Great art penetrates, for better or worse. It gets “inside” and lingers there; it excites emotions, makes you feel elated, vulnerable, mortal. If great art penetrates, does aesthetic experience entail feeling a little penetrated by the artist himself (it usually has been him)—does something of his being or soul infiltrate yours, breaching the usual human boundaries? Isn’t that the whole frisson of the thing?

Aesthetic pleasure isn’t unrelated to religion, both being in the transcendence business, meaning that sometimes artists have been mistaken for or moved through the world like gods. People worship them, want to sidle up to, bed, or marry them. Artists often being men, many of those doing the worshipping are women. Bad things follow, because artists are also, not infrequently, smug pigs or insecure creeps who suck up all the adulation on offer in a futile attempt to repair the cavernous emotional wounds that made them into artists in the first place. Or such has been the modern conception.

From the earliest days of an art market and attendant conceptions of individual genius, the eccentricities and bad behavior of the artist have factored into the mystique of art and its value. Artists were granted tacit exemptions from the usual social proprieties, celebrated rather than penalized for their transgressions. Biographies began being written about them—Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in 1550, though not especially factual, propelled the new genre, which only enhanced their standing and charisma.

But penetrated boundaries feel dangerous to the more fragilely constituted selves we’ve become. The behavior exemptions are being clawed back, charisma has started to seem sleazy, and “genius” smacks of elitism. Vasari’s clout has grown bigger than he could have envisioned, to the point that intel about an artist’s behavior now supplants aesthetic judgment altogether (still regardless of factuality).

