyond the breezeway.”

Developments like these left America’s social critics in a pickle. Wolfe argued that American thinkers—eager to maintain their relevance and match the seriousness and gravity of European intellectuals who had their countries helpfully ravaged, with some regularity, by violent conflict—actively ignored the country’s rising prosperity in favor of issuing ponderous and overly pessimistic declamations against wealth inequality, structural racism, government abuses, and other social ills. The disorders of the late 1960s, he contended, had been actively welcomed and relished. “There were riots on the campuses and in the slums,” he wrote. “The war in Vietnam had developed into a full-sized hell. War! Revolution! Imperialism! Poverty! I can still remember the ghastly delight with which literary people in New York embraced the Four Horsemen. The dark night was about to descend.”

Instead, for most Americans, the angst of the late ’60s eventually gave way, despite the best efforts of the country’s leading buzzkills. In one 1976 essay, Wolfe recounts following another writer’s disquisition on the state of American society with an impolitic remark during a campus speaking appearance. “Suddenly I heard myself blurting out over my microphone: ‘My God, what are you talking about? We’re in the middle of a … Happiness Explosion!’”

The “Happiness Explosion” scattered new lifestyles and subcultures for Wolfe to cover across the country in all directions—the surfers of Southern California; Hugh Hefner and the swinging playboys who emulated him; stock car racers, hot-rodders, and demolition derby drivers enthralled by that shining emblem of American postwar plenty, the automobile. These new “statuspheres,” as Wolfe called them, allowed Americans to overcome or subvert old social hierarchies—they came with their own rules and allowed those within them to succeed, culturally, on their own terms.

No statusphere or subculture fascinated Wolfe more than the world of the hippies, the subject of his 1968 classic, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. The literary dropout Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters were, to Wolfe, more than just a roving troupe of LSD-addled hedonists. They were an ecstatic, distinctively modern, and distinctively American religious cult, made possible by capitalism’s bounty and the scientific and technological advances underpinning the production of LSD and psychedelic art—a “true mystic brotherhood” that had taken root “in poor old Formica polyethylene 1960s America without a grain of desert sand or a shred of palm leaf or a morsel of manna wilderness breadfruit overhead, picking up vibrations from Ampex tapes.”

While Kesey and his followers saw themselves as outcasts from mainstream society and crisscrossed the country in a bus trying to trip-out and turn-on the squares, Wolfe framed the hallucinatory highs they experienced on acid as mere extensions of an already phantasmagoric American reality— outgrowths of the surreal freedoms and pleasures available to ordinary Americans in the suburbs Kesey himself had come from. (The “world of Mom&Dad&Buddy &Sis in the suburbs” was already full of futuristic luxuries, like the family car in the driveway—a “crazy god-awful-powerful fantasy creature” with “327 horsepower.”)

But Wolfe’s genuine fascination with the hippies was mixed with a sniggering incredulity and even disgust at their antics. Like Didion, Wolfe came away from San Francisco in the late 1960s convinced that the center wasn’t holding in Haight- Ashbury or America at large. While Acid Test is often framed and remembered—even in Radical Wolfe—as a celebration of the counterculture, Wolfe’s actual disposition toward the hippies is laid bare in passages like his account of the fate of “Stark Naked,” a Prankster who’d taken to wearing nothing or next to it and had seemingly melted her brain into a warm paste on LSD. At one of the stops on the tour, she mistakes a stranger’s young son for her “own divorced-off little boy” and runs naked and shrieking toward him. Stark Naked, Wolfe concludes, “had completed her trip. She had gone with the flow. She had gone stark raving mad.”

