Of the neologisms coined by early nuclear strategists to plan for World War III, “overkill” is the great crossover success. As a metaphor, it ranges as far from its original context as a word can—“The pony on her birthday was overkill”—but from common usage a child can intuit its first meaning as applied in nuclear war-fighting: When you can obliterate a city with 10 megatons, it’s excessive to use 20 or 200 megatons. As the firepower of Cold War arsenals began to exceed that required to destroy any conceivable list of enemy silos and cities, sometime in the mid-1950s, overkill went from being a technical factor used in target selection, to a description of the entire East-West face-off, which for three decades resembled a contest devised in the game room of an asylum, with teams vying to achieve the highest possible factor of apocalyptic redundancy. In 1986, the apogee of overkill, Washington and Moscow sat on a combined arsenal of 64,000 warheads with a yield approaching 20,000 megatons, or half a Hiroshima for every girl and boy born in the United States that year.

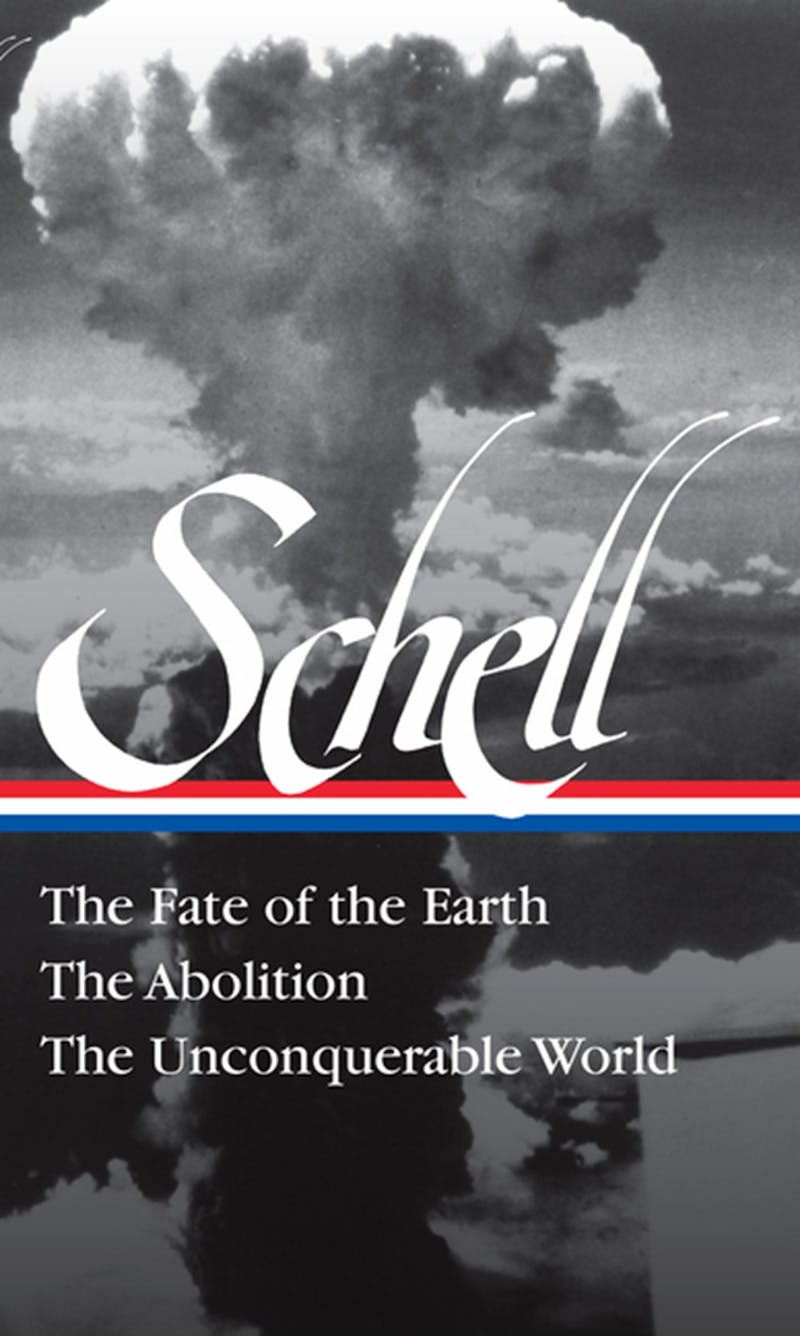

It was during the disorienting final sprint of this arms race that Jonathan Schell produced two of the only enduring books ever written about nuclear weapons. A new edition from the Library of America testifies to their status as classics in a genre full of out-of-print artifacts from long-forgotten and acronym-laden moments in Cold War time—the birth of the triad, the ABM Treaty, SALT II. As a mid-career staffer at The New Yorker, Schell wrote The Fate of the Earth and The Abolition in 1981 and 1983, when talk of imminent nuclear war was less the domain of street-corner prophets than of a Strangelovean cast of senior Reagan administration officials. Rejecting the deterrence paradigm of Mutually Assured Destruction that undergirded decades of nuclear stability, the first Reagan administration pursued policies consistent with Vice President George H.W. Bush’s claim that nuclear war was “winnable.” This shocking disconnect from reality was most evident in the administration’s fantasies of nuclear defense, from space lasers to the dig-a-hole civil defense program advocated by T.K. Jones, Reagan’s undersecretary for Research and Engineering, Strategic and Theater Nuclear Forces, who in 1981 told the journalist Robert Scheer, “If there are enough shovels to go around, everyone’s going to make it.”

Most of the protest literature written during this period can be placed, understandably, somewhere on a spectrum between panic and extreme panic. This includes works by Schell’s British analogue and closest competitor, the social historian and peace activist E.P. Thompson, whose books and essays of antinuclear protest are long out of print. The Fate of the Earth and The Abolition alone have lasted. With few mentions of Pershing II deployments or Helmut Schmidt to distract modern readers, they focus on the permanent underlying condition that Schell called the “nuclear predicament.” This predicament is less about the weapons themselves, let alone specific missile programs and their strategic configurations, than about the meaning of our “second fall from grace,” the bite of the atomic apple revealing the secrets of matter and energy, followed by the Trinity test, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and soon the “fantastic, horrifying, brutal, and absurd fact that humans had wired the planet for its and our destruction.”

