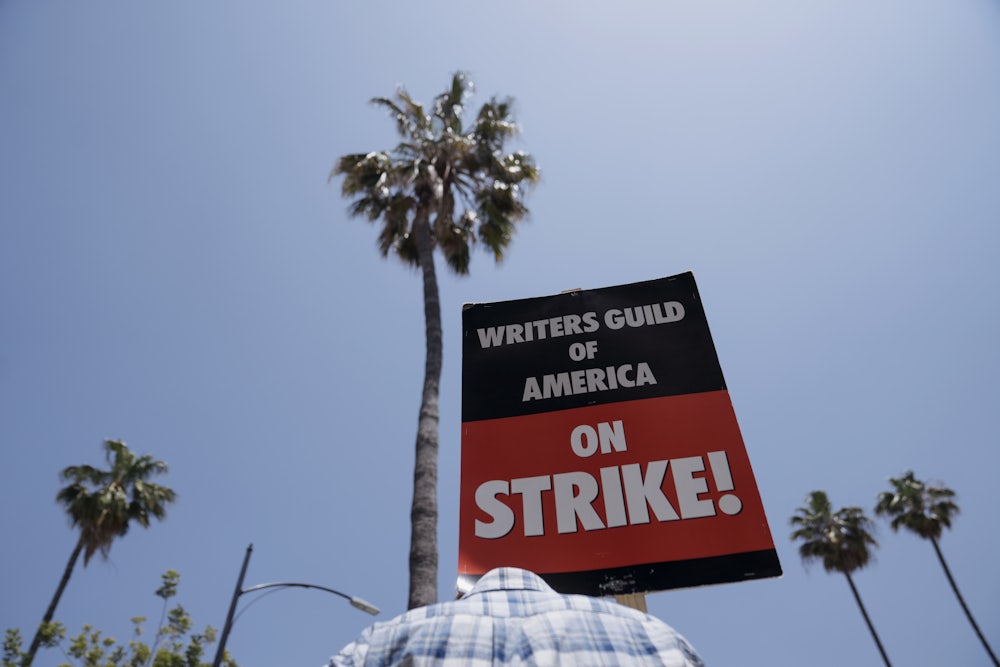

During the last Writers Guild of America strike in 2007, Jesse Plemons killed a guy. Or rather, his character, Landry, on Friday Night Lights, did. Nobody saw it coming. One moment he was a mild-mannered kid living in rural Texas, playing in a Christian speed-metal band and supporting his best friend, the quarterback of the Dillon Panthers. Then, next thing you know, he is bashing some guy’s lights out with a pipe in a parking lot. This turn of events—in the second-season opener—is widely regarded as one of the strangest creative decisions in recent television history.

But that’s not the whole story, of course. If you’ve been following this year’s WGA strike, you’ve likely come across this folk tale—a funny little piece of TV history said to show how the strike brought about a particularly low point in Friday Night Lights. While this baffling event did indeed transpire during what would be a strike-shortened season of television, the episode was written and even aired prior to the declaration of the strike. Lots of things were bad about that sophomore season, and many of them were made worse by the work stoppage. As many people have noted in the past weeks, a “finished” script doesn’t really exist in the television world—scripts are evolving documents, and, especially for a 22-episode serial in 2007, seasons themselves are evolving animals. While the strike did not make Landry kill a guy, it did impede the show’s ability to adapt, to correct for its early-season mistakes, to steady the ship. Instead, the season was cut short, and the show essentially rebooted in its third season, hoping viewers would forget about its past crimes.

So this is a story about a legendary TV plotting fail and a story about the importance of writers, but it’s also a story about recovery and survival. Friday Night Lights recovered, and so too did television itself. Many of the folk legends and tall tales of the last strike that have proliferated online these past weeks have a similar redemptive arc. There’s the legend, for instance, of Conan O’Brien’s on-screen heroism: Rather than hire scabs to replace his writers or come up with new material himself, O’Brien transformed his nightly show into alt-comedy performance art, spinning his wedding ring on his desk, wittily making visible what’s lost when the industry devalues writers. And at the same time, he launched polemics on behalf of his staff in the monologue and personally paid the salaries of all of his affected employees throughout the action—which lasted 100 days. Conan kept his show going, kept his writers on, and they all came out OK on the other end.

Even the false memories are tales of innovation and endurance. A popular myth, for instance, is that the 2007 WGA strike led to a dramatic rise in reality TV. While the component parts of this story track—networks did indeed place an emphasis on unscripted programming during the strike—the broader narrative is misleading. The genre was already incredibly popular before 2007, and, as Emily St. James has pointed out at length, even strike-era success stories like that of Donald Trump’s The Apprentice only have a coincidental relationship to the strike itself. In other words, the WGA strike was responsible for neither the rise of reality TV nor the rise of Donald Trump.

