A novel should be more than just an artifact of imagination; it should be an act of revelation. That’s no less true of workaday genre books than it is of the most deliberately literary works: What distinguishes a good Michael Crichton or John Grisham book from the packs of airport imitators is neither tireless invention nor technical mastery of scene and plot nor the skillful sketching of character but a sense that even amid the trappings of fictional convention, they are showing us something about the world, grasping toward some kind of unique and uncomfortable truth beyond what we can find just by reading the papers and watching the news.

This is why so many novels by politicians, government officials, and those in their orbit—and there are plenty of them! Newt Gingrich! Jim Webb! Lynne Cheney! The Clintons!—are so frequently disappointing. Even at their wackiest—Gingrich’s alternate histories; Cheney’s ribald semi-disavowed Western romance—they stop short of saying much. They perform the tricks, but they never pull back the curtain.

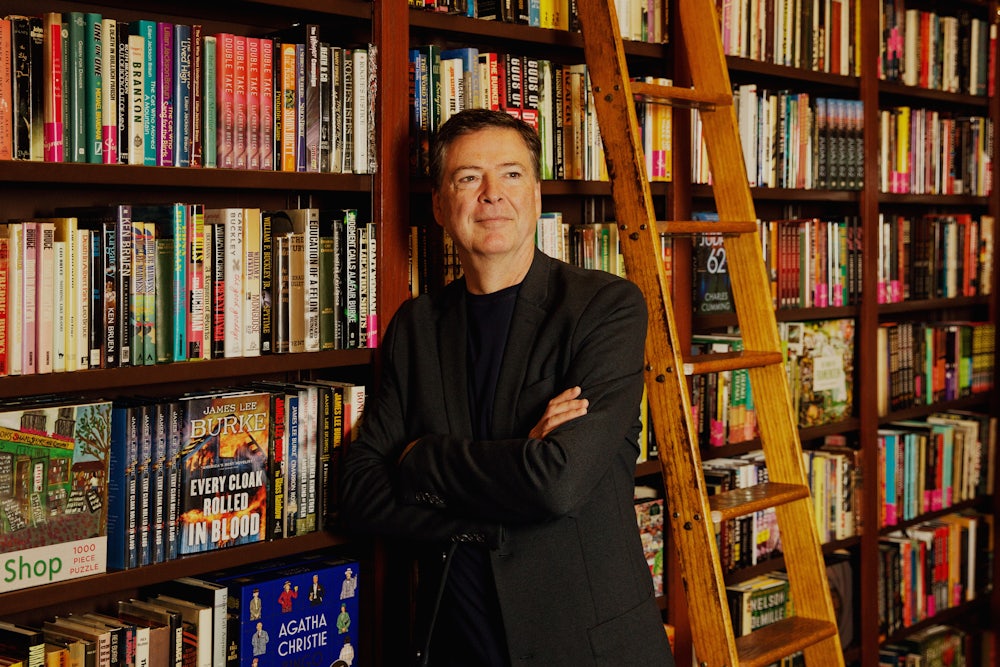

James Comey would seem an ideal person to buck this habit. Now mostly remembered for his miserable stint as the director of the FBI—stumbling gracelessly into the buzz saw of the Clinton email scandal before raising the alarm about Russian election interference, and getting unceremoniously canned by Donald Trump—Comey is a surprising Zelig of the last quarter-century of American politics. He arrived at the Bureau at the tail end of the investigation into Bill Clinton’s pardon of Marc Rich. He put Martha Stewart in jail! He was involved in the Valerie Plame affair, and he was at John Ashcroft’s bedside when the Bush administration tried to strong-arm its drugged-up, postsurgery attorney general into signing off on the National Security Agency’s program of warrantless domestic wiretapping.

His life since he left the FBI has followed a pattern typical for ex-government officials of a certain caliber. He has given speeches, gotten himself a non-tenured appointment at a law school, and sold hundreds of thousands of copies of a score-settling but not unamusing memoir called A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership, which later became The Comey Rule, a bland Showtime miniseries that was nonetheless notable for the great Irish actor Brendan Gleeson’s marvelous turn as Donald Trump. Comey wrote a subsequent memoir with a self-similar title, Saving Justice: Truth, Transparency, and Trust, which was less entertaining and sold fewer copies. And now, like a fair number of former politicos, he has turned his hand to fiction, writing what I can only describe as an OK episode of Law & Order or an unaired episode of The Good Wife: a legal thriller—though generally less thrilling than procedural—of murder, the Mafia, and mistaken identity.

The most intriguing thing about Central Park West—in a way, the real mystery here—is the strange sense that there is something missing. For all his power and access, all those decades of crimes and secrets, Comey has produced any other middle-aged lawyer’s clunky but passable fling at that courtroom novel he always threatened to write. It raises an almost depressing question: Does Comey—do any of these politicos turned authors—have anything to reveal at all?

Central Park West opens, as any airport book should, with a murder, in this case, the murder of Antonio “Tony” Burke, the former governor of New York, in his own apartment by a woman who very much resembles Kyra Burke, his estranged-but-not-yet-divorced second wife. Tony Burke, a corrupt lothario who is mostly Mario Cuomo with a soupçon of Anthony Weiner and a dash of both Bill Clinton and Donald Trump is, in classic TV cop-and-court-show style, a victim who probably had it coming.

