“People do not give it credence,” Mattie Ross recounts in the marvelous opening paragraphs of Charles Portis’s True Grit, “that a fourteen-year-old girl could leave home and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood but it did not seem so strange then, although I will say it did not happen every day.” It’s a voice that could define almost every Portis protagonist—a self-taught, partly untamed individual of weather-roughened accomplishments striving to articulate the story of their life while battering along the roads that carry them (briefly) away from home and (inevitably) back home again.

After the “coward” Tom Chaney senselessly murders Mattie’s generous father and absconds with his wallet and two gold pieces, she determines to bring him back to face trial, and recover both gold pieces while she’s at it. To that end, she enlists Rooster Cogburn, former bank robber-turned-deputy marshal, a “one-eyed jasper that was built along the lines of Grover Cleveland,” first encountering him outside the courthouse where Cogburn has been testifying to his latest murders in the name of the law. As the prosecutor points out, Cogburn is responsible for “twenty-three dead men in four years. That comes to about six men a year.” To which Cogburn replies: “It is dangerous work.”

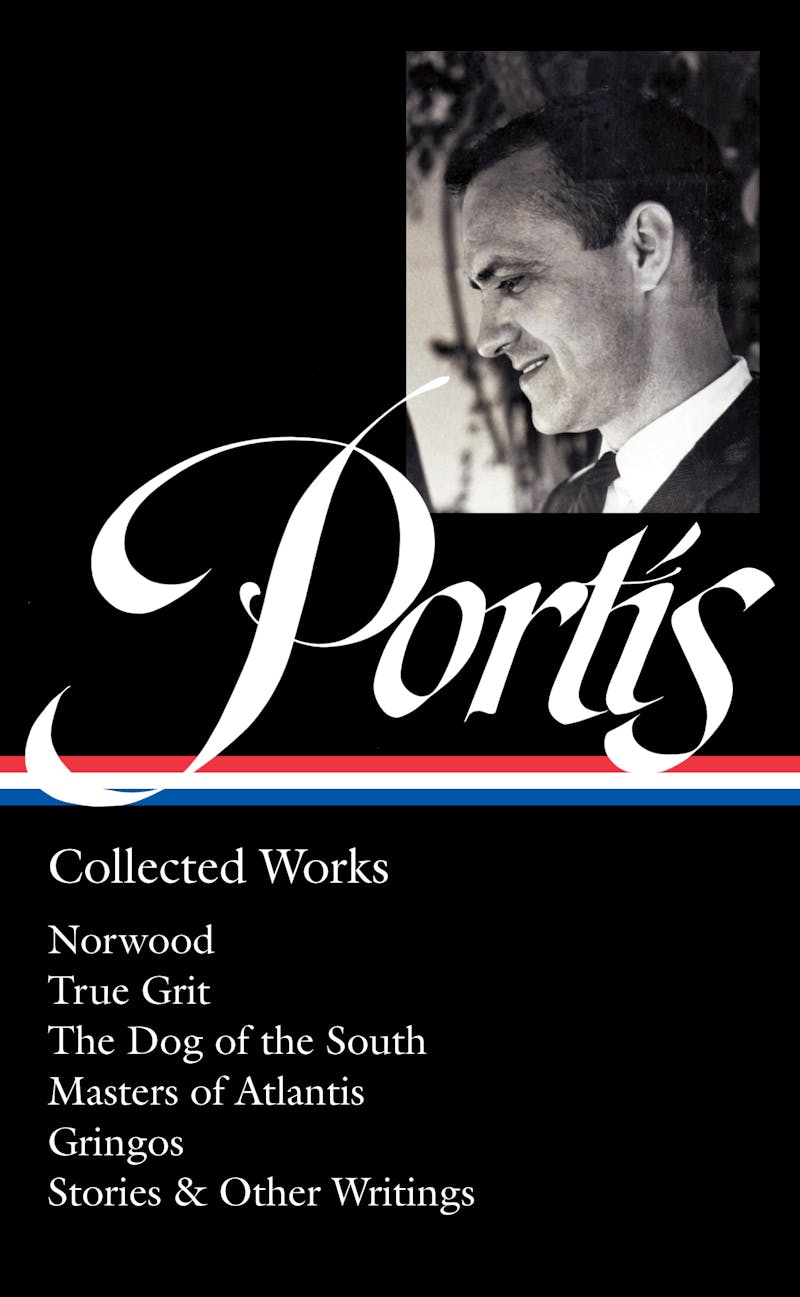

True Grit is a wild ride for readers, and the brisk, bright scenes of dialogue seemed effortlessly translated into two successful films—one in 1969 starring John Wayne and directed by Henry Hathaway, and a second in 2010 by the Coen Brothers. Both contributed to the image of Portis as a bard of the Old West, a sort of hybrid of Louis L’Amour and Mark Twain who staged wide-angle gunfights between near-mythic cowboys and dastardly villains. When he died, at 86 in 2020, major obits remembered the author of a “Western classic,” while summarily noting his debut, Norwood (also filmed), and his three subsequent, unfilmed novels. But True Grit, written in 1968 when Portis was 35, was a deeply uncustomary novel for Portis, who had never taken the tall tales of his Southern youth quite so seriously before, and never would again.