What’s common among these different viral stories is the way they offer grounding in a particularly tumultuous time. While stories of creative disaster like the Landry plotline, of epic gallantry like the O’Brien wedding ring episode, and of villainous origin like Trump’s Apprentice all have vastly different takeaways, they are all stories of continuity, even rebirth. Stories like these can’t explain the current strike, though, nor should they necessarily give us comfort. The TV landscape has expanded in the streaming era, but the place of writers in that landscape, whether we measure it in their pay or in their time, has shrunk. Writers on the picket lines right now are fighting for their very existence against an industry that is in the midst of deciding whether and how they need to exist at all.

One of the central issues of the 2007 strike was the looming emergence of streaming and online delivery of TV and film. The streaming landscape we now know was still years away: Netflix only began its streaming service in 2007 and would not release an original program until House of Cards in 2013. But it was already clear it had the potential to undercut writers’ pay, as previous developments like the emergence of home video had in the past. The WGA’s efforts during the strike ensured that writers would get residuals for the online distribution of their work and ensured that Netflix and other streamers would be required to employ WGA writers when they began producing content exclusively for streaming.

But that mid-2000s reckoning with “new media” pales in comparison with what’s at stake this year. “This strike isn’t just about technological change again,” Christine Becker, associate professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Theater at the University of Notre Dame, told me last week. “This time, as the WGA keeps saying, the stakes are existential. It’s not just that shows are migrating to online platforms, as they started to do in 2007–08. The entire infrastructure of the industry is changing now due to those platforms.” Now the entire future of writing as a profession—what writing even is, and what writers ought to be paid—is up in the air.

Writers make “residuals” when shows they write for are repackaged, resold, or re-aired. On traditional TV, then, a show that enters syndication will guarantee residual payments for a writer as long as the show continues to play. As Eric Thurm points out in his helpful explainer, streaming services have cut around this by offering only fixed residuals that are not tied to viewership numbers, which they are skittish about divulging anyway. What that means is that as the industry has moved toward streaming as its primary model, it’s also moved away from financial security for writers. So, as studios now threaten to experiment with artificial intelligence and fantasize about its ability to replace the work of writers entirely, those writers are rightly concerned about their very existence. Negotiations over these matters have stalled, with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers—the industry’s collective bargaining representative—declining to counter many of the WGA’s proposals.

The stories we tell and the stories we hear about the last strike are not wholly irrelevant to this current labor action, but they also all took place in a media environment that, while tumultuous, was still oriented around traditional structures that don’t even really exist in the same way anymore. The cautionary tale of Friday Night Lights transforms into a story about a writers’ room constrained from fixing the problem they created, but, in the current moment, especially for streaming series, lots of writers’ rooms are dismissed before production starts. Studios have instead begun to use short-contract “mini rooms” that effectively estrange writers—often junior writers—from the production process. That constraint is baked in.

Similarly, we can marvel all we want about Conan virtuosically wasting time on his late night show, but when’s the last time you sat down to watch the entirety of a late-night show live on television and not in viral clips the following morning? Will such activist stunts even be possible during this strike? How can allies of the WGA play with the forms of television when television is so overwhelmingly defined by its dangerous formlessness?

This strike is particularly complex, Becker told me, not only because the issues are knottier this time around, but because “it feels like creative labor is appreciated even less within C-suites and corporate boards than it was in 2007.” Because the major players are no longer just film and TV companies but tech firms and private equity investors, writers face an even steeper uphill climb to convince the AMPTP that their work is valuable at all. Social media is a wild card in this year’s proceedings, with platforms like Twitter giving writers a much greater ability to organize and circulate their message. But, as Becker points out, the ready accessibility of entertainment on apps like TikTok might mean younger viewers simply notice the work stoppage less than they would have in 2007.

The issues at play in this year’s strike—from renegotiated streaming residuals to mandatory staffing to assurances about studios’ use of A.I.—are unique to 2023. In 2007, new media seemed poised to change the way writers did their jobs; in 2023, new media seems poised to render those jobs unrecognizable. We don’t know what the landscape will look like 16 years from now, whether writers will be able to win their security, whether creative work will withstand this epidemic of contempt from the executives who pay for it. And we don’t know what stories will be told of this year’s strike; what heroes and villains will emerge. More than that, we don’t know whether the WGA will be successful, not just in securing its members favorable terms but in restoring writing, as a profession, to a stable place in the industry.

At minimum, writers can learn from the memes of the present and hope they offer some comfort in the future. “Every perceived misstep from every 2007–2008 show is blamed on the strike,” Becker noted, referring to Landry Clarke, Teen Murderer. “Ted Lasso season 3 writers would be advised to start planting those seeds to absolve themselves.”