“We were as close as sisters can be,” Mary Cheney has said about her bond with her older sister Liz, now apparently broken after the Cheney family feud over gay marriage. All the media coverage of their falling out brings back memories of my literary encounter with sisterhood Cheney-style. In the early 1990s, during a summer in Paris, I was checking out the booksellers along the Seine when I spotted a paperback called Sisters, with a cover picture of 19th-century ladies in bonnets from the Women’s’s Freedom League, standing behind two dark-haired lovelies. The teaser on the cover read “the novel of a strong and beautiful woman who broke all the rules of the American frontier.” The author's name was Lynne Cheney.

The Lynne Cheney? No way, I thought. Cheney was then the conservative chair of the National Endowment of the Humanities, crusading against political correctness and multiculturalism. I had never heard of this title, published by Signet Canada in 1981. But Sisters was set in Wyoming, where she grew up. It was both a pulpy murder mystery, with cattle barons and homesteaders; and an astoundingly sympathetic treatment of Wyoming women’s culture in 1886. The heroine, Sophie Dymond, is a sophisticated actress and magazine editor from the East who returns to Cheyenne to investigate the death of her sister Helen. As the jacket explains, she seeks answers “in the secret world of frontier wives,” in a time and place where “the relationship between women and men became a kind of guerilla warfare in which women were forced to band together for the strength they needed and at times for the love they wanted.” Sophie finds a letter to Helen from a close woman friend, proposing an elopement, and she watches two women embracing with understanding: they “ had a passionate loving intimacy forever closed to her. How strong it made them. What comfort it gave.”

In her acknowledgments, Cheney thanked “the men and women working to bring to light details of the daily personal lives of nineteenth-century women,” especially the feminist historians Linda Gordon and Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, who had written about birth control and the subculture of 19th-century American female bonding. Although she was no friend of women’s studies in the 1990s, Cheney got a Ph.D. in English in 1970 from the University of Wisconsin and would surely have encountered pioneering feminist scholarship. She had published two other mass-market novels, Executive Privilege (1979), and, with Victor Gold, The Body Politic (1988). And the dedication clicked too: “To my mother and my grandmothers, at rest in the past, and to my daughters, who are running toward the future.” Cheney’s mother had been a deputy sheriff in Casper, Wyoming, and her daughters Liz and Mary were 15 and 12 in 1981.

I brought the book home and shared it with my colleagues on the Executive Council of the Modern Language Association, which was engaged in its own battles with Cheney over her nomination of a poorly-qualified rightwing academic for the National Humanities Council, and rumors that the NEH was vetting grant applications for ideological agendas. Cheney and her deputy made a state visit to a Council meeting; she was about as friendly as the Wicked Witch of the West. It didn’t seem like a good moment to ask her to autograph my copy of Sisters. (I regret that now, because in 2009, according to Wikipedia, a copy autographed by Cheney was selling for $1,500.)

But in September 2000, when Dick Cheney was nominated as Bush’s running mate, I wrote about Lynne Cheney’s fiction in the staid academic weekly, the Chronicle of Higher Education. The New York Times ran a piece about Sisters right after. Cheney told them sweetly that the book had originally sold about 500 copies, and that she hoped “the renewed interest it it will send it flying off the shelves.” Not likely. It was already extremely scarce. By 2004, Patt Morrison at the Los Angeles Times could find only 11 copies in all the public libraries in the U.S. Four of those were in Wyoming. That year, Cheney’s attorney, Robert Barnett, stopped a proposed republication of the novel. Cheney didn’t think it was her best work.

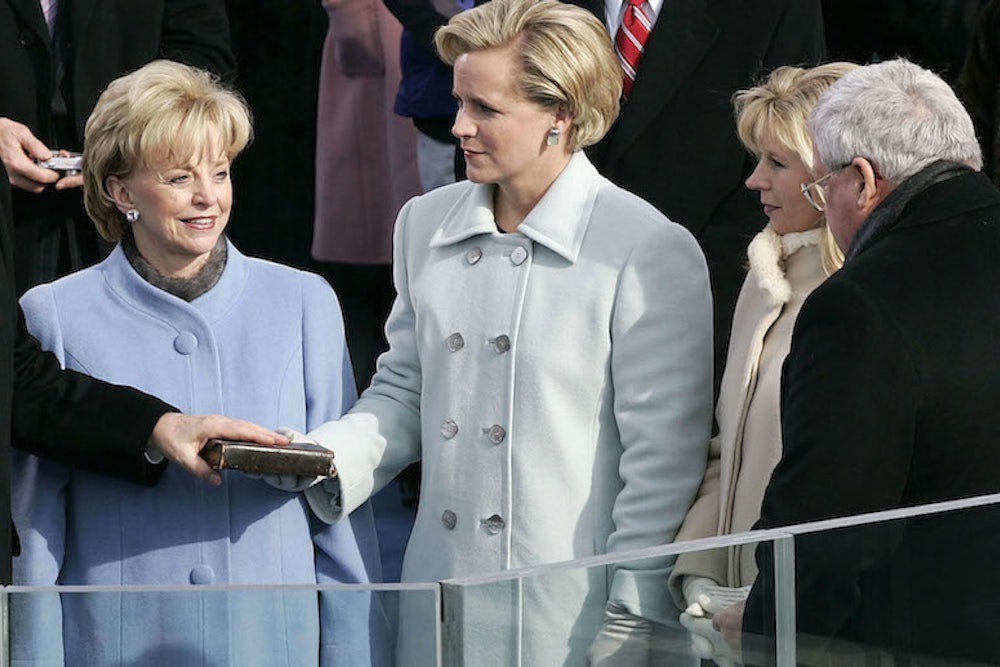

So what about the feud, and the Cheney parents awkwardly and unhappily caught between their daughters? When I wrote about Sisters in 2000, I thought it was ultimately a metaphor for the profound differences between women, and the impossibility of achieving total sisterhood. But Cheney sees empathetic identification as the essence of sisterly behavior. “The hardest thing any human being can do,” a woman in the novel declares, "is fully to acknowledge the actuality of another. To admit, truly admit, that their thoughts, cares, their ardors and aversions, are—or were—as real as our own.” When Sophie understands this idea, she realizes that she and Helen were not so different after all. If Liz and Mary Cheney read Sisters as they were running towards the future, I hope they remembered these lines. If these two professional, Republican, married-with-children twigs on the Cheney family tree can’t get along, who can?

Elaine Showalter is professor emerita of English and American Literature at Princeton University. Her most recent book is A Jury of Her Peers; American Women Writers from Anne Bradsreet to Annie Proulx.