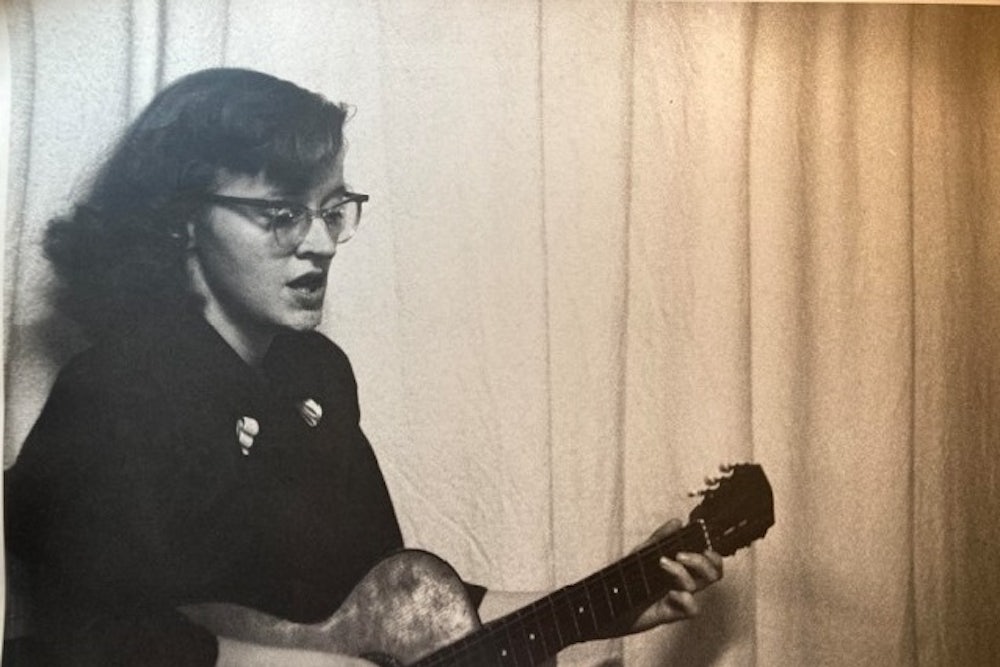

In the 1950s, a young woman in Greenwich Village sat in her tiny kitchen with a guitar and a reel-to-reel recorder to commit to tape the songs she had written. Her voice was wistful and almost pleasantly secretarial—crystalline, plainspoken, a voice seasoned by proper diction. It beveled from grief to a kind of barstool insouciance as it delivered lyrics gauzed with heartbreak: “We go walking out at night / as we wander through the grass / we can hear each other pass / but we’re far apart / far apart in the dark.” This music was the sound of burned-out romance and a lifetime of Sunday nights. Recorded a few years before Bob Dylan detonated a folk explosion in the Village, these songs were also nearly unclassifiable. They were personal but not confessional, symbolic but not hermetic, beguiling but not immediately catchy—at least not in the mold of the pop songs that would soon jangle across airwaves.

The young singer called herself Connie Converse. She had built a modest but devoted following performing at local listening parties. In 1954, she made her national television debut on The Morning Show with Walter Cronkite on CBS. She seemed on the verge of runaway fame. Instead, her career faded before it ever really began. A contract with an agent led nowhere. Record labels deemed her music “lovely but not commercial.” Converse exiled herself to Michigan in 1961—the same year that Dylan arrived in New York to conquer the world—and remained there for the rest of her life. So goes one version of her story, anyway. We’ll never know the ending for certain because, in August 1974, 50-year-old Converse packed up her Volkswagen Beetle and split town, never to be seen or heard from again.

In the early 2000s, Converse’s music resurfaced. An amateur audio engineer who recorded her at his home in 1954 played a track for the WNYC radio show Spinning On Air while being interviewed for an unrelated project. The song caught the ear of a film student, who pursued the cold ashes of Converse’s story over the next several years, which culminated in the magisterial compilation album How Sad, How Lovely, released in 2009. Converse was again a cult darling, and now her disappearance offered an irresistible logline: the female Dylan who wrote a handful of masterpieces and vanished without a trace.