Nearly three-quarters of a century later, this wiring remains in place, spreading and fraying in ways that give Schell’s writing a startling and unwelcome currency across the decades.

Because the bomb can no more be protested and conclusively “banned” than the combustion engine, Schell began from a place well outside the traditional parameters of arms control debates and Cold War politics generally. The knowledge of how to build nuclear weapons was transformative and permanent, and it determined the options available to humanity. Only one of these options—a new ordering of human affairs, driven by the rise of a new kind of politics—was compatible with survival. Schell did not just state this but built a case for it around the evidence with lawyerly meticulousness, circling the nuclear predicament with slowly tightening orbits of logic.

The Fate of the Earth begins with unflinching descriptions of what nuclear war would do to New York City, the country, the planet. Schell’s book, drawing on studies produced during the late 1970s by an increasingly alarmed scientific community, became the period’s definitive popular treatment of the physics and faces of thermonuclear death: The first shot of gamma radiation; the electromagnetic pulse; the thermal pulse that lights everything afire within dozens of miles; the blast wave that blows everything still standing to its constituent atoms; and finally, the three waves of radioactive fallout that rain from the dark brown sky of a nuclear winter lasting months and possibly years.

Though this was “hateful to dwell on,” Schell believed such exercises were the first steps to thinking clearly about the nuclear predicament. But stopping there was as likely to lead to apathy and denial as to action. It was necessary to push on. Describing a postwar United States reduced to a bone-strewn “republic of insects and grass” was Schell’s disquieting setup for the book’s long middle essay, “The Second Death,” an inquisition into the meaning of extinction.

The nuclear predicament does not threaten us all with death, he proposed, but with “the death of death.” It has in its sights the future and the past, all of humanity unborn and the memory of everything that ever was. “In weighing the fate of the earth, we stand before a mystery,” writes Schell. Nuclear weapons threaten “not just our lives, but the meaning of our lives.” Although “lots of things could kill us, none of those possible causes reach as deep down into our lives while we are here.” The longer we allow ourselves to live under the nuclear shadow the more we are drained of the strength and imagination required to remove it. “The society that has accepted the threat of its utter destruction soon finds it hard to react to lesser ills,” he writes, “for a society cannot be at the same time asleep and awake, insane and sane, against life and for life.” Enervated by the static background horror of the nuclear threat, we slowly become “allies of death” and “sink into stupefaction, as though we were gradually weaning ourselves from life in preparation for the end.”

