It takes some daring to choose opium as your historical protagonist. The milky sap of the poppy flower has taken so many forms across so many centuries that its allure feels like a trap, a chasing of the dragon as risky for the historian as the casual user. Like cannabis, its rival for the title of most venerable medicine and psychoactive, opium is indeterminate. A sedative with stimulant properties, it was cultivated, trafficked, and prized for millennia as a salve to suffering, aid to sleep, and courtly gateway to euphoric visionary states. This long opening act would appear one-dimensional following its modern reinvention as a commodity of empire, currency of covert ops, and ancestral shape-shifter behind an endlessly compounding addiction pandemic. When writing about the historical force of plants, any other flower will prove more cooperative, if duller, than Papaver somniferum.

The novelist Amitav Ghosh approaches his subject with the proper respect in Smoke and Ashes, a sensitive, ambitious, and layered work that occupies a middle ground between global plant history and academic case study. Generations of scholarship on the nineteenth-century opium trade have been marked by lopsided attention to the English and Chinese, in particular the two Opium Wars. Smoke and Ashes synthesizes and builds upon a revisionist wave of research focused on opium’s deep markings on Indian culture and development. Its subject is the industry around the white poppy flower that the East India Company cultivated for more than 150 years across India’s Gangetic plain, the base of a triangular trade that paid for much of the Raj’s administrative costs. Ghosh comes to the task with a parent’s pride, citing evidence that his Ibis Trilogy of historical novels helped inspire a wider corrective turn among scholars. “It is vanishingly rare,” he writes, “for the circular pathways between historical fiction and academic historiography to be publicly acknowledged.”

He begins his story in a porcelain cup. A century before the East India Company began flooding China with opium, China hooked the English on a hot caffeinated drink they called cha. It was on tea levies that the Company grew rich and funded its early expansion. Unfortunately for it and its London sponsors, demand for Chinese tea surged even as the output of New World silver mines began to wane. Since bullion was the only thing that interested the Chinese, the British found themselves on the edge of a balance-of-payments cliff. It was an engineer and shipbuilder named Colonel Watson who, at a 1767 meeting of the East India Company board in Calcutta, proposed countering the Chinese tea monopoly with an English opium monopoly. But not just any opium. At the center of the plan was a relatively new, highly concentrated, and more easily smoked form of opium called chandu.

The English turned to the Dutch East India Company for inspiration. For decades, the Netherlands had been using opium to grow and consolidate its Javanese empire. In classic dealer fashion, the Dutch began by gifting chests of opium to local powers, seeding the market for an opium monopoly it protected by waging mini opium wars across the archipelago. The result was the Netherlands’ emergence as what Ghosh calls “the world’s first imperial narco-state.” The spoils were distributed back in Amsterdam through the Dutch Opium Society, whose charter members included the firms today known as Royal Dutch Shell and BHP Billiton, the mining giant.

It was in Javanese ports that Chinese sailors learned the habit of smoking tobacco dipped in Dutch-made liquid opium. They brought the practice back to Chinese port cities, where opium dens proliferated, leading the Emperor to ban the drug in 1729, the first of many failed attempts to stomp out its use in the Celestial Empire. By the time the Company decided to scale the Dutch model with the more addictive chandu, writes Ghosh, “the practice of using opium as a currency had acquired a lengthy pedigree in European colonial practices, and all the elements of the emergent system had already been in place for almost a century.”

Industrializing poppy production in British-occupied India required two novel developments: vast land conversion and the creation of a labor army disciplined by the regimented logic of the plantation. The transformation of the peasant economy was swift and calamitous. By forcing the farmers of Bengal and Bihar to produce opium at a loss, the British created an agricultural underclass without traditional means of sustenance. “Farmers could be evicted if they planted any other crop, and since most poppy growers were ‘tenants at will,’ they were in constant danger of losing their land,” writes Ghosh. Research suggests the large-scale conversion of paddy to poppy fields contributed to the Bengal Famine of 1770.