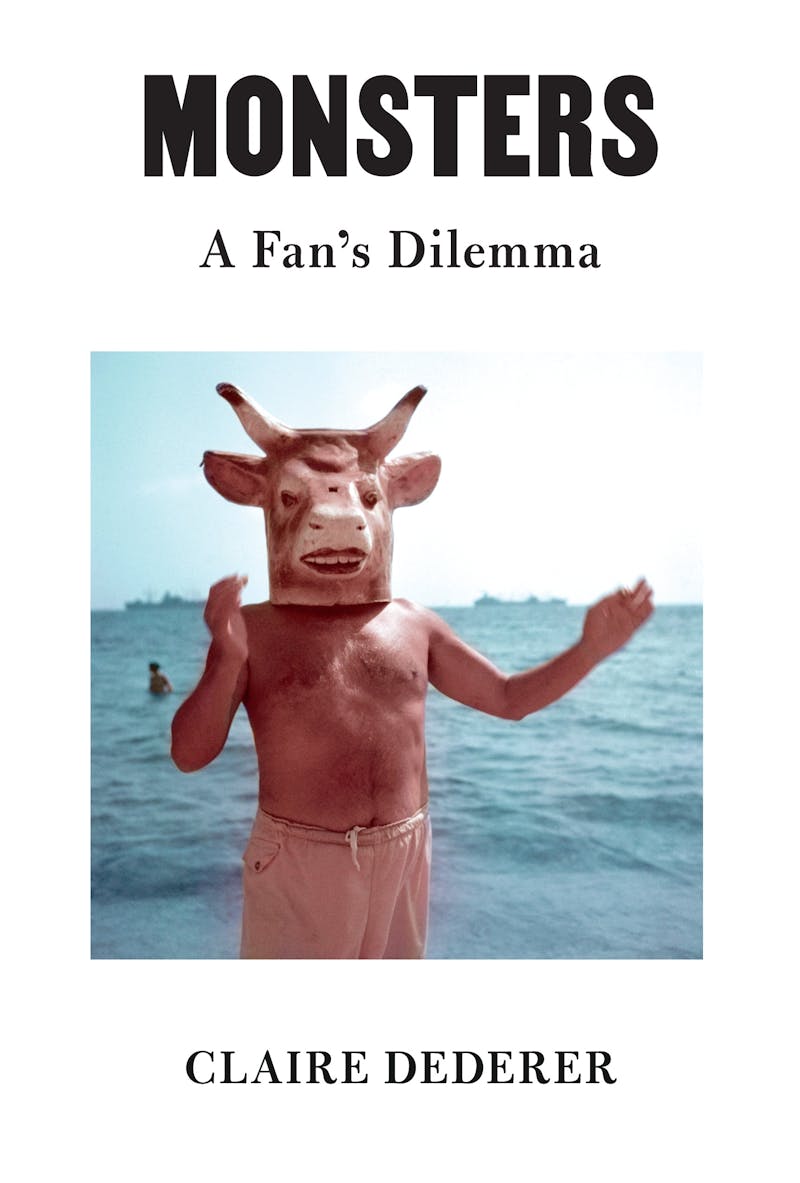

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma embraces the new biographical supremacism, though it leaves her with a set of quandaries. Particularly when it comes to the cultural personages Dederer labels “monsters,” a term that has multiple meanings here. There are “art monsters,” a term she borrows from Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, meaning those enviable figures, almost never women, who have put their art careers over everything else; then there are artists “whose behavior disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms,” which can’t be disentangled from some “dark aspect of his or her biography.” It’s these last monsters who won’t leave her alone.

Can she still love the music of Miles Davis knowing that he beat up multiple women, or admire Roman Polanski’s films when he’s confessed to drugging and raping a 13-year-old? Continue to bop to Michael Jackson, who was accused of molesting children? What about her reverence for David Bowie, who slept with a virginal 15-year-old who’s said she has no regrets, but which leaves Dederer feeling “horrified and sad.” This is what it means to be a cultural consumer at this point in history, she believes: Capitalism has given the audience a new job, which is to act as though our preferences and desires in art are moral questions and to think our consumption patterns define us. Maybe they don’t, but Dederer seizes the role anyway, yearning for an online calculator to weigh the heinousness of the crimes versus the greatness of the art and tell her whether she should or shouldn’t consume the culture in question.

The pragmatist in me suspects the answer to these conundrums is simply acknowledging human complexity: Caravaggio was a murderer; bad humans can be great artists. Dederer thinks it’s impossible to make that separation anymore: We don’t choose to be moral vigilantes; the role is foisted on us. Rather, it’s foisted on women, along with morally aggrieved (because perpetually online) young people. Meanwhile, men, especially over-cerebral male critics, she argues, exempt themselves by tossing around condescending terms like “biographical fallacy,” which Dederer treats as the male critical establishment’s plot against female intuition and herself personally, though she also treats biography as the equivalent of a police blotter. Monsters is her retort to all the men who have made her feel trivialized over the years for responding emotionally instead of intellectually to movies and art.

Despite a pretty deep dive into some mildewed gender binaries, Dederer wants to avoid being a scoldy feminist cop. Yet her wariness of the preening virtue-mongering of the moment clashes with her wish to honor her moral intuitions, no matter how inconsistent. The outcome is a book frequently divided against itself. One of Dederer’s charming or annoying writerly traits is the habit of acknowledging that an argument is shaky, then making it anyway, like a tactical trial lawyer willing to be overruled on a prejudicial question, since it’s not like the jury can really unhear it. Moral judgments whiz through the air like missiles, followed by sheepish denunciations of moral judgment. She regards the biographical lens as “natural,” while deriding it as a by-product of the online outrage industry. Dederer writes well about the thrill of outrage—the pleasure of having new monsters to denounce, the self-congratulation built into these pastimes, the shame at its core—but it’s a contradictory two-step: critical of rushing to judgment while doing so vigorously.