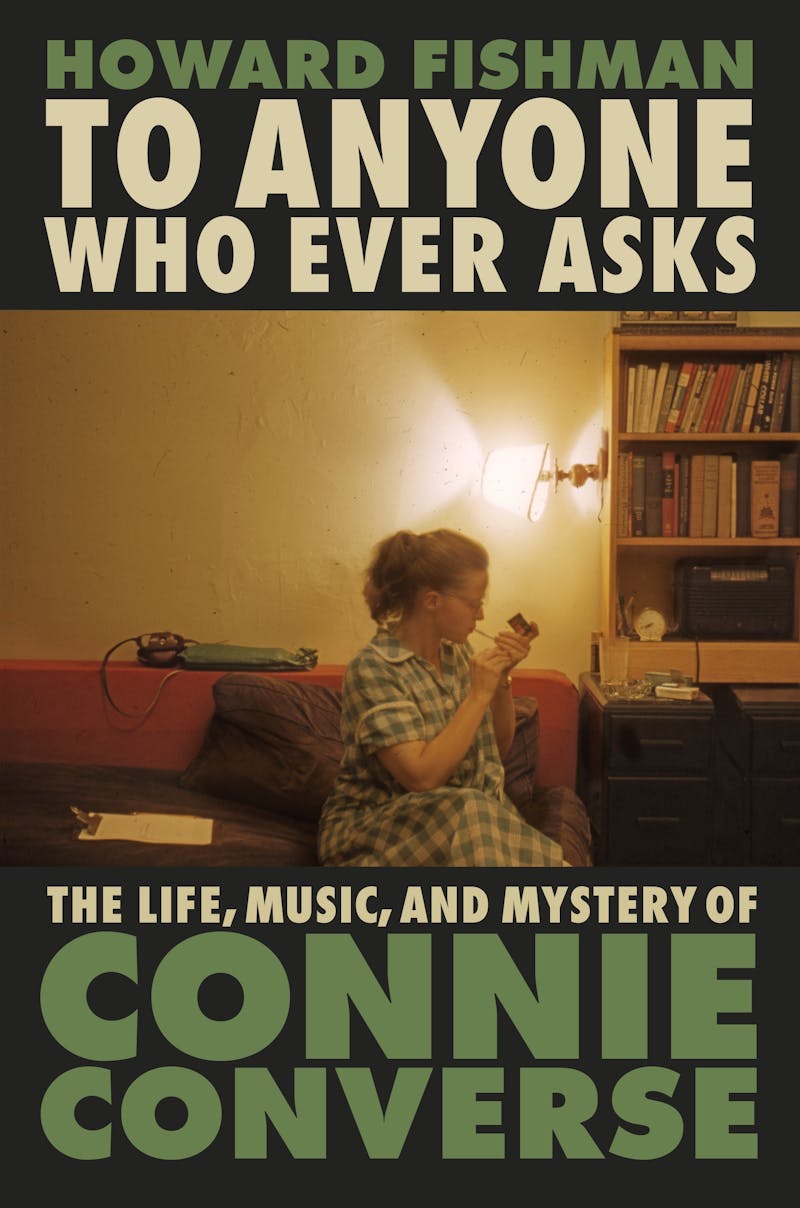

To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse, by the writer and musician Howard Fishman, is the first biography of Converse, although biography is too tidy a word for this shaggy beast of a book. It’s a close study of Converse’s music, a patchwork memoir of Fishman’s own decade-plus obsession with the singer, and a piecemeal reckoning with the Converse family’s history of alcoholism, mental illness, and borderline incest. It’s also unabashedly a fan’s book, with all of the passion and chauvinism that implies.