While the postwar boom had materially improved the lives of most Americans, Wolfe also believed that the freedom and prosperity they enjoyed had bred cultural confusion—as exemplified by the hippies. “THE ‘ME’ DECADE AND THE THIRD GREAT AWAKENING,” for instance, is a breezily written but substantively grave assessment of the excesses and narcissistic indulgences Wolfe believed were corroding American life—easy sex, consumerism, and the phony, self-centered spiritualism driving a “Third Great Awakening.” “All rules are broken!” he wrote. “The prophets are out of business! Where the Third Great Awakening will lead—who can presume to say? One only knows that the great religious waves have a momentum all their own. Neither arguments nor policies nor acts of the legislature have been any match for them in the past. And this one has the mightiest, holiest roll of all, the beat that goes … Me … Me … Me … Me …”

Wolfe ends the piece with a then- uncharacteristically serious and direct push for his readers to reject “the luxury, enjoyed by so many millions of middling folk, of dwelling upon the self” and embrace the elemental realities their forebears had. Soldiers laying their lives on the line for their country and parents willing to sacrifice “their own ambitions and their material assets” were, for Wolfe, role models the country should return to, people who understood their lives “however unconsciously, as part of a great biological stream.”

The Right Stuff (1979), Wolfe’s book on the first American astronauts, the Mercury Seven, can be read as an exploration of the virtues Wolfe wanted more Americans to adopt. The right stuff that John Glenn and Alan Shepard exemplified was something more than mere bravery or moxie. It was the capacity to genuinely improve oneself—not through narcissistic introspection or consumption, but by taking on “a seemingly infinite series of tests.” And what the Mercury Seven demonstrated, he suggested, was that the task of self-improvement might ideally be undertaken “in a cause that means something to thousands, to a people, a nation, to humanity, to God.”

It should perhaps go without saying at this point that Wolfe was a conservative. This is obvious enough in his writing that Radical Wolfe’s reticence about his politics is striking and curious. “He sat at a very uncomfortable intersection between red America, blue America, left and right,” Lewis says unhelpfully at one point. “He avoided being too closely identified with any kind of political ideology.” This was true of many of Wolfe’s interviews and public statements, but his writing simply wasn’t as open to ideological interpretation as the film suggests. Its very first overt statement on Wolfe’s political thought comes from The Wall Street Journal’s Gregory Zuckerman, who argues, “in some ways, he’s very much progressive, in that he’s very focused on those overlooked in society.”

At a stretch, this might describe Wolfe’s interest in midcentury subcultures, yes. But he’s known just as well for the obsessive, critical attention he paid to the affluent and cultural elites—the contemporary art world and its clueless patrons, the yuppies of ’80s Manhattan, the literary royalty of The New Yorker, who drew a telephone call from the White House in their defense after Wolfe skewered the magazine in a still-hilarious pair of 1965 essays.

Most of those elites nevertheless fêted and celebrated him for most of his career. If Wolfe minded playing the role of an uncommonly skilled, white-costumed jester in their court, he never showed it; in turn, his well-to-do subjects rarely took the substance of what he said too personally or too seriously. “The strange thing in his life is that while every now and then someone would challenge him in a review on political grounds, most of the New York literary establishment just loved him,” Lewis says. “They loved him personally, they loved what he wrote. And they kind of thought of whatever his political views were as beside the point. And I kind of think they were.”

But the notion that Wolfe’s politics were inscrutable and irrelevant is undermined substantially by the presence of one of Radical Wolfe’s most prominent talking heads. Late in the film, Peter Thiel—the billionaire co-founder of PayPal, Republican megadonor, and part-time commando in the culture wars—appears like a jump scare to deliver some of its most vapid lines. “It’s almost impossible for someone to do what Tom Wolfe did in our society today,” he says at one point. “It’s been impossible I would say for probably close to 40 years.” Of course, one counterexample to the idea that it’s been impossible to do what Tom Wolfe did for the last 40 years was the career, over the last 40 or so years, of one “Tom Wolfe.” And if taking a scalpel to elites the way that Wolfe did has gotten harder, that surely has at least a little to do with the dispositions of affluent men like Thiel, who bankrolled the lawsuit that shuttered Gawker, one of the last refuges in the press of Wolfe’s puckish, impudent spirit.

