During one of many rousing public demonstrations shown in Laura Poitras’s new documentary, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, a middle-aged activist lays out—in the plain, swift terms made possible, at this historical moment, by sheer grim familiarity—the consequences of her child’s encounter in his teens with the painkiller OxyContin. “I don’t expect the Sacklers to care about my son,” she goes on. “But 400,000 lives? Somebody should care about that.”

Though forceful and affecting, the bereaved mother’s words are also eerily undermined by their context. Poitras’s film—a collaboration with the visual artist Nan Goldin—zooms in on a single life in rich detail. Using archival footage and voice-over, as well as Goldin’s own artwork spanning decades, it tells Goldin’s story from her unhappy suburban childhood to her breakthrough as a photographer in the 1980s to her own addiction and activism.

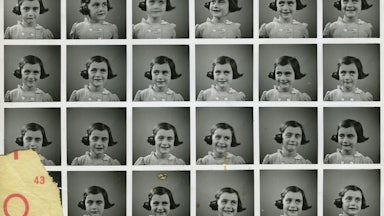

Goldin has always been singularly adept at presenting a vision of her own experiences that emphasizes their broader resonance: In her late teens, she started photographing her friends and crushes among the queer and drag communities of Boston in the 1970s. After moving to New York, she became famous for her highly influential diaristic work in a similar vein. Gorgeously mythologizing yet frank in its depiction of drug use and violence along with many forms of camaraderie, her photographs document a vivid social world, around the Bowery, that would soon all but disappear. Many of her subjects did not survive the 1990s, thanks to the AIDS crisis. In Poitras’s film, we are granted the brief but mesmeric presence of the late artist and writer David Wojnarowicz, and see the young Goldin and her friends in snippets from underground films like Bette Gordon’s Variety.

Goldin documented her own period of intense dependence on OxyContin, originally prescribed to her for a surgery, in the January 2018 issue of Artforum, in a portfolio of images with titles like Self Portrait 1st Time on Oxy, Berlin, 2014; Dope on My Rug, New York, 2016; and Pain/Sackler, Royal College of Art, London, 2017. She included short, sharp, personal testimony, describing her swift progression to an all-consuming addiction, a fentanyl overdose, and a stint in rehab, and she announced her formation of the group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, or PAIN. Her central project since then has targeted the Sackler family, who ran Purdue Pharma, and whose aggressive marketing techniques helped spawn the current opioid epidemic. She eventually persuaded institutions, including the Met, the Louvre, the Tate, and the Guggenheim, to remove the Sackler name from their walls and reject or return the family’s funding.

Goldin’s outsize talents put a certain pressure on Poitras’s established approach as a documentarian: Her previous work—notably My Country, My Country (2006, filmed in Iraq); The Oath (2010, about Guantánamo Bay); and Citizenfour (2014, her Oscar-winning study of Edward Snowden)—embraced activist outrage and courage in the face of vast, powerful enemies and combined it with a curiosity about the experiences of individuals directly affected. The film she has made with Goldin becomes a more surprising, sometimes awkward, mix of genres. Part portrait of the artist, part campaign or exposé, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed seems a special study in the power (and occasionally the limits) of personal narrative flair as a weapon against larger social and political ills.

A family often provides the setting for the earliest collision of the personal and political, where those larger ills first begin to play out in all their florid cruelty. And the film makes clear that, for Goldin, resistance began, like charity, at home. Born in 1953, she grew up in a sedate suburb of Boston with parents who seemed ambivalent about raising children at all and horrified by any flash of autonomy that showed in them. Right away, the viewer is given a clear impression of where and how Goldin must have developed the sensibility expressed in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985), a slideshow and book of photographs of her ’80s New York City milieu—showing the likes of Cookie Mueller and other bohemian friends, lovers, and comrades, gloriously dressed and made up according to a wide range of gender and sexual expression, engaged in bacchanalian splendors. The world of her childhood is by contrast portrayed as steeped in a brand of wretched conformity, dissatisfaction, denial, and displacement that she learned, aged 11, with the culmination of the family’s tragedy, to see as quite literally a matter of life and death.

The film is dedicated to Goldin’s elder sister, Barbara, a spirited and creative person whose romantic interest in other girls alarmed her parents, and who introduced Goldin to the books and music and art that became vital to her and to the necessity of personal rebellion. While Goldin was still small, Barbara began disappearing into a series of institutions, from orphanages to psychiatric hospitals; her medical records are heartrending. In her late teens, she placed her few belongings neatly by the side of some railroad tracks before taking her own life, an event their mother insisted on explaining as accidental. Goldin herself was eventually sent to a series of foster homes, and—having learned that self-definition might not come without a fight—claims to have been thrown out of every last one. She found her own makeshift family group in New York City, where she survived and saved up for photographic equipment through various forms of sex work (sometimes taking the bus into New Jersey, where you could make money stripping without taking everything off), and tended bar at alternative haven Tin Pan Alley.