Fishman first heard Converse’s music at a friend’s holiday party in 2010. The maiden song was “Talkin’ Like You (Two Tall Mountains),” perhaps the closest thing to an earworm Converse ever produced. It begins with a slow, portentous couplet—“In between two tall mountains / there’s a place they call Lonesome”—that then burbles into jaunty ripostes to an absent lover: “Up that tree there’s sort of a squirrel thing / sounds just like we did when we were quarreling / in the yard I keep a pig or two / they drop in for dinner like you used to do.” Here, in two and a half minutes, are the hallmarks of Converse’s style: gymnastic rhymes, sinuous melodies, a tone that’s both lovelorn and self-consoling. As Fishman learned more about Converse, he was convinced she must be a marketing gimmick, the retro concoction of a Brooklyn hipster. “This music, if I were willing to suspend my disbelief, would exist out of time, out of music history altogether,” he writes.

It’s true that Converse seems to float in her own anachronistic bubble. Fishman reaches for parallels to help explain her—the Carter Family, Elizabeth Cotten, Jimmie Rodgers, Molly Drake—without ever landing on the right fit. In a chapter titled “Interlude: Genres,” he argues that one reason Converse never found commercial success in her lifetime was because record executives couldn’t easily pigeonhole her. She was too early to be folk, too early to be a literary singer-songwriter à la Leonard Cohen or Joni Mitchell, and too introspective to be a political or protest singer. (Her lyrics are also often more imagistic than mainstream ’50s fare. “Then my bed is made of stone / a star has burnt my eye / I’m going down to the willow tree and teach her how to cry,” she sings in “Trouble.”) Fishman suggests she was most closely allied with older blues and hillbilly artists such as Riley Puckett, Skip James, and Alberta Hunter, but even those lineages can’t account for Converse’s idiosyncrasies. Perhaps she’s best understood as a precursor to other outliers in the American songbook, such as Cordell Jackson, Daniel Johnston, Hasil Adkins, or Karen Dalton—fellow sui generis musicians who emerged from the roots and funk of their regional culture to create songs of inimitable vigor. “The visionary, forward-looking quality of what Converse had been up to seemed to suggest the need to update the narrative of mid-twentieth-century American song altogether,” Fishman writes.

But who was Converse, and how did she learn to make such singular music? She was born Elizabeth Converse in New Hampshire, in 1924, the middle child in a dour Baptist family that forbade dancing, alcohol, and card playing. Her father was a minister and the head of the local temperance society; her mother was a pianist. The Converses harbored a tainted bloodline that stretched back generations, a fact Connie once mocked in a letter to her sister-in-law: “I trust … that you have been acquainted with the history of our ill-fated family. Great-aunt Flavia was burned as a witch; Cousin Charlie passed away in an Institution; and my brother and I are the last of a long line of bats.” Converse’s older brother, Paul, carried on the tradition of eccentricity. He was closeted and unnaturally curious about sex, according to a cousin, and was known to “mess around” with farm animals. Her younger brother, Phil, the co-protagonist of Fishman’s book, had his own kinks. He confesses that he fantasized about a ménage à trois with his sister and her roommate and that he once gave the girls “a little show” when he was staying over and woke with an erection.

Converse appears to have inherited some of the family quirks. She was prone to depression and, later in life, alcoholism. She was often reclusive to the point of invisibility. Those who knew her remember her foul body odor and the stern, old-fashioned wardrobe that one friend describes as almost “Mennonite [or] Amish” in style. Fishman includes speculation that she may have been a lesbian, or at least had documented relationships with women. She also boasted a near-genius-level IQ of 138 and was the valedictorian of her high school class. Her restless mind, like those of many polymaths, preoccupied itself with various creative ambitions: poetry, fiction, visual art, photography. She won a scholarship to Mount Holyoke College, where, for the first time, her self-destructive impulses roused. In 1944, she abruptly and inexplicably quit school and spent the next several months tramping around the country. Without Converse realizing it, this episode was a rehearsal for later and more tragic desertions.