By 1830, the Company’s poppy fields comprised what Ghosh calls a “kingdom within an empire” stretching from Agra in north-central India to Bengal’s border with China. Within this kingdom, up to half of the population was working for an opium operation that historians consider to be the world’s first modern end-to-end drug cartel. Ghosh, who traces his family history back to the opium production hub of Bihar, powerfully reconstructs the systems of surveillance and control overseen by the Company’s Opium Department and its seemingly infinite regression of ranked “Sub-Deputy Opium Agents” and “Assistant Sub-Deputy Opium Agents.” The Company’s punitive apparatus reached beyond farmer households and transformed the fabric of village life. Neighbors and local passersby were forbidden from coming near the fields at harvest time; those who did who were subject to search, seizure, and punishment on the mere suspicion of pilfering precious poppies. “Our prayer is that we may be released from this trouble,” read a representative petition from hundreds of farmers in India’s opium heartland.

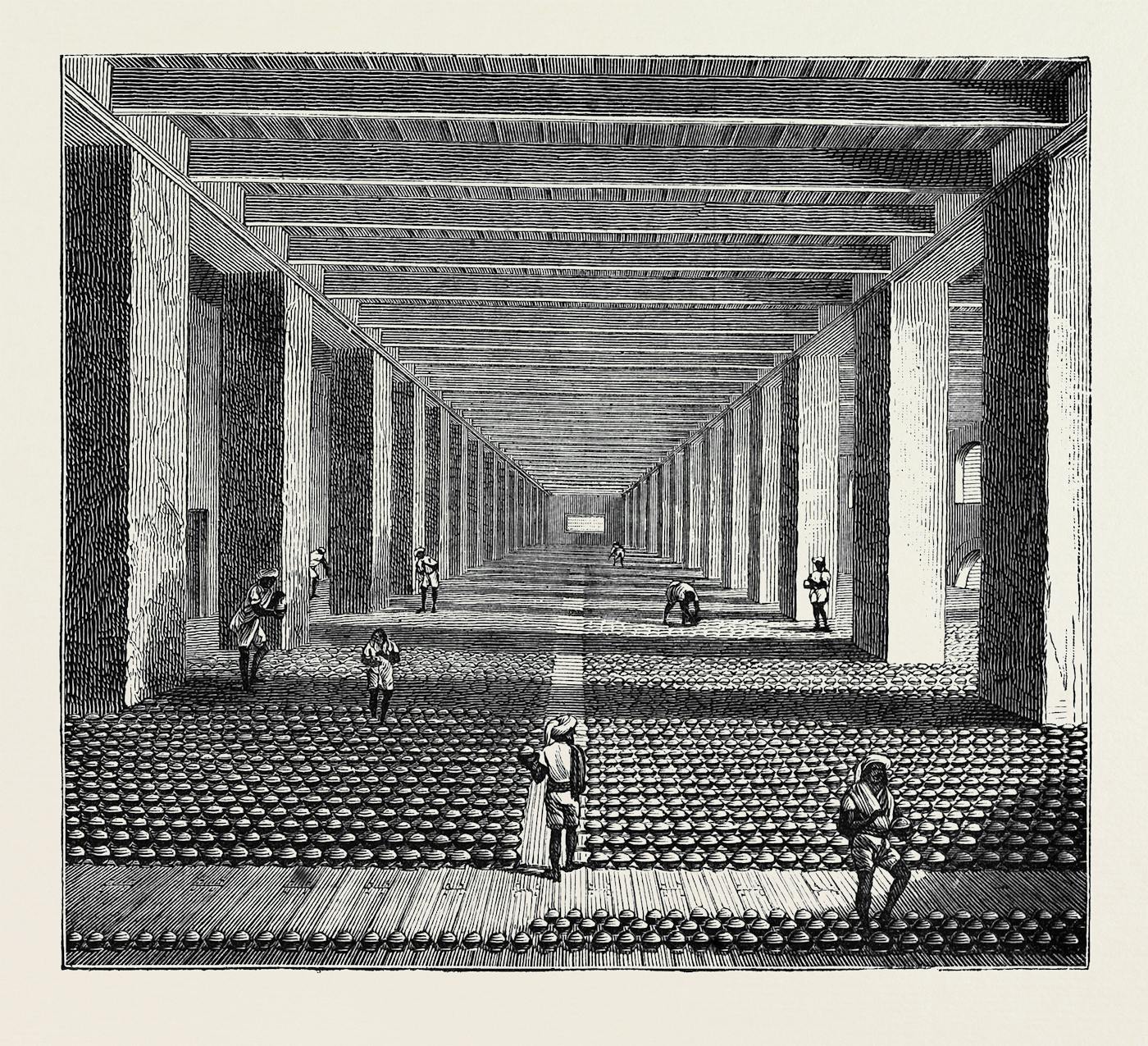

Some of the strongest and most meticulously constructed sections of the book concern the two citadel-like factories in Patna and Varanasi where raw opium gum was processed into wholesale slabs of chandu. Constructed during the 1780s, the twin factories’ assembly lines and stringent production quotas anticipated Taylorist systems of scientific management, but bore little relation to depictions in the British press showing them as gleaming emblems of progress and development. Barefoot workers “spent as much as ten hours a day tramping up and down long vats of raw opium,” writes Ghosh. “Far from being clean, Euclidean spaces, the factory’s interiors were crowded, hot and cramped, with hundreds of men and boys laboring under the eyes of their white overseers.” It is no surprise, he notes, that the factory zones emerged early as hotbeds of revolt during the 1857 uprising against British rule.