The majority of the monsters on display are, no surprise, men, with a sprinkling of women for equity. The bad men are mostly abusers of women, the bad women are mostly bad mothers: Just as there’s a gendered division of labor, so is there a gendered division of monstrosity. The depraved-men beat is by now familiar territory—there is, Dederer acknowledges, a vast literature on Picasso’s ratlike behavior to his wives and lovers and Hemingway’s problematic virility, not to mention their mutual silly fascination with bullfighting, which sucked in more credulous generations of fans, and which Dederer dismisses as wanking. Despite her diffidence about feminist smugness, there’s no shortage of reflexive feminist mockery of men, though also a wonderful passage about the special female thrill in locating the tender heart of the brute. It’s certainly true, as she points out, that the conflation of genius and masculinity hadn’t been a beneficial thing for women, though I suspect it comes as a cost to the geniuses, too: Hemingway wasn’t exactly an untormented guy.

Dederer claims not to be making a virtue of the present, but there are certain hard stops on her historical relativism, particularly when it comes to sexual morality. Despite knowing it isn’t timeless, she feels as though it should be. It’s here that the inward gaze becomes most intellectually hampering: Historical perspective doesn’t come from within, and if the monsters that most arouse her ire are the ones who engage in intergenerational sex while ignoring its “moral implications,” this is clearly our moment’s obsession, not that of societies past. Somehow these feel like more dangerous times: Sex and culture have both come to be seen as exponentially more invasive and trauma-causing than a few decades ago. Are we more porous beings than our predecessors or just more into playing auxiliary cops? Dederer’s problem is that watching Woody Allen’s 1979 movie Manhattan, widely acclaimed in its day, makes her feel “a little urpy,” because it depicts a consensual relationship between a 17-year-old high school student, Tracy, played by Mariel Hemingway, and 42-year-old television writer, Isaac, played by Allen, or, in her words, “an old dude nailing a high schooler.”

To say that Dederer is supremely bothered by this relationship would be an understatement, and despite insisting she’s not reading the movie via the lens of Woody’s subsequent relationship with Soon-Yi Previn (his former partner Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter), which started when she was 21, she also treats the two relationships as interchangeable. She can’t get past the idea of Woody “fucking” Soon-Yi, just as in Manhattan Isaac fucked Tracy. In her moral-biographical calculus, the real Soon-Yi was no more capable of sexual consent than the fictional Tracy, because Dederer feels that a 17-year-old is a child, and felt growing up as though Woody belonged to her, and thus took the “fucking of Soon-Yi as a terrible betrayal of me personally.” About the (vigorously contested) allegations that Woody molested his then 7-year-old daughter Dylan, Dederer is agnostic—“We don’t know the real story, and we might never know”—which seems like a sensible position, yet post–Soon-Yi, she explicitly regards him as a predator.

The unstated and unexamined premise is that a young woman can do none of the choosing and none of the fucking, regardless of anything Soon-Yi has said to the contrary. As far as Manhattan, it seems worth noting that sex in the post–sexual revolution decades was generally regarded as a more benign enterprise than it is these days: In 1979, the Isaac-Tracy relationship could be seen by mainstream audiences as something fictional in a movie, not an instruction manual for cradle robbing. But words like “predator” and “grooming” also didn’t trip from the lips back then, or present such clear and present threats—one thing about which QAnon followers and liberal feminists can at least now agree. No doubt the drumbeat of sexual harm has made the world feel slimy and fearsome for a lot of women, but when Dederer accuses Woody of performing “artistic grooming” on his audience, it sounds like he’s running a D.C. pizza parlor as a side gig. When she aligns his remarks about his love for Soon-Yi (“There’s no logic to these things…”) with Donald Trump’s “I moved on her like a bitch,” I longed for a few of those supposedly “male” critical distinctions. I mean … really?

Taking up the Monsters challenge, I rewatched Manhattan to see if it would also make me feel “urpy.” I confess I found it refreshing to shelter briefly in a world where sex was just something people did together, not a trauma in the making. What I’d forgotten about Manhattan’s emotional dilemmas is that, in the universe of the movie, it’s love that’s hazardous, not sex. Tracy and her older counterpart, Mary (who’s involved with a married man), both suffer from insufficiently reciprocated love—it’s feelings that injure us, not fucking, and men are just as romantically confused. I understand the poignancy would be lost if all you see is an old dude nailing a teenager, but then you actually are lording it over a bygone era, while promising not to.