She moved to New York City and got a job editing a magazine at the American Institute for Pacific Relations, a nongovernmental organization. Rather than quote from Converse’s occasional diary of that period, Fishman instead hazards his own breathless vignette:

It’s easy, and delightful, to imagine her reading The New York Times every morning, following her beloved Yankees, applying her reason and convictions to global problem-solving by day then, staying out as late as she pleased, leaning out her window or perched on her fire escape at night with a lit cigarette while all the creative energy of New York thrummed beneath her—and then jumping back into her apartment to type out some fresh, new inspiration in the wee hours of the morning, trying to give some voice and shape to the overwhelming feeling of limitless possibility that ran through her like an electric charge.

This passage typifies one of the shortcomings of Fishman’s book. In lieu of primary sources, he offers a fan’s sentimental fiction. Barely 10 pages later, he does it again, this time imagining Converse at her favorite neighborhood bar, “a cigarette between her fingers, and a smile on her lips.” Other infelicities are more lethal, as when he cites a contemporary physician’s opinion that Converse may have been neurodivergent.* Despite Fishman’s disclaimer that retrospective diagnoses are impossible, this is still an indulgence no responsible biographer would allow. Elsewhere, he quotes a psychologist who speculates that Converse may have been sexually abused, which apparently explains her off-putting fashion and scant makeup. Throughout the book, Fishman calls upon a range of experts to vouchsafe or elucidate some thread of Converse’s work or personality: a professor at Seton Hall University affirms that Converse’s statistical analysis of song structure was a rudimentary form of “tagging,” as used by streaming platforms such as Spotify; a scholar of Greek tragedy offers her own psychological interpretation of Converse’s song cycle about the mythic Cassandra; and, most puzzling, Robin DiAngelo, the author of White Fragility, is brought in to commend Converse’s racial acuity.

Fishman is on firmer ground when he analyzes Converse’s catalog—more than 60 known songs, or fragments of songs, composed between 1949 and 1969. He writes that “Roving Woman,” from 1952, subverts the harmonic structure of vanilla standards such as “Heart and Soul,” “Blue Moon,” and “I Got Rhythm” to tell a more risqué story of one woman’s rendezvous with the urban demimonde. After a few verses in which a chivalrous gentleman rescues the song’s heroine—perhaps Converse herself—from the disgrace of saloons and poker games, there comes this winking denouement: “Of course there’s bound to be some little aftermath / that makes a pleasant ending for the straight and narrow path / and as I go to sleep I cannot help but think / how glad I am that I was saved from cards and drink.” Whether the “little aftermath” is a goodnight kiss or something more carnal remains ambiguous. Seizing the ironic feminist undertone, Fishman hails the song as Converse’s “Declaration of Independence.”

“Father Neptune,” another song composed around the same time, grafts the opposite theme onto the limber tempo of a sea shanty. Fishman likens the song to the child ballads of ancient English folk music, a treasury of “jealousy, infidelity, murder, death, deception, and fate.” In Converse’s rendition, the narrator is a housebound wife pining for her sailor husband: “He rides through the storm, and the cold and the warm / and he loves to risk his neck / and I like to know when he goes below / that it’s just below the deck.” To illustrate how novel Converse was, Fishman contrasts her song with “You Belong to Me,” Jo Stafford’s pop hit from 1952. It too is a lovelorn woman’s ballad to her seafaring lover, but it’s recorded with orchestral pomp in a diaphanous, slow-burn style that wouldn’t be out of place in an MGM melodrama. To listen to the songs back to back is to hear the difference between a woman staring out a window and a woman pacing the floor.

Converse’s Morning Show appearance in 1954 was a zenith after which came a downslide that lasted until she literally drove off into the sunset 20 years later. She continued to write music, although in the latter half of the ’50s her attention turned to intricate art songs and an opera—a development that many, including her brother Phil, found “artistically alienating.”