Goldin at one point attributes her attraction to photography to growing up in an environment where her perception of reality was constantly undermined—she found ways to put her version, her perspective, on the record. That approach is most obvious in the self-portraits she took after being severely beaten by a boyfriend; but by the same token, she gave the subjects of her photographs the opportunity to destroy any they didn’t like. Indeed, her portraits insistently glamorize the people in them, which is partly why their political charge is less legible now than it would have been at the time, as AIDS took hold and the National Endowment for the Arts withdrew funding from artistic work it considered sexually deviant. The impulse to canonize oneself and one’s friends has been thoroughly commodified in the intervening decades.

Goldin herself, of course, has benefited professionally from that commodification—her work appears in the permanent collections of many of the world’s foremost art institutions. What presumably made her an appealing subject for the intrepid Poitras is that during precisely the period of her career when she might be expected to consolidate and enjoy that success, she has instead been experimenting with it as a political tool to confront the opioid epidemic, revisiting some of the tactics used by ACT UP in the ’80s and ’90s.

In 2019, Goldin withdrew her consent for a retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery in London until it had agreed to turn down a million-pound donation from the Sacklers. She brought an artist’s sense of spectacle to her protests, staging die-ins on the floor of the Met’s Temple of Dendur (in a part of the museum then named the Sackler Wing), where her group flung pill bottles into the reflecting pool, and at the Guggenheim, where huge quantities of fake prescription slips doctored with incriminating Sackler quotes were sent fluttering down from the upper loops of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous spiral.

Goldin has used her power and celebrity within the art world to great effect, and PAIN has likewise accomplished its relative success by attacking the Sacklers more as villainous individuals—dogged, callous, and inventive in the pursuit of profit; sluicing their blood money through every gallery and museum that would bear their name—than as gruesome expressions of a much larger and more entrenched set of problems within the U.S. health care system, which is structured such that drug companies have enormous discretion over the testing of their products and enormous leeway to create incentives for doctors to push them on patients.

In one scene, at a Zoom bankruptcy hearing for Purdue, a judge asks members of the Sackler clan to confirm their presence, as people detail the loss of their loved ones to addiction. Making the Sacklers witness these stories is presented as a small but crucial part of the compensation these families can get. Holding the Sacklers to account financially has been a lot trickier to achieve. Goldin’s group has argued that some of the massive profits the family removed from Purdue before declaring it bankrupt should be paid back into funding for needle exchanges and other harm-reduction efforts. Yet only a relatively small amount of money has been extracted from the family so far, and that has come at the cost of legal and civil immunity.

Poitras’s film makes efforts to emphasize the thrillerish personal misdeeds of the Sacklers: She reconstructs accounts by activists and journalists of being followed and intimidated by unidentified men in cars. But these sequences feel unsurprising and underwhelming relative to the facts already on the public record. At the Guggenheim, for instance, Goldin and her colleagues made effective theatrical use of Richard Sackler’s vow to cover the United States in a blizzard of Oxy prescriptions. “If anyone belongs in jail, it’s these people,” Goldin says at one of her group’s meetings. “Until the whole prison system is dismantled, they should be the last to leave.”

Goldin Sheds the light of her personal charisma on problems that are often so heavily stigmatized as to forestall rational discussion of the possible solutions. At a state Assembly hearing about methadone and other long-term treatment, Goldin testifies: “It’s not my road to recovery; it is my recovery.”

Toward the end of the film, we see footage of Goldin’s parents talking to the camera about her late sister and going through some of her things. Asked to read aloud the quotation Barbara had typed on an index card and left in her handbag by the train tracks—about the necessity of living with remorse for one’s mistakes in life—her mother begins to cry. It’s clear that, for Goldin, her sister was the first model of an artist, a brave and vibrant figure who goes her own way even at great cost, and who is capable of affecting her enemies, forcing her perspective on them, many years after she’s gone.

It’s a romantic image of what an artist can do, a child’s image, perhaps. And yet, if there is something a little uncomfortable about the relentless focus of Poitras’s film on Goldin herself, about the grandiosity in its portrayal of her individual heroism, it’s nonetheless striking how rare and notable and moving it feels for someone who has such leverage to make any serious attempt to use it for the collective good.