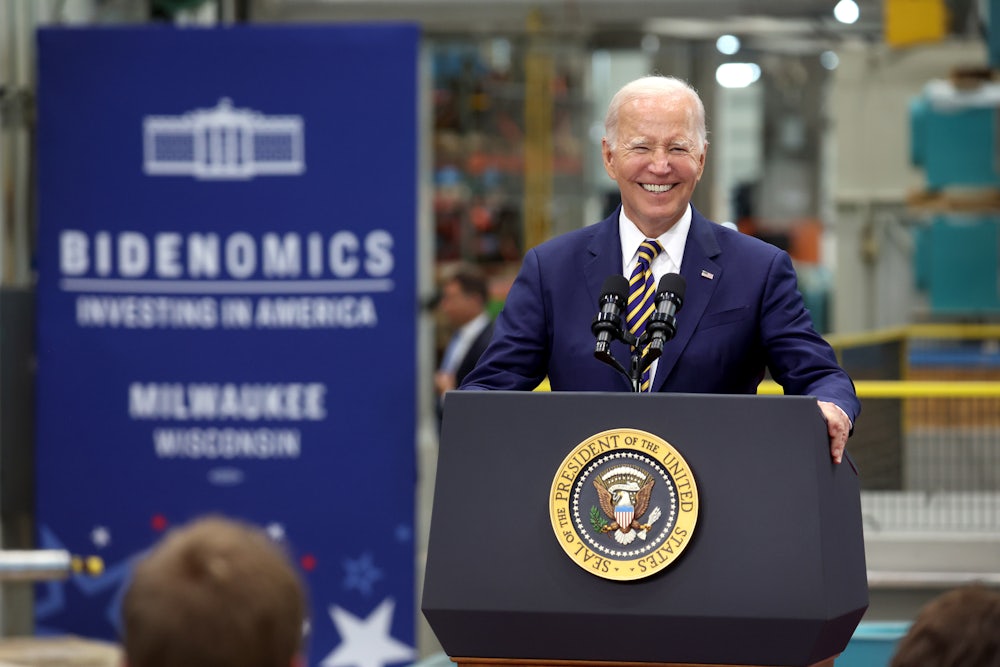

By now you’re well familiar with the right-wing knock on Bidenomics, which is mostly that it created ruinous inflation. That’s pretty obviously wrong. Inflation has fallen by two-thirds over the past year, and French economist Olivier Blanchard, who had predicted the 2021 Covid-19 stimulus would create inflation, coauthored a June paper with Ben Bernanke conceding that it did not. (The supply chain was to blame.) That same month, Republican National Committee Chair Ronna McDaniel attacked Bidenomics by saying, “Savings, real wages, and economic confidence are all down.” Wrong on all counts: Personal savings, real hourly wages, and economic confidence were all up.

The failure of right-wing critiques, which even the congenitally pessimistic business press now concedes, created an opportunity for moderate conservatives to take a whack at Bidenomics. Their spokesman is Robert Zoellick.

“The economic thinkers who generate the intellectual energy for the Biden administration are on a mission: to slay their elders, figuratively speaking, from the Clinton and Obama eras,” Zoellick argued Tuesday in The Washington Post. “The revolutionaries do not just want to devise new policies; they are demanding an ideological transformation to rewire the political mind of the Democratic Party.”

Such umbrage would be easier to take from someone who possessed sincere regard for either president. Bill Clinton, Zoellick wrote in January 2000, “failed to use [his] power wisely or diplomatically.” Barack Obama, Zoellick complained in 2013, was indifferent to “spending discipline” and favored “a bigger role in government and a greater re-distribution in income.” And now Zoellick is recycling these criticism against Biden.

Who is Robert Zoellick? If the idea were still in vogue of an American Establishment, as articulated by the journalist Richard Rovere in 1962, then Zoellick would be recognized as a card-carrying member. In fact, such an establishment continues to exist, but its powers are greatly diminished and its public profile all but eliminated. Rovere named John J. McCloy chairman of his 1962 Establishment. Zoellick, like McCloy a former president of the World Bank, would be a similarly plausible choice.

Zoellick has been U.S. trade representative, a deputy White House chief of staff, a deputy secretary of state, and executive secretary at the Treasury Department, all in Republican administrations; general counsel at Fannie Mae; managing director at Goldman Sachs; director of the Aspen Strategy Group; board member of the Council on Foreign Relations; and national security adviser to Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign (where he was rumored to be in line for secretary of state). After German reunification, Germany awarded Zoellick something called the Knight Commander’s Cross. You get the idea. Zoellick is a Never Trumper, as are most Republicans in Washington not on Trump’s payroll or otherwise dependent on his good graces.