Among the other necessary elements, there is a still-present first wife who has her own politically ambitious son by our vic. There are questions about the will. There are questions about a prenup. There is Kyra’s defense attorney, a former federal law enforcement officer of some kind, now working at a white-shoe firm, who believes his client is truly innocent, goddammit. There is the vic’s former top aide, Conor McCarthy, now firmly in Kyra’s corner, though not without some secrets of his own. There is a media circus around “Killer Kyra,” harrumphing idiosyncratic judges, and, across town, a crusading U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Nora Carleton, and crack organized-crime investigator Benny Dugan—of course an alcoholic and of course estranged from his own adult children—whose sprawling prosecution of Mafia capo Dominic “The Nose” D’Amico and subsequent investigation into The Nose’s own assassination for an offer of cooperation will turn out—the reader will be shocked to discover—to be inextricably intertwined with Burke’s death and Kyra’s own case.

Along the way, we will meet a female Mafia assassin, a semi-corrupt U.S. attorney who, of course, is more interested in cameras and publicity and wants to shut down Nora and Benny and their damn investigation into this Burke mess, which has nothing to do with their case, goddammit. We will be treated to a surprisingly sensitive treatment of Nora’s financial and personal struggles as a mostly single mother and then her tentative lesbian coming-out. There will be a running gag about that same shithead U.S. attorney appropriating an attractive office rug from his put-upon secretary, Georgene, a detail of such bizarre specificity that I must believe it reflects a real episode from Comey’s own earlier career. There will be, as in any pretty decent episode of Law and Order, a Big Twist, a Surprise Reveal, and then another twist.

To describe the prose as workmanlike would be too kind. It is often lurching and awkward, and the dialogue frequently reads like someone ran the original English through a machine translator into a foreign language and back again, particularly when it is indulging in tough-guy cop and Mafia talk. Location descriptions are painful, like notes that a more fluent writer would plug in fully intending to come back to on a second draft. (One single paragraph describes two Centre Street court buildings as “a Greek-temple-looking courthouse” and “that Soviet-looking building.”) Moments that should deliver a quick plot point drag on, while courtroom scenes—where Comey is clearly at home—are oddly truncated.

But there is still something to like here. Within reason.

For all its clichés, it is a work of genuine imagination. It is plotted with

reasonable care, and while its final reveal stretches the boundaries of

credulity, it is not nearly as ridiculous as, for example, the

post-career co-written thrillers of Bill (with James Patterson) and Hillary

(with Louise Penny) Clinton. Nor is it as self-serving. Like any amateur

novelist, Comey has too liberally and too obviously sprinkled the work with

episodes from his own life (the rug being only the most egregious and silly

example), but other than a habit of precisely describing his protagonist’s

heights (Comey is famously six feet eight inches; his heroes are pretty much

all over six feet), he has resisted the urge to make himself a character in his

own book. Bill Clinton’s The President Is Missing and follow-up, The

President’s Daughter, are both transparent fantasies about versions of Bill

Clinton; Hillary Rodham Clinton’s State of Terror is about a … recognizable woman secretary of state. Comey has at least gone to the trouble

of imagining characters who are not matinee fantasies of himself. Credit where

due. A stronger editorial hand, a couple of years in TV writers’ rooms, or

perhaps a few years in a low-residency MFA, and I suspect that this James Comey

fellow could really get the hang of this novelist thing.

And yet, I am also plagued by a kind of disappointment, which I felt as well when paging back through those Clinton novels or recalling Newt Gingrich’s mid-2010s Brooke Grant trilogy (completely absurd but, I am forced to admit, perfectly serviceable), Duplicity, Treason, and Vengeance. A sinking feeling: Is this all?

Because we do live in a golden age of conspiracy, an age of stories, and it is a bit disappointing to get from a former top G-man little more than the interagency rivalries that 75 years of TV cops, courts, Feds, and spooks have already burned into our brains. The most powerful people in the real world jet off to private sex islands. Justices of the Supreme Court hobnob at the Bohemian Grove with weird billionaires who collect Nazi memorabilia the way others accumulate rare stamps or unopened Star Wars action figures. The Deep State. Pizzagate. QAnon. Discord leaks. Reality Winner. Chinese spy balloons. Drones. A.I. Robot police dogs. A pervasive sense that beyond the veil lies another veil, and beyond that, a realm of decadent secret perversion and lies, a stygian realm of occult amorality, vast unaccountable agencies of secrets and death and war directing the vast energies of history toward some Luciferian end, while we poor proles labor under the illusions of free will, of self-determination, of democracy, or agency.

How deflating, then, to discover that the most these semiretired potentates of the great secret machinery of government can imagine amounts to a rip-off of more professionally written TV shows and mid-tier Hollywood action properties! How sorry it is to discover that after eight years as president, or after being the most powerful man in Congress, or years as secretary of state or director of the FBI, the tales they produce—the fantasies of those who actually held such power, who knew all the secrets—are the same fantasies as any schlub watching Air Force One while he irons shirts in an airport Sheraton on his way to a sales conference. It is as if Dan Brown rushed his wild investigators into the heart of the Vatican to discover only that the pope eats Cheerios for breakfast and enjoys reruns of Friends.

Of course, it might all be a feint: the dullness, the limited stories, the banality. It could all be a form of camouflage, to render the romanced dream lives of our rulers so utterly quotidian that we cease to wonder about the actual reality that must lie beneath. But somehow I don’t think so. They are all as depressingly ordinary as they appear; they have the same pop-culture-saturated ideas about terrorism, the Mafia, the cops, the spies, the operators, as the rest of us, chatbots endlessly recombining the same familiar stories in slightly different order. “He was one of us,” the poet Robert Lowell said of Mussolini, “Only, pure prose, and less miraculous.” Isn’t that sad? That at the end of the day, none of our great and powerful have much to reveal, and they are all exactly, depressingly, precisely what they appear to be.