In 1961, looking for a fresh start, Converse moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Phil lived. She became managing editor of the Journal of Conflict Resolution, an influential quarterly published by the University of Michigan. “Her office was staid, serious. If you went in there for something, you had the sense you were disturbing something important … the Journal was her life,” a former colleague tells Fishman. Converse’s major achievement in those years was researching and writing a treatise, “The War of All Against All,” a systematic narrative audit of the previous decade of the Journal. In the midst of this painstaking work, her drinking intensified. She burned through three or four packs of cigarettes a day. Her depression darkened.

“Toward the end of 1970 I began to realize that I might have to believe the unbelievable: that the basic nerve and will by which I had always been able to survive may have worn out or broken and may not be readily reparable,” Converse wrote to a colleague. Her final few years were strewn with more dead ends, more false starts. A sabbatical trip to Europe was “a complete disaster,” according to Phil. (“The last time somebody asked me [in Paris] what my future plans were … I broke out in a fit of hysterical laughter,” Converse wrote in a letter home.)

When she returned to the States, she moved into Phil’s attic, then into a nearby hotel, and finally to a predominantly Black neighborhood in Ann Arbor. Shortly after her fiftieth birthday, she penned goodbye letters to her family and some close friends, stating that she intended to start over in New York. But her tone hinted at a more permanent fate. Her letter to her mother ended, “Take care of yourself and get all the enjoyment you can out of life.” While writing the book, Fishman discovered an unsent letter in a filing cabinet in Phil’s garage—the repository of Converse’s archive—headlined TO ANYONE WHO EVER ASKS. This missive is even more frank about what Converse’s plan may have been: “So let me go, please; and please accept my thanks for those happy times that each of you has given me over the years; and please know that I would have preferred to give you more than I ever did or could—I am in everyone’s debt.” Neither Converse nor her car was ever found.

The mystery of Connie Converse is twofold: Where did she go in 1974? And, just as haunting, just as unanswerable, why did her career stall? Fishman chalks up the latter to unimaginative marketing, and if you add to that a tincture of misogyny, bad luck, and poor timing, you likely have the full story.

Beginning in the 1920s, Fishman notes, record companies began to categorize music by genre, a trend that only intensified over the ensuing decades. The result was a domestication of the unruly common language that was American music, and homegrown misfits like Converse were left to rot in the wilderness. It’s a minor miracle that Fishman spent more than a decade chasing down every lead related to her (including a woman who can still recite Converse’s lyrics from memory after hearing them two or three times 60 years ago), and even more miraculous that a major trade publisher took interest in such a project.

Then again, Converse’s story is a natural fit for our cultural moment of reclamation and long-delayed rectification. The book’s jacket copy hails her as an “outsider artist,” a term that, in the visual arts at least, denotes a marketing category with its own galaxy of critics and collectors. That term has murkier currency in the music world, which is perhaps why Fishman invokes a veritable menagerie to help underscore Converse’s rarity. By the final chapters, he even name-checks contemporaneous figures further afield— John Cassavetes, Ken Kesey, David Lynch, Wanda Loden, Alice Neel—as if Converse’s originality can’t even be understood in the context of her peers. As muddled as these comparisons are, Fishman’s point is that the timeline of American music history doesn’t offer a ready-made slot for someone like Converse—a woman who bridged the gap between traditional music and the more expressive and harmonically complex songs that heralded the singer-songwriter boom of the ’60s and beyond.

“This is far from a perfect book,” Fishman concedes at the end—and he’s right. Its structure is too often sloppy, with uneasy transitions from biography to personal digression; its tone is occasionally treacly; its treatment of Converse is hagiographic. But it’s likely the only—the final—full biography of Converse, and so I’m willing to see the book’s clumsiness as endearing rather than disqualifying because I want Converse to finally get her due without reservation. It’s the closest we’re ever likely to come to the cypher behind those beautiful, heartsick songs. As a woman fond of sudden disappearance, Converse seemed to insist on her own evanescence, on her right to stay lost. As she once told her brother, in a coded line of characteristic if accidental poetry: “If I need to go down to the sea, I trust you will let me.”

*This article has been updated to reflect changes made to the book after copies were sent to reviewers.