Then there are the women monsters: Doris Lessing, who left two of her children with her ex-husband in Rhodesia and immigrated to London with a third, is stained by the act, even though, as Dederer notes, it’s the kind of thing men do all the time. She ponders whether writing a world-changing book could ever compensate for child abandonment.

Dederer herself is intensely invested in being a good mom, carting her kids to concerts and museums, recording their takes on cultural and moral matters, though her ambivalence about the strangleholds of motherhood is also frank. Could she have been a Nobelist if she, too, had ditched her children? Needless to say, plenty of creative women have managed to dodge these strangleholds, but Dederer feels guilty even leaving her family for a brief artist’s residency, and thinking about the poet Anne Sexton revealing to her shrink that writing was as important as her children makes Dederer want to throw up. Even giving up a child for adoption, as Joni Mitchell did at age 21, categorizes her an abandoning mother here, a parable of both “empowerment” and “selfishness.” When she thinks of Joni, Dederer thinks of her “lost daughter,” wondering whether that disrupts or enhances the music for her. I read this with no little trepidation: What about all of us who have had abortions because kids would get in the way of a creative career—are we parables of selfishness as well? Dederer is obviously too attuned to progressive optics to go there, though when her mother also judges Joni’s behavior selfish (and her music inferior to Carole King’s—Joni’s is pretentious), I saw where the moral stringency might have originated. It was like a case history in a sentence.

Much of the time I spent reading Monsters, I was writhing in discomfort at what I suppose could be called the female condition—and at how many of its strictures seem so self-inflicted. If men are the beneficiaries of a proclivity toward monstrousness, is the female fate to be saddled with way too much compunction? Making great art isn’t sufficient; you have to be a morally exemplary person and even then worry what other women think of your choices. Dederer wants to know if creative freedom invariably comes at someone’s expense—does it require being an asshole, and is this trait distributed or tolerated differently according to gender? “The violence of male artists is tied to their greatness,” she says, but is the requirement to ponder such questions in the first place another of the hidden taxes on womanhood?

Or are these gender binaries themselves further hardened by Dederer’s curation of examples: Obvious male culprits are perp-walked through the pages, while obvious female culprits seem to get shielded. Anne Sexton is discussed, though—oddly, for a book titled Monsters—her daughter’s sexual abuse allegations against her are not; Simone de Beauvoir, who was accused of seducing female students (and in later years, young acolytes) and then passing them on to boyfriend Jean-Paul Sartre (and comparing notes), comes up not at all. To name just a few.

Just as the torrent of indictment was getting me down, Dederer complicates matters by taking up the monster’s point of view. It turns out she’s a monster, too. Well, she had a drinking problem, then stopped drinking. We’re all monsters, she comes to realize, and loving people who do monstrous things is the great problem of being human.

Dederer is at her best on such complicities—her own fondness for assholes, our cultural fascination with monsters—and less convincing when in a dudgeon, or deploying her feelings and experiences as intellectual credentials. When she says that she has special knowledge that qualifies her to pronounce on Woody’s transgressions with Soon-Yi because she herself was raised by her mother and her mother’s boyfriend, and thus she knows what the contours of a stepfather relationship should be, it sounded both flimsy and overinsistent. Is a daughter desiring a mother’s boyfriend, even at some subterranean level—and Soon-Yi did apparently desire Woody, to whom she’s now been married some 25 years—entirely unknown? The places Dederer seems unable to allow her imagination to travel are the places she tends to get the huffiest.