Over a quarter-century, from Norwood in 1966 to 1991’s Gringos, Portis wrote a handful of shortish, densely hilarious novels that explored the deep peculiarity of middle-American life. His characters are self-absorbed, lazy, lonely, unkempt, self-indulgent, and so deeply complacent that they rarely seek anything outside the boundary of the lives they already know. They spend their days reading and drinking with a sort of happy indolence—there’s the expatriate Jimmy Burns in Gringos who has dropped out of regular employment to dig up artifacts in the Mexican jungle, or Lamar Jimmerson in Masters of Atlantis, who cares more about promoting universal truths than about the world’s wars and general mayhem. They are difficult for their women to live with. And so their women often leave them.

Yet while these later novels were often his most comically unusual and inventive, they failed to sell very well, and, though widely reviewed, they often suffered unfavorable comparisons to the earlier work. None achieved the cinematic clarity of True Grit; they don’t translate into other media, and can’t be explained in terms of familiar commercial genres (such as science fiction, or “the Western,” or even “serious literature”). Like their central characters, they remain uniquely, supremely, and self-indulgently themselves. As a result, Portis’s life’s work has never been properly appreciated, despite a legion of prominent admirers, from Ed Park and Donna Tartt to Wells Tower. (Jonathan Lethem has called Portis “everybody’s favorite least-known great novelist.”) For while True Grit was an almost perfect combination of imaginative storytelling and commercial success, it set the stage for one of the most remarkable disappearances-in-plain sight of contemporary literature.

The gravity-bound homebodies of Portis’s books sound a lot like their creator, whose known biography is about the sparsest of any major twentieth-century novelist. In fact, most of the corroborated information about him can be found in a slim chronology at the back of the new Library of America volume of his Collected Works, assembled by editor Jay Jennings.

Portis was born in El Dorado, Arkansas, on December 28, 1933, his mother a poet and newspaper columnist, his father a school superintendent. He joined the Marines after high school, then got a journalism degree from the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, and became a reporter. For four years, he worked for the New York Herald Tribune, and in 1963 became bureau chief in London. His friends and colleagues at the time included Lewis Lapham, Jimmy Breslin, Nora Ephron, and Tom Wolfe, who recalled Portis’s sudden departure from the profession in 1964:

Portis quit cold one day; just like that, without a warning. He returned to the United States and moved into a fishing shack in Arkansas. In six months he wrote a beautiful little novel called Norwood. Then he wrote True Grit, which was a best seller. The reviews were terrific…. A fishing shack! In Arkansas! It was too goddamned perfect to be true.

Portis, like one of his own characters, entered the world of employment only long enough to find a way out of it. His first, perhaps least-known novel, Norwood, was a slim, hilarious tale of a young man venturing forth from his hometown of Ralph, Texas, just long enough to collect $70 owed him by an old military buddy. Norwood’s “big adventure” develops as little more than a series of accidental routes taken and encounters with mundanely unconventional comic characters, culminating with a late-night conversation on a bus that leads to Norwood proposing marriage to a girl he has just met. At which point Norwood does what so many of Portis’s characters end up doing—he goes home, bringing his new fiancée with him.

It wasn’t until after his second novel, however, that Portis no longer had to work at all. True Grit seems to have grown from the mightiest fictional materials of Portis’s life: the stories of cataclysmic Civil War and Western rowdyism that he listened to when his father and uncles and grandparents got together.

There are two types of people in Portis: those who walk their roads with a modicum of decency, like Mattie, and those who travel with gangs, cheating and lying (often to one another) for money, such as Chaney and his outlaw honcho, Lucky Ned Pepper. This often means some unlikely characters end up on the side of the good. Rooster, for instance, is a crude man who drinks and kills too much, but what makes him noble in Mattie’s eyes is that he finishes each job he sets out to do. He is also not a liar or a cheat, and possesses a sense of self-irony. When Mattie finds him drunk in his back room at a Chinese grocery store, playing with her father’s too large gun and pointing out a “big long barn rat” raiding a sack of meal, he understands the absurdity of his role:

He leaned forward and spoke at the rat in a low voice, saying, “I have a writ here that says for you to stop eating Chen Lee’s corn meal forthwith. It is a rat writ. It is a writ for a rat and this is lawful service of said writ.”