Most of the people who have thought much about it have reached the same conclusion: The nuclear predicament, properly understood in all of its gruesome potential, soul-sucking paradoxes, and historical dead ends, can only resolve itself in two ways. We will build a new global political order, or there will be a nuclear war. But whereas others kicked this can down the road in the name of “realism,” Schell sketched out a path toward the short-term abolition of nuclear weapons, followed by the eventual abolition of national sovereignty. His blueprint encompasses deterrence theory, close studies of modern war, political revolution, nonviolence, and moral philosophy. The resulting program is daunting—“The task nothing less than to reinvent the world”—but it is no less realistic than the belief that the status quo is tenable. It also represents a return to the conventional thinking of the early Cold War, one that has in recent years been embraced by well-known peacenik-dreamers such as Henry Kissinger, George Schultz, William Perry, and Sam Nunn.

The first order of business is getting onto solid ground. The “nuclear brink” was too sunny a metaphor for Schell, who saw humanity hanging directly over the abyss, gripping a branch overhead with one hand. Moving to “the brink” required cutting nuclear arsenals from their launch-on-warning hair-triggers (where they remain today) and then separating warheads from their delivery systems. Then could we begin to inch back from the edge, extending the lead time for nuclear holocaust from minutes to weeks and months. The brink will always be in view.

Schell’s proposal of nuclear-weaponless deterrence accepts that states will always possess nuclear knowledge and will thus always live in its shadow, to one degree or another. His ingenious contribution was to suggest the ratification of the stalemate—without the threat of planetary holocaust. Doing so would be like an end-game scenario in chess, “when skilled players reach a certain point in the play they are able to see that, no matter what further moves are made, the outcome is determined, and they end the game without going through the motions.” The arms race could then be seen as a “gigantic educational device.”

By establishing a deterrence system based on theoretical nuclear capabilities and conventional weapons, Schell believed abolition could be temporarily de-linked from the more distant goal of establishing world government. Nations would retain sovereignty and have a shared interest in maintaining an international inspection system to deter and punish nuclear cheaters. Missile defenses could be developed without risk of upsetting a delicate nuclear balance, eventually adding another layer of safety to the system.

This “way station” would give humanity a place to regroup and recharge before tackling the age-old conundrums of sovereignty, anarchy, and war—the unavoidable political issues at the core of the nuclear predicament. Schell didn’t invent this idea so much as dust it off. After early attempts to bring atomic technology under international control failed in the first years of the Cold War, midcentury strategists took it as obvious that a system of sovereign nations engaged in an increasingly complicated balance of terror would eventually have to give way to a new world order. Two of the most influential early American nuclear theorists, Bernard Brodie and Herman Kahn, saw deterrence as a stopgap that would allow humanity to muddle through until Newtonian politics caught up with Einsteinian physics. Yet as the years passed, deterrence theory hardened into the only imaginable or “serious” way of ordering a nuclear world. The eloquent warnings of Albert Einstein were pushed to the sidelines, and the arms race began its exponential ascent.

How we get from Reagan’s destabilizing Star Wars program to the global confederation of Star Trek was the subject of The Abolition and The Unconquerable World, Schell’s opus and last major work, published in 2003. Only in the latter, a treatise of nonviolence and people power, does the role of domestic politics, which was often underdeveloped in Schell, come to the fore. “Peace, social justice, and defense of the environment are a cooperative triad to pit against the coercive, imperial triad of war, economic exploitation, and environmental degradation,” he writes in The Unconquerable World.