Zoellick has lately positioned himself as the most presentable Republican critic of Bidenomics. In his Post essay, he maps authentically dangerous divisions within the GOP onto the Democratic Party, writing that the latter’s elders who “try to compromise with the upstarts … should be forewarned: Republican leaders waffled in a similar way and lost their contest for ideas.” Oh, please. Democratic divisions certainly exist, but they don’t begin to resemble Republican divisions either in extremity or in posing any threat to democratic governance.

According to Zoellick, adherents to the “new Democratic economics rally around a four-part manifesto.” Let’s take these one at a time.

Ignoring fiscal discipline. In Zoellick’s fevered imagination Democrats have embraced “a wizardry known as modern monetary theory.” For the record, Modern Monetary Theory isn’t wizardry; it’s a carefully reasoned theory that in essence says deficits don’t matter, something Republicans have been saying for decades (though only when a Republican occupies the White House). MMT lacks many followers among Democratic officeholders—even socialist Bernie Sanders won’t say he’s for it—not because it lacks economic sense but because it’s politically naïve. Should inflation rage out of control, the MMT theorists say, Congress will raise taxes. To which the obvious answer is: If Congress were willing to raise taxes we wouldn’t be talking about deficits in the first place. The MMT set seem largely to have gone into hiding during the past year, I presume because nobody wants to listen to them in inflationary times. That leaves Zoellick wrestling with phantoms.

Dismissing the importance of prices and costs. “Biden’s team pursues trade and antitrust policies,” Zoellick writes, “while questioning the importance of prices, costs and efficiencies.” Guilty as charged. I wouldn’t say the Biden administration ignores the impact on prices of trade and antitrust policies, but it’s certainly chipping away at the longstanding orthodoxy that these policies should serve only the American consumer. In antitrust policy, that dictum was laid down by Robert Bork in his hugely influential 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox, a paperback copy of which Amazon, which is about to get sued for antitrust by the Federal Trade Commission, would be glad to sell you for $29.39 (suggesting that even consumers haven’t been especially well-served by four decades of weak antitrust enforcement). Human beings are consumers, certainly, but they are also wage-earners and earth-dwellers, a point that eludes Zoellick as he sneers at the Biden administration’s goals of “helping unions” and “doing away with fossil fuels.”

Celebrating state direction. In a similar essay for The Wall Street Journal in June, Zoellick accused Biden of creating a Washington Ordered Economy, to which he attached the derisive nickname WOE (get it?). In that op-ed, as in the Post one, Zoellick waved as Exhibit A an April speech by National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, whose job doesn’t involve him all that much in economic policymaking, but set that aside. Sullivan’s speech made the uncontroversial point that markets don’t always serve the public interest, and that when they don’t the government must step in. Among the examples he cited were the supply-chain glitches encountered during the Covid epidemic, the erosion of United States competitiveness with China, the climate crisis, and economic inequality. Zoellick sweeps these aside, suggesting that the government has no business directing the economy “beyond infrastructure, R&D and education,” when in fact that government has for at least a century been directing the economy in many other ways under Republican and Democratic presidents alike. Observe, for example, the Transportation Department’s “Automated Vehicles Comprehensive Plan,” issued under that well-known Bolshevik, Elaine Chao. I remember talking about self-driving cars 30 years ago to a political appointee in Bill Clinton’s Transportation Department who was trying to bring them into being. But Zoellick sneers at such efforts, along with such petty considerations as unionization (again!) and childcare. “Pipelines are out,” Zoellick writes. “Solar and wind energy are in.” Fetch my smelling salts!

Slighting international economic leadership. It’s a surprise to me that anybody, much less a Republican, would slight Joe Biden for being insufficiently internationalist. Zoellick is referring mainly to the administration’s weak commitment to creating new international trade deals, which I suppose is a fair knock, except that there’s no support for a new trade deal from either political party while we continue to assess the damage to homegrown industries and large swaths of American geography wrought by previous trade deals. Unmentioned is that the Biden administration has committed the U.S. to a 15 percent global minimum tax, approved by nearly 140 countries, to eliminate mutually destructive competition among nations to attract investment and rid the globe of tax havens. Republicans are doing everything in their power to kill the agreement.

Reading Zoellick’s critique made me nostalgic for the older American Establishment that Rovere wrote about, and the British Establishment that The New Republic’s Henry Fairlie wrote about even earlier, borrowing an ecclesiastical term to describe the United Kingdom’s secular elite in the 1950s. The Establishments of the ’50s and ’60s were highly attentive to corporate interests, but they weren’t confined to them. They recognized other power centers (like labor) and extended their concerns, however imperfectly, to the broader needs of society. Through outlets like the Ford Foundation (where McCloy was chairman seven years) they promoted sometimes liberal, and occasionally even radical policies. Today’s shrunken Establishment, by contrast, is basically a subsidiary of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. It deserves no more of your attention.