He fires at the rat, and the store’s owner sits up in his bunk and admonishes him: “Outside is place for shooting.” “I was serving some papers,” Rooster replies. It’s not what Portis’s characters do or accomplish that makes the novels come alive from the first sentence right through to the last—it’s how they speak about what they do, often while doing it, always striving to sound more lucid, rational, and articulate than their crude educations permit, a combination of factors that, in Portis’s hands, flashes with eloquence.

Like Mark Twain, William Saroyan, or even Damon Runyon, Portis was a poet of American vernacular; the oddly rhythmic ways his characters spoke reflected more than the regions that formed them—they marked the deep twists and contradictions of their inner nature. But despite frequent comparisons to Huckleberry Finn, Portis’s Mattie and the eponymous Norwood are not the sort who, on a whim, will “light out for the territory ahead of the rest,” but rather are always looking to return home and settle down to their normally humdrum, routine lives. (There is more of L. Frank Baum’s Dorothy Gale about them than Huck Finn.) If anything, Mattie only wants to bring the wild West back to Arkansas in the embodiment of Cogburn’s casket, which, at True Grit’s conclusion, she buries in the family plot and memorializes with a $65 tombstone.

After the success of True Grit, The Dog of the South—arriving 11 years later in 1979—was a return to form, but a form unrecognizable to anybody who only knew Portis through True Grit. The typical Portis character is not, like Rooster Cogburn, larger than life in a John Wayne–ish sense; they are rather memorable for their idiosyncratic smallness, being no more than average men with modest, useful skills for plotting courses on road maps, or rigging their battered old trucks and cars just well enough to get them another few miles down the road. (There is no novelist who knows more ways to cheaply fix broken cars than Portis, who spent time in his youth as a car mechanic.)

When Dog opens, its protagonist, Ray Midge, has just been abandoned by his wife, Norma, for her previous husband, Guy Dupree, a copy editor at the newspaper where Midge works. Perhaps even more unforgivably, Dupree has taken Ray’s Ford Torino, his “good raincoat and a shotgun.” Until the loss of his wife, Ray lacked any sense of adventure. He daydreamed about earning a teaching degree, and established petty rules around the house. (“Two of my rules did cause a certain amount of friction—my rule against smoking at the table and my rule against record-playing after 9 p.m., by which time I had settled in for a night of reading.”) Unlike his errant wife, Norma, Ray is not an adventurous personality; he regrets showing no support for her enthusiasms:

She wanted to dye her hair. She wanted to change her name to Staci or Pam or April. She wanted to open a shop selling Indian jewelry. It wouldn’t have hurt me to discuss this shop idea with her—big profits are made every day in that silver and turquoise stuff—but I couldn’t be bothered. I had to get on with my reading!

The dastardly Dupree, on the other hand, is too exciting for his own good. He faces trial for making written threats to the president, which he signs with made-up names such as “Night Rider” and “Jo Jo the Dog-Faced Boy.” (“This time it’s curtains for you and your rat family. I know your movements and I have access to your pets too.”) He worries that his incompetent court-appointed lawyer will “stipulate my ass right into a federal pen” and runs off to Mexico. His only mistake is in using Midge’s Texaco card to pay his way. Once the bills start arriving, Midge sets off to bring home what’s his.

It’s another “there and back again” novel, but one in which the “there” turns into an endless journey down bad roads in Dupree’s crappy car, during which Midge encounters all sorts of mesmerizingly wild, verbose characters and even crappier lodgings. Midge qualifies as a good man under Portis’s not very stringent qualifications. He is generous to those in need; and he listens politely to the men and women who come banging through his life. Chief among them is Dr. Reo Symes, a con man seeking a ride to his mother’s missionary outpost in Belize (where she plays the same Heckle and Jeckle cartoons repeatedly and then, once the audience is settled inside her church, bolts all the doors). Symes has spent much of his life running fraudulent mail-order schemes and selling dodgy hearing aids to the elderly, and just summarizing his exploits requires at least one long road trip of listening. As Ray recounts:

I learned that he had been dwelling in the shadows for several years. He had sold hi-lo shag carpet remnants and velvet paintings from the back of a truck in California. He had sold wide shoes by mail, shoes that must have been almost round, at widths up to EEEEEE. He had sold gladiola bulbs and vitamins for men and fat-melting pills and all-purpose hooks and hail-damaged pears. He had picked up small fees counseling veterans on how to fake chest pains so as to gain immediate admission to V.A. hospitals and a free week in bed. He had sold ranchettes in Colorado and unregistered securities in Arkansas.