Colonel Watson’s plan soon exceeded the East India Company’s most salivary hopes for the Chinese opium trade. When Queen Victoria assumed the throne in 1837, on the eve of the first Opium War, anxiety over the balance of trade had seesawed from London to Beijing, where Chinese officials fumed about the social impacts of the growing opium market and directed the emperor’s attention to its annual drain of 20 million pounds sterling from imperial reserves. By midcentury, opium amounted to more than half of China’s total imports and represented the British Raj’s third-largest revenue stream after salt and land taxes. The trade crested in 1880 with the delivery of 105,000 chests of chandu to southern Chinese ports. “No single economic policy has ever been more successfully implemented,” concludes Ghosh.

Though the Opium Wars could be considered Sino-Indian wars—most British troops were sepoys—Ghosh wisely avoids spending much time going over their well-trodden grounds. He instead details the lesser-known story of how the British fought and ultimately accommodated the rise of a rival opium industry in western India. After trying and failing to stop independent traders from shipping non-Company-grown opium out of Goa, Karachi, and Bombay, the Company eventually settled for a piece of the action in the form of transit duties.

The result was a thriving twin industry headquartered in Bombay that contrasted sharply with the Company monopoly based in Calcutta. Operating outside the Opium Department’s enervating regimes of inspection and control, and free to negotiate prices with competing traders, western poppy farmers made two to three times more than their impoverished counterparts in the east. In the west, decades of opposition “succeeded in keeping a significant part of the gains of the opium trade out of British hands,” writes Ghosh. The democratic nature of the western trade extended to a bustling speculative bazaar in opium futures that in Ghosh’s telling sounds like online sports betting today. “Every cook’s servant was speculating in this drug,” noted an Indian who traveled to Bombay in 1845. Among those who took full advantage of opium’s Wild West were fortune-seeking Americans like Robert B. Forbes and Warren Delano Jr., two of many who laid the foundations for dynastic wealth by unloading bricks of non-Company opium at ports and smuggling hubs along southern China’s Guangdong coast.