This was as close as Schell got to modern movement mechanics. It feels cursory because Schell hewed to a conception of politics colored as much by Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot as any Marxist tract on war and peace. Though there was never any question which side he was on, his instincts led him to look inward, backward, and skyward more than to his immediate left and right. “Such imponderables as the sum of human life, the integrity of the terrestrial creation, and the meaning of time, of history, and of the development of life on earth, which were once left to contemplation and spiritual understanding, are now at stake in the political realm and demand a political response from every person,” he writes in Fate of the Earth. “As political actors, we must, like the contemplatives before us, delve to the bottom of the world, and, Atlas-like, we must take the world on our shoulders.”

Partly reflecting the pressures of being a mainstream writer during the Cold War, he stayed largely clear of the economics of arms racing, and in his great nuclear books of the period he demonstrates extreme restraint in avoiding the story of how Reagan’s nuclear buildup was based on a politically motivated neoconservative “alternative” intelligence assessment of Soviet intentions and power, designed to undermine détente. He justified such omissions—including the chicken-and-egg riddle of the relationship between “peace and hunger”—by citing the urgency of getting back onto solid ground.

In any case, he did not think traditional forms of left organizing and argument sufficient to lead humanity to the Promised Land on the far side of the nuclear predicament. He imagined the journey requiring something both more and less than a “movement” as commonly understood. The antinuclear activity of the early 1980s, he wrote, emerged from “a pre-political stocktaking.” It was “a psychological and spiritual process” that would unfold, as far as he could see, only at the edges of the political arena. In looking ahead to a mass mobilization against nuclear war, he awaited “one of the great changes of heart in mankind—such as the awakening to the evil of slavery—that alter the psychological and spiritual map of the world.”

This awakening proved short-lived and petered out with the end of the Cold War, which did not remove the hair-trigger nuclear threat, let alone deliver a deeper reckoning with the nuclear predicament. In its place arose what Schell derides as the “getting and spending” of the neoliberal ’90s. This great forgetting was possible due to the strange character of the nuclear peril, which Schell compared to a “kindhearted executioner” that allows us to live normally, in a bliss of willful ignorance, until the final day, the final minutes even, before execution.

In January 2020, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock to 100 seconds before midnight, the closest it’s been since the clock was built in 1947. The relative stability that defined most of the Cold War has given way to growing strategic chaos, with few signs of the mass, trans-Atlantic awakening of the early and mid-1980s. The U.S. is two decades into the development of a destabilizing missile defense program, pursuing what looks to Russia and China like first-strike capability. Russia and the U.S. have abandoned the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and are deploying medium-range missiles that shrink an already terrifyingly small nuclear decision window. (Russia’s new hypersonic missile program, a response to the U.S. missile defense program, further compresses that window.) The Trump administration appears ready to allow the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty to lapse, removing the foundation for future arms control and the source of stabilizing information exchanges. Even at current levels of warheads and delivery systems, down to a fraction of their Cold War highs, the biggest nuclear powers still possess planetary overkill capacity many times over. Such is the power of these weapons that even India and Pakistan, though pikers by the standards of the last century’s arms race, could themselves trigger a planetary nuclear winter.

This nuclear threat does not run parallel to the existential threat posed by climate change but is on course to intersect with it. Runaway climate change will produce a return to scarcity that could see nations fighting over basic resources this century, including food and water, as breadbaskets dry up and glaciers melt away. Schell understood this, and he died in 2014 while writing a book about climate change. His nuclear books are peppered with early-warning references to a growing ecological crisis that he correctly perceived as related in more ways than one. He believed nuclear war was the ultimate ecological issue and urged the environmental and antinuclear movements to embrace one another and combine forces.

Schell’s work was continued by his friend and protégé, Bill McKibben, who in 2016 delivered the first annual Jonathan Schell Memorial Lecture Series on the Fate of the Earth. In that speech, McKibben described carbon emissions as responsible for the heat equivalent of detonating 400,000 Hiroshima bombs every day in the atmosphere. Such facts, as Schell knew and McKibben noted, have the power to numb. An existential threat, never mind two of them, is not easy to think about, or organize one’s life around. “Like revulsion and protest against nuclear weapons,” Schell wrote, “a denial of their reality may spring—in part, at least—from a love of life, and a love of life may ultimately be all that we have to pit against our doom.” Every so often, as he worked his way through the many layers of his unfathomable subject, Schell conceded a certain sympathy, and even utility, to the impulse to turn away, forget, pretend.