But throughout this steadily unrolling catalog of iniquity, Ray—like most of Portis’s protagonists—never judges; he only relates. “I once looked into medicine myself,” Ray confesses to the endlessly chatting Symes, who doesn’t pay attention to anybody but himself. “I sent off for some university catalogues.” Portis’s characters know that they can’t be too judgmental—if they were, they wouldn’t have any friends.

If Dog is Portis’s comic tour de force, his next novel, Masters of Atlantis, written with what seems to be painstaking, sentence by sculpted sentence joy over the next six years, is his Magic Mountain. Tracking the progress of the fictional Gnomon Society—whose contentious fellow travelers include French Rosicrucians, Madame Blavatsky, the Druids, and “Aleister Crowley’s grisly gang”—Masters encompasses such a wide vision of benign theosophical idiocy that it feels like a secret kingdom all its own. For while there are virtually no fantasy or supernatural events in any of Portis’s books, his weirdest and most likable characters often enjoy imagining vast metaphysical possibilities. While making their home in the world they know, they often try to imagine a better one.

Masters begins in France in 1917, when Lamar Jimmerson acquires the Codex Pappus from a “dark bowlegged man” looking for a meal. The Codex, the man claims, has been copied from an original book that “had been sealed in an ivory casket in Atlantis many thousands of years ago, and committed to the waves on that terrible day when the rumbling began.” Filled with a perplexing number of triangles, the Codex reportedly established a secret brotherhood that once included Hermes Trismegistus, Pythagoras, and Cagliostro—but ever since those characters disappeared into the transcelestial wonderment, the twentieth century has to accept Jimmerson for any further illuminations. He imperfectly translates the Greek Codex with the help of some tourists at a hotel in Malta, meets other young men seeking wisdom, and embarks on a lifetime of service to hermetical transhistorical forces.

Masters is the most unusual of Portis’s five unusual novels, covering many decades, many lives, and many epiphanies in the life of a religion narrated from the inside out. As Jimmerson ages, the acolytes come and go; and the most inescapable of them, Austin Popper, eventually returns to their temple in Burnette, Indiana, to convince Lamar to make a gubernatorial run. To this end, Popper advises they prepare a campaign biography of the great man, enlisting the help of a hack writer from Indiana named Dub Polton, whose pen names include Jack Fargo (’Neath Pecos Skies), Vince Beaudine (Too Many Gats), Dr. Klaus Ehrhart (Slimming Secrets of the Stars), and the popular juvenile writer, Ethel Decatur Cathcart (Billy and His Magic Socks).

Masters, like Jimmerson’s Codex, is sui generis, even by comparison with Portis’s always unusual work. The Gnomons devote themselves equally to metaphysics and to the pointless disputes and exacerbations of day-to-day operations. (At one point, they enjoy a successful membership drive by reducing the number of triangles in their translation of the Codex.) They thrive, fail, develop, and scupper alliances, and drift apart and together again throughout their intensely private musings about the “meaning” of Atlantis. It’s a book about finding beauty in a world after World War I that must not have seemed very beautiful at all.

It is hard to imagine a greater or more valuable pleasure-per-ounce package than the collected works of Charles Portis, a writer who made the most out of being barely well-known. For once the movie people stopped seeing his cinematic possibilities, Portis could get back to producing his unassuming, always surprising and entertaining books; and once the critics stopped finding easy ways to compare him to the wide horizons of America, he could continue exploring the intimate, absurd spaces he preferred. In one of his rare interviews, he made the self-deprecating remark: “Anything I set out to do degenerates pretty quickly into farce.” But of course nothing about Portis’s fiction ever “degenerates” as it goes along, so much as it gathers a sort of gleeful enthusiasm for the smallest pleasures of human life—good meals; sometimes-dependable friends and partners; neat, warm beds; and unusual conversations.

In one of his last published pieces, “Motel Life, Lower Reaches,” Portis went searching for “that ideal in my head of the cheap and shipshape roadside dormitory,” where he could recuperate at night from his drives between Little Rock and Mexico and back again. (Portis joked that one of the most alluring of the motels should have offered signs out front flashing: NOT QUITE A DUMP … AT DUMP PRICES.) After various adventures in itinerant living, he thinks he finds it at the Desert View in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico (the sort of name that, if it hadn’t existed, Portis would have to invent), which he describes as “a bit small but clean, new, modern, all those things, with a gleaming white bathroom.”

The bed was flat and firm. Over the headboard there were two good reading lamps mounted on pivots. I had air conditioning, cable television. A refrigerator, and a microwave oven. It was a quiet place with few guests, none of sly or rat-like appearance. I could park directly in front of my door.

Clean, simple, and with ample light for reading—the perfect space for a man like Portis, never a total stranger to the people he met, and always ready to take another quick jaunt down the road.