A comparison of these two opium economies forms the heart of the book’s compelling development thesis. Before the imposition of wide-scale opium production, the east was relatively prosperous, as evidenced by the nickname “Golden Bengal.” Following the infliction of opium, eastern India remains defined by underdevelopment and social conflict more than 70 years after independence. The legacy is most pronounced, argues Ghosh, in former poppy-growing areas, which “have had significantly worse long-term social and economic outcomes” than nearby districts. In the shadow of this history, it is only natural that Calcutta emerged from independence to become the country’s center of left-wing economics, and Bihar, its shorthand for feudal inequality, revolutionary politics, and caste violence. Karl Marx does not appear in Smoke and Ashes, but its analysis of opium’s long-term impacts in India offers a mirror-image confirmation of Marx’s prescient analysis that the opium trade, enforced through a humiliating military defeat, would act as a spur to China’s modernization and, perhaps, eventual embrace of Communist principles. Ghosh is on softer ground when he expands this frame to explain every aspect of contemporary life in east India, such as his speculation that it was opium, rather than the vicissitudes of call center outsourcing, that fixed Calcutta on a course to become India’s scam hub.

Throughout Smoke and Ashes, Ghosh is finely attuned to the ways the concept of

“agency,” much like opium, can take different forms and serve different

purposes. The British, for example, became adept at highlighting the

pathologies of Chinese “demand” as a way to deflect responsibility for creating

an addiction epidemic by manipulating supply. In the British press, the Chinese

were rendered eager customers driving the opium market through consumer choice;

if anything could be blamed, it was not the Company, but the “social depravity and deficient

self-control” that was intrinsic to “Asiatic” races. When this narrative failed

to silence growing calls in Britain and China to end the opium trade, editorialists

and pamphleteers made Kiplingesque appeals to those most high, most benevolent, and most unstoppable of agents—History and Progress. The result was a tautological

self-justification that could and did excuse any crime committed in its name. The

British Empire, as the

“Church Militant of the cult of Progress,” viewed the opium trade as “inevitable,

indeed a historical necessity,” writes Ghosh, because it provided the funds “to

go about the business of converting its subject peoples to the worship of

Progress.”

The book’s most provocative discussion of agency involves opium itself. Along with faith in History and Progress, the opium trade reflected the age’s thoroughly rationalist understanding of nature as little more than a storehouse of inert resources. Here Smoke and Ashes makes its second revisionist turn and embraces a twenty-first-century approach to plant history that treats its subjects as active and even conscious agents. Plants are living entities “continuously evolving and finding new modes of articulation … whose intelligence, patience and longevity far exceed that of humans,” writes Ghosh. What is true of plants in general is perhaps even more so for the poppy flower, “one of the most powerful Beings that humans have encountered in their time on earth,” whose interactions with us “are mysterious, sometimes benign and sometimes vengeful.”

This language has begun to influence even in the most hardheaded precincts of plant history. The U.S. State Department’s historian for special projects, William B. McAllister, similarly describes opium in language usually reserved for people, as an “independent biological agent [that has] bested all its human contenders.” Yet as loudly as Ghosh endorses this new paradigm, he’s not quite sure how to practice it. The lack of a developed lexicon for describing “the agency of non-human entities,” he writes, is “disorienting” and makes human-opium interactions “difficult to conceptualize.”

But there’s no need for concepts where some description will do. The science of how opiates communicate with the human brain is advanced, and the richness of the opiate addiction literature, legend. A bit of the latter especially would have added texture to Ghosh’s thesis about opium’s singular power and cunning, and done so without recourse to anachronism. The first dope memoir, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, was published in 1821, the midpoint of the book’s chronology. It not only offers a poetic preemptive rebuke to George Orwell’s later claim, cited deferentially by Ghosh, that the opium high is “indescribable”; it also represents an early expression of the idea that opium demands from us a species-level humility.

“Not the Opium-eater, but the opium, is the true hero of the tale, and the legitimate center on which the interest revolves,” De Quincey writes in Confessions. “The object was to display the marvelous agency of opium.”

Ghosh observes in conclusion that opium and its descendants have never been busier. They are the chaos agents fueling addiction wildfires from Pennsylvania to Pakistan and the merciful providers of peace on the modern deathbed. One wishes, however, that Smoke and Ashes had ended on these notes of fact, and not with the idea that nineteenth-century anti-opium reformers serve as a hopeful example for today’s movement to ban fossil fuels. If your goal is to inspire the global eradication of a wildly profitable trade, the history of opium probably isn’t the one you’re looking for.