But on the matter of ideology, and as Thiel clearly perceives, Wolfe and Thiel were simpatico. That’s made especially plain by Wolfe’s Yale dissertation, which is, again, only briefly mentioned in Radical Wolfe. At over 300 pages, “The League of American Writers: Communist Organizational Activity Among American Writers, 1929–1942” should, by all rights, be considered one of Wolfe’s major works. And as he bitterly complained at the time, he was forced to substantially revise an initial draft of it. “These stupid fucks have turned down namely my dissertation,” he wrote in a letter, excerpted in Lewis’s Vanity Fair profile. “They called my brilliant manuscript ‘journalistic’ and ‘reactionary,’ which means I must go through with a blue pencil and strike out all the laughs and anti-Red passages and slip in a little liberal merde, so to speak, just to sweeten it.”

The surviving final dissertation contains many of the ideas he would return to again and again during his career. It was status competition and anxiety in New York’s literary set during the 1930s, Wolfe argued, that allowed so many writers to become unwitting dupes of the Communist Party—laying the groundwork, he alleged, “for a monolithic, Communist-controlled writer- bureaucracy covering the entire American writing craft” that, fortunately, never came to pass. Some of the tactics the Communist Party used to bring writers into its fold were as simple as providing venues where writers could interact socially—including fundraisers for generically progressive, and not overtly communist-aligned causes. “The Communist organizers in charge were always careful to see to it that the liquor was, indeed, ample.” Once the guests were “steeped in alcoholic spirits and entertainment,” they would lose the ability to distinguish between “the conventional cocktail party symbols of literary status” and “the political symbols and ideology embodied in the cause.” In no time, they’d be making donations.

Wolfe reviled Marxism and the radical left for the entirety of his life. Repeatedly in his writings, he makes reference to the work and claims of the Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who, he wrote in a 1976 essay, had demonstrated that “tens of millions” had been killed in Russian gulags, making it “impossible any longer to distinguish the Communist liquidation apparatus from the Nazi.” (It’s thought today that under two million died in the gulags.) And it’s hard to imagine the parties writers of the old left threw weren’t on his mind as he penned his most notorious nonfiction piece, his account of Leonard Bernstein’s fundraiser for the Black Panthers, “Radical Chic.”

In January 1970, Bernstein hosted a party at his Park Avenue penthouse apartment to raise funds for the legal defense of 21 members of the Black Panther Party, who were accused and later fully acquitted of a bomb plot. The assembled luminaries, including Barbara Walters, the director Otto Preminger, the photographer Richard Avedon, and New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers, rubbed shoulders, eating “Roquefort morsels” as they discussed social justice. Wolfe’s report on the proceedings is, even today, a devastating read, chock-full of the kind of glittering ironies and hypocrisies he collected like a magpie. In one scene that calls Jordan Peele’s Get Out to mind, Bernstein, patronizing throughout, tries to empathize with Panther Don Cox, who Bernstein thinks is put off by his wealth. “When you walk into this house, you must feel infuriated!” Bernstein tells him. “Don’t you get bitter? Doesn’t that make you mad?” Cox insists he’s fine, but Bernstein presses on: “Having this apartment makes this meeting possible, and if this apartment didn’t exist, you wouldn’t have it. And yet—well, it’s a very paradoxical situation.”

The situation might have been even more nakedly paradoxical at the other radical fundraisers then sweeping New York high society if cautious hosts hadn’t, as Wolfe relates, gone out of their way to replace their Black servants so as not to offend the Black Panthers and other minority guests. “Obviously you can’t have a Negro butler and maid, Claude and Maude, in uniform, circulating through the living room, the library and the main hall serving drinks and canapés,” he writes. “So the current wave of Radical Chic has touched off the most desperate search for white servants.” Going without servants altogether, Wolfe emphasizes, was out of the question. (“Why, my God! servants are not a mere convenience, they’re an absolute psychological necessity.”)

Wolfe wasn’t skewering wealthy liberals from a position of ideological impartiality, as much as he suggested otherwise in interviews. He considered the left naïve, if not dangerous, on economics, and seemed willfully blind to the gradual erosion of the middle-class stability and prosperity he’d documented. He was troubled less by the political economy of rising inequality than by the extent to which it corroded traditional values and enabled social progressivism. His disdain for the sexual revolution didn’t prevent him from crudely ogling at and objectifying women—and even girls, like the “beautiful little high-school buds in their buttocks-décolletage stretch pants” he describes in an essay on Las Vegas. His references to homosexuality don’t read much better: One particularly bizarre late- career short story, “Ambush at Fort Bragg,” frames three soldiers who had murdered a gay serviceman as victims of liberal- media condescension. And pieces like “Radical Chic” in particular surfaced another undercurrent of his work that would only become more central and prominent as his career wore on.

Reading a Wolfe piece for outright racism is a bit like watching a cocky acrobat on a tightrope. He struts and sways dangerously; now and again he does, in fact, fall off. Radical Wolfe treads cautiously around the subject, as does Lewis’s Vanity Fair profile, though Lewis can’t help but mention, in the latter, that one of Wolfe’s letters to his parents from his time working in Washington, D.C., describes one street lined with African embassies as “Cannibals Row.” Most of his writing isn’t quite that crude. But what might charitably be called a pessimism about the possibility of racial harmony is present throughout his work.

In 1970, “Radical Chic” was paired off and published as a book with another Wolfe essay called “Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers,” an account of confrontations between poor minorities and the hapless bureaucrats, or “flak catchers,” managing social programs at the Office of Economic Opportunity in San Francisco. As Wolfe understood it, the planners behind the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, part of the Johnson administration’s “War on Poverty,” had intentionally encouraged militant organization in community groups as a means of distributing jobs and economic aid. “Instead of handing out alms, which never seemed to change anything, they would encourage the people in the ghettos to organize,” he wrote. “They would help them become powerful enough to force the Establishment to give them what they needed. From the beginning the poverty program was aimed at helping ghetto people rise up against their oppressors. It was a scene in which the federal government came into the ghetto and said, ‘Here is some money and some field advisors. Now you organize your own pressure groups.’”

But in practice, Wolfe claimed, the community initiatives that came out of the Economic Opportunity Act did little more than encourage radical groups and street gangs to come together and intimidate or “mau-mau” bureaucrats with the threat of violence—“mau-mau” being a reference to the indigenous rebels who battled the British in Kenya during the 1950s. “If you could make the flak catchers lose control of the muscles around their mouths, if you could bring fear into their faces, your application was approved,” he claimed. “Ninety-nine percent of the time whites were in no physical danger whatsoever during mau-mauing. The brothers understood through and through that it was a tactic, a procedure, a game. If you actually hurt or endangered somebody at one of these sessions, you were only cutting yourself off from whatever was being handed out, the jobs, the money, influence. The idea was to terrify but don’t touch.”

It should go without saying that efforts at physical intimidation were not, actually, representative of the community organizing that grew out of the Economic Opportunity Act. But Wolfe was no policy analyst—he was captivated, instead, by the drama of the isolated scenes he witnessed, recording certain details that revealed more about himself than they did about the people he described, like San Francisco’s Samoan immigrant community. “The average Samoan makes Bubba Smith of the Colts look like a shrimp,” he wrote. “They start out at about 300 pounds and from there they just get wider. They are big huge giants. Everything about them is wide and smooth. They have big wide faces and smooth features. They’re a dark brown, with a smooth cast.” All of this, naturally, factored into Wolfe’s broader breakdown of the races that white bureaucrats feared the most. “Whites didn’t have too much fear of the Mexican-American, the Chicano,” he wrote. “The notion was that he was small, placid, slow, no particular physical threat—until he grew his hair Afro-style, talked like a blood or otherwise managed to seem ‘black’ enough to raise hell. Then it was a different story. The whites’ physical fear of the Chinese was nearly zero.”

This is the very same superficial lens through which Wolfe would view racial divisions in his fiction. The prologue of The Bonfire of the Vanities finds the mayor of New York despairing about the city’s changing demographic makeup and the determination of affluent whites to ignore it in a stream of consciousness as he’s heckled offstage before an audience in Harlem.

Come down from your swell co-ops, you general partners and merger lawyers! It’s the Third World down there! Puerto Ricans, West Indians, Haitians, Dominicans, Cubans, Colombians, Hondurans, Koreans, Chinese, Thais, Vietnamese, Ecuadorians, Panamanians, Filipinos, Albanians, Senegalese, and Afro-Americans! Go visit the frontiers, you gutless wonders! Morningside Heights, St. Nicholas Park, Washington Heights, Fort Tryon— por qué pagar más! The Bronx—the Bronx is finished for you!

In a 1989 essay, Wolfe predicted that “within ten years political power in most major American cities will have passed to the nonwhite majorities,” a state of affairs that would make it harder for the writer to discern “what truly presses upon the heart of the individual, white or nonwhite, living in the metropolis in the last decade of the twentieth century.’”

Wolfe would pursue that theme in three out of his four novels, each of which finds central characters thrust into racialized moral dilemmas complicated by their own status anxiety, the forces of urban politics, and the primordial racial prejudices that, for Wolfe, fundamentally structure urban life. In The Bonfire of the Vanities, Sherman McCoy, a wealthy white bond trader, descends into a legal nightmare and social crisis stoked by a media-savvy Black minister after he and his mistress hit and gravely injure a Black youth they believe might rob them during a detour into “the jungle” of the Bronx; Wolfe’s New York is a powder keg ready to explode. So is his Atlanta. In A Man in Full, Charlie Croker, a boorish and deeply indebted white real estate developer on his second marriage and the cusp of bankruptcy—a country-fried Donald Trump, essentially—is offered a way out of his financial woes if he speaks out in the defense of a Black football star accused of raping the white daughter of another prominent businessman.

In Wolfe’s last novel, Back to Blood, Nestor Camacho, a Cuban American cop, deals with the fallout from his community after he both rescues and arrests a Cuban asylum-seeker at sea, preventing him from becoming an American citizen. But Wolfe’s Miami is also, of course, a powder keg ready to explode, particularly after—in passages that are both prescient and more unsettling now than they would have been in 2012—Camacho puts an unarmed Black man in a choke hold, a confrontation captured on video and posted to YouTube. Camacho is “mesmerized” by watching the scene play back on his laptop: “the brute’s face is twisted beyond recognition—from the pain! His mouth is open. He wants to scream. But he wants oxygen more.… Sounds like a dying duck. Yeah!” In the moment he feels “an adrenal rush immensely more powerful than all chains of polite conversation,” a “vile revulsion comes surging up his brain stem from the deepest, darkest, most twisted bowels of hatred.”

A collapse of faith and an absent sense of purpose, one character suggests in the novel’s prologue, has encouraged minorities to fall “back to blood” and their ethnic ties: “Religion is dying … but everybody still has to believe in something,” they muse. “So, my people, that leaves only our blood, the bloodlines that course through our very bodies to unite us.” Nowhere in the hundreds of pages Wolfe devotes to the subject across his work does he suggest that there might be a collective way out of this. Instead, Wolfe literally sketches out, in a cartoon featured in a 1980s collection of short writing and caricatures, a picture of perpetual tension and separation. “The Melting Pot” depicts a white man and a Black man—the latter thick-lipped and Afro-headed—on leashes. They are nude and baring their teeth—dogs, snarling viciously, raring to rip each other apart.

Radical Wolfe implies strongly that Wolfe and his writing have been victims of changing mores, but Wolfe fell off in estimation and prominence late in his life less because the literary world was offended by him than because it had grown bored with him, and with good reason. In 2000, Wolfe attempted to capture the spirit of the new millennium in his nonfiction anthology, Hooking Up. “American superiority in all matters of science, economics, industry, politics, business, medicine, engineering, social life, social justice, and, of course, the military was total and indisputable,” he wrote, speculating, despite the depth of our racial and cultural divisions, that the close of the “First American Century” might have been just the first chapter in “a Pax Americana lasting a thousand years.” While one can’t exactly blame Wolfe for not anticipating 9/11 and all that would follow it, spending the early 2000s at work on I Am Charlotte Simmons, a turgid and sensationalistic novel about sex on campus, was an odd choice and not one that helped endear him to posterity. By the time Back to Blood rolled around eight years later, Wolfe had essentially vanished from the cultural conversation, save the odd bit of praise for George W. Bush.

He did, of course, live long enough to see the central, real-world character of Bonfire’s New York ascend to the presidency—and to receive undoubtedly constant requests for comment on that fact. But Wolfe had remarkably little to say about Trump’s rise. “I’m struck by the weakening of decision-making in America,” he told a French interviewer in 2017. “This collapse is happening at a time when human and financial losses are mounting— war, economic crisis—but above all it’s an issue of identity and ethics. Should we be outraged, or should we observe? I prefer the second option by far. A writer isn’t there to say what’s good or bad. He’s there to say what is.”

By this rather inane standard, Wolfe wasn’t especially good at writing. Though his ideological commitments were often not explicit early on, his renderings of “what was” were riven with aesthetic, moral, cultural, and political judgments, often condensed within the space of a single observation.

Had he found it in him to say more about Trump, he might have observed that his presidency represented the apex of the social-climbing hedonism he spent most of his life documenting; the status and racial anxieties that were his constant subjects found their ultimate expression in the political rise of a man whose politics are exactly as outrageous, dumb, and showy as his sense of decor. A more thoroughgoing Wolfe would have delighted in showing us why the golden bathroom fixtures mattered; he might have insisted rightly that we ought to take a magnifying glass to the sunbaked minor millionaires and television-addled retirees who make up the clientele at Mar-a-Lago and Trump’s golf courses. One simply cannot understand what has happened to the Republican Party and our politics overall these last 10 years without taking a Wolfian glance at the aesthetics and material aspirations of the right that Wolfe himself, being a conservative, was reluctant to take.

Still, Wolfe’s work has much of interest to say to us now. He held a conviction, particularly in his early career, that the good and bad in American life were better shown, in wild and splendid color, than argued or told. This conviction produced journalism of real and enduring value. While his fiction and later nonfiction were heavy with flat, broad stereotypes, Wolfe was capable of being nuanced and incisive on matters of identity. “The wealthy,” “the youth,” “men,” “women,” and “people of color” were, for Wolfe at his best, not cohesive blocs to freely generalize about, as we’re given to today, but messy amalgamations—collections of sub- groups and subcultures worthy of our curiosity and close attention.

His obsession with aesthetic details not only enlivened his narratives but also imbued them with much of their very substance. Assessments of style and lifestyles, he suggests, can aid us in mapping the differences within and between America’s peoples with precision. While thinking abstractly about, say, the one percent as a category is useful, one leaves Wolfe with a perhaps exploitable understanding of the cultural, generational, and professional divides that shape the world of the very wealthy. For we are defined, he reminds us, not only by the raw categories that we belong to but by our tastes and aspirations. His attention to how we dress and the things we buy was animated by the belief that who we are is, in large part, a function of what we do and seek out at our leisure. This is why Wolfe’s work itself remains worth seeking out—the man, in full, wrote with a style, verve, and perspective that, for better or for worse, American journalism will not likely see again.