Nowhere is this more the case than in her use of the term “predator,” which gets thrown around exceedingly casually here. Like most women, Dederer has experienced a plethora of major and minor sexual assaults over the years—more special knowledge—which apparently justifies taking a hard line on the perps. This doesn’t have to be the case: Just as liberals who have been mugged can choose not to become neocons, women have political choices to make, too. Dederer sees it differently: When it comes to predators, down comes the hammer, however transient or ambiguous the offense. The hammered include a member of the two-person Seattle queer punk band pwr bttm, who was accused, on the eve of the release of their career-breakthrough second album in 2017, of “initiating unwanted sexual contact with young female fans,” as Dederer puts it. In the space of a week, the album was pulled, their management dropped them, and the tour was canceled. The band soon broke up. Dederer and her daughter, who hail from the Seattle area and had formerly loved the band, meet a young woman in a local café who still loves and listens to them despite everything, which gives Dederer what she calls “a true Joycean epiphany, a sudden realization of the whatness of the thing.”

I wasn’t quite sure what this meant, but I looked up the case, which hinged on a bunch of contested online allegations. A woman whom band member Ben Hopkins—who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns—had hooked up with on multiple occasions the year before (Hopkins says consensually) pseudonymously alleged that she’d been assaulted. Another punk scene habitué, having observed an allegedly unconsented-to kiss in a club by Hopkins directed at the person’s date, then made a mission of publicizing anonymous accusations about Hopkins on Facebook, labeling them “a known sexual predator.” Hopkins’s father, too, was said to have made inappropriate advances to women. An anonymous Twitter account circulated more anonymous complaints. In an interview with Billboard a few years later, Hopkins described themself as having been suicidal in the aftermath.

Those who study online behavior call this “mobbing.” It surprised me that Dederer, who thanks the members of a prison abolition reading group in her acknowledgments, piles onto this mess. Is everything people accuse other people of online true? Nothing ever exaggerated, or in bad faith? Wouldn’t a cultural critic interested in prison abolition want to consider the connection between a society dedicated to mass incarceration and the penal mindset we call “cancel culture?” Watching putatively queer communities devolve into frenzies of accusation—a predator under every bed to be rooted out and ruined—oblivious to the brutalities inflicted on queer generations past by sexual witch hunts past, is depressing. There’s nothing anti-normative or oppositional about this; it’s the youth brigade of neoliberalism.

It’s easy to fulminate about consumer capitalism, less easy to contemplate the extent to which the carceral mentalité of our political-economic moment saturates even our imaginations, dictating the horizons of what freedom or utopia might look like, or what futures we can imagine. Even what critical questions we can ask.

Feminist arts criticism over the last half-century has enumerated the myriad ways—institutional, pictorial, psychosocial—that women and women artists have been relegated to inferior status. But feminism itself comes in progressive and conservative versions: There are plenty of carceral-minded law-and-order feminists, and they’ve had terrific success at reshaping cultural mandates, even dictating what audiences are or aren’t allowed to see. In 2018, the largely federally funded National Gallery of Art canceled an upcoming show by the painter Chuck Close after accusations of sexual harassment surfaced. The price of his work plummeted, and when he died in 2021 his reputation was still in tatters. The literary canon is being similarly reshaped, with any number of previously revered writers—David Foster Wallace, Sherman Alexie, Junot Díaz—scrubbed from the curricula by cultural sheriffs, as if whatever bad things an author is alleged to have done make the work itself a moral hazard. Even in the rare case of a formal institutional process clearing the accused, as with Díaz, no amount of exoneration suffices for the staunch-minded.

This is now our official national culture: Exemplary conduct is required of all (even the dead), deviations will be career-ending. Artists once again serve at the pleasure of officialdom, whose purview—like the surveillance state itself—grows more total by the day.

Do we really want musicians to rein in the eros, filmmakers not to depict anything sexually untoward, allegations to equal guilt? Artists of decades and centuries past to be held to present-day comportment standards? The consensus appears to be yes. What a prissy and punitive world ours has become. I don’t think Dederer entirely applauds it—she concludes that the important thing is for fans to love the art they love—but I could still hear the cell doors